Chichibu, a mountain-ringed province on the northwestern edge of Saitama Prefecture, is known for its history of wolf worship. | OSCAR BOYD

In the first installment of a five-part series focusing on the search for the Japanese wolf, we explore the enigmatic fate of the mysterious beast and why, over a century after its supposed extinction, some believe it might still be roaming the forests and mountains of Japan.

ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Staff writer

There aren’t supposed to be any native wolves left in Japan.

Once roaming wild across the nation’s abundant forests and mountains, the Japanese wolf’s population was decimated by disease and humans hunting them down in the name of protecting livestock. By the early 20th century, the wolf was presumed extinct.

Yet to this day, the animal continues to transfix the minds of many. Worshipped in parts of the nation as a divine messenger and protector of farmland, it appears in numerous legends and folk tales handed down for centuries in rural communities.

It now lives only in our imagination.

Or so we thought.

In early 2019, I stumbled upon a peculiar tale — one that took me on an unexpected journey centered around the lost beast.

A resident of Chichibu, a mountain-ringed city some 70 kilometers northwest of Tokyo, claimed she saw a wolf. It was a cloudy winter afternoon, the middle-aged woman said, when a scrawny animal appeared by the rim of a small, empty pond in her yard. Their eyes met for a few seconds before the creature disappeared into a bamboo forest. “I’m confident it was a wolf,” she insisted.

The episode wouldn’t have been particularly noteworthy if it had taken place in, say, Canada or China, nations with sizable gray wolf populations. The Japanese wolf, however, officially became extinct in 1905. Surely the woman must have mistaken a feral dog or a fox for a wolf.

But what if she wasn't mistaken? What if an extinct apex predator still lives among us?

It soon became evident that this was much more than a quirky yarn about dubious wolf sightings.

It’s a story that brings to life a cast of colorful characters, weaving together a mix of ancient mythology and modern science against a backdrop of sweeping changes that befell this nation over the past several centuries.

Take the young American adventurer and the German physician, both of whom find themselves in Japan playing crucial roles in the animal’s zoological history.

Then there’s the aging mountaineer on a lifelong mission to find the missing creature, and the renegade academic on a relentless campaign to reintroduce wolves into the archipelago.

Meanwhile, DNA researchers from around the world are collecting rare genomic data to unravel the taxonomic puzzle surrounding the mysterious beast.

The Japanese wolf isn’t just another animal that vanished into the mist of extinction. Its tragic fate and the saga of those invested in understanding the enigmatic carnivore offer a unique window into this country.

Some see the wolf as a victim of Japan’s modernization, going so far as to say its disappearance represents the follies of the nation’s decision to open up to the West. Others see the creature’s death as symbolic of the environmental havoc wrought by industrialization and globalization. And for the few who believe in its survival, proving its existence could produce one of the greatest comeback stories of recent times.

So, is the Japanese wolf still alive, as the woman in Chichibu first informed me?

The search begins here.

The year of miracles

The year was 1905 and American explorer Malcolm Playfair Anderson was in Washikaguchi, a remote logging village in Nara Prefecture, south of Kyoto.

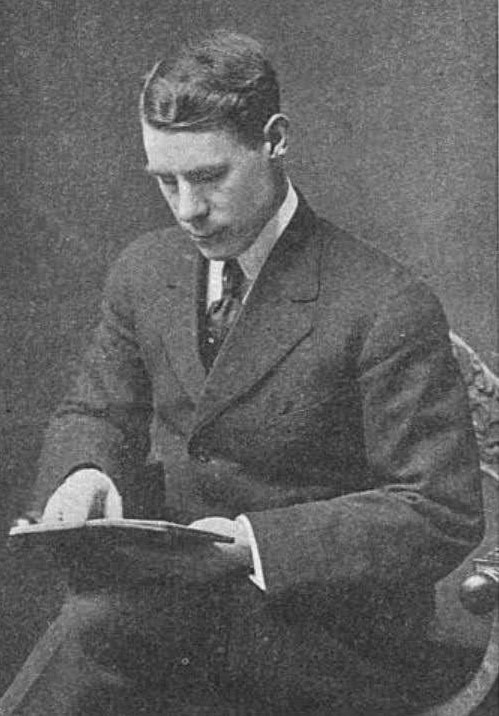

A 25-year-old Indianapolis native and Stanford graduate with a bachelor’s degree in zoology, Anderson had arrived at the port city of Yokohama in July the previous year to collect exotic animal specimens for the London Zoological Society under the patronage of the Duke of Bedford. He had spent the rest of that year traveling to central and northern Japan, including two trips to Hokkaido in September and November.

