LONGFORM

In search of

Japan’s lost wolves

Zoological mystery

A stuffed specimen of the Japanese wolf at the University of Tokyo's Faculty of Agriculture. | COURTESY OF THE FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE, UNIVERSITY OF TOKYO

The true identity of the Japanese wolf has attracted much research, and yet the elusive carnivore remains one of Japan's greatest zoological mysteries.

ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Staff writer

In the summer of 1823, Philipp Franz von Siebold arrived in Japan to work as a resident doctor at Dejima, an artificial island in the port of Nagasaki that was a Dutch trading post until the mid-19th century.

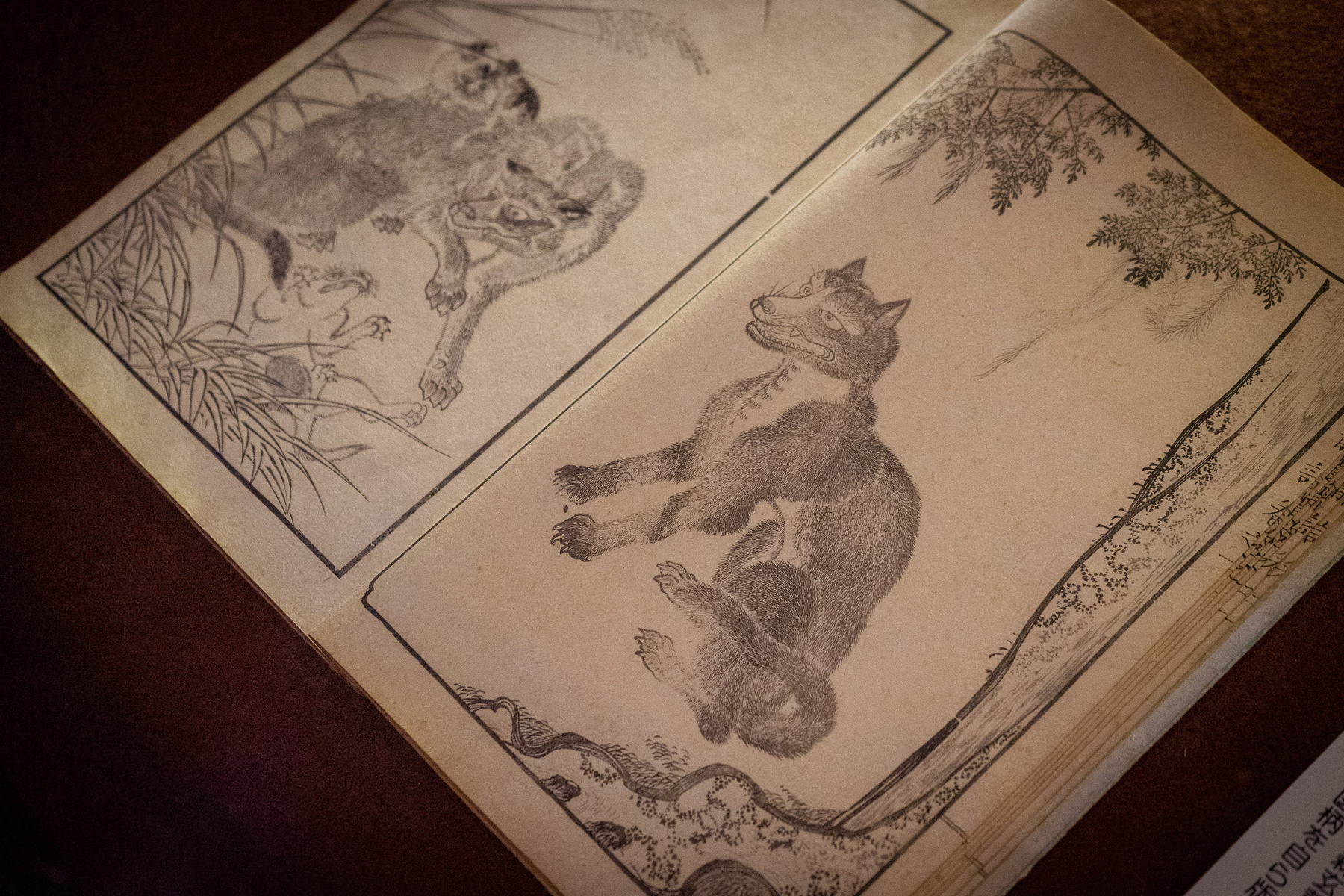

A prolific collector of animals, plants, artworks and maps, the German physician and botanist introduced the latest Western medicine to Japanese students and engaged himself in the study of the nation’s fauna and flora. His research would eventually lead to the publication of the five-volume “Fauna Japonica,” the first book written in a European language about animal life on the archipelago. The title helped establish the basis for zoology in Japan.

Records indicate that in 1826, en route to Edo, the capital of the Tokugawa shogunate in what is present-day Tokyo, Siebold stopped by Tennoji temple in Osaka. There, he purchased two live canines, describing one as an ōkame (ōkami), or wolf, and the other a jamainu (yamainu), or mountain dog. Whoever sold him the animals, one presumes, offered them as distinct beasts known by different names.

Siebold accumulated tens of thousands of specimens and artefacts during his initial six-year stint in Japan, and is said to have kept the wolf and mountain dog in Dejima before having their specimens sent to the Netherlands. But exactly how they made their way across the sea — either dead or alive — remains a somewhat murky story, perhaps due to a major scandal that erupted in 1828 that would lead to Siebold’s banishment from the country.

An Edo Period painting of Philipp Franz von Siebold by Kawahara Keiga | PUBLIC DOMAIN

In what became known as the Siebold Incident, the Bavaria-born naturalist was accused of spying — specifically, obtaining and trying to ship out several detailed maps of Japan, an act that was strictly forbidden under the nation’s isolationist policy. Siebold was subsequently expelled from the country, and left the shores of Japan in late 1829 with his extensive collection of animals, plants and books.

