MATT SCHLEY

Contributing writer

“Akira” begins with a giant flash of light, signaling an explosion that decimates 1980s Tokyo and starts World War III. The film then jumps forward to 2019, a year in which the metropolis has rebuilt itself as Neo-Tokyo and is preparing to host the Olympics (sound familiar?).

Back in the real world, “Akira” set off an explosion of another kind. The movie, which hit domestic cinemas in July 1988, inspired a generation of creators in Japan and helped jump-start an appreciation of anime in the West. Much like its porous antagonist Tetsuo, “Akira” has seeped into every pop culture crack imaginable: from dance music to top streetwear brands to the Steven Spielberg film “Ready Player One.”

At the same time, “Akira” can probably best be described as a singular, unrepeatable phenomenon that was made at a time when ambition and budgets in the Japanese animation industry were at an unprecedented high.

Three decades after the release of the film, with a distinctly un-cyberpunk 2019 looming on the horizon, it’s worth asking why we’re still talking about “Akira” and what it all means today.

Birth of a classic

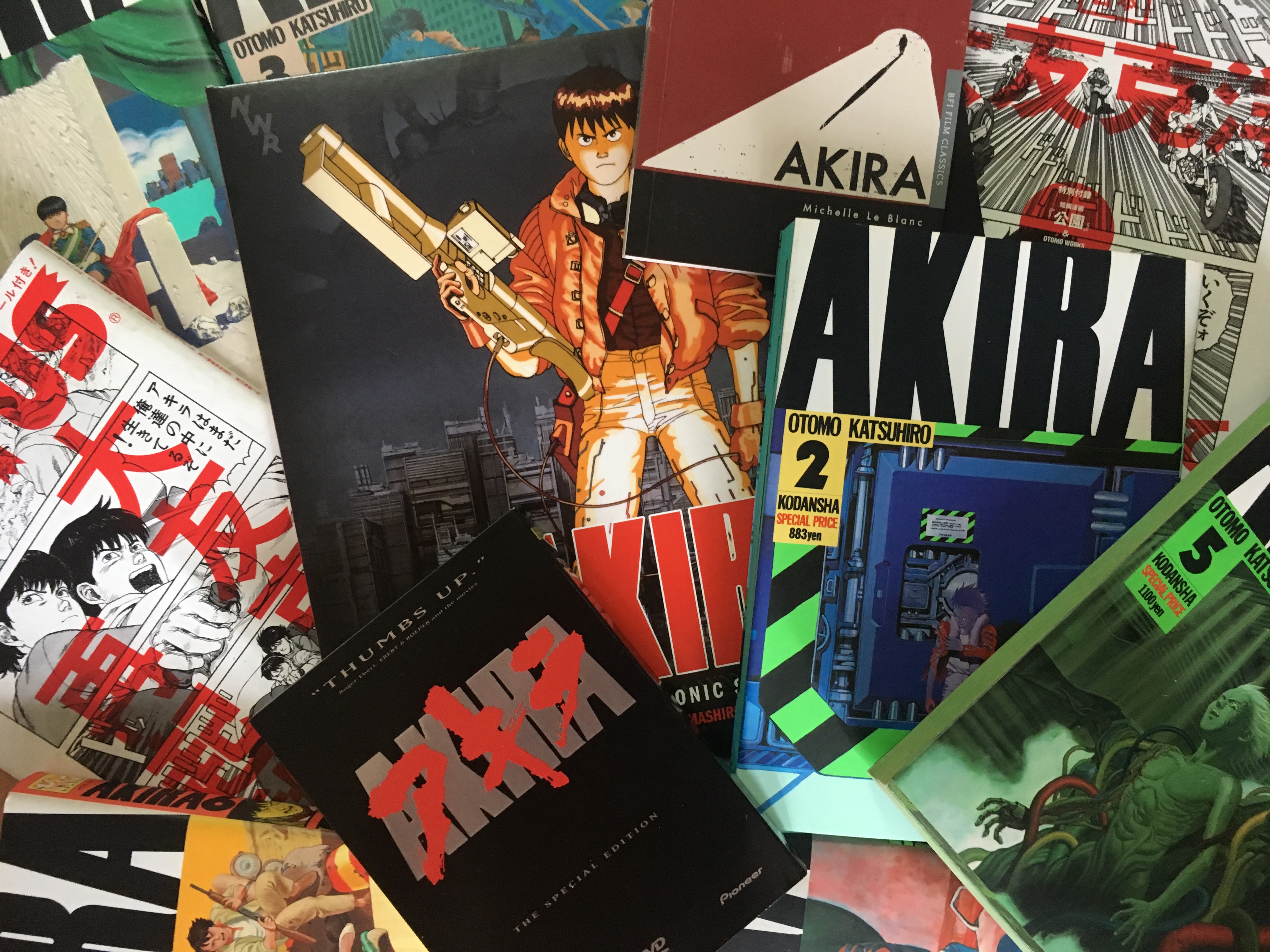

“Akira” was first born in December 1982 as a serialized manga in the pages of Kodansha’s Young Magazine. It was created by Katsuhiro Otomo, a native of Tome, Miyagi Prefecture, who made his debut as a manga writer and illustrator in 1973.