Upon returning to Tokyo at the end of 1904, he had run an advertisement in The Japan Times seeking an interpreter/assistant in preparation for an expedition to Aichi and Nara prefectures. The job eventually went to Kiyoshi Kanai, then a third-year student at the University of Tokyo. (Kanai would later serve as mayor of Suwa, Nagano Prefecture.)

Joined by Heijiro Ishiguro, an experienced hunter whom Anderson affectionately called “Black Stone” in reference to the Chinese characters used in his surname, the party acquired a hunting license from the Nara Prefectural Office and then, on Jan. 13, 1905, checked in at Hogetsuro, an inn at Washikaguchi, now part of the village of Higashiyoshino.

Scientists would call this time a year of miracles, when Albert Einstein wrote a series of papers that would transform how we view the universe, including his theory of special relativity and the famous equation E=mc². Imperial Japan was also in the midst of the Russo-Japanese War, which would eventually lead to Japanese control over Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula.

American zoologist Malcolm Playfair Anderson | WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Far from the winds of conflict that were gathering momentum in Asia and elsewhere, Anderson visited mountain hamlets and talked to hunters, accumulating and preserving specimens — racoons, weasels, wild boar and other creatures that didn’t have much value to locals.

The owner of Hogetsuro is said to have been perplexed and irritated by Anderson’s routine of skinning animals in his tatami-floored room, creating bloody messes that needed to be cleaned up.

It was here at the inn, however, that Anderson would obtain what will etch his name in history — the last known specimen of the Japanese wolf.

Much smaller than its counterparts in continental Eurasia and North America, the animal was venerated in certain parts of the archipelago as a divine messenger and guardian of the field, serving as a source of myths and folklore passed down for generations in rural communities.

By the time Anderson set foot in Washikaguchi, however, its population appeared to have been wiped out by a combination of rabies and distemper epidemics, with humans hunting them down in the name of protecting livestock. The wolf, after all, had not been inclined by nature to act as guardian of its fellow creatures.

On Jan. 23, three burly hunters visited Anderson at Hogetsuro, hauling in the carcass of a wolf. According to an article Kanai published in 1939 in the Manchurian Biological Society’s newsletter, the hunters were asking for more than ¥10 for the beast. Kanai tried to negotiate the price down by ¥4 or ¥5, but could not reach an agreement. The hunters left with their prize.

“Anderson’s disappointment was beyond words,” Kanai wrote. “Today, I can still vividly remember, 33 years later, the taciturn Anderson sitting on a Japanese-style balcony with one knee raised, muttering to himself that he should have bought it, that he might never be able to get his hands on it.”

However, Kanai suspected the hunters would return before the animal’s decomposition accelerated. They soon did, and Anderson purchased the wolf for ¥8 and 50 sen (the sen was worth one-hundredth of a yen at the time). The monthly starting salary of an elementary school teacher around then was approximately ¥8 or ¥9, making ¥1 roughly the equivalent of ¥20,000 by today’s standards.

“It was inconceivable at the time that this would be the last wolf collected in Japan,” Kanai wrote. “Smoking tobacco, the three hunters looked on while I skinned the animal with Anderson using a sharp knife. Judging from how its stomach had a bluish tinge and was starting to rot, it was likely captured (and killed) a few days before.”

The American left for the city of Nagoya three days later and would spend a total of two years and eight months in Japan, during which he traversed the islands of Hokkaido, Honshu, Kyushu and Shikoku, as well as to the Korean Peninsula and even the Philippines before returning to the United States in 1908.

