MATT SCHLEY

Contributing writer

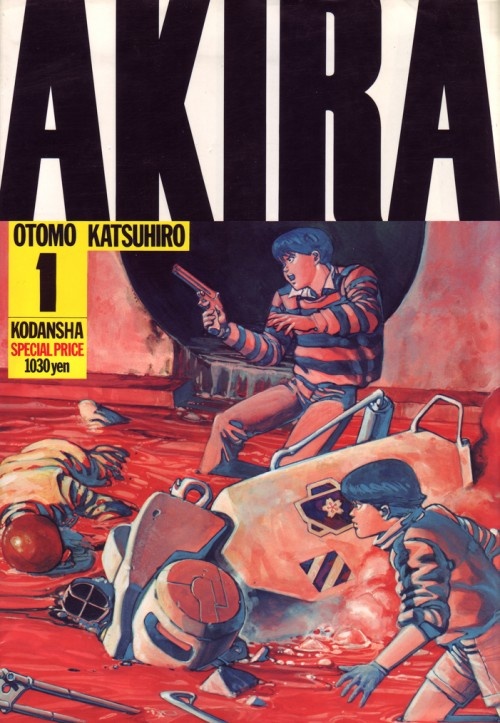

The cyberpunk comic “Akira” was the creation of Katsuhiro Otomo, whose manga, “Domu,” one of Weekly Young Magazine’s first series, featured children with dangerous psychic powers. “Akira” expanded that idea onto a much larger canvas — a post-World War III Neo-Tokyo — that was populated with revolutionaries, rioters, corrupt politicians, drug dealers and biker gangs.

For many readers, “Akira” was a revelation. Each panel features a head-spinning amount of detail, and Otomo, an avowed film buff, keeps things moving at a breathless, cinematic pace. Comic writer Warren Ellis once called the manga

“a headlong, super-adrenalized SF (sci-fi) adventure story that reinvented the term ‘property damage.’”

Still, “Akira” is about more than just superpowers and spectacle. Influential postwar science fiction manga like “Tetsuwan Atomu” (also known as “Astro Boy”) depict a bright future in which technology leads to prosperity, but “Akira” (which debuted the same year as “Blade Runner”) features a darker, more dystopian vision. In Otomo’s future, technology runs wild, turning Tokyo into an uncontrollable, overgrown mass that spawns class division and disaffection. The city may be filled with giant, glittering skyscrapers, but the majority of its citizens, including the story’s biker antiheroes, cannot afford to set foot in them.

In many ways, Otomo’s dystopian future is a reflection of the recent past: specifically Japan’s left-wing student movement, which fizzled out when the artist was in his teens.

“Otomo jacked into his generation’s frustration with society, in the wake of the defeat of Japan’s liberal student movement, and created an epic that, in true Japanese fashion, processed societal trauma through cataclysmic visual symbolism,” says Kodansha USA’s Naho Yamada.