Today, nearly two centuries later, Siebold’s wolf and mountain dog specimens, along with another full skeleton of a dog-like animal, are stored at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands. They are collectively considered the type specimen, or a specimen originally used to name a species or subspecies, of the Japanese wolf — an animal that supposedly went extinct in 1905.

Once the apex predator ruling the forests and mountains of the islands of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, the carnivore saw its population rapidly decline in the late 19th century as the country opened its ports to the outside world and embraced industrialization.

Although the beast was venerated for centuries in Japan as a divine messenger and protector of farmland, much of its ecology and taxonomy have remained shrouded in secrecy. Contributing factors include a limited number of extant specimens, its tendency to avoid humans and the confusion over the true identity of the animals Siebold bought during his stay in Japan, which some describe as one of the greatest mysteries in the history of Japanese zoology.

Modern technology and research into wolf myths and folk legends, however, are helping us better understand this rare creature and how the animal was perceived in premodern Japan.

Surviving specimens

At the northeastern corner of Tokyo’s Ueno Park is the National Museum of Nature and Science. On the third floor of the museum’s Global Gallery is a stuffed specimen of the Japanese wolf — one of four mounted specimens of the creature left in the world.

It’s much smaller than one might expect, with a shoulder height of around 46.5 centimeters — roughly the size of a Shikoku, a Japanese breed of dog. It’s a male specimen sourced from Iwashiro, Fukushima Prefecture. It has brown fur, pointed ears and a short, stubby tail. It’s not intimidating in the least. Rather, it’s beady black eyes and soft features are quite disarming.

I’ve visited the museum on many occasions to examine the specimen but can never overcome the sense of disconnect between the small canine behind the glass partition and the revered beast that appears in Japanese mythology and folklore. Closer to my image, perhaps, are those specimens stored at the University of Tokyo’s Faculty of Agriculture and Wakayama University’s Faculty of Education.

