MATT SCHLEY

Contributing writer

“Akira,” the legendary anime film from 1988, marks its 30周年 (sanjusshunen, 30th anniversary) this week.

That film, and the manga that inspired it, are set in the far-flung year of 2019, when Tokyo has been destroyed by a 新型爆弾 (shingata bakudan, new type of bomb) that started 第三次世界大戦 (Daisanji Sekai Taisen, World War III). Rebuilt as the dystopian ネオ東京 (Neo-Tokyo), the megalopolis is populated by corrupt politicians, revolutionaries, 超能力者 (chōnōryokusha, those with psychic powers) and teenage 暴走族 (bōsōzoku, motorcycle gangs).

Those studying Japanese in the classroom tend to learn very polite forms, phrases and conjugations, which makes sense — no teacher wants their students to go out into the world sounding like 不良 (furyō, good-for-nothings). But those looking to give their Japanese a bit of biker edge (or simply better understand what the furyō in anime and manga are actually saying) while simultaneously taking in an epic sci-fi tale could do worse than a screening of “Akira.”

Both the manga and movie start by introducing us to a gang of bōsōzoku led by main character Kaneda and his best friend (and eventual super-villain) Tetsuo. Both had a hard childhood, growing up in a 孤児院 (koji’in, orphanage). The smaller of the two, Tetsuo often faced いじめ (ijime, bullying) until Kaneda came to the rescue, leaving Tetsuo with a serious inferiority complex that plays a major role in the story.

Fast-forward a decade or so, and both have become hard-talking bikers — with a font of vocabulary you wouldn’t want to use in polite company. More often than not, the gang’s verbs end in ぜ (ze), which adds emphasis like よ (yo), but in a way generally considered more macho. Another classic method Katsuhiro Otomo uses to make his characters sound rough around the edges is by having them pronounce words that, in the dictionary, end in an い (i) with an えー (ē) instead. 知らない (shiranai, I don’t know) becomes 知らねー (shiranē), じゃない (ja nai, not) turns into じゃねー (ja nē), etc.

Like many rough anime characters, Kaneda and crew are also big fans of やがる (yagaru), which is added after the 連用形 (renyōkei, conjunctive form) of a verb, and often conjugated to やがって(yagatte) to express disbelief or anger.

The most common form of this compound combines する (suru, to do) with やがる to form しやがって (shiyagatte), meaning something like “How dare you?” But やがる can be used with any verb, really: For example, take a scene from the manga in which Kaneda chases the mysterious Takashi down an alleyway, adding やがる to なめる (nameru, underestimate) to form なめやがって! (Nameyagatte!, How dare you underestimate me!).

The most common form of this compound combines する (suru, to do) with やがる to form しやがって (shiyagatte), meaning something like “How dare you?” But やがる can be used with any verb, really: For example, take a scene from the manga in which Kaneda chases the mysterious Takashi down an alleyway, adding やがる to なめる (nameru, underestimate) to form なめやがって! (Nameyagatte!, How dare you underestimate me!).

Punks they may be, but bōsōzoku aren’t without their own set of social rules, and when it comes to the gang in “Akira,” there’s a very clear pecking order — with Kaneda on top. As Tetsuo’s psychic powers grow (and his ego grows along with them), we see an interesting use of honorifics come into play. Tetsuo begins to refer to Kaneda as 金ちゃん (Kane-chan), using the diminutive chan meant for children, especially girls. Kaneda, suffice it to say, is not a fan of this 口のきき方 (kuchi no kikikata, way of speaking). During their final battle, Kaneda attempts to regain respect by yelling at Tetsuo: さんを付ける! (San o tsukeru!, Use “san”!). Or, in other words, “That’s Mr. Kaneda to you!”

Speaking of pecking order, “Akira” gives us lots of nice rough ways to give someone an order. The standard way to ask or tell someone to do something is to conjugate to て (te) form, also known as continuative form. But there are other forms you can use to add a biker punk edge to your orders. Take, for example, the gruff owner of the bar that appears in the film’s opening sequence. Surprised by Yamagata’s sudden entrance, he yells 静かに開けよう (Shizuka ni akeyō, Open [the door] quietly), conjugating 開ける (akeru, open) to volitional form to add emphasis to his command.