He would head back to East Asia the following year, exploring China from its northern deserts to its western frontier of Tibet, and would visit South America on two collecting trips. He died during World War I on Feb. 21, 1919, when he fell from the scaffolding at a shipyard in Oakland, California, where he had volunteered to work after being unable to enlist in the army. He was 39.

The skull and pelt of the young male wolf that Anderson bought that day in Washikaguchi are stored at the Natural History Museum in London along with other specimens the zoologist shipped to the United Kingdom.

Perhaps Anderson’s observant eye had sensed the enigma that is the Japanese wolf. In the notes he left, he wrote: “The Wolf was purchased in the flesh, and I can learn but little about it. It is rare, some say almost extinct.”

The legendary creature’s story didn’t end there, however. Today, 116 years later, people are still following the traces of the elusive beast that once ruled the forests and mountains of Japan before disappearing in the waves of industrialization that swept across the nation in the early 20th century.

Modern genomics is unraveling the animal’s uncertain taxonomic status that some researchers say is the greatest mystery in Japan’s zoological history, while ecologists embrace the creature as a symbol of humanity’s destruction of biodiversity that has led to intensifying natural disasters and hotbeds for new viruses and diseases such as COVID-19.

Meanwhile, numerous accounts of sightings of wolf-like animals and reports of howls and discoveries of purported wolf scat, bones and fur have led some to believe that the Japanese wolf is still alive today.

Mysterious encounter

Fast-forward 115 years.

The creature appeared from the bushes as Michael Burke was driving home after a day spent hiking around Lake Usui, a man-made but nevertheless idyllic reservoir on the western edge of Gunma, a landlocked prefecture on the main island of Honshu.

Burke, a university English-language lecturer based in Tokyo, was crossing the border toward Karuizawa, an upscale highland resort in Nagano Prefecture where his family had temporarily relocated last year during the pandemic to avoid the bustle of city life. All his classes had gone online; his assignment was to work remotely until things settled down.

The car was cruising along the Usui Bypass, a narrow, 17.3-kilometer-long road winding through dense mountainous forests. It was around 4 p.m. on Saturday, May 30, and his two children were sleeping in the back seat, exhausted from the day’s activities.

“Suddenly, I saw what I thought was a fox emerge from the undergrowth,” Burke says. The animal looked mangy, he adds, noting that something about it seemed odd.

Burke slowed to a stop to get a better look at the thing, which had moved near the rear, right wheel of the vehicle. Upon closer inspection, he noticed it actually had a short and mostly yellowish coat with some darker faded-in patches. He opened the door and locked eyes with the beast, which stood still for 30 seconds or so — enough time for his wife, Emi, to lean over and also catch a glimpse.

Burke says the creature had a triangular head and greenish eyes, but it didn't look like a fox. Having grown up in the English countryside where foxes are plentiful, Burke is familiar with the creatures who are — unlike their Japanese cousins — quite brave. The canid also had a thin, black-tipped tail, he noticed, unlike the bushy tail of a fox. After a few moments, another car approached and Burke was forced to drive on.

“If I were to compare it to known dog breeds,” he says, “the closest description I could give would be a short-haired yellow Shiba with a wiry and mostly yellow coat. It was almost like that of a border terrier, though it was a bit more muscular than that. I think it stood a little taller than an average Shiba, but not much.

“Strange experience, anyway,” he adds. “I've never seen a dog like it. It looked a lot like the (taxidermied) specimens you can find pictures of online.”

He was referring of course to specimens of the Japanese wolf, an animal officially determined to have gone extinct in 1905.

Burke’s encounter is one of the most recent among hundreds of sightings reported over the past century of animals resembling Canis lupus hodophilax, the scientific name of the subspecies of gray wolf that was once endemic to Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu — and whose fate remains a mystery that captivates many to this day.