The former sits in a glass case inside the entrance of the dean’s office. It’s slightly larger than the specimen at the National Museum of Nature and Science, with a light, yellowish winter coat and a sharp muzzle enhanced by protruding fangs. The animal was captured in 1881 in Iwate Prefecture, according to the staff member who guided me, and the skull is intact, unlike the specimen at the national science museum, whose full skeleton is stored separately.

In terms of size among the stuffed specimens, the one in Wakayama is the largest. It was likely captured in Nara Prefecture in 1904 or 1905, and it has a shoulder height of 62 centimeters. Based on such measurements, the average shoulder height of the Japanese wolf is considered to be around 50-55 centimeters. That’s substantially smaller than other subspecies of gray wolf — including the Hokkaido wolf, which supposedly went extinct in 1896 — making the Japanese wolf one of the smallest wolves in the world.

This baffling physical characteristic is but one of the lingering puzzles surrounding the beast, further complicated by Siebold’s specimens. The latter consists of three sets of skulls (each categorized as “a,” “b” and “c”), a full skeleton (coupled with “a”) and the fourth remaining taxidermied pelt (coupled with “c”).

Taxonomists, who group organisms into categories, have typically relied on morphological characteristics, especially skull shape, when identifying the Japanese wolf from dogs and other animals. When conducting analysis, they have often referred to Siebold’s type specimen. The late zoologist Yoshinori Imaizumi, for example, relied on them when examining images of a wolf-like creature that were taken in 1996 by Hiroshi Yagi, a man who has dedicated much of his life in search of the Japanese wolf.

The problem is that these three sets of specimens all appear to belong to different animals.

While Siebold labeled and clearly differentiated the wolf and mountain dog, Coenraad Jacob Temminck, a Dutch zoologist who was the director of the National Museum of Natural History in Leiden at the time, lumped them together. In 1838, he conjointly named them Canis hodophilax, derived from the Greek words meaning “guardian of the path,” a reference to Japanese folklore portraying the beast as a protector of travelers.

The scientific name also indicated that the animal was considered to be an independent species — another source of ongoing debate — although it is generally understood now to be a subspecies of gray wolf and now includes the latin “lupus,” or wolf, in its title: Canis lupus hodophilax. “Canis” is a genus that includes dog-like carnivores such as wolves, the domestic dog, coyotes and jackals.

So what is this creature? Were there two distinct animals present in Japan called the ōkami and yamainu? Or are they one and the same?

Confounding the issue is how the terms were often used interchangeably in premodern Japan along with other variations. The categories of canine were diverse and dependent on the regional, religious and social contexts, and it wasn’t until the early 20th century that the creature was taxonomically classified as nihon ōkami, or Japanese wolf.

All of these points may sound very technical and arcane. However, they are important details to help facilitate understanding of what exactly the animal is. As Steven van der Mije, program manager at the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, says, in terms of Siebold’s specimens “the taxonomic status is at best contested indeed.”

“Research is still going on to establish whether this is a species, a hybrid or just some feral dog,” he says.

A pelt of a Japanese wolf stored at a museum adjacent to Mitsumine Shrine in Chichibu, Saitama Prefecture | OSCAR BOYD