An example of how to roughly tell someone not to do something, on the other hand, can be heard when a group of hospital guards moves in to subdue Tetsuo (man, they have no idea what they’re in for). Tetsuo doesn’t want them to come any closer, but he’s too cool to use the wimpy, normal negative te form, 来ないで (Konai de, Stay away). Instead, he shouts 来るんじゃねー! (Kuru-n ja nē!, Stay the hell away!), which combines the regular form of kuru with a nice bōsōzoku-y version of ja nai, plus an n in there to join them together.

An example of how to roughly tell someone not to do something, on the other hand, can be heard when a group of hospital guards moves in to subdue Tetsuo (man, they have no idea what they’re in for). Tetsuo doesn’t want them to come any closer, but he’s too cool to use the wimpy, normal negative te form, 来ないで (Konai de, Stay away). Instead, he shouts 来るんじゃねー! (Kuru-n ja nē!, Stay the hell away!), which combines the regular form of kuru with a nice bōsōzoku-y version of ja nai, plus an n in there to join them together.

“Akira” may be set in the 近未来 (kin-mirai, near future) but it is a product of the 1980s, after all, and some of the vocabulary used by its main characters is distinctly dated. Here’s Kaneda explaining the fall Tetsuo takes from his motorcycle that kicks off the whole story:

驚いて鉄雄がチョンボしたんだよ (Odoroite Tetsuo ga chonbo shita-n da yo; Surprised, Tetsuo messed up [and fell]).

The word we’re interested here is the one for “messed up,” (i.e., made an error): チョンボ (chonbo). According to online dictionary zokugo-dict.com, this word came into general use in 1979, and apparently originated from the world of 麻雀 (mājan, mahjong).

OK, so we don’t use words like chonbo here in the late 2010s, but Otomo was extremely prescient on other counts. After all, how many manga and anime from the ’80s feature the 2020年東京オリンピック会場建設地 (2020-nen Tōkyō Orinpikku Kaijō Kensetsuchi, Tokyo Olympic Stadium construction grounds)?

Read all #AkiraWeek articles

-

Akira: Looking back at the future‘Akira’: Looking back at the futureOn the 30th anniversary of the release of ‘Akira’ in Japan, we examine the enduring...

Akira: Looking back at the future‘Akira’: Looking back at the futureOn the 30th anniversary of the release of ‘Akira’ in Japan, we examine the enduring... -

Speak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkSpeak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkWant to give your nihongo a bit of biker edge? Let Neo-Tokyo be your...

Speak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkSpeak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkWant to give your nihongo a bit of biker edge? Let Neo-Tokyo be your... -

'Akira' inspires generations of foreign animators‘Akira’ inspires generations of foreign animators‘Why did you come to Japan?’ For many people, the answer is Katsuhiro Otomo‘s visionary...

'Akira' inspires generations of foreign animators‘Akira’ inspires generations of foreign animators‘Why did you come to Japan?’ For many people, the answer is Katsuhiro Otomo‘s visionary... -

'Akira' soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpiece‘Akira’ soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpieceGeinoh Yamashirogumi's epic soundscape still resonating with musicians and listeners decades later

'Akira' soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpiece‘Akira’ soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpieceGeinoh Yamashirogumi's epic soundscape still resonating with musicians and listeners decades later -

Do you remember the first time you watched 'Akira'?Views from the street: TokyoDo you remember the first time you watched ‘Akira’?

Do you remember the first time you watched 'Akira'?Views from the street: TokyoDo you remember the first time you watched ‘Akira’? -

