LONGFORM

In search of

Japan’s lost wolves

Territorial threat

Japanese cedar and cypress forests in the Okuchichibu mountains | THOMAS DELSOL / HANS LUCAS

Industrialization and deforestation played a part in the Japanese wolf’s supposed demise at the turn of the 20th century. More than 100 years later, the ecological crisis is still with us.

ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Staff writer

Glaring ominously over rice paddies, chestnut fields and apple orchards dotting Japan’s rural landscape, shaggy mechanical beasts with flashing red eyes and bared fangs are doing what the creature they’re modeled after can no longer be counted on — protecting farmland from a booming population of wildlife pests such as deer, wild boar and bears.

Called “Monster Wolf,” these robotic canines are the brainchild of Ohta Seiki Co. and were created in response to the growing menace of crop raiders that inflict billions of yen in damages annually. The solar battery-powered wolf can turn its head from side to side and make dozens of varieties of howling, barking and gunshot sounds when the motion detectors are activated.

“Some think this is just a gimmick, but the results so far prove it’s working,” says Shushi Sasaki, director of Wolf Kamuy, the company in charge of Monster Wolf’s sales and maintenance. Indeed, sightings of wild bears rummaging for food in Takikawa, a city in Hokkaido, have dropped drastically since they were introduced last year. Similar success stories are reported in dozens of locations across the nation where the metallic wolves have been deployed.

Ohta Seiki Co.’s Monster Wolf was invented to scare away crop raiders.| COURTESY OF WOLF KAMUY

But why does the machine take the form of a wolf, an animal believed to have disappeared from Japan over a century ago?

“Ohta Seiki initially sold a pest repellent combining flashing LED lights with blazing sounds, but realized the product could be more effective with a threatening outward appearance,” Sasaki says. “Zoologists advised that the wolf was the natural predator of wild bears and other animals, so we proceeded to experiment with the Yezo deer kept by the Tokyo University of Agriculture’s Okhotsk campus in Hokkaido.”

Perhaps it's embedded in their DNA. The deer were petrified by the robot’s frightening looks, Sasaki says, and the machinery company found itself a hit product.

Before its supposed extinction in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, the wolf presided over the archipelago as an apex predator, worshipped by farmers as guardian of the field for preying on deer, wild boar and many other animals.

In its absence, however, and with climate change, a decrease in the numbers of hunters and a government-led program that replaced massive swaths of native forests with secondary forests, Japan has seen a rapid proliferation of voracious herbivores and omnivores such as deer and wild boar that ravage scenic woodlands. The extensive damage to agriculture and the environment has led not only to the invention of the Monster Wolf, but also to calls for reintroducing real wolves into Japan to restore the country’s ecosystem.

License to kill

Sitting in a cedar forest behind my family’s weekend retreat are a couple of trail cameras I installed on tree trunks — tiny windows into the ecological landscape of the world’s third largest economy.

The two-story house sits on the outskirts of Chichibu, a mountain-ringed province on the northwestern edge of Saitama Prefecture. Home to impressive peaks and ancient villages with numerous trails leading up into the highlands, the region — known for its history of wolf worship — teems with wildlife, attracting fans of hiking, fishing, rafting and, during the annual hunting season that kicks off on Nov. 15, those with gun and trap licenses looking for game.

And there are plenty — perhaps too many when it comes to certain crop raiders such as deer and wild boar.

Lacking both financial and human resources to kill those pests, aging and shrinking municipalities are struggling to deal with the animals’ expanding population and the damage they inflict. Nationally, that figure was ¥15.8 billion in 2019, with deer, wild boar and monkeys accounting for ¥5.3 billion, ¥4.6 billion and ¥900 million, respectively.

Hunters work to cull the herds, of course. However, after hitting a high of 518,000 in 1975, the total number of licensed hunters plunged — finally leveling off around the 200,000 mark in recent years, according to the Environment Ministry.

In 2016, for example, the ministry counted 199,700 registered hunters. However, around 60% of those were over 60 years old, raising concerns that many elderly hunters will be retiring their guns in the coming years.

“Most hunters here are in their 70s,” says Takeo Koike, head of the Arakawa branch of the 29-member Okuchichibu Ryoyukai hunting association. “I know a man who is 90 years old who still goes out with his shotgun. It’s getting difficult to recruit the younger generation.”