Modern science

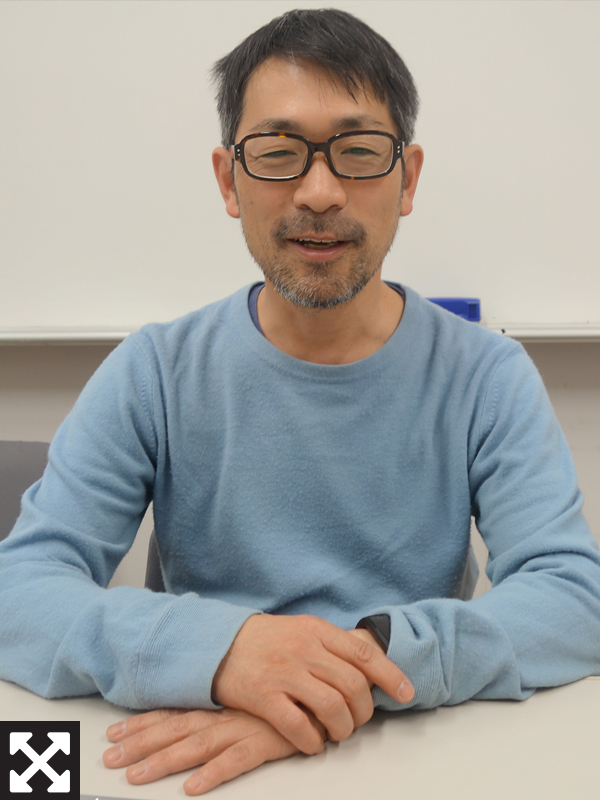

DNA analysis is shedding some light on the true nature of the beast. One of the leading researchers in the field is Naotaka Ishiguro of Gifu University, who has been working to determine the Japanese wolf’s origins and whether Siebold’s specimens belong to the extinct animal.

To date, Ishiguro has examined more than 30 Japanese wolf specimens including skulls, fangs and pelts stored in museums and personal collections. In 2019, for example, he concluded that a canine skull preserved by the board of education of the town of Oyodo in Nara Prefecture belonged to a Japanese wolf. Town officials were relatively confident that the specimen came from the supposedly extinct animal based on the skull’s characteristics, but Ishiguro’s DNA analysis provided a scientific seal of authenticity.

“There are, of course, other instances where the animal I examine turns out to be something else,” he says.

Based on his studies, Ishiguro believes the Japanese wolf likely colonized Japan in the late Pleistocene Era (25,000 to 125,000 years ago) via what is now the Korean Peninsula when the Japanese archipelago was still connected to the Asian continent. In contrast, the Hokkaido wolf, also known as the Ezo wolf, was likely introduced much more recently — from around 14,000 years ago — via a land bridge with Sakhalin Island. Research suggests that at least several thousand wolves once inhabited the Japanese archipelago.

Due to its smaller size compared to the continental gray wolf and some distinguishing skeletal characteristics, the Japanese wolf is sometimes treated as an independent species. In a 1970 article written by Imaizumi, for example, the mammalogist says “hodophilax may not be a subspecies of lupus,” at least according to most modern authors, “but a distinct species well differentiated from any other forms of the genus.”

Ishiguro doesn’t agree with this hypothesis, although he says the Japanese wolf is phylogenetically distinct from other gray wolf populations, suggesting a long period of isolation.

“The Japanese wolf is far older compared with the Hokkaido wolf, which is genetically identical to the gray wolves of North America,” Ishiguro says.

In fact, a recent study published in the journal iScience raises the possibility that the Japanese wolf was closely related to a lineage of Siberian wolves that were previously believed to have disappeared in the late Pleistocene.

Most ancient wolves went extinct when the ice sheets that covered the northern hemisphere began to melt more than 20,000 years ago, killing off large mammals such as the mammoth, which wolves hunted.

Jonas Niemann, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Copenhagen, along with colleagues, analyzed the genome of a Japanese wolf pelt provided by the Natural History Museum in London. Sequencing the nuclear genome of the animal that was shot in the wild in the Chichibu region in the 19th century, they discovered that in contrast to all other modern wolf populations, Pleistocene wolves contributed substantially to the Japanese wolf genome.

“Nowadays only some Arctic dogs carry variants of this Siberian Pleistocene wolf population, so the discovery that this lineage did not go extinct during the Pleistocene and survived in Japan until about 100 years ago was very surprising,” Niemann says.