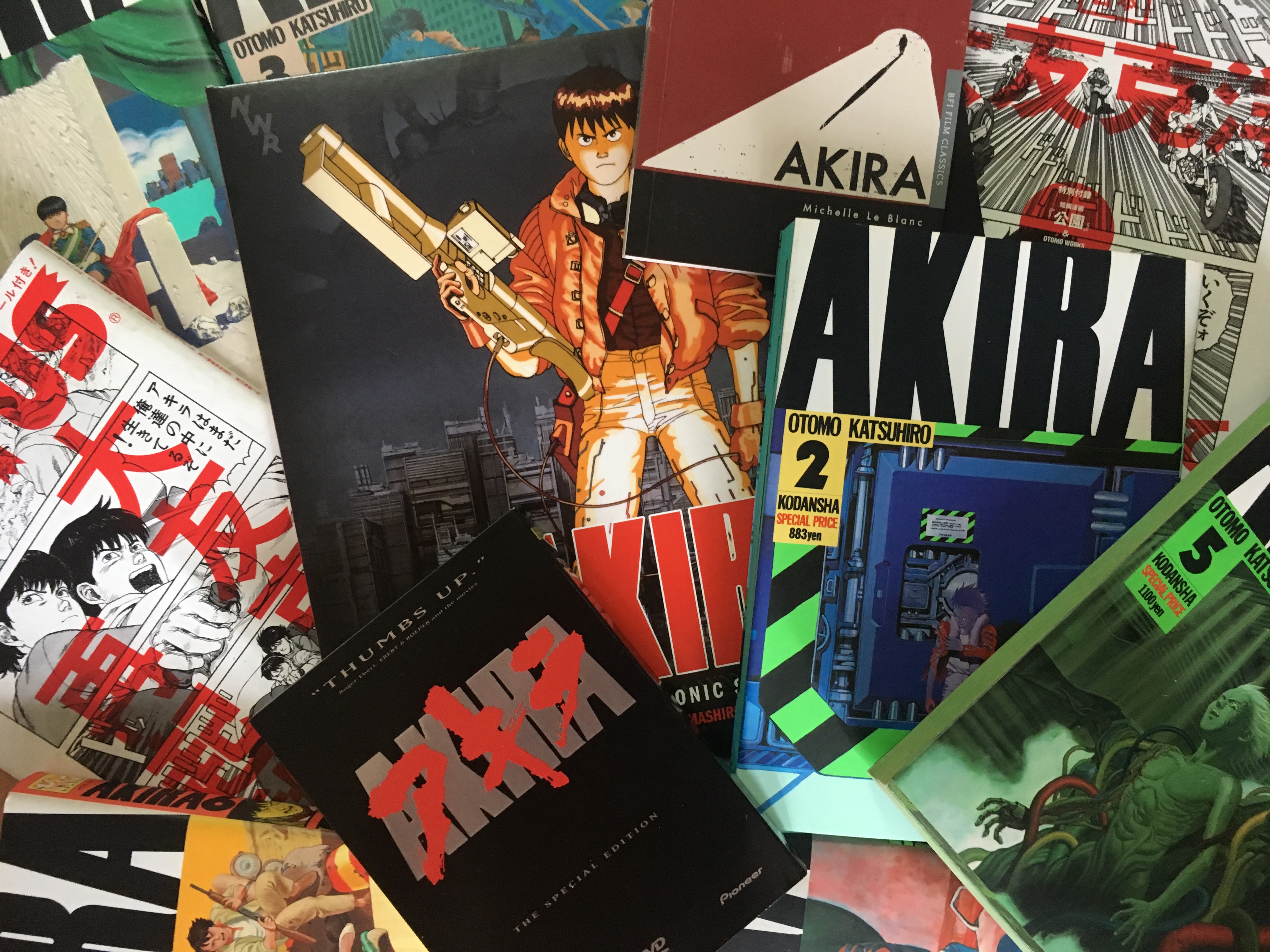

The enduring appeal of 'Akira,' the mangaThe enduring appeal of ‘Akira,’ the mangaThroughout multiple English-language incarnations of the cyberpunk classic, demand has never wavered

The enduring appeal of 'Akira,' the mangaThe enduring appeal of ‘Akira,’ the mangaThroughout multiple English-language incarnations of the cyberpunk classic, demand has never wavered -

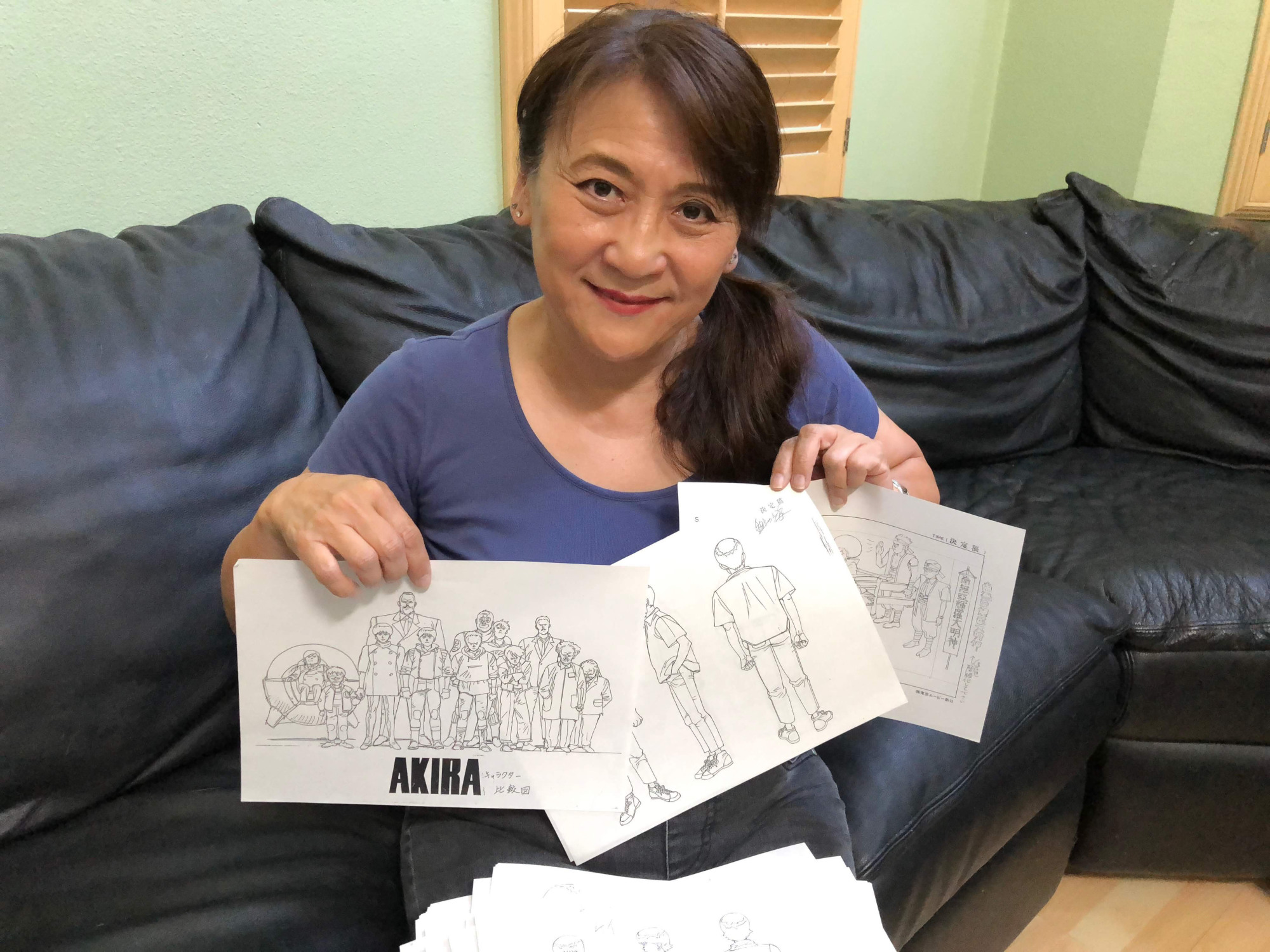

The pain and the passion that fueled the creation of 'Akira'The pain and passion that fueled ‘Akira’For many of the animators who toiled to bring Neo-Tokyo to life, it was a...

The pain and the passion that fueled the creation of 'Akira'The pain and passion that fueled ‘Akira’For many of the animators who toiled to bring Neo-Tokyo to life, it was a... -

Collecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeCollecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeHow Joe Peacock became the owner of the world’s largest collection of ‘Akira’ cels.

Collecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeCollecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeHow Joe Peacock became the owner of the world’s largest collection of ‘Akira’ cels. -

My deep dive into 'Akira' only scratched the surface of its legacyMy deep dive into ‘Akira’ only scratched the surface of its legacyA few months ago, I proposed to the editors at The Japan Times that we...

My deep dive into 'Akira' only scratched the surface of its legacyMy deep dive into ‘Akira’ only scratched the surface of its legacyA few months ago, I proposed to the editors at The Japan Times that we...