ILLUSTRATION BY SHIN_KUMASHIGE

The attraction of an unsolved mystery, on the run in the forests of Japan, resonates in many ways. In this final installment, we look at the legacy of this venerated beast.

ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Staff writer

In 18th-century France, a diabolic carnivore terrorized the old southern province of Gevaudan, killing more than 80 men, women and children and triggering mass hysteria.

The attacks lasted between 1764 and 1767 and coincided with an economic slump the nation was experiencing on the heels of the Seven Years’ War, which lost France many of its colonies and burdened the country with heavy debts.

Breathless coverage by newspapers and widespread rumors of the Beast of Gevaudan, as the thing was called, elevated the creature to mythical proportions and gave poor rural peasants a common enemy to rally around.

Historians and academics tend to blame one or more wolves or wolf-dog hybrids, with some arguing that the beast was actually an escaped lion. Following several rounds of military intervention, wolves were hunted down and the attacks subsided.

The creature, however, has lived on as source material for literature, films and television programs — illustrating how the predatory canine continues to stimulate our imagination, serving as an important motif portrayed both favorably and unfavorably depending on regional and cultural contexts.

Thomas Delsol, a photojournalist based in southern France, grew up listening to the stories of the Beast of Gevaudan and reading classic fairy tales such as “Little Red Riding Hood” and “The Three Little Pigs,” which feature the Big Bad Wolf, the archetypal deceitful, ravaging beast.

Naturally, he was predisposed to view wolves as villainous, harmful creatures that need to be exterminated, exactly as France had done: Sustained persecution of wolves eradicated them from the nation by the 1930s.

In the 1990s, however, the wolf population reemerged, spreading across the Alps from Italy. It grew rapidly, and now counts around 580 adults, much to the dismay of livestock owners who complain of increased attacks on their flocks.

“For French children, wolves are like devils. They have to learn to protect themselves from these beasts,” says Delsol. “Where I live, wolves are part of our daily lives. We know they’re around the villages and we sometimes find animal remains when we go for a walk.”

So it came as a surprise when the Frenchman learned about the Japanese wolf, an animal that supposedly went extinct more than a century ago. After some research into Japanese mythology and folklore, he realized that unlike its European counterparts, Japan’s versions were often the objects of worship rather than contempt.

They were deified in many shrines as messengers of the gods, protecting farmers from pests and households from fire and theft. Intrigued by the differences in the cultural and religious perceptions toward wolves and by reports of modern-day sightings of wolf-like animals, Delsol decided to visit Japan to research the phenomenon.

I met Delsol in Tokyo in late 2019, shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic led to quarantines and travel restrictions. Together we visited Chichibu, a mountainous region in neighboring Saitama Prefecture considered one of the centers of the nation’s wolf worship.

Little did we know that in a matter of months the outbreak would turn into a health crisis bringing panic comparable to the terror wrought by the Beast of Gevaudan — but on a global scale.

Inspirational symbol

The contrasting reputations of the animal in Japan and Europe could be explained by the archipelago’s predominantly agricultural history of reliance on rice and other crops as pillars of its economy, says Peter Ehret, a German social scientist residing in Granada, Spain, and a researcher in cryptozoology, the study of animals whose existence or survival is disputed or unsubstantiated.

“Consequently, Japan had more problems with herbivores and omnivores like deer and wild boar because of the damage they inflicted on crops,” he says. “That meant people had favorable opinions about the animal that hunted down those species.”

Wolves have long been a source of inspiration and symbol in literature and art, mythology and religion. They appear prominently in Native American folklore as sources of power and courage, for example, admired for their superb hunting skills and fierce dedication to the pack.

In Europe, the wolf was vilified long before Christianization, Ehret says. The foundational myth of the Roman Empire, for example, tells the story of the founding fathers Romulus and Remus, sons of Mars, being raised by a she-wolf known as Lupa.

“The Latin word ‘lupa’ can mean ‘she-wolf’ and ‘prostitute,’” he says, “which may tell us about the reputation of the wolf.

“In Norse mythology, wolves also had an important role,” he continues, describing the Fenrisulfr or Fenrir, a monstrous, malevolent wolf considered to be too dangerous for the gods.