It ended up becoming Otomo’s magnum opus, running for eight years and filling six phone book-sized volumes. However, the themes that dominated the original manga were also present in the author’s earlier works, such as “Fireball” and “Domu,” which featured dystopian cities, revolutionaries, motorcycle punks and psychic powers. Like “Akira,” those earlier works also featured incredibly intricate penciling and cinematic pacing.

Set in 2019 in the dystopian city of Neo-Tokyo, “Akira” centers around a motorcycle gang who become involved in the fate of the city itself when one member, Tetsuo, has a run-in with a strange boy who wields psychic powers. This encounter activates a latent power within Tetsuo: a power dangerously close to that once wielded by Akira, a child who, rumor has it, had something to do with the destruction of the city and start of World War III.

“Akira” was a hit with the readers of Young Magazine. Within a few years of the manga’s serialization, it was decided that Otomo’s work would become an animated feature film — and not just any feature film. “Akira” was granted the largest budget of any anime movie up to that point — more than ¥1 billion.

A 1988 interview records Otomo as being fairly nonchalant about how the film came together, saying, “I’d done some animation before and know some people in the industry, so I figured, why not try to make it into an animation?”

In reality, putting together the most expensive anime film ever made was considerably more difficult than than he made it sound. No single company had the financial resources, nor manpower, to create a project on the scale of “Akira.” Instead, several firms, including publisher Kodansha, distributor Toho and anime studio TMS, teamed up to form what they called the Akira Committee. (The practice of dividing budget and risk in anime productions via so-called production committees is now standard throughout the anime industry.)

The committee may have supplied the funding, but “Akira” remained, creatively speaking, in Otomo’s hands. The manga author, who had directed only two animated shorts before helming the film, served as its director and co-screenwriter, and all aspects of the production flowed through him.

“‘Akira’ was so much Otomo’s movie, imbued with his voice and his passion, that it spoke to a whole generation with the same concerns,” says Helen McCarthy, co-author of “The Anime Encyclopedia.”

The production of the film brought together some of the most talented animators in the business, including Koji Morimoto, Hiroyuki Okiura, Toshiyuki Inoue and Takashi Nakamura — names that still activate the salivary glands of many anime fans today.

Kaneda on his bike in the opening chase scene in the anime "AKIRA" © 1988 MASH•ROOM / AKIRA COMMITTEE All Rights Reserved.

In the 1960s, Osamu Tezuka, who created “Tetsuwan Atomu” (also known as “Astro Boy”) laid down the template that Japanese animation productions by and large still follow: Unable to compete with animation giant Disney and other players in terms of budget, anime studios were forced to employ “limited animation” in which illustrators would produce less realistic, more stylistic animation with lower frame rates to save time and money.

However, “Akira” would be different. The massive budget afforded the crew luxuries rarely used in the history of Japanese animation, including pre-recorded voice acting for syllable-perfect lip synchronization, the early use of basic computer-generated imagery and, most importantly, a massive frame count that gave the film a fluidity that was anything but limited.