My own fascination with the animal derives from frequent visits to Chichibu, a mountainous city in Tokyo’s neighboring Saitama Prefecture where my Japanese mother built a weekend house nearly two decades ago. The region is a hiker's paradise, surrounded by peaks ranging from around 1,000 meters to 2,600 meters. It is also one of the centers of Japan’s wolf worship, home to nearly 20 shrines that deify the creature that once roamed the area's abundant hills and forests.

In 2019, I wrote a feature about the Japanese wolf for The Japan Times after talking to Rina Kambayashi, a Chichibu resident who claimed to have seen a wolf-like animal in her garden in December 2018. Sensing there was more to the story, I continued my research even after the piece was published, meeting Shinto priests, scientists, zoologists and others to learn about the animal and why, over a century after the last known wolf was killed, it still captures our imagination.

Rare sightings

Stories of wolves abound in Chichibu, shared by local elders such as Hisao Machida. The portly 85-year-old real estate agent holds forth in an office cluttered with dusty memorabilia near Seibu-Chichibu, a station around 80 minutes by express train from Ikebukuro, a major shopping and entertainment hub in Tokyo.

I was visiting him there one day when Machida passed along a tale he’d heard over 60 years before from two brothers who’d regularly gone hunting on 1,304-meter Mount Buko, which was, and still is, considered a sacred symbol of the region.

Machida says the older of the two was something of an eccentric who lived in a cave and frequently embarked on months-long expeditions to capture wild animals. His brother, on the other hand, was an expert trapper.

“The younger of the brothers told me there were wolves still inhabiting Mount Buko in 1935 or 1936, around the time I was born,” Machida says. That would be 30 years or so after the supposedly last known specimen of the Japanese wolf was purchased in Washikaguchi by Anderson.

The younger brother placed snares on the mountain to seize rabbits and deer, but would often find his prey being snatched by feral dogs.

“Angered, he assembled new traps to catch them, applying thick metal wires used in scaffolding. They worked just fine on dogs, but not when wolves were accidentally trapped,” Machida says. “The beasts would tear apart the devices and escape.”

One day, the brothers found a hapless wolf entangled and dead in a snare.

“The younger brother was petrified since we’d been taught that wolves are deities,” Machida says. “To hide any trace of the sacrilege, he told me he used a hammer to crush the beast’s bones into small fragments and buried them on Mount Buko. I asked for the location, but he never told us.”

There are plenty of similar reports of sightings and discoveries of the remains of wolf-like animals during the Showa Era (1926-89). In a period when Japan’s population and economy soared, the nation’s pristine natural forests were replaced by secondary and planted forests to procure lumber to feed housing demand.

Some cases made it into the papers — perhaps reflecting the public's nostalgia for a pre-industrial past.

In August 1973, the Yomiuri Shimbun ran a story about the discovery of a mysterious carcass in the Hatenashi mountains, a range covering Wakayama and Nara prefectures. Found buried in a landslide, the animal had thick fur and a large mouth, the newspaper said. It also had webbed feet, one of the traits possessed by wolves. Upon analysis, it was identified as a young raccoon dog.

In its Feb. 15, 1978, edition, the Asahi Shimbun printed a piece about a four-legged canid trapped in what is now the town of Taki in Mie Prefecture. While the animal died the same day it was caught, an academic quoted in the story said its physical characteristics showed a resemblance to the supposedly extinct wolf. It was eventually judged to be a fox.

While no such claimed sighting has been formally confirmed or officially endorsed to date, the accounts have led wolf enthusiasts to dedicate much time and energy to proving the existence of the animal. Contrary to the popular image of Japan being a high-tech wonderland home to glitzy cities, forests account for two-thirds of the nation’s total area. That abundance of nature has convinced some that the terrestrial carnivore may still be lurking somewhere in the mountains.

