Hiroshi Yagi's trail cameras are equipped with passive infrared motion detectors, which react and record whenever an animal enters the field of view. | OSCAR BOYD

Hiroshi Yagi has devoted most of his life trying to prove the existence of the Japanese wolf, a saga that began with a series of piercing howls he heard more than half a century ago.

ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Staff writer

A light drizzle enveloped Hiroshi Yagi’s Toyota van as it hummed along a forest road near Lake Naguri in Saitama Prefecture. It was around 4 p.m. on Oct. 14, 1996, and Yagi was on his way back from scouting locations at which to set up equipment that could broadcast recorded wolf howls in the mountains to prompt real howls in response.

He approached a particularly narrow stretch sandwiched between a steep cliff to the right and a valley leading down to a stream to the left. Yagi slowed the vehicle to a crawl, hoping he wouldn’t be trapped by an oncoming car. The one-year safety check on his automobile had expired and he couldn’t risk being caught speeding or having an accident.

As the path widened again, he noticed a four-legged animal making its way up from the creek.

“It looked familiar, but I couldn’t immediately place it. The creature walked across the road in front of me,” recalls Yagi, who at that time was 46. “Then it dawned on me that this could be it — I could have found what I’d spent decades searching for.”

Yagi stared at the beast for around a minute, etching its physical characteristics into his mind. Giddy with excitement, he reached for his mobile phone and called Yuriko Inoue, a dog and wolf researcher whom he considers his mentor. After a second attempt failed, Yagi realized that his phone had no reception in the mountains.

“For a moment,” he says, “I considered stepping on the gas and running it over,” an act that would have given him a specimen that could be scientifically analyzed. “But then I thought of my dog, who had passed away in my arms just a few days earlier. I couldn’t stomach the idea of killing an innocent animal that looked so young.”

After parking his car, he carefully opened the door and tiptoed toward the trunk, where he had stowed his Minolta 707 camera. The animal stood still as Yagi started fidgeting with the device’s settings.

Finally, “I looked up when I was ready, and it was gone,” he says.

Disappointed, but elated with the surprise encounter, he decided to move his vehicle when a car approached from behind. The driver informed him that he had seen the canine some distance back on the same road.

Not knowing which direction his quarry had taken, Yagi struggled to make a U-turn on the narrow road. He drove back up for around 10 to 15 minutes but couldn’t find any trace of the animal. He gave up, made another U-turn and when he drove back down he saw it walking ahead of him, along the right side of the road. Entranced, Yagi grabbed his camera and fired away, successfully capturing the creature in 19 photographs that confound taxonomists to this day.

Satisfied with the shots and seeing that it wasn’t about to flee, Yagi stepped out onto the asphalt. He stood about a meter away from the animal, which looked hungry. Yagi pulled out a senbei rice cracker and offered it.

“But it just gave me a troubled look and didn’t take it,” he says.

Then it trotted into the bushes and disappeared. All this happened in a matter of 30 minutes or so.

“It was as if I were in a dream,” Yagi says.

The images stirred up a media frenzy after Yagi went public with them the following year, with newspapers, magazines and television shows featuring the photographs and debating the possibility that the Japanese wolf, an animal thought to have gone extinct in 1905, might still be alive.

Many pundits brushed away the idea, suggesting that the creature was probably just a domesticated dog turned wild. For Yagi, however, it was proof that his pursuit that had begun with a series of haunting howls he heard one night 27 years before was bearing fruit.

Hunting for evidence

Animal enthusiasts have long been searching for traces of the Japanese wolf in the mountains and forests of the archipelago, collecting anecdotal reports from those who claim to have encountered the mythical creature in an effort to prove that it is still among us.

While there haven’t been any conclusive discoveries supporting the theory to date, advances in scientific technologies mean researchers are now capable of using MRI scans and DNA samples to determine whether the sightings are of wolves rather than feral dogs.

Yagi has been at the forefront of the quest to find the necessary evidence to bring the animal back from extinction and, by doing so, restoring its status as Japan’s revered apex predator. While inspiring fear, the beast was also venerated in certain parts of Japan as a messenger of the gods and protector of farmers from wildlife crop raiders.