“The gods decide to bind him down but the beast bites off all the chains and kills the god Odin during the events of Ragnarok,” he says, referring to the final destruction of all things in which many gods die and the world is submerged in water.

In ancient Greek mythology, the goddess Hekate is often portrayed in company with wolves, while Lycaon, the king of Arcadia, is transformed into a wolf by Zeus after trying to trick the king of the gods into eating the flesh of his own son. Lycaon’s tale is considered the origin story of werewolves, which became a widespread belief in medieval Europe.

“The werewolf mythos in Europe changed during the course of its history,” Ehret says. In the Middle Ages, anyone desiring to be a werewolf “had to have a pact with the devil, a transformation involving rituals such as wearing a belt made of wolfskin. In the early modern period werewolves and witches were subject to witch trials and often executed by burning.”

While werewolves were closely linked with witchcraft and sorcery in nations such as France and Germany, the dark arts were associated with vampires in Central and Eastern European nations.

The explicitly negative, or even diabolic, image of the wolf in medieval and early modern times can be explained by the predator’s frequent attacks on livestock, especially given the fact that the Middle Ages in Europe were characterized by extreme social inequalities.

“Imagine a wolf pack killing a herd of sheep — it meant economic disaster for the community.”

Perhaps that makes the case of the Japanese wolf all the more intriguing. Rather than being an embodiment of the devil, the animal was considered to possess powers to dispel evil.

Spiritual presence

Lycanthropy, the supernatural transformation of a person into a wolf, does not feature in traditional Japanese folklore. Instead, skulls of wolves were often used to exorcise fox spirits that had possessed people — a widely known phenomenon known as kitsunetsuki.

The Inoue household in Chichibu, for example, has been “preserving” the skull of a Japanese wolf for generations. When a neighbor was acting strangely or suffering from a high fever and thus was believed to be possessed by a fox, family members of the victim would come to borrow the skull and hide it in their home unbeknownst to the patient. The spiritual presence of the apex predator would scare the malicious fox away and free the bewitched, according to lore.

Eventually, those who came to borrow the wolf skull began scraping the bone to collect powder that could be infused in boiling water and served to the sick, a process that was believed to increase the ritual’s potency. When finished, the grated area of the skull was painted with black ink and returned. The custom continued up until 1965 or so, according to the book “Chichibu no Densetsu” (“Legends of Chichibu”), edited by the educational board of the city of Chichibu. Repeated scraping had seen the skull shrink considerably. The Inoues placed it in a glass case and ceased to lend it out.