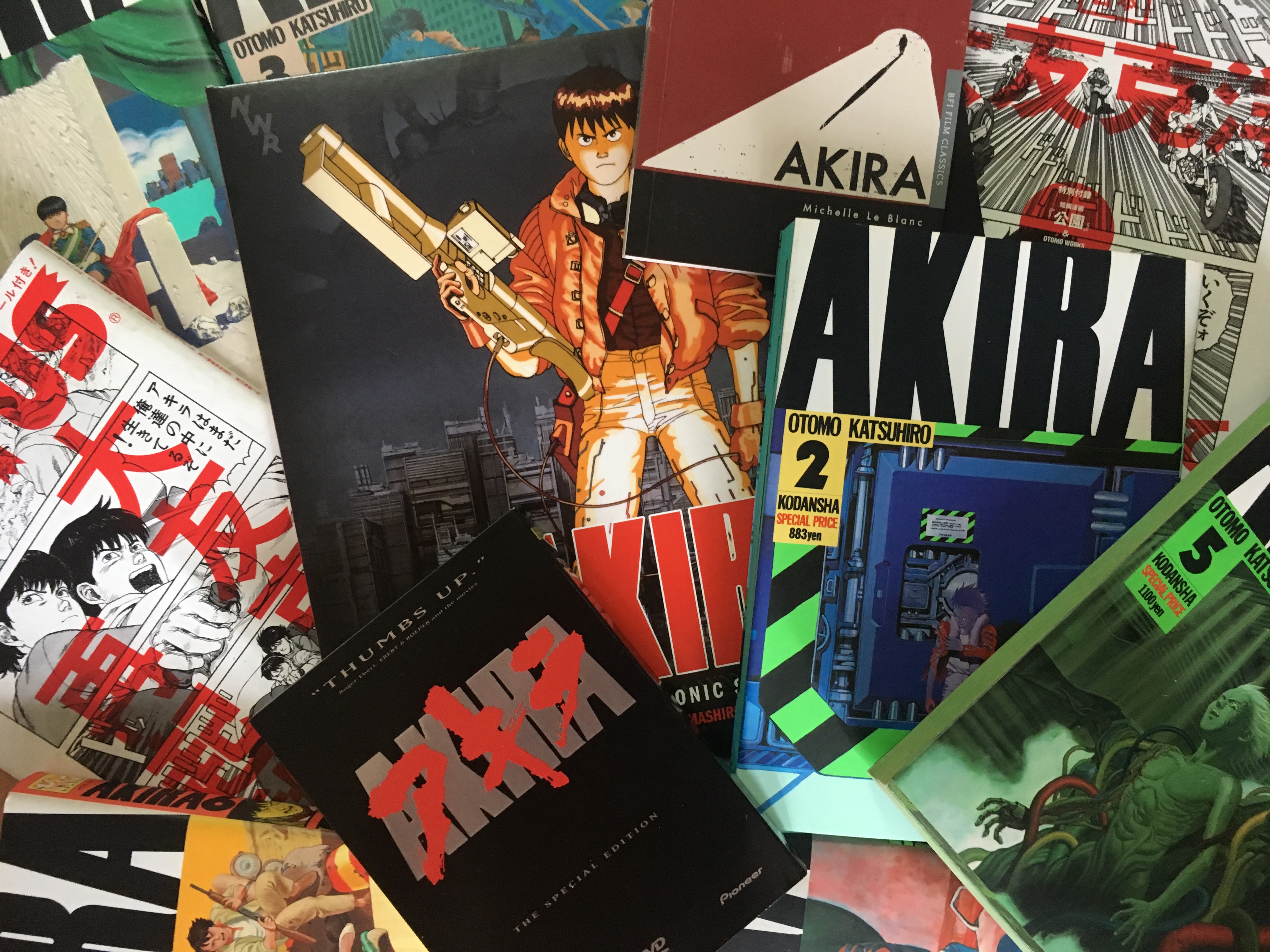

Otomo’s combination of visual spectacle and thought-provoking themes proved a hit. The manga ran for eight years, won awards like the Kodansha Manga Award and the Harvey Award, and prompted the creation of an animated feature film in 1988, also helmed by Otomo.

That was also the year that the “Akira” manga first left Japan’s shores for the West. Released by Epic Comics, a Marvel Comics imprint, “Akira” was one of the first manga published in English. In a 1988 interview, editor Archie Goodwin explained, “Mr. Otomo’s story seemed to fit what I thought were the tastes of the American audience.” These included psychic powers and a sci-fi setting, both elements with which American readers were already intimately familiar.

To better fit the American market, Epic also split “Akira’s” phone book-sized volumes into smaller chunks and recruited colorist Steve Oliff to paint each page of the manga. Otomo visited Oliff in his hometown of Point Arena, California, where they bonded over Jack Daniel’s and discussed what the manga’s black-and-white pages should look like in color.