Koike’s family has lived for centuries on a plot of land about a kilometer from our house. The area was called Arakawa Village before being merged into the city of Chichibu in 2005. Its old name was a nod to how the community is nestled near a steep valley leading down to the Arakawa, a 173-kilometer river that originates on Mount Kobushi in Chichibu and empties into Tokyo Bay.

Wearing a bright orange vest, Koike, who is almost 70, tells me at my Chichibu residence that he acquired a hunting license when he was 50 after wild boar trampled and destroyed a path leading up to his family’s gravesite. “It prevented us from paying respect to our ancestors, so I decided to take matters into my own hands.”

After passing an exam that involved both written and practical assessments, Koike received permits to trap and possess sporting guns and purchased his gear at a local gun shop. He uses a shotgun with nine-pellet shells, an airgun and wire traps that sell for around ¥5,000 to ¥8,000 a set.

Outside of the official hunting season that ends on March 15, Koike’s team and other hunting clubs are allowed to cull so-called nuisance animals. During the period lasting from Aug. 1 to Nov. 14 last year, for example, the Arakawa branch could kill a maximum of 15 monkeys, 60 deer, 20 boar, 15 masked palm civets, 15 racoons and 15 tanuki (racoon dogs indigenous to East Asia).

Kills bring monetary prizes: Depending on the municipality, anywhere from ¥5,000 to ¥30,000 is paid for each deer. Applicants for the subsidy are typically asked to present photographs and body parts (tail, ears, etc.) of the same animal as proof.

“Monkeys are a real problem now, hanging out near homes and ruining vegetables such as pumpkins, corn, tomatoes and eggplants,” Koike says. There are three troops active in the Arakawa area, he explains, each comprising around 20 primates. In Japan, monkeys typically refer to the Japanese macaque, or snow monkeys native to the country.

I’ve captured one of the troops on my trail camera — a group of over a dozen macaques, including infants, hopping across a forest opening. The camera traps are motion-sensitive with infrared night vision and activate whenever anything moves in their fields of view. My traps are set to record video for 20 seconds before going back to sleep, and that was enough to get a good look at the feisty animals.

Raccoons, wild boar and, occasionally, moon bears appear, but by far the most abundant are Japanese deer. There are so many of them that around 80% of animals recorded on my data cards are deer. You can hear their shrieks almost every night as families scavenge the fields for food.

A herd of deer recorded on a trail camera in Chichibu, Saitama Prefecture | ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Deer invasion

In many regions of Japan, including Chichibu, the deers’ grazing is impacting plant growth and diversity. The large herbivores strip bark off the trees and devour shrubbery and fallen leaves, making the ground bare and prone to landslides and leaving less food for other species.

Deer also feast on crops and damage farmlands, and are even leading to a rise in traffic accidents. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries reported that in the fiscal year that ended March 31, 2017, approximately 7,000 hectares of forests were damaged by wild animals. Of that damage, 78% was caused by deer.

The explosion of deer population in recent years has been attributed to conservation efforts, warming winters, the aging and decreasing numbers of hunters and the supposed extinction of its main predator, the Japanese wolf, over a century ago.

Until the late 19th century, deer had been widely distributed across lowlands in Japan, but overexploitation and habitat loss caused by human activity diminished their numbers. Legal protection acts were established in the 1970s, thereafter the numbers saw a recovery and the creature’s geographic range expanded.

In fact, their proliferation was so fast that the government decided in 2013 on a national goal to halve the numbers of deer and wild boar by 2023. That was followed by a revision to a law on wildlife protection and hunting management the following year to provide financial support to local governments.

Efforts to curb the deer and wild boar populations, including the use of electric fences and wildlife monitoring systems, and the culinary promotion of game meat, seem to be yielding some results.

The Environment Ministry estimates there were 2.44 million deer and 880,000 wild boar in Japan in 2017, down from 2.72 million and 890,000 the previous year. Meanwhile, 602,900 deer and 640,100 wild boar were captured in 2019, up from 572,300 and 604,800 the previous year.

Still, with two years to go, that’s far from the goal of halving the deer population to a little over 1.2 million.