The skull of a Japanese wolf displayed at the Susono Municipal Mount Fuji Museum in Shizuoka Prefecture | THOMAS DELSOL / HANS LUCAS

There are many unsolved mysteries surrounding the Japanese wolf that draw researchers, including its ancient origins, small size, rapid extinction in the late 19th to early 20th centuries and the purported posthumous sightings that continue to this day.

The confusion over Siebold’s type specimen is among them, although Ishiguro believes he may have found the answer to this particular riddle.

Analyzing bone powder samples from the nasal cavities of the three skulls provided by the Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Ishiguro has determined that skull “a” belongs to a dog. Skull “b,” both morphologically and genetically, belongs to the Japanese wolf. And skull “c,” the specimen Siebold labeled as yamainu, genetically matches the Japanese wolf. However, it’s skull shape has obvious inconsistencies to other Japanese wolf specimens that leaves a question mark.

“You have to understand that these results are based on mitochondrial DNA sequencing that traces the matrilineal ancestry of an animal,” Ishiguro says. A mitochondrial DNA test traces an organism’s mother-line ancestry using DNA in the mitochondria. That indicates that the mother of specimen “c” — the yamainu — was a Japanese wolf.

In order to identify both of its parents, nuclear DNA analysis is necessary, a costly and time-consuming process that Ishiguro and co-researcher Shuichi Matsumura are working on.

“From results obtained so far, it seems specimen “c” belongs to a hybrid, although we need to conduct further analysis to find more details,” he says, adding that there is a high possibility that the animal was a mix between a wolf and a dog.

Based on Siebold’s specimens, there have been theories in the past suggesting that two different animals — the Japanese wolf and yamainu — once existed in Japan. Ishiguro denies that possibility.

“What I can say is that the yamainu is not a distinct canine,” he says. “If it was, it would have shown up in its DNA.”

A view of the Okuchichibu mountains. The area has been home to numerous shrines deifying wolves. | OSCAR BOYD

Genetic identity

Interestingly, there are Japanese dog breeds such as the Shiba and Akita that are considered among the closest genetic relatives to wolves, and still exhibit wolf-like behavior during hunting expeditions.

The oldest dogs in Japan are believed to have arrived during the prehistoric Jomon Period (10,000 B.C. to 200 B.C.), according to Takefumi Kikusui, professor at Azabu University’s School of Veterinary Medicine. For example, bones of dogs given a burial, unearthed from the Kamikuroiwa Rock Shelter site in Ehime Prefecture, date back to 7,300 years, indicating that dogs and people were living together back then.

During the Yayoi Period (250 B.C. to 200 A.D.), farmers from the Korean Peninsula brought with them the Yayoi dog. The newcomers became dominant, spreading throughout the country and pushing the hunter-gatherers and their hounds left over from the Jomon Period to the northern and southern ends of the archipelago. Modern Japanese dogs, Kikusui says, can be traced back to those early Jomon and Yayoi dogs and their hybrids.

The domestic dog is divided into hundreds of island-like populations called breeds. Heidi G. Parker, a researcher at the National Human Genome Research Institute in the United States, examined genomic data from 1,346 dogs representing 161 breeds in a study published in Cell Reports in 2017. In a pie chart featured in the article, the Akita and Shiba are among the 10 breeds listed as genetically closest to wolves, alongside the Siberian husky, Tibetan Mastiff and Greenland sled dog.

Kikusui says research has shown that dogs and wolves are both subspecies that diverged from a common extinct wolf ancestor. The tamest of the wolves may have approached humans and began co-existing and, over generations, evolved into dogs.

“My work focuses on studying the DNA of Japanese dog breeds and finding when this interaction began, and when the wolf and dog separated,” Kikusui says.

And while research by Ishiguro, among others, suggests Japanese wolves are unlikely to have been domesticated into Japanese dogs, Kikusui believes it is possible they crossbred.