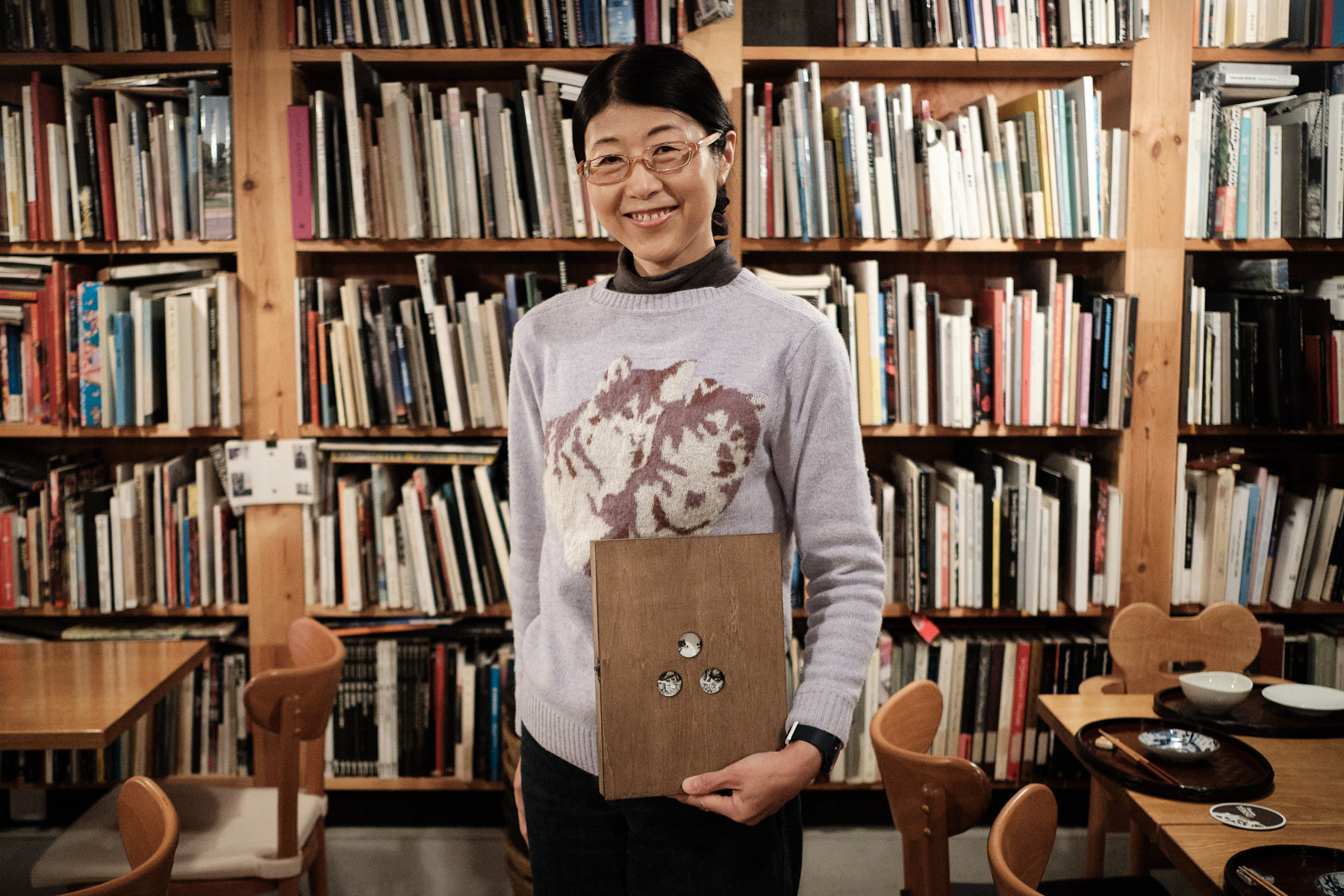

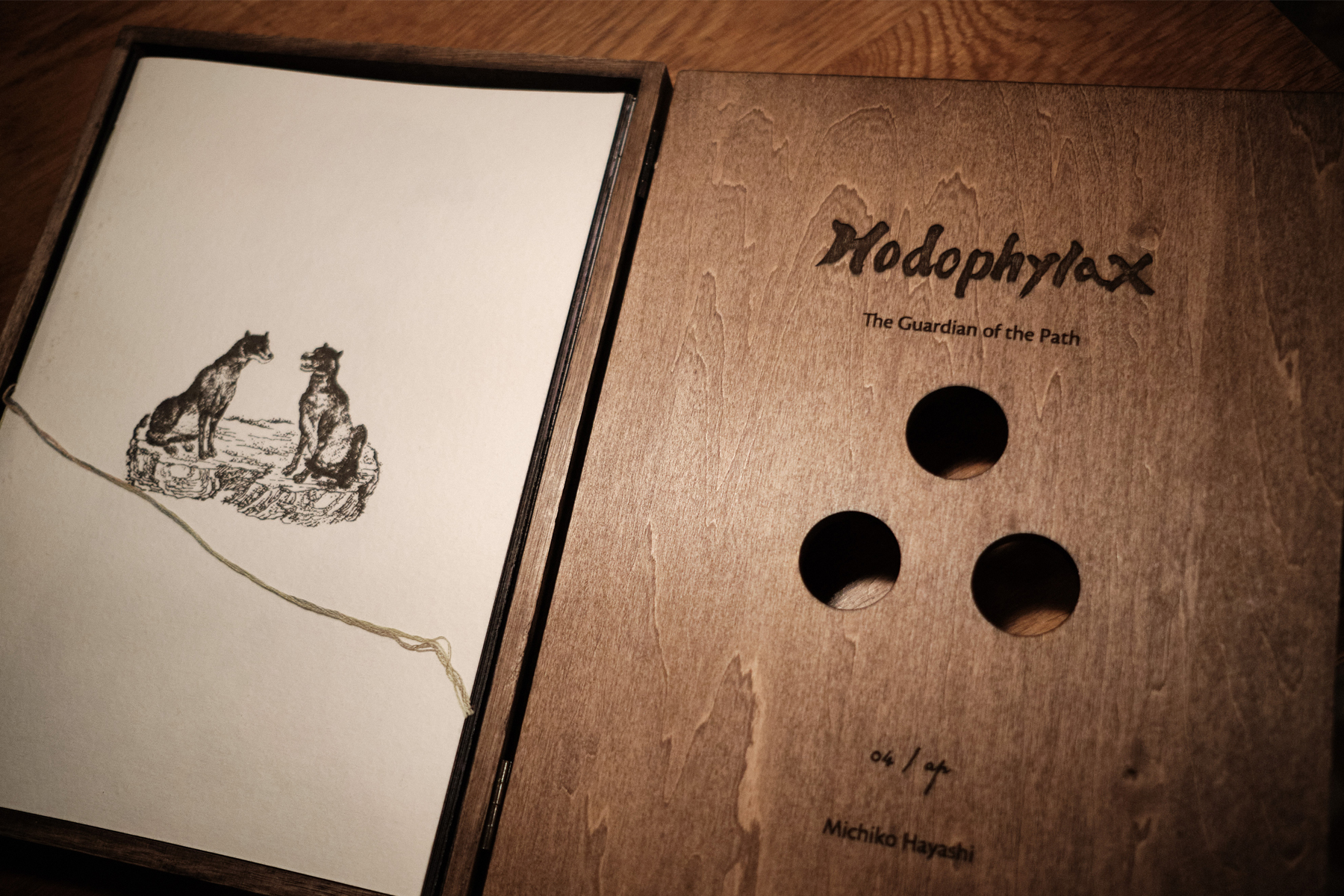

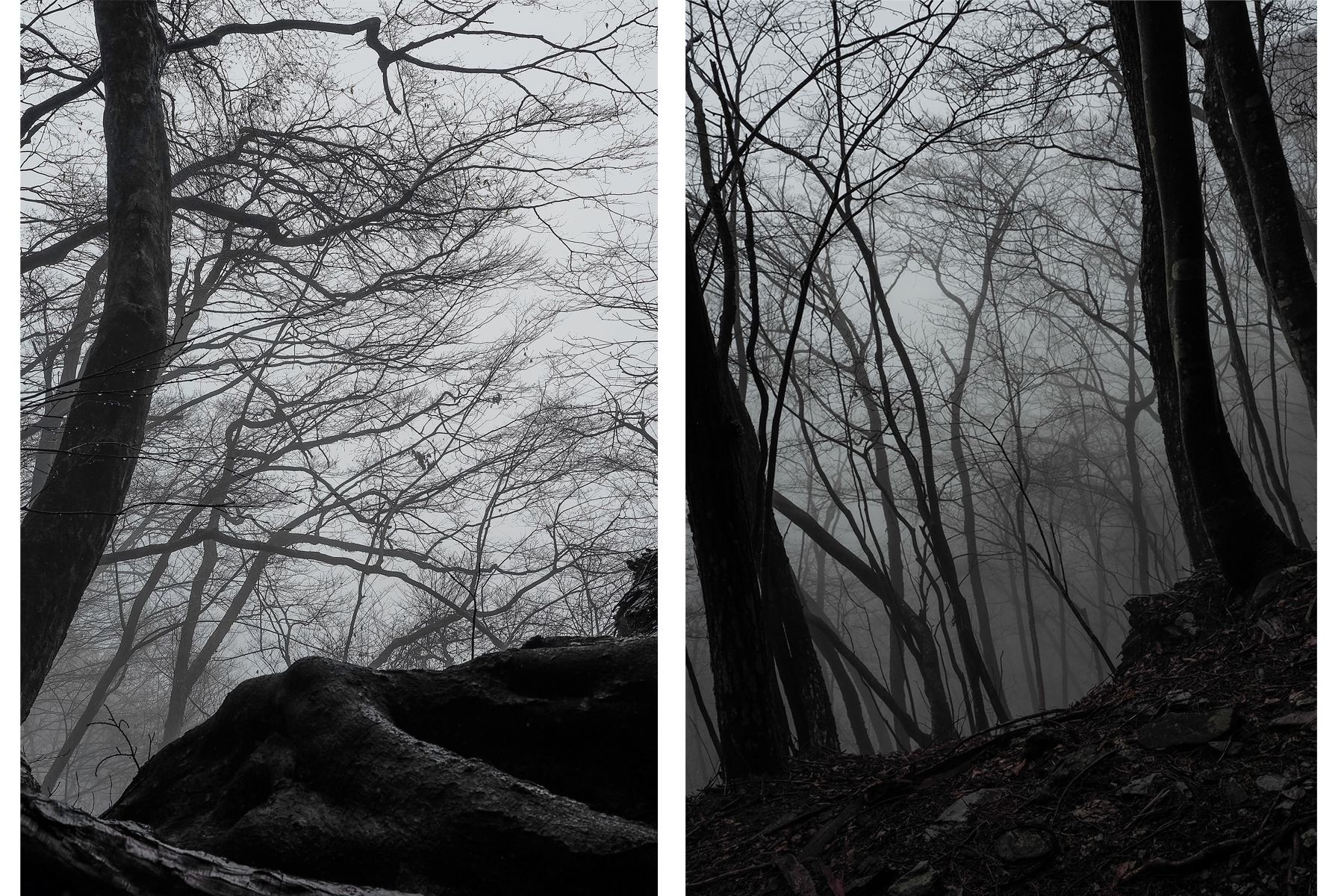

Photographer Michiko Hayashi had the opportunity to examine up close a similar relic owned by Chichibu resident Kanzo Tahira for her photobook “Hodophylax: The Guardian of the Path,” which won an award in 2018 at Kyotographie, an international photography festival held in Kyoto.

In 2009, Hayashi happened to visit Sapporo after learning that her mentor and acclaimed photographer Daido Moriyama’s works were being exhibited in Hokkaido’s prefectural capital. During her spare time she visited the Maruyama Zoo and saw a pair of Eurasian wolves frolicking in their quarters.

“I was blown away by their wild energy,” she says.

When northern Japan was devastated by the Great East Japan Earthquake, subsequent tsunami and the triple meltdowns at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant in 2011, Hayashi began contemplating how city-dwellers like herself were losing touch with nature. Pondering over the