Radical ecological solution

With human predators unprepared to fully meet the challenge, some are calling for a simple, albeit controversial, solution: reintroduce wolves to Japan in order to protect farmland and restore the ecological balance of affected areas.

Japan was once home to two types of wolves: the Hokkaido or Ezo wolf (Canis lupus hattai) native to the northern island of Hokkaido, and the Japanese or Honshu wolf (Canis lupus hodophilax) endemic to the islands of Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu.

Deified by Hokkaido’s indigenous Ainu people as Horkew Kamuy (Howling God), the Ezo wolf hunted the Yezo deer, among other animals. But the carnivore’s main prey became scarce during the Meiji Era (1868-1912) when settlers from Honshu chased deer for meat and leather. Instead, it began targeting horses — much to the dismay of ranchers.

In response, a bounty system was introduced and American rancher Edwin Dun launched a campaign to exterminate wolves using strychnine-laced baits. Meanwhile, record-breaking snowfalls in 1879 pushed deer to near-extinction, further diminishing the wolf population. This subspecies of the gray wolf is thought to have gone extinct in 1896.

The last known specimen of the Japanese wolf, on the other hand, was purchased by American explorer Malcolm Playfair Anderson in 1905. Smaller than the Ezo wolf, it was nevertheless worshipped by farmers as protector of the field during the Edo Period (1603-1868).

The wolf’s revered status gradually eroded after it began preying on horses in the 17th century. According to records, some of the earliest wolf bounties were offered by the Morioka domain in the northern Tohoku region. Studies indicate that, at one point, 35% of Morioka’s horses were killed by wolves, extending the notion that the beast was an enemy of humans.

Meanwhile, rabies appeared among dogs in the mid 1730s and rapidly spread across Japan. The disease eventually reached wolves and turned some into crazed man-killers, triggering large-scale wolf hunts. Deforestation, coupled with a decline of the deer population due to overhunting and the evolution of firearms, also led to the steady depletion of the wolf population.

And during the Meiji Restoration, killing wolves became national policy, while deadly canine distemper epidemics transmitted from Western dogs infected wolves. All these factors are said to have played a part in the animal’s disappearance from the archipelago.

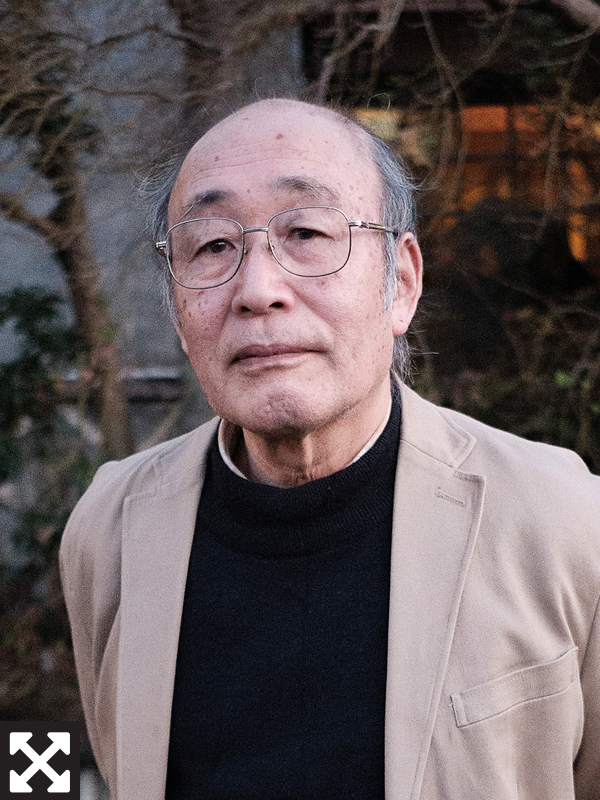

“According to my estimate, there were probably around 5,000 to 10,000 Japanese wolves and 2,000 to 3,000 Hokkaido wolves in Japan,” says Naoki Maruyama, who heads the Japan Wolf Association, a group that has been lobbying for the reintroduction of wolves.

“Ideally, I’d like to see around 40 to 50 wolves imported to each of Japan’s main islands, especially in rural mountainous areas with high deer populations wolves can prey on,” he says.

Maruyama, an honorary professor at the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, tells me that the idea first dawned on him in 1988 when he happened to see a pair of wolves in Poland’s Bieszczady National Park while visiting for an academic conference. While he had been researching the conservation management of deer and wild boar, this encounter provided the missing piece he’d been looking for.

Starting that fall, he began presenting his idea to reintroduce wolves to academic circles.

“But the more I made my case, the more people thought I was crazy,” he says. “There’s a deep-rooted fear of the animal in contemporary Japan. It’s seen as a man-eating beast, like how it’s depicted in ‘Little Red Riding Hood.’”

Frustrated, he decided to launch his own organization in 1993 to appeal directly to the public.

Maruyama points to the well-documented ecological benefits of the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the United States, and says similar restoration of biodiversity is possible by unleashing gray wolves imported from Russia, China or North America to the Japanese countryside in enough numbers to prevent inbreeding.

While the Japanese wolf was considerably smaller than the wolves Maruyama wants to import, he says the animal’s diet and size will adapt to the landscape and available prey. But he admits that convincing the public of the merits of such a project has been challenging.

“Part of this problem is the strong resentment toward alien species and the dangers they may pose,” he says, recalling a lecture he gave around two decades ago in Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture.

“On the morning of the event, I received a call at my home while I was getting ready to leave,” he says. It was from an angry mother in Tochigi who had read a newspaper article about the gathering.

“What if my child is attacked by wolves while commuting to school!” the woman yelled. “When I arrived, there were sound trucks parked outside the venue with rightwing nationalists condemning the idea of introducing foreign wolves to a nation that was home to the Japanese wolf.”

While surveys conducted by Japan Wolf Association show opposition to the plan decreasing over the years, major inroads are yet to be made. Ecology and animal welfare groups point out that Japan has undergone significant industrialization since the Japanese wolf was last seen. Trees have been replanted, rivers dammed. Cities are leaving an ever-growing urban footprint.

How will we know if wolves will be able to survive without causing us harm? Maruyama says answers to all these questions are detailed in his books and on his organization’s website. But his main concern now, he says, is that he is running out of time.

“I’m 78 years old,” he says, “and have been contemplating how many more years I have to be actively engaged in this mission.”

Changing face of forests

The primeval howls of wolves went silent over a century ago in Japan’s forests, vast portions of which were then cut down during World War II to support the nation’s military. Following the war, a spike in demand for timber to feed reconstruction needs saw even more forests disappear, prompting the government to launch a nationwide reforestation campaign. Millions of hectares of beech trees were wiped out and replanted with fast-growing conifers such as cypress and cedar.

With Japan’s trade liberalization of forest products in 1964, however, cheap foreign imports began entering the market and the evergreens were gradually left unattended, releasing massive amounts of pollen in the atmosphere and triggering hay fever affecting a significant portion of the population to this day.

“These unharvested forests are also impacting biodiversity,” says Yumiko Tsuruda, executive director of The Nature Conservation Society of Japan.

“Japan’s forests account for two-thirds of the nation’s total area. But 40% are artificially planted forests of mostly cedar and cypress trees,” she says. “Cheap foreign imports mean there is no longer an incentive to invest the time and effort to conduct proper pruning and thinning to care for them. And akin to the situation with hunters, the forestry workforce is dwindling. The result is dark, dense, unhealthy forests.”

Tsuruda says Japan’s woodlands had been home to a diverse range of deciduous and broadleaf trees providing the necessary ecosystem to support a wide variety of species, including wolves.

“But the degradation of the artificial monoculture forests we see occupying our countryside now has led to a loss of the multifaceted functions of forests,” she says.

Overcrowded evergreen forests limit undergrowth, causing surface soil erosion while cutting availability of minerals and vitamins for insects. Meanwhile, nitrogen is flowing from the older commercial plantations into nearby streams and other water sources during rainfall and snowmelt, causing algae blooms.

“These untended forests are increasingly triggering flooding and landslides,” Tsuruda says.

This is something I can see for myself actually. The forests surrounding my family’s Chichibu cottage are mostly cedar. The gravel road running by the house leading up to the woodlands occasionally gets swept by mudslides during typhoon season and sudden downpours — natural disasters that seem to be occurring with alarming frequency.

Decades of misguided forestry policy are not only impacting insects and water quality. Chopping down beech forests has cost local bears their habitat. The moon bear, known for its distinct white V-shaped patch on its chest, is considered extinct in Kyushu and only a dozen or so specimens are believed to survive in Shikoku.

Efforts are underway to return these forests to a more natural state. Take Akaya Forest, a state-owned 10,000-hectare plot of woodland in the mountains of Gunma Prefecture that the Nature Conservation Society of Japan manages with Forestry Agency staff and local citizens.

Under the project, the area is being replanted and restored back into more diverse, mixed forests and meadows that can harbor animals like the golden eagle. The nearly extinct raptor has suffered from a lack of prey, such as hare, in the almost bare understory of timber plantations.

And as with other forests, Akaya is also home to a significant deer population. Tsuruda says the organization has introduced a unique method to curb the numbers.

“The idea is to control and maintain the number of deer before they grow out of hand,” she says.

Mineral licks — deposits of salt and other minerals where animals can go to lick essential nutrients — are strategically placed and monitored in areas with high concentrations of deer to systematically attract the herbivores to kill them.

Such endeavors, however, still remain rare, and Japan’s abandoned plantations and booming deer population continue to hurt the ecosystem.

“When wolves roamed our nation’s wilderness, the forests were brimming with life. A diverse array of trees, plants, birds and other animals each played its part in maintaining nature’s balance, allowing wolves to prosper for generations,” Tsuruda says. “But I’m afraid we’ve lost that potential. We need to figure out how to rejuvenate our forests to levels worthy of the Japanese wolf.”

Call of the wild

Sitting atop a steep stone staircase overlooking the old village of Arakawa in Chichibu is Wakamiko Shrine. As with other wolf-worshipping shrines that occupy the province, statues of wolves guard the torii gate at the entrance of the institution, founded 1,300 years ago during the Nara Period (710-794).

Tadao Kasahara, who has been head priest there for more than three decades, doesn’t know exactly when the shrine began venerating wolves. It appears the four-legged deities were “borrowed” from Ryomen Shrine, a wolf shrine resting deep in the mountains of Chichibu’s Otaki district, during the early Meiji Era.

In mountainous Chichibu, arable land is scant and the poor soil holds little water. Only a few crops are suited for the terrain and climate, Kasahara says, speculating that farmers prayed to wolves to protect what little resources they had from being ravaged by other wild animals.

“Chichibu’s dry land isn’t fit for growing rice, so villagers of Arakawa resorted to planting buckwheat used to make soba noodles and mulberry, whose leaves are food for silkworms that supported the region’s sericulture,” he says. “I believe they prayed to wolves to protect their crops and to help them secure enough food on their tables to get by during difficult times.”

It has been 116 years since the Japanese wolf is said to have vanished from the nation’s forests. Still, there have been persistent reports of claimed sightings of wolves in different parts of the country. Kasahara recalls a tale he used to hear from a good friend who would have been around 90 if he were still alive.

“He used to boast about hearing a wolf howl in the mountains of Mitsumine,” Kasahara says, referring to the peaks that are home to Mitsumine Shrine, a mecca for the region’s wolf worship.

“But that must have been around 50 years ago,” he says. “Today I can only hear monkeys calling each other.”

In an article titled “On the Extinction of the Japanese Wolf,” researcher John Knight says the “Honshu wolf — whether extinct or not — continues to symbolize something much larger than itself, something about modern Japan as a whole.”

“The question of the existence or extinction of the wolf seems to be bound with that of the scale of change that has occurred in the mountains,” Knight writes. “It is as though the issue of the wolf’s existence is animated by a local nostalgia for the yama (mountains) of the past.”

That idea of the wolf as the embodiment of nature and the drastic environmental changes that befell Japan over the past century has drawn numerous artists, writers, photographers and others to the beast. And the rich trove of folklore and legends passed down in Chichibu and other rural, mountainous communities offer a window into the creature’s ecological and cultural significance and why it continues to inspire so many.

“The wolf is a symbol both of the wild yama and of its control,” Knight writes. “Perhaps that is why a formally nonexistent animal continues to preoccupy upland dwellers. If the wolf is extinct, it is not obsolete.”