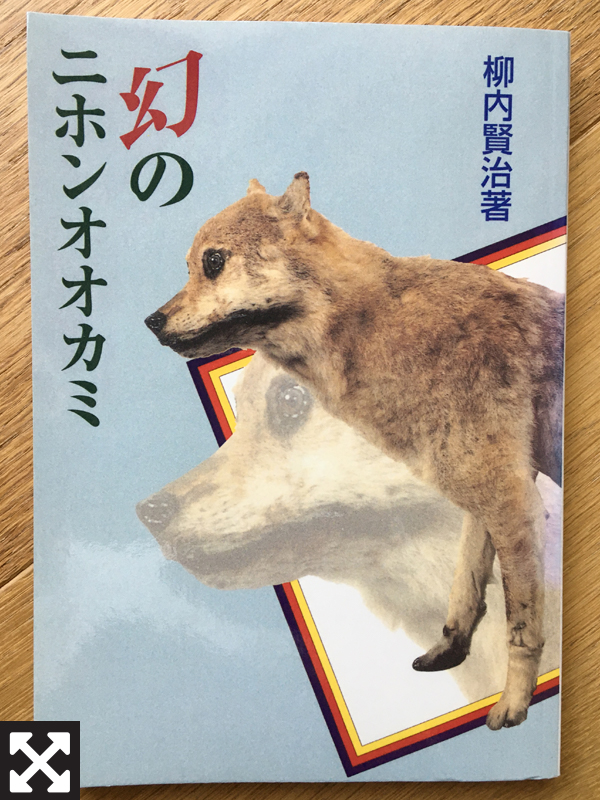

In his book of wolf-lore titled “Maboroshi no Nihon Okami” (“The Elusive Japanese Wolf”), the late journalist and forester Kenji Yanai details his own experience in 1964, the year Tokyo held the Olympic Games.

It was early morning on Sunday, June 7, when Yanai, his son and one of Yanai’s colleagues heard a deep howl reverberate through the valley near the base of Mount Ryokami, followed by another, shorter howl. The party was climbing the 1,723-meter peak at the northern end of the Okuchichibu mountains and was resting by a stream to catch some breakfast. Alarmed, they continued up the path nonetheless, but soon saw what appeared to be a domestic dog fleeing from an indistinguishable predator toward a nearby hamlet.

The strange animal appeared some time later after the trio stepped into a clearing. The path they were taking detoured around a natural depression, and they saw the creature standing on the other side of the dip. Yanai, then 48 years old, wrote that he first thought it was a German shepherd, but noticed it bore an air of untamed roughness. It had muscular legs, rather small, pointed ears, a straight tail and grayish-brown fur.

The trio froze, sensing danger, as the beast glared at them before walking away.

Yanai and his party continued trekking, but soon found the carcass of a rabbit — a lump of bloody intestines and bone fragments that indicated a recent kill. Noticing how the dead animal’s fur wasn’t scattered about, Yanai’s son said he had read somewhere that the Japanese wolf devoured the coat of rabbits along with the meat.

The party was terrified, Yanai recalls, and made ad hoc spears out of branches for protection. Yanai was so scared, he writes, that he didn’t remember much of what happened during the rest of the journey. The experience prompted him to climb more than 500 mountains across Japan in the years that followed in search of traces of the animal.

Divine intervention

Mount Ryokami, where the sighting took place, is home to Ryokami Shrine, also known as Ryuto Shrine. Founded in 1223 in Ogano, a scenic town on a plateau in the Chichibu region, the weathered shrine has a long history of wolf worship. Stone wolf statues greet parishioners who visit to purchase ofuda (protective paper talismans). These feature illustrations of a wolf along with the inscription “Okuchi no Magami” (“Large-Mouthed Pure God”).

Yoshiomi Takano, the 21st-generation head priest of the shrine, says the sanctuary is dedicated to Japan’s founding gods Izanagi and Izanami.

“It’s unclear when exactly the institution began venerating wolves,” Takano says, but, according to legend, it involves the founder — a priest named Makabe Gondayu.

During a major conflict known as the Zenkunen War (1051-63), Gondayu embarked on a journey to pray for the victory of his master, the warrior Minamoto no Yoriyoshi who was waging battle against the Abe clan.

Upon arriving at the foot of Mount Ryokami, he was overwhelmed by the mystical ambience emanating from the mountain and set up camp. One night, he received a divine message instructing him to subdue a mischievous dragon living in a pond to the south of the mountain. In exchange, his lord would be victorious in battle.