topic, she found herself stuck in an artistic slump. What revived her motivation was “Kenroki,” a 2012 documentary that public broadcaster NHK ran about wolf mythology and Hiroshi Yagi, a man who has been searching for the lost animal for, by now, half a century.

Hayashi began observing wolves at other zoos and visiting wolf-worshipping shrines in Chichibu and elsewhere. Then, in 2015, she learned that students at the Tokyo University of the Arts, her alma mater, were working on a project to reproduce 242 ceiling paintings of wolves at Yamatsumi Shrine in Fukushima Prefecture that had been destroyed by fire.

Situated in the village of Iitate inside the nuclear evacuation zone, the shrine was nevertheless open to the public following the 2011 disaster. However, it burned to the ground in April 2013, along with the century-old wolf paintings. The shrine was rebuilt in June 2015, and the plan was to repaint its ceilings with the images of the wolves based on digitally preserved archives of the original illustrations.

“I wanted to see the reproduction for myself, and volunteered to take photographs of the students at work,” Hayashi says.

Around halfway through the project, some of the paintings were exhibited at the Tokyo University of the Arts. Hayashi wrote about the event on her blog. Yagi noticed and reached out. The two became acquainted and over the next year traversed the mountains of Chichibu, visiting locations of wolf-sightings and ancient shrines featuring stone wolf statues, gathering material that was eventually compiled into her photobook.

“I find myself attracted to wolves, not just to the Japanese wolf but to all types of wolves,” Hayashi says. “It’s a feared predator on top of the food chain in many regions, but there’s something about the beast’s mystique that resonates deep within us.

“And in Japan, the wolf was both respected for protecting farmland from pests and feared for occasionally attacking humans. I think that duality reflects how our ancestors dealt with nature, a relationship that’s been lost to us, but to which I’m drawn.”