“Dogs were often let loose in the mountains, which was the habitat of the Japanese wolf,” he says. “There must have been instances where they mated, producing hybrid offspring that may have been described as yamainu.”

Studies by Niemann, among others, support this theory.

“The specimen we analyzed had Japanese dog ancestry and our results suggest that at least some Japanese dogs also carry Japanese wolf variants today,” Niemann says. “It would be very interesting to sequence the genomes of historical Japanese dogs to investigate how long Japanese wolves have hybridized with dogs.”

Once worshipped as deities offering farmers protection against crop raiders such as wild boar and deer, wolves were hunted down during the late Edo Period (1603-1868) and Meiji Era (1868-1912) because they preyed on livestock, and occasionally hurt and killed humans.

Kikusui, an animal behavior expert, says wolves are extremely wary of people and aren’t aggressive toward them by nature. He suspects that, in many instances, humans may have mistaken wild dogs and even wolf-dog hybrids for wolves, a mix-up that could have inadvertently played a hand in the Japanese wolf’s demise.

While the Japanese wolf is known to have dwelled deep in the mountains, much of its ecology remains unknown. Perhaps that is one reason there have been persistent reports of sightings of wolf-like creatures to this day. Kikusui, for one, is inclined to deny that possibility, citing how the animal is known to have moved in tightly knit packs of as few as two to as many as 10 wolves. To guard against incest, he says, there would need to be a minimum of 50 to 100 wolves, numbers that would have guaranteed many more sightings.

The rich trove of wolf folklore handed down for generations in rural communities, however, offers us clues on how humans interacted with the obscure animal.

Kikusui says some of these legends, including “okuri-ōkami,” or the tales of the “escorting wolf” that followed travelers on mountain trails and protected them during their journey, are likely based on real behaviors.

“The Japanese wolf or yamainu is known to have possessed that particular trait of stalking those who enter its territory,” he says.

A painting depicting shinken ubutate, or the birth of the “divine dog,” stored at Mitsumine Shrine's museum in Chichibu, Saitama Prefecture. | OSCAR BOYD

Canine deities

There are numerous variations to the story of the escorting wolf, from those that portray the animal as guardians of travelers to those that depict the beast attacking humans who tripped and fell, or lacked respect.

Akiko Hishikawa, a researcher at Aichi University and the author of “The Folklore of Wolves: The History of Human-Animal Relationships,” has collected 149 similar tales from across Japan. Many involve the targeted humans resorting to various rituals both during the ordeal and after they reach their destinations to repel or thank the wolf.

“There are regional characteristics to these tales. In the Kii Peninsula, for example, there are many okuri ōkami episodes featuring humans giving wolves salt,” Hishikawa says. There are even stories of wolves visiting households to drink urine saved as fertilizer, she adds. While the canine may have been trying to extract essential mineral nutrients from the secretion, the strange behavior contributed to the myth that wolves were fond of salt and salty water.

Here’s an anecdote collected by Hishikawa in 1996 from a man in his 70s, a resident of Higashiyoshino village in Nara Prefecture where the carcass of the supposedly last wolf was bought by American explorer Malcolm Playfair Anderson: “We’re here in the mountains. It’s cold, and there wasn’t any electricity back then like there is now, so folks would take lanterns or go without any light when heading back home. Then a wolf may follow you. Wolves seem to be fond of salt. Salt. And urine. If you’re a man, you may stop to take a leak. Then, from what I’ve heard, the wolf would lick that up. And it would follow you all the way back home. And once you realize you’ve been stalked, you’d go inside, grab a pinch of salt and sprinkle it by the gates. It would lick that clean and, satisfied, return to its domain. I hear that’s what people did back in the day.”

Hishikawa says the phenomenon is unheard of among folklore tied to other wild animals in Japan, and could reflect how wolves were deified on the archipelago. Salt was of high value for humans, especially those living in the mountains, and the act of giving such precious supplies to a beast could mean the canine was considered to be of a different caliber among its fellow animals.