That journey has been arduous and challenging. The lack of any official funding means people have had to rely on their own resources to support the search. Ad hoc traps, trail cameras and old-fashioned legwork are among the primary means employed by those invested in finding the elusive canine.

I met Yagi for the first time in April 2019 while reporting on a sighting of an unidentified wolf-like animal in Chichibu, a mountain-ringed city of 63,000 people roughly 70 kilometers from Tokyo. I wasn’t sure what I was getting myself into, but found the notion of a creature supposedly extinct for 100 years resurfacing in the 21st century refreshing. I searched online for similar sightings, and found Yagi’s blog, where he meticulously records his own research on the phenomenon and the numerous reports of possible wolf sightings, droppings and howls sent to him from across the nation.

We agreed to meet. He picked me up at Seibu-Chichibu Station in his minivan adorned with a rear window sticker of a canid footprint with the English letters “WANTED Canis hodophilax.” The latin refers to the name Dutch zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck used nearly two centuries ago to describe the animal, also known as the Honshu wolf.

The rear window of Hiroshi Yagi's minivan | OSCAR BOYD

Dressed roughly in rubber sandals and a short-sleeve down jacket, Yagi briefly introduced himself while we drove toward the residence of Rina Kambayashi, a woman who claims to have seen a wolf in her garden in late 2018. He told me about the photographs he had taken in 1996 and explained that he ran a nonprofit organization dedicated to finding the supposedly extinct animal. I was immediately drawn to his light-hearted sense of humor, and found his tendency to ramble when the conversation turned to his lifelong passion a sign that he was the genuine article.

Since then, I’ve kept in close contact with him. I also met the members of his nonprofit group as they performed routine maintenance of the trail cameras Yagi had set up deep in the mountains of Okuchichibu in a bid to catch the wolf on film. In the meantime, I did my own homework on the history and folklore of the beast. The more I learned, the more I found myself intrigued by its mystique. I began to understand why Yagi had dedicated so much of his life to this search.

Soon after the encounter with the canine in the fall of 1996, Yagi sent his pictures to several experts. Most said the photographs were not enough to make a judgment on what exactly the animal was. The exception was the late Yoshinori Imaizumi, Japan’s leading mammalogist and former director of the National Museum of Nature and Science’s zoological department.

In December, a letter arrived at Yagi's home in Ageo, a suburban city in Saitama Prefecture. In the two-page type-written note, Imaizumi compared in detail the morphological characteristics of the beast Yagi had photographed with those of the wolf and yamainu (mountain dog) specimens acquired in Osaka by German naturalist Philipp Franz von Siebold in 1826 during his tenure in Dejima, Nagasaki Prefecture.

These specimens, including a mounted specimen of the yamainu, are currently in the collection of the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, the Netherlands. Collectively they are considered the Japanese wolf’s type specimen, meaning a specimen originally used to name a species or subspecies. These have also been a source of taxonomic confusion that I will attempt to explain in a latter installment of this series.

In the letter, Imaizumi listed 12 similarities between the canine Yagi photographed in the mountains of Chichibu and Siebold’s taxidermied specimen, including its short ears, black tail end, length, color and patterns of the fur, and a lack of the stop, or bulging frontal furrow found in dogs. Imaizumi named the animal the Chichibu yaken (Chichibu wild dog) and concluded the letter as follows:

“Setting aside what exactly a ‘Chichibu yaken’ is, it seems apparent that (the creature in the photographs) is a rare animal that could potentially be a surviving Japanese wolf and not some Husky wolf hybrid,” Imaizumi wrote. “The animal’s true identity can only be revealed with further research. I am hoping that you will put forth all your efforts in its investigation and protection.”

Imaizumi's letter cemented Yagi’s conviction that the extinct animal was still out there in the wild, waiting to be rediscovered. The skeptics — and there were many — only hardened his defiance, a rebellious streak rooted in his childhood.