Contemporary depictions

One hundred and sixteen years after its supposed extinction, the Japanese wolf remains pervasive in art and literature, perhaps thanks in part to nostalgia for the premodern era when the beast roamed the lush mountains and forests of Japan.

In “Princess Mononoke,” Hayao Miyazaki’s 1997 animated film, a giant white wolf-goddess by the name of Moro is featured. Many have speculated that she was modeled after the white wolf that appeared in the misty mountains of Okuchichibu and guided legendary warrior Yamato Takeru to safety in a myth handed down at Mitsumine Shrine, a prominent wolf-worshipping shrine in Chichibu.

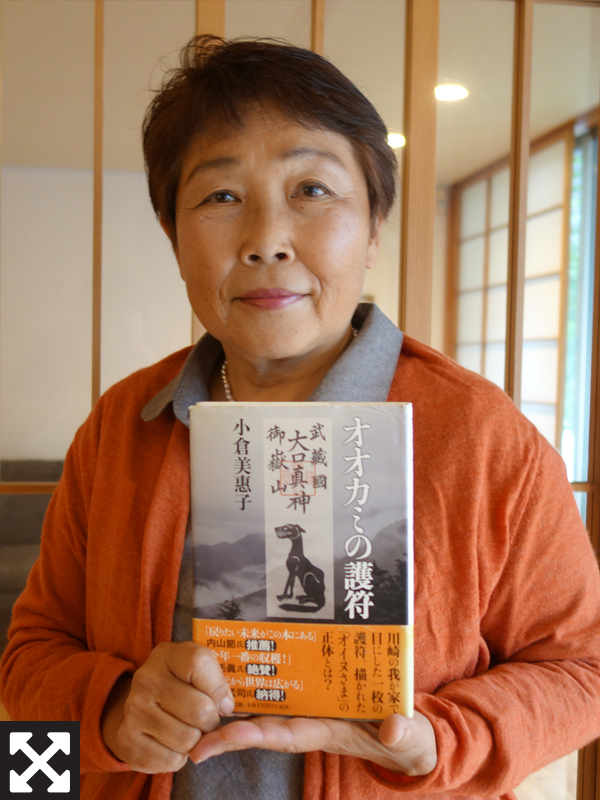

Writer and film producer Mieko Ogura produced a film and wrote a nonfiction book both titled “Okami no Gofu” (“The Wolf Talisman”) that explores the history and folklore behind the ofuda, or talismans, with wolf imprints, that are distributed by Musashi-Mitake Shrine in Tokyo’s western city of Ome and many other wolf-worshipping shrines in Chichibu. She is currently working to have the book translated into English.

As the talismans are believed to offer protection against fire, theft and other evils, there are still many households in the Kanto and Koshinetsu regions in central Honshu that place them by the entrances to their homes to ward off misfortune.

“In the increasingly secular society we live in, I feel there’s much to be learned from this centuries-old custom,” Ogura says. “The simple act of placing a talisman creates a space for worship, something that many households in Tokyo no longer have. I think it serves as a reminder of how prayer and respect toward things beyond human power was, and still is, an inherent part of our daily lives.”

Atsushi Miyamae, an architect I know who hails from the town of Ogano in Chichibu, for example, says his family still places wolf talismans collected from the local Ryuto Shrine by the entrance of their house.

“I grew up thinking this was a common practice,” he says.

Perhaps what continues to draw so many to the Japanese wolf is how such traditions have survived well into the 21st century despite the object of faith having disappeared from our sight over a century ago.

Uncertain future

On a crisp, sunny day in December 2019, the French photojournalist Delsol and I accompanied Yagi and members of his nonprofit for a hike up a mountain in Okuchichibu. We were going to observe their routine of retrieving data cards installed in trail cameras that Yagi has set up in an attempt to record images of the Japanese wolf.

The septuagenarian is known for having captured 19 photographs of a wolf-like animal dubbed the Chichibu yaken (Chichibu wild dog) in 1996. He has spent decades exploring the forests and mountains of the region in search of the beast, a saga I chronicled in the second installment of this series.