Based upon a tale she heard in 1996 from a 77-year-old resident of the village of Higashiyoshino, Hishikawa surmises that “people may have been drawn to the solitude and nobility characterized by wolves.

“I’ve talked to someone who claims to have actually seen a wolf, who said its powerful presence was incomparable to that of a dog,” Hishikawa says.

This man reportedly said he encountered a wolf only a couple of meters away from him while pruning in a forest in 1991.

“I thought it would bite off my hand or leg. So I held up my axe and kept raising my voice,” he is quoted as saying in Hishikawa’s book. This was nearly a century after the Japanese wolf was thought to have gone extinct. “There are folks who question why I thought it was a wolf rather than a dog, but I own seven dogs and I used to be a hunter. I wouldn’t make that mistake.”

Mystical talisman

That sense of fear and awe toward the wolf may have helped spawn the belief that it possesses mystical powers to dispel misfortunes.

When Japan was ravaged by a series of cholera epidemics in the 19th century, for example, pilgrims flocked to Mitsumine Shrine in Chichibu, arguably the mecca of Japan’s wolf worship. Fear of the deadly disease and widespread paranoia led the masses to believe in rumors that the sickness was being transmitted by malicious foreign beasts of Western origin — often depicted as foxes — entering the archipelago and possessing its people.

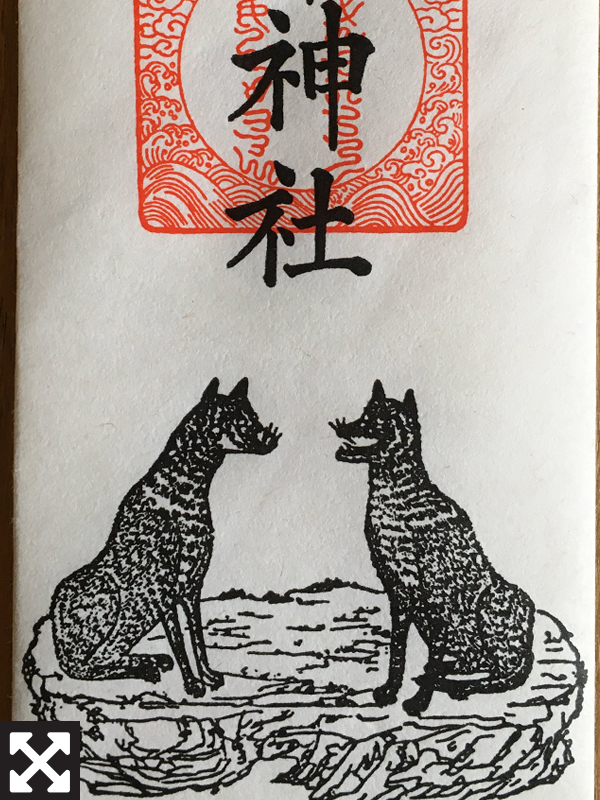

The shrine’s official records indicate that by Aug. 24, 1858 — during a summer of a massive cholera outbreak — 10,000 ofuda paper talismans featuring illustrations of wolves were issued to worshippers traveling to the mountaintop shrine from afar. They sought the supernatural powers of the oinusama, or the divine wolves considered the gods’ messengers, to repel the evil foxes.

Situated around 1,100 meters up the northwestern slope of Mount Myohogatake, the shrine has been home to shugendō, an old ascetic religion combining aspects of mountain worship with Shintoism and esoteric Buddhism. Numerous stone wolf statues dot the premises, silently watching over the parishioners who visit to pay their respects.

Legend has it that Yamato Takeru, a warrior hero from the province of Yamato, founded the shrine. On his way north on a mission to subdue troublesome tribes of non-Yamato affiliation, he became lost in a mist in what is now Okuchichibu. A large white wolf appeared from the mist and guided the warrior to the trail and safety.