Gondayu followed the rather complicated set of orders and enshrined the dragon’s angry spirit in Mount Ryokami. He then transferred a divided tutelary deity from the Suwa Shrine, one of the oldest and largest networks of shrines in Japan, to the base of the mountain. Finally, he established a branch of a Hachiman Shrine next to the Suwa Shrine and, lo and behold, the dragon ceased to trouble the villagers and Yoriyoshi was able to defeat his enemy.

With his work done, the priest returned to his home on Mount Tsukuba and left the management of the shrines to Takano’s ancestor, Kichiji. And here’s the twist: One night, a revelation in a dream told Kichiji to transfer the shrine of the dragon to an untrodden mountaintop, and said that a yamainu — literally “mountain dog,” synonymous with wolf in this part of the country — would guide him to the spot.

“I’ve never in my lifetime met anyone who has seen wolves, although I’ve heard of folks who have sensed their presence,” says Takano, who is now in his early 60s. “Some say if you don’t take proper care of the talismans, wolves will come after you.”

Takano was once gifted 5 kilograms of rice by a resident of Saku, a city in neighboring Nagano Prefecture that has been sending pilgrims over mountains to collect Ryokami Shrine’s wolf talismans. The rectangular sheets are then pasted on the entrances of homes to protect inhabitants from fire, burglary and other misfortunes.

The man told Takano the talisman saved his life when he accidentally set his foot alight with a candle after a funeral.

“He said he would have been burned alive were it not for the special powers of the wolf,” Takano recalls.

To this day, the shrine observes various rituals dedicated to the wolf god. Priests and their families are prohibited from eating four-legged animals and ceremonial rice is offered to the beasts during the New Year’s holiday.

Takano says he’d occasionally receive travelers like myself curious about the region’s history and wolf worship. He particularly remembers one man who came to visit his father in the late 1960s, asking for information about wolf sightings. It may have been the aforementioned Yanai himself.

Missing pieces of the puzzle

The Chichibu region’s rich wolf mythology and the traditions practiced by Ryokami Shrine and other wolf shrines continue to intrigue many amateur naturalists.

Kikuo Yamashita, a manager at Tokyo’s Arakawa Natural Park who counts beekeeping and fishing among his hobbies, has been visiting the region for two decades. He and his wife finally decided to purchase a vacation house on the outskirts of Chichibu in 2018.

Several years ago, Yamashita went to check on a beehive he had set up near Hananoya, a rural ryokan (Japanese-style inn) near Bushu Hino Station on the Chichibu Railway. Walking down a narrow gravel path adjacent to a small graveyard, he came upon the carcass of a dog-like animal. The whole skeleton was still there, he recalls, with some bits of fur left.

“It didn’t seem like a dog, though. Maybe because it had rather large teeth. I instinctively thought that it could be a wolf,” Yamashita says. “If a dog had an owner, it wouldn’t be left to perish in the middle of that path.”

The remains of the animal gradually disappeared as the weeks went by, and eventually they were all gone.

“Something wasn’t right,” he says, somewhat regretfully. “I should have picked up some of its bones.”

The notion that a species long deemed extinct may still be among us is intoxicating. Proving the Japanese wolf’s continued existence, though, is a quixotic goal. Most academics deny the possibility, citing the lack of hard evidence along with the dramatic changes that befell the nation’s ecological landscape in the 20th century.

Still, once in a blue moon, discoveries are made that challenge that verdict and raise new questions about the taxonomic status of the animal that was once Japan’s apex predator. That, as we shall see in the next installment of this story, was the case with a series of photographs taken in 1996 by Hiroshi Yagi, a man who has been pursuing the elusive beast for the past half century.

In October that year, Yagi saw through his car’s front window a sinewy canine with pointed ears and a black-tipped tail standing at the edge of a lonely forest road. The encounter was the fruit of his decades-long efforts to track down the creature, and would provide one of the most convincing accounts to date that the Japanese wolf, an animal now part of the Environment Ministry’s extinct species list, may still be prowling in the nation’s wilderness.