Climbing up steep, mostly untrodden paths, Yagi and his crew frequently checked the altitude and looked for colored tapes wrapped around tree trunks they had left to indicate where the camera traps were. We spotted occasional claw marks on bark suggesting the presence of moon bears — Japanese black bears, a subspecies of the Asian black bear.

“In the French Alps, we have many large valleys and pastures without trees that make it easier to observe wild animals with lenses or binoculars,” Delsol reflected after the trip. “That’s not the case here (in Japan’s mountainous terrain). That means it won’t be easy to prove that the Japanese wolf is still alive. But still, the dedication of people like Yagi is unbelievable, akin to a religious quest.”

After collecting data cards from five trail cameras, the party began its descent. Walking ahead of me with trekking poles in his hands, Yagi described how he was once charged by a moon bear and narrowly escaped by jumping out of its path at the last second — one of the many hairy episodes he has encountered in the wilderness over the years.

All too often we underestimate the risks involved in meddling with nature. Tales of wolf encounters from the Edo period (1603-1868) depict villagers terrified of being stalked by the predator, a deep-rooted fear that also led the animal to be venerated in certain parts of the country. But things have changed. The wild forests that the carnivores inhabited have been razed and replanted. The nation’s biodiversity has been permanently altered.

More than 90,000 animal species have been confirmed in Japan, of which 3,716 are endangered, according to the Environment Ministry’s “Red List 2020.” That’s up 40 from the previous year. The moon bear is no exception, likely to have already gone extinct in Kyushu and on the verge of disappearing in Shikoku. While they are still abundant in the main island of Honshu, in 100 years people may be describing the animal in the past tense, as we do with the Japanese wolf.

In 2019, a landmark U.N.-backed report by a panel called the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services said up to 1 million plant and animal species face extinction due to human activities.

“Ecosystems, species, wild populations, local varieties and breeds of domesticated plants and animals are shrinking, deteriorating or vanishing. The essential, interconnected web of life on Earth is getting smaller and increasingly frayed,” said Josef Settele, co-chair of the global assessment team. “This loss is a direct result of human activity and constitutes a direct threat to human well-being in all regions of the world.”

While reporting for this story, I’ve had the chance to talk to ecologists, folklorists, scientists, Shinto priests and amateur wolf enthusiasts, to name a few. They are each involved and invested in the Japanese wolf in their own capacities, but one thing seemed clear: For many, the animal represents both our follies as a species and the desire to reverse the damage humanity continues to inflict on the environment.

And that sense of irreversible loss and longing for a bygone era may be what has kept the animal alive in people’s faith and imagination, while driving those like Yagi to find the beast, however improbable such a prospect may sound.

Nestled among dense woodlands in the mountains of Nara Prefecture, a region steeped in ancient myths and legends, the sleepy village of Higashiyoshino is known for its famed Yoshino-brand cedar.

Beautifully weathered traditional Japanese-style homes lining its main street invite a visitor to hark back to the logging community’s olden days.

The alleys were empty and shops were closed during a weekend trip in January to the settlement of around 1,600 residents. Everything was quiet, save the gentle trickle of the Takami River and the occasional chirping of birds.

Close to the banks of the stream, along Route 16, a road that winds around the steep mountainside, stands a life-sized statue of a wolf. It was near here, at an inn in the district of Washikaguchi, that American zoologist Malcolm Playfair Anderson purchased the carcass of the last known Japanese wolf.

Its head tilted back and mouth open as if to emit a mournful cry, the bronze statue stands as testament to the cruel fate that the beast endured before its supposed extinction in 1905.

Piling on when a combination of canine rabies and distemper epidemics had diminished the packs, humans — who had for previous centuries worshipped the wolf as sacred — turned on the species and hunted down the survivors.

The nation’s wilderness lost its apex predator, leaving its ecological landscape permanently altered.

Hogetsuro, the inn Anderson stayed at, is gone. The mountains that once were home to a healthy population wolves no longer hear the primal howl that echoed across its hills and valleys.

Peering into the vast forests that still dominate the terrain, however, one can’t help but imagine the beast still prowling in its shadows, silently stalking its prey.

Near the statue is a time-worn stone monument that bears a simple haiku.

“The wolf has perished,” it reads. “Its spirit lives on.”