A keen mountaineer, Hiroshi Yagi has climbed numerous peaks in search of the Japanese wolf. | COURTESY OF HIROSHI YAGI

Man of the mountains

Yagi was born on Nov. 15, 1949, in Uonuma, a city in Niigata Prefecture known for its nationally recognized crop, the koshihikari variety of rice. The youngest of five siblings, he was often left to play on his own as his parents busied themselves producing traditional local textiles known as Ojiya Chijimi.

“I was called tsuruttaguri,” he says. “In my hometown’s dialect that means the ‘last fruit on the vine,’ and implies you’re good for nothing.”

He spent much of his time at his neighbor’s farm in the mountains an hour on foot from his home.

“There was an old woman living next door who didn’t have children,” he says. “She took good care of me and I’d tag along when she went to tend her vegetables. That’s how I got my first taste of the mountains.”

In high school, Yagi joined the mountaineering club and would climb peaks including Mount Tanigawa, a 1,977-meter mountain on the border of Gunma and Niigata prefectures, as well as the 2,003-meter Mount Echigo-Komagatake, one of the three great Echigo mountains alongside Mount Hakkai and Mount Nakanodake.

After graduation, his love of the outdoors led him to join the now-defunct Kokudo, a real estate company that was part of the Seibu Group conglomerate. This was the late 1960s, when Japan was cruising on one of the most rapid economic growth trajectories the world has ever seen.

It was also a period when student movements flourished and industrial pollution resulting from massive manufacturing and construction demand became a hot topic. Vast swaths of forest were being razed and replanted with fast-growing conifers under a government-led campaign to procure lumber, policies that would leave an irreversible impact on the nation’s ecological landscape.

A world away from the sociopolitical developments then sweeping urban centers, Yagi was assigned to manage mountain huts on Mount Naeba, a 2,145-meter volcano on the border of Nagano and Niigata prefectures that Kokudo was planning to develop into a ski resort. A dream job for Yagi, it involved tending to the needs of climbers who sought shelter in the mountaintop Yusenkaku lodge and the Wadagoya hut sitting halfway up at 1,370 meters.

The incident that would change his life took place in the wee hours of July 29, 1969.

“It was the week after Neil Armstrong and his crew on Apollo 11 became the first men to walk on the moon,” he recalls.

At 11 p.m. on July 28, Yagi and another staff member left the mountaintop lodge for the Wadagoya hut, where they were to stock up on rice for a group of climbers scheduled to arrive at the peak in a few days’ time. The distance from one hut to the other was around 5 kilometers as the crow flies. The route typically took four hours to traverse, but the pair made it in half that time.

“We knew the path well, and a full moon was shining our way,” he says. They each collected 30 kilograms of rice and left Wadagoya at 1 a.m. to head back up to Yusenkaku.

An hour or so later, the pair stopped for a short break in a beechwood forest. As they lay on their backs, a roaring cry pierced the night.

“I was tired and dozing off,” he says. “The first howl was long, followed by another howl. I was fully awake by the third howl and was terrified. I woke the other guy up. We abandoned the rice where we were and rushed back down to Wadagoya.”

The July 29 entry in the diary he kept at the time is unusually succinct, reflecting how shaken he was. The entry simply says: “Beast howl.”

Yagi’s primal fear may have spared him from a serious accident. According to his initial plan, he was supposed to board a 10:30 a.m. bus leaving the entrance of Mount Naeba for Echigo-Yuzawa Station to buy groceries and other necessities. He missed the ride since he instead had to climb back up to Yusenkaku in the morning to deliver the rice he had left in the forest the previous night. Yagi would later learn that the bus slipped off a cliff. Seventeen passengers were injured.

“I felt protected by the wolf,” he says. “But I also knew no one would believe me if I said I had heard the cry of an animal that had gone extinct in the Meiji Era (1868-1912). I kept the incident to myself for the longest time.”

The events of that night in 1969 would linger in Yagi’s mind as life moved on. He would quit Kokudo after two years and work for an outdoor gear manufacturer before getting hired by Unimat, a vending machine operator.