“Akira” was painted digitally — a revolutionary step at the time — on a PC with a 12 megahertz processor and a handmade heat diffuser that, Oliff wrote, “chugged like an old farm truck.” Initially, the colorist sent drafts to Otomo for approval, but eventually, the “Akira” creator told Oliff he trusted him with it completely. In an interesting cross-cultural moment, Epic’s colorized version was converted back into Japanese and released in Japan soon thereafter.

By the early 2000s, the word “manga” had entered the English lexicon, and readers had become aware that these Japanese comics came in black and white. That prompted Dark Horse Comics president Mike Richardson — who had actually wanted to release “Akira” back in the 1980s — to snap up the U.S. rights and publish the manga in its original, un-colorized form.

“Despite the doubts of some, who felt its time had passed,” wrote Richardson in 2009, “the series was a tremendous success.”

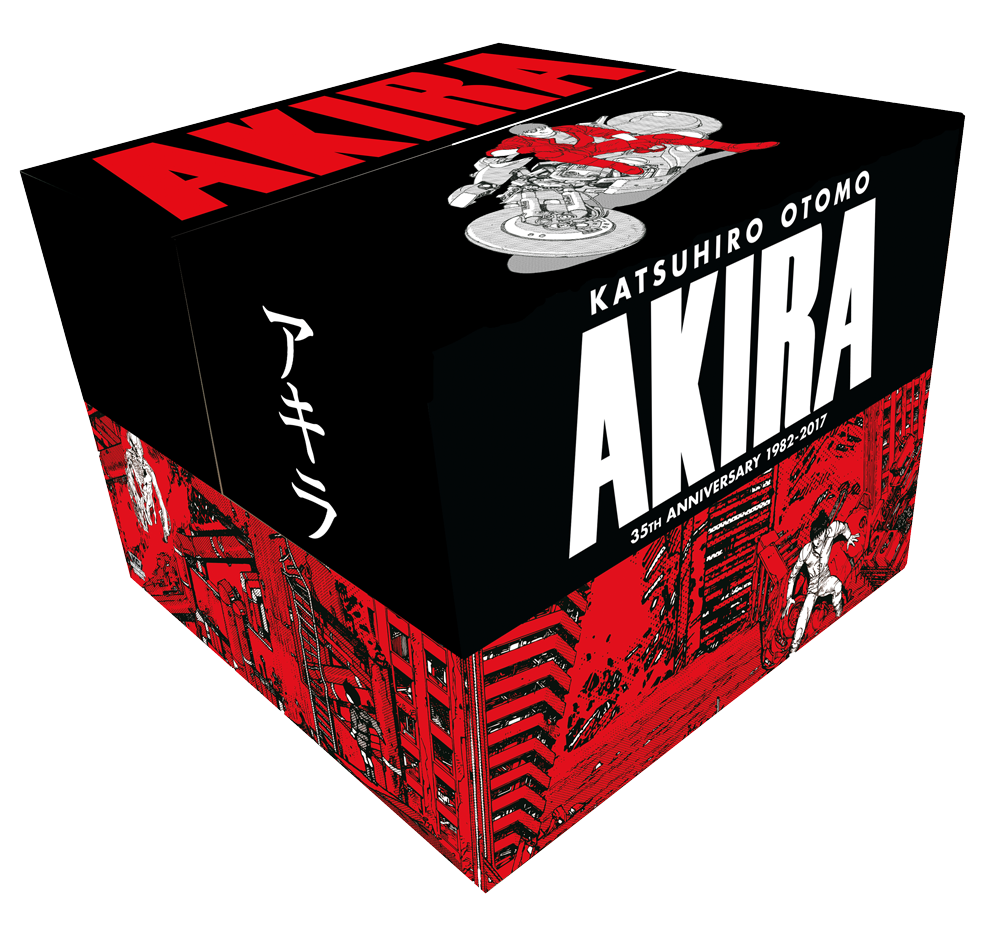

That remains the case almost a decade later. Last year’s U.S. rerelease of the manga, a 35th anniversary box set published by Kodansha Comics, was, in dollar terms, the best-selling manga of 2017.

That remains the case almost a decade later. Last year’s U.S. rerelease of the manga, a 35th anniversary box set published by Kodansha Comics, was, in dollar terms, the best-selling manga of 2017.

“The demand for ‘Akira’ in the English-speaking world has been constant and unwavering for decades, in a way that no other manga has matched,” says Ben Applegate of Penguin Random House Publisher Services for Kodansha Comics. “Its success is an illustration of how fundamental ‘Akira’ is to modern popular culture.”

Taking the authenticity of the Dark Horse Comics release one step further, Kodansha’s new release is “unflipped,” read right-to-left like the original Japanese release, and features Otomo’s original hand-drawn sound effects.

“When you read Otomo’s work, you can feel the intentionality behind each stroke, like the work of a great calligrapher, and the sound effects are an important part of that,” says Applegate.

In addition to the English-speaking world, “Akira” has been released in over 50 countries, including in France, where Otomo has been made an Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters.

“‘Akira’ ignited a new generation of dynamism not only in manga but also in European and American comics,” says Yamada. “Its impact shattered all borders.”

Read all #AkiraWeek articles

-

Akira: Looking back at the future‘Akira’: Looking back at the futureOn the 30th anniversary of the release of ‘Akira’ in Japan, we examine the enduring...

Akira: Looking back at the future‘Akira’: Looking back at the futureOn the 30th anniversary of the release of ‘Akira’ in Japan, we examine the enduring... -

Speak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkSpeak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkWant to give your nihongo a bit of biker edge? Let Neo-Tokyo be your...

Speak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkSpeak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkWant to give your nihongo a bit of biker edge? Let Neo-Tokyo be your... -

'Akira' inspires generations of foreign animators‘Akira’ inspires generations of foreign animators‘Why did you come to Japan?’ For many people, the answer is Katsuhiro Otomo‘s visionary...

'Akira' inspires generations of foreign animators‘Akira’ inspires generations of foreign animators‘Why did you come to Japan?’ For many people, the answer is Katsuhiro Otomo‘s visionary... -

'Akira' soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpiece‘Akira’ soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpieceGeinoh Yamashirogumi's epic soundscape still resonating with musicians and listeners decades later

'Akira' soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpiece‘Akira’ soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpieceGeinoh Yamashirogumi's epic soundscape still resonating with musicians and listeners decades later -

Do you remember the first time you watched 'Akira'?Views from the street: TokyoDo you remember the first time you watched ‘Akira’?

Do you remember the first time you watched 'Akira'?Views from the street: TokyoDo you remember the first time you watched ‘Akira’? -

The enduring appeal of 'Akira,' the mangaThe enduring appeal of ‘Akira,’ the mangaThroughout multiple English-language incarnations of the cyberpunk classic, demand has never wavered

The enduring appeal of 'Akira,' the mangaThe enduring appeal of ‘Akira,’ the mangaThroughout multiple English-language incarnations of the cyberpunk classic, demand has never wavered -

The pain and the passion that fueled the creation of 'Akira'The pain and passion that fueled ‘Akira’For many of the animators who toiled to bring Neo-Tokyo to life, it was a...

The pain and the passion that fueled the creation of 'Akira'The pain and passion that fueled ‘Akira’For many of the animators who toiled to bring Neo-Tokyo to life, it was a... -

Collecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeCollecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeHow Joe Peacock became the owner of the world’s largest collection of ‘Akira’ cels.

Collecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeCollecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeHow Joe Peacock became the owner of the world’s largest collection of ‘Akira’ cels. -

My deep dive into 'Akira' only scratched the surface of its legacyMy deep dive into ‘Akira’ only scratched the surface of its legacyA few months ago, I proposed to the editors at The Japan Times that we...

My deep dive into 'Akira' only scratched the surface of its legacyMy deep dive into ‘Akira’ only scratched the surface of its legacyA few months ago, I proposed to the editors at The Japan Times that we...