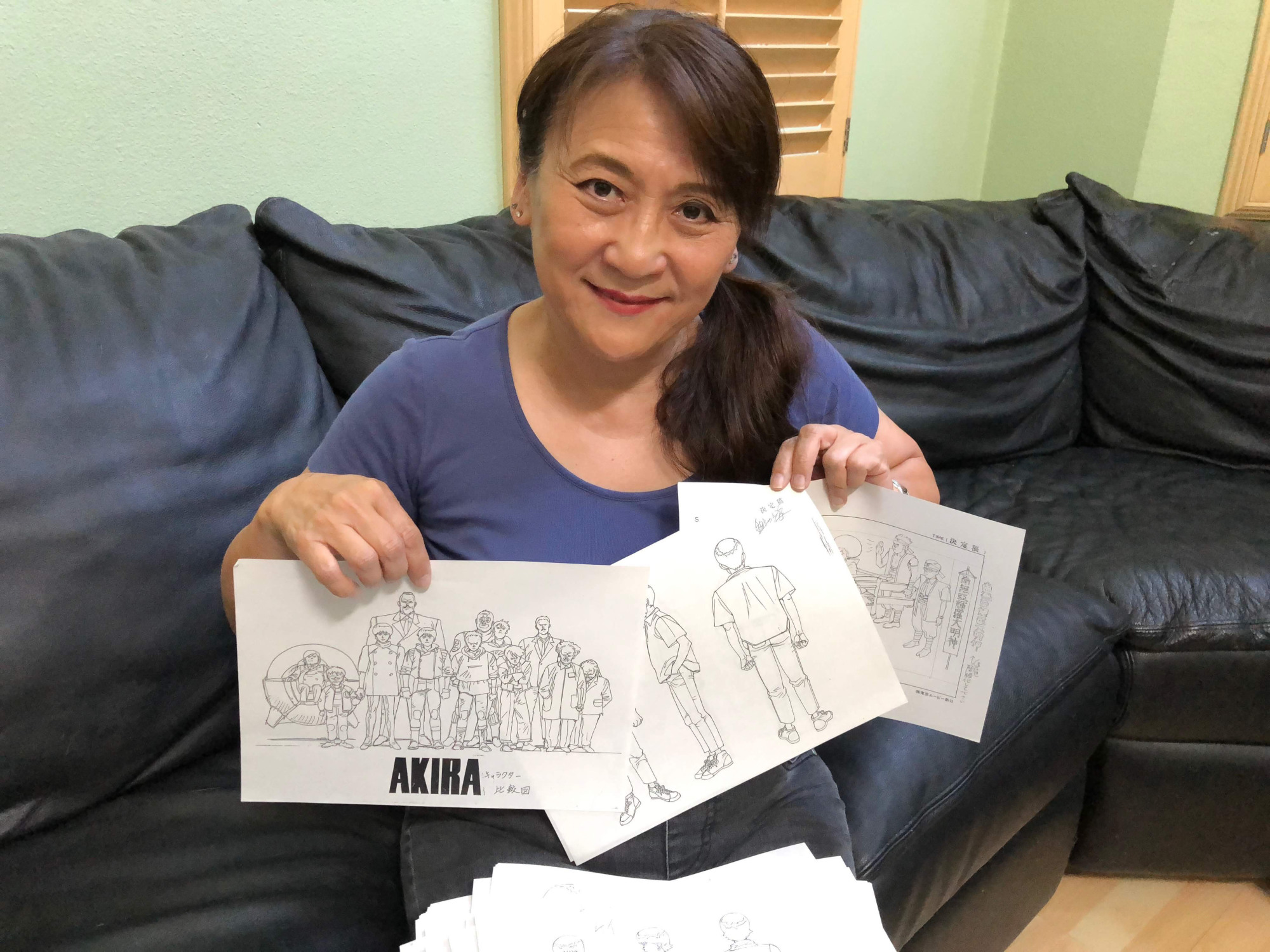

Kuni Tomita, a key animator on the film, says it was “incredibly hard” to meet Otomo’s exacting standards.

“We (animators) didn’t even use computers back then,” she says. “(It was) all hand-drawn. If you think about that, it’s incredible work. Lots of dedication.”

Joe Peacock, an “Akira” collector who owns a significant number of frames from the film, agrees.

“One hundred and sixty thousand frames of animation — all hand-painted,” Peacock says. “The more you learn, the more you realize this film really shouldn’t exist.”

“Akira” was released on July 16, 1988, and was generally well-received.

“The better you know Otomo’s work, the higher your expectations will be,” wrote Nozomi Omori in Kinema Junpo, the country’s film magazine of record. “And the film version of ‘Akira’ meets those expectations wonderfully.”

The Asahi Shimbun described the film’s setting, Neo-Tokyo, as “realistic” and “engrossing.”

In the year-end edition of Kinema Junpo, “Akira” came in at No. 4 on a poll of readers’ favorite films of 1988. It was up against some pretty tough competition in the animation department — Studio Ghibli’s “My Neighbor Totoro” and “Grave of the Fireflies” were also released the same year.

By the time its domestic theatrical run had come to an end, “Akira” had taken in ¥750 million at the box office — less than the film’s enormous budget, but more than enough for it to be considered a hit.

However, praise for the film was not universal. The Asahi Shimbun quoted audiences emerging from theaters who complained that the story was hard to follow. Despite having worked on the film herself, Tomita was able to relate.