He launched his own vending machine business when he was 35, by which time he was married with two children. His family had moved to the city of Ageo in Saitama Prefecture, and he began exploring the mountains of Chichibu and immersing himself in the region’s long history of wolf worship and frequent tales of modern-day sightings.

The Okuchichibu mountain range has been home to legends and folklore about the Japanese wolf, an animal that supposedly went extinct in 1905. | OSCAR BOYD

Wolf enthusiast

Fast forward to 1996, the year Yagi photographed the peculiar animal. By then, he was a well-known figure in the wolf enthusiasts’ community, with a solid track record as an independent researcher traveling across the nation to do fieldwork.

In 1995, he hosted the Japanese Wolf Forum at Mitsumine Shrine, the most prominent of Chichibu’s wolf-worshipping shrines. That same year, he had also discovered a suspected wolf pelt stored in the home of Chichibu resident Shigeru Uchida. Following careful analysis, the specimen would eventually become one of the world’s nine recognized remaining pelts of the Japanese wolf.

But it was the encounter in 1996 with what perhaps was a living relic that breathed fresh air into Yagi’s search for the lost beast.

He also had a new lead. A local hunter saw what was likely the same animal on Dec. 27, two months after Yagi documented his encounter. The distance between where the sightings took place was only a kilometer, convincing him that it was still roaming the area.

“If I couldn’t persuade the skeptics with photographs, the next step was to capture the animal on video,” Yagi says. This was before the age of smartphones. Pocket-sized digital cameras and camcorders were expensive. He purchased three video cameras for ¥1 million and had an acquaintance remodel them so they could weather the elements.

Assisting him in this venture was his friend, Tadashi Okada, a Kyoto-based sculptor of Buddhist statues. Upon learning about the second sighting, Okada hoisted his tent and sleeping bag onto his 50 cc motorbike and drove almost 500 kilometers to Chichibu.

Over the next year, Okada would spend a total of six months camping out in the Okuchichibu mountains. He was equipped with a military night vision telescope to monitor the landscape after nightfall.

“I would visit Okada once a week to deliver food, booze and gasoline for the household power generator he used to charge his motorcycle battery hooked up to the video cams,” Yagi recalls.

The method, unfortunately, didn’t yield any results. To make matters worse, Okada was severely injured when, weighed down by his gear, he fell off a cliff and broke his thigh — an accident that hospitalized him for six months. The extremities to which Okada and Yagi went in pursuance of the canine, however, became known by word of mouth and they began receiving reports of sightings and howls.

“I mean, who else would spend half a year in the mountains searching for an animal that shouldn’t even exist?” Yagi says.

It was around that time that Yagi began using trail cameras equipped with passive infrared motion detectors, which react and record whenever an animal enters the field of view. It was a fortuitous discovery that would allow him to monitor multiple locations without having to be physically present, and this remains the primary device he uses in collecting footage.

Yagi and his NPO have installed about 70 trail cameras in the Okuchichibu mountains. | THOMAS DELSOL / HANS LUCAS

While Yagi was experimenting with various technological gadgets in the mountains of Chichibu, another series of photographs taken 1,000 kilometers away splashed across headlines and poured fresh fuel on the still-glowing embers of the debate over the existence of the Japanese wolf.