Yukiaki Chishima, a senior priest at the shrine, explains that the custom of distributing the wolf ofuda originated in the 18th century.

“As the story goes, a respected monk by the name of Nikko Hoin was praying at his retreat on the night of Sept. 13, 1727, when he noticed the grounds of the institution brimming with wolves,” Chishima says. “Sensing a revelation, he drew pictures of the beasts and distributed them among worshippers as protection against fire and pests such as wild boar and deer.”

The concept caught on, and soon pilgrims began traveling to Mitsumine to acquire the talismans in a tradition that continues to this day called gokenzoku haishaku, or borrowing the gods’ messengers. Confraternities called Mitsumine-ko were formed. Their representatives would make annual visits to the shrine and bring back the talismans to their respective communities. Chishima says there were around 3,000 of these groups in their heyday, although the figure has now fallen to around 500.

The practice of issuing sacred talismans has been shared with more than a dozen wolf-worshipping shrines dotting the Chichibu region, with each offering its original wolf talisman. I’ve collected several of them, each featuring a distinct design.

Mitsumine Shrine’s talisman, for example, shows a pair of wolves facing each other, one with its mouth open (symbolizing “a,” or the sound of an open mouth) and the other with its mouth closed (symbolizing “un,” or the sound of a closed mouth). Together, “a-un” is a Buddhist mantra representing the beginning and the end of all things. This reflects how, before the 1868 Meiji Restoration when Shinto was separated from Buddhism and declared the official religion of Japan, Mitsumine was a Buddhist temple.

Perhaps of special note among Mitsumine’s numerous rituals involving the wolf-god is the practice of shinken ubutate, or celebrating the birth of the divine dog. Chishima, whose forefathers were among the 36 households that originally settled Mitsumine and whose family has served the shrine for generations, knows of ancestors who have partaken in the event.

“According to lore, wolves announced the birth of a newborn by howls that could only be heard by an honest person. My ancestors are said to have heard such howls coming from Mount Wanakura, over yonder,” Chishima says, pointing to the 2,036-meter peak southwest of Mount Myohogatake.

“They reported the phenomenon to Mitsumine, and red rice and sake were prepared and delivered to the site of the howl to celebrate the birth of another messenger for the gods. Records indicate around 30 such observances taking place, the most recent in 1882.”

While that ritual is no longer practiced, on the 19th of every month priests at the shrine continue to perform what they call otakiage, in which they dedicate red rice and sake to the wolf-gods.

Adjacent to the shrine is a museum Chishima manages that features items pertaining to the history of Mitsumine, including information on wolves and paper talismans. At the entrance are enlarged prints of the Chichibu yaken, the wolf-like animal Hiroshi Yagi photographed in 1996. In fact, Yagi is a visiting researcher at the museum, and has helped acquire some of its exhibits, including a wolf pelt and netsuke (miniature sculptures) that incorporate wolf fangs.

I ask Chishima, 67, whether he has ever seen a Japanese wolf in his lifetime.

“Unfortunately not, although they’ve appeared in my dreams,” he says.

“Look at those mountains,” he says, waving his hands over the panoramic views of the peaks seen through the windows of the museum. “The native forests have been replaced by secondary forests. If wolves are still alive, I wonder where they would live.”

That’s a good question.

Japan’s forests cover approximately 25 million hectares, accounting for two-thirds of the nation’s total area. But around 40% has been artificially replanted with fast-growing conifers, a result of a government-led project to destroy native forests to procure lumber to feed demands for energy and housing.

The controversial policy has left a lasting impact on the nation’s woodlands, which were once the Japanese wolf’s natural habitat, an issue I will explore in the next installment of this series.

Chishima remembers how the forests he saw growing up were razed during the nation’s postwar economic boom, forever changing the face of the mountains of Chichibu. Where, indeed, would the wolves live today?