“It looked great,” the animator says. “I couldn’t believe the high level of animation and everything. However, I had no idea what was going on in the story at the end.”

All in all, “Akira” had done well in Japan. In order to secure its reputation as a legend, however, “Akira” would have to go West.

The cityscape of Neo-Tokyo in the anime "AKIRA" © 1988 MASH•ROOM / AKIRA COMMITTEE All Rights Reserved.

Overseas influence

Today, the licensing of Japanese animation for overseas distribution is a multimillion-dollar industry. In the late 1980s, though, aside from a few heavily Westernized titles, anime was practically unheard of. This, however, was about to change.

In the United States, “Akira” officially premiered on Christmas Day in 1989. A mini-release took it to major cities across the country in early 1990 before receiving a wider release in arthouse cinemas the same year. Otomo traveled to the United States for the film’s New York premiere in October of that year.

The film was distributed by Streamline Pictures, an early U.S. anime licensor co-founded by Carl Macek, who had found success adapting a group of giant robot series from Japan into “Robotech” earlier in the ’80s. Streamline also later released the film on video.

In the United Kingdom, “Akira” was screened at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in January 1991. In attendance at the premiere was Laurence Guinness, from music label Island Records, who convinced the company to license the film for home video release — a decision that McCarthy says “kick-started the anime boom in the U.K.”

“(The film’s) impact was huge,” McCarthy says. “(There were) newspaper articles, worries about disaffected teens being scarred and warped by this trip on the ‘Orient excess,’ and shock and awe about how absolutely amazing it is as a piece of animation and a work of art.”

In addition to English, the film was eventually dubbed into German (twice), French (twice), Spanish (three times) and subtitled into many more languages. It received an updated Italian dub this year.

Some mainstream critics at the time dismissed the film.

Writing for the weekly newspaper Chicago Reader, Jonathan Rosenbaum called it “interminable” and “the equivalent of the dullest of all possible computer games.”

Others, however, seemed to be on board.

Writing for Variety, Edna Fainaru called it a “remarkable technical achievement” with “imaginative and detailed design.”

Richard Harrington of the Washington Post wrote that it was “intellectually provocative and emotionally engaging.”

Roger Ebert called it “very gory, very gruesome, but entertaining.”

Meanwhile, sci-fi fans whose pumps had been primed by films such as “Blade Runner,” the fiction of William Gibson and the small amount of anime they’d been able to get their hands on at the time now typically describe “Akira” as life-changing.

“I was dumbstruck by it,” McCarthy says. “Thirty years on it is still one of the most daring, imaginative, in-your-face political movies ever made.”

Carl Gustav Horn, manga editor at Dark Horse Comics, agrees.

“The movie just felt like a total package,” Horn says. “It was so exciting … it was going to set the world on fire.”

Despite (or perhaps because of) its dangerous, gritty atmosphere, the film’s dystopian vision of Neo-Tokyo was irresistible.

“American fans would start talking about their hometowns like ‘Neo-Dallas,’” Horn says. “Using that prefix meant you were looking at things from a sort of … ‘I wish my town were cool and cyberpunk like that.’”

McCarthy definitely saw parallels in such a perspective.

“The film’s imagined Tokyo was so achingly hip that people would have killed — or died — to live there,” she says.

“Akira” was “cool Japan” before the term had been officially adopted by government bureaucrats. Unlike the cute characters of “Pokemon” that were to eventually serve as Japan’s cultural ambassadors a decade later, the ultraviolent “Akira” had an edge — an edge that was strengthened by the historical context of the period.

“This was a time, in America at least, where Japan was thought of as an economic threat, kind of how we think of China now,” Horn says. “They talk about ‘soft power’ today, but back then there was this sense that maybe the power was going to be hard as well. You know their cars, you know their electronics, now here come their movies … in the days of ‘Akira,’ it had that weird vibe to it. You know, maybe Japan really is going to take over.”

It seemed a certain segment of the audience would welcome such a takeover. Over the next few years following the film’s release, a handful of distributors, following Streamline’s lead, set up shop to license and release anime in the West.

“Ghost in the Shell,” another hit anime film with cyberpunk themes that was released in 1995, was even co-produced with funds from U.K. distributor Manga Entertainment, which had originally been spun off by Island Records to release “Akira.”

Lasting legacy

In the intervening 30 years, “Akira” has never really disappeared. The film’s long-standing influence on Hollywood has been well-documented, with releases such as “The Matrix,” “Inception,” “Looper,” “Chronicle” and “Stranger Things” drawing inspiration from it in some fashion.