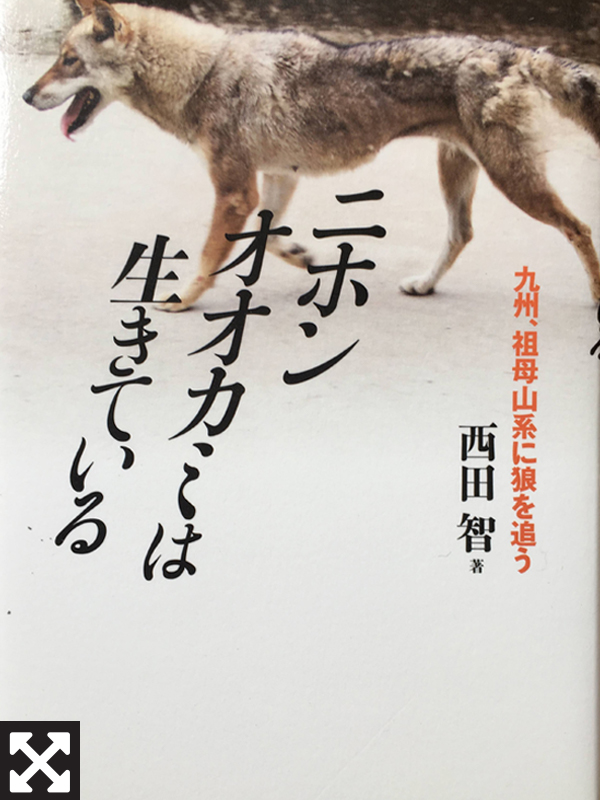

On the evening of July 8, 2000, high school principal Satoshi Nishida was camping out at the base of Mount Katamuki, part of the Sobo Katamuki Mountain range covering Oita and Miyazaki prefectures. He had been exploring mountain paths in search of traces of the moon bear, an animal considered to have gone extinct on the island of Kyushu in the 1950s.

While he was relaxing, can of beer in hand, he saw a lone, dog-like animal approaching the resting area and trotting toward the parking lot. Nishida thought it must be a feral dog but he fetched his camera anyway and shot a total of 10 photographs. He was startled when he saw the developed images two days later. The medium-sized animal had a mostly gray-and-black coat with shades of orange on its legs and behind its ears. It’s tail was straight and stubby, it had short ears, a thin waist and a flat, triangular forehead.

“This isn’t a dog,” he recalls thinking at the time, according to his book “Nihon Okami wa Ikiteiru” (“The Japanese Wolf is Alive”).

Excited, Nishida sent the photographs to experts, including Imaizumi, who said the animal resembled the Japanese wolf type specimen and named it the Sobo yaken in reference to where it was filmed. There were others, however, who claimed the canine appeared to be a wild Shikoku, a Japanese breed of dog. The subsequent media circus and occasional slanderous comments targeting Nishida gradually forced the high school principal to distance himself from the public eye.

“Mr. Nishida became media shy, so I thought it was my duty to continue exposing myself to criticism while gathering information,” Yagi says. In 2010, Yagi launched his NPO and began writing blog entries in earnest, introducing his own research to date and the reports of both old and new purported wolf sightings he had accumulated over the years.

“The impact of the blog was immense,” he says. “Many other people began coming forward to share their stories.”

Multiple sightings

In 2012, public broadcaster NHK ran a 50-minute documentary titled “Kenroki,” focusing on Yagi’s saga and wolf mythology. Hiroyuki Yoshimura happened to be watching the show, and was transfixed by the photos of the Chichibu yaken.

“Until then I didn’t even know that the Japanese wolf had been extinct, but the photographs and the possibility that it might still be alive was exhilarating,” Yoshimura says. “I wanted to do something to help out, and immediately contacted Yagi and found out he lived in a neighboring city.”

Yoshimura, a pest control specialist by day, soon began accompanying Yagi on his weekly trips to Okuchichibu. The tedious routine involves exchanging batteries and data cards from a few of the 70 or so camera traps mounted in areas with reports of sightings.

As Yagi likes to say, “it’s about connecting the dots.”

“One spontaneous sighting may not amount to much,” he says, “but if there are multiple sightings in the same area, there’s a much higher probability that we may be able to capture worthwhile footage.”

And sometimes having good ears can lead to unexpected discoveries. One night in late 2018, Yoshimura was at his home reviewing a short clip recorded on the morning of Oct. 21 that showed three deer running toward the camera.

He thought he heard something unusual, and asked if it was coming from the television show his son was watching.

“My son said, ‘no,’ so I rewound the footage several more times and found that it had picked up the sound of a howl.”

Yagi took the recording to the Japan Acoustics Lab in Tokyo, which concluded that the fundamental frequency of the howl was nearly identical to a sample howl of a timber wolf recorded at Asahiyama Zoo, Hokkaido. The Japan Times reported this finding after Yagi informed me of the development, and it was then featured in a segment that ran on broadcaster TV Asahi’s Sunday Station news program on Dec. 8, 2019.

“I felt I was finally able to contribute something to Yagi’s search,” Yoshimura says.

Others jumped on the bandwagon after personal encounters with the unthinkable. Misako Yokoyama, a tanned, cheerful handywoman based in Chiba Prefecture, was climbing toward Mitsumine Shrine’s okumiya (remote shrine) that sits atop Mount Myohogatake when she heard successive howls.

“I remember it clearly,” Yokoyama recalls. “It was April 23, 2014, at around 1 p.m. There was still some snow remaining on the mountain path. As I was ascending, I heard the cry.”

At this point, Yokoyama says she was unaware that the Japanese wolf was supposedly extinct.

“I heard the howl five or six times. After returning home, I went online to find out what it was coming from. I even listened to the cry of a llama for comparison,” she laughs. “The closest I came to was the howl of a wolf.”

A couple of years later, Yokoyama discovered a Facebook group page run by one of Yagi’s acquaintances and posted her own experience. Yagi reached out and she, along with her hiking buddy and work boss Ryosuke Sarashi, met Yagi in Chichibu late in 2018.

“We joined Yagi on a routine trail camera maintenance trip in the mountains, and he convinced us to buy our own cameras and to set them up near where Yokoyama heard the howls,” Sarashi says. The pair soon purchased the devices and now maintain 10 camera traps mounted on trees near the sacred path leading up to the okumiya.

Running out of time?

Yagi turned 71 in November. While he is fit and sprightly for a septuagenarian, he doesn’t deny that his age is catching up with him. He no longer embarks on days-long treks as he had done when he was younger. He tells me that maintaining the 70 or so trail cameras and reviewing the accumulated footage is his physical limit. Yoshimura, his protege, knows where the cameras are strapped in case he can no longer tend to them himself.

His faith in the wolf’s existence, however, has never faltered.

“What can you believe in in this world if you can’t believe in your own experience?” he asks. “That wolf howl 50 years ago on Mount Naeba and the 1996 photos of the Chichibu yaken has convinced me that I’ve been chosen by the gods, if there are such beings, to find the Japanese wolf.”

Yagi’s goal is to secure major sponsors, such as national broadcaster NHK or a wealthy foundation, to fund the search. He knows that photographs and even video footage aren’t the definitive proof he needs to convince the public of the Japanese wolf’s existence. Substantial investments in technology will significantly improve the chances of finding the beast.

“Ultimately, we want to shelter and protect the rare animal,” he says, adding that it has always been the naysayers who mock his pursuit that have fueled his drive.

“They can say all they want to,” he says, “but I know from experience that you need to get up from your desk and go out into the field to find the truth.”

Yagi has accumulated a vast trove of anecdotes, data and literature related to the Japanese wolf over the past half century. But no matter how much he learns, he says there are always fresh discoveries that open new windows into the understanding of the mysterious beast.

Even now, researchers are exploring the animal’s ancient origins and relationship with humans, while DNA analysis is helping untangle its ambiguous taxonomic identity that some describe as one of Japan’s most compelling zoological riddles.

Meanwhile, Yagi is onto a new lead. He is in possession of dashcam footage taken past midnight on Aug. 4, 2019, by a man who was driving on route 278, a winding mountain road that connects Mitsumine Shrine to route 140 leading to the city of Chichibu. On the video, a silhouetted canid can be seen crossing the road and walking under the guardrails to the left, disappearing into the bushes, just as the Chichibu yaken had 25 years ago.

Yagi has camera traps mounted in the vicinity now, one of which he showed me during a trip to Mitsumine Shrine in August last year.

“This is an area with multiple reported cases of sightings,” he explains as he checks the trail cam’s memory card. “Let’s see what we find.”

Dashcam footage from Aug. 4, 2019, on Route 278, a mountain road that connects Mitsumine Shrine to the city of Chichibu.