Most recently, the film’s famous motorcycle appeared in “Ready Player One.” In 2002, Warner Bros. secured the rights for a live-action “Akira” remake but the project is stuck in development limbo.

In Japan, those who worked under Otomo — Satoshi Kon, Takashi Nakamura and Hiroyuki Okiura, to name but a few — went on to become lauded anime directors in their own right.

“Akira” began to influence other aspects of pop culture as well. In the early ’90s, commercials for the home video release made their way onto cable networks such as MTV. Soon afterward, a clip of the film was used in the music video for Michael and Janet Jackson’s “Scream.”

Years later, Kanye West would replicate some of the scenes in his video for “Stronger,” later tweeting that “‘Akira’ and ‘There Will Be Blood’ are equally my two favorite movies of all time.”

Meanwhile, samples of the film’s thunderous polyrhythmic soundtrack and English dub made their way into tracks by artists such as Underworld, Sunbeam, Atari Teenage Riot, Pop Will Eat Itself, Sonic Subjunkies and more. By the mid-’90s, the sounds of “Akira” could be heard pumping through underground clubs and venues around the world.

“Akira” even influenced the way people dressed. Bootleg patches of the film’s iconic capsule logo — “good for health, bad for education” — have found their way onto hundreds of leather jackets over the years.

In 2017, streetwear brand Supreme released a series of shirts, sweaters and jackets featuring “Akira” imagery. The collection sold out in minutes.

For some, the cultural acceptance has been profound.

“Anime and comics used to be for geeks and dorks and losers,” Peacock says. “Now if you look around, I mean, we won.”

Having said all that, if “Akira” can be seen as the first anime of its kind, it can also, in many ways, be seen as the last.

“Akira” was released in 1988 at the height of Japan’s economic bubble, when spending more than ¥1 billion on an animated movie didn’t seem like a preposterous thing to do.

A scant few years later, Japan’s “lost decade” was underway. Although post-“Akira” anime films and series have grappled with the same cyberpunk themes, none have reached the same level of spectacle — or what cel collector Peacock calls the film’s “sheer oh-my-God aspect.”

“There was this problem, which almost became a cliche,” Horn says. “People were getting into anime, going, I’ve seen ‘Akira,’ what else is like ‘Akira’? And you responded, well, you know, not too much, really.”

Otomo seemed to have little interest in repeating himself, either. The director — who was inducted into France’s Order of Arts and Letters in 2005 — went on to write or helm several other anime films, but none were in the same cyberpunk style. His “Steamboy,” released in 2004, had production values that in some ways rivaled those of “Akira,” but its plot was widely panned by critics.

For all its spectacle (and despite its occasionally confusing narrative), “Akira” had ultimately connected with audiences on a level that went beyond mere flashy animation.

Otomo’s Neo-Tokyo was filled not just with high technology, but urban sprawl, disaffection and unrest.

Drawing from real-life events, Otomo evoked the postwar, post-nuclear mood of the 1950s, the student movements of the ’60s and the wave of “new religions” in the ’70s and ’80s.

“(Otomo raised) questions about inner city youth, social justice, corruption and public gullibility that are still unanswered,” McCarthy says.

The director was prescient not just about the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, but the danger of religious cults — Aum Shinrikyo carried out its sarin gas attack on Tokyo’s subway lines just a few years later — and the tottering instability of a society that, at least during the 1980s, seemed almost impervious.

The characters of “Akira” may have had superpowers, but they were no superheroes. They were orphans, punks, outcasts on the margins of society — characters to whom audiences around the world found they could relate.

“It’s society’s outsiders — those who don’t belong — who are more intriguing to draw,” Otomo said during an interview promoting his 2017 tie-up with streetwear brand Supreme.

If the past three decades are any indication, they’re also more intriguing to watch.

Read all #AkiraWeek articles

-

Akira: Looking back at the future‘Akira’: Looking back at the futureOn the 30th anniversary of the release of ‘Akira’ in Japan, we examine the enduring...

Akira: Looking back at the future‘Akira’: Looking back at the futureOn the 30th anniversary of the release of ‘Akira’ in Japan, we examine the enduring... -

Speak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkSpeak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkWant to give your nihongo a bit of biker edge? Let Neo-Tokyo be your...

Speak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkSpeak Japanese like an ‘Akira’ biker punkWant to give your nihongo a bit of biker edge? Let Neo-Tokyo be your... -

'Akira' inspires generations of foreign animators‘Akira’ inspires generations of foreign animators‘Why did you come to Japan?’ For many people, the answer is Katsuhiro Otomo‘s visionary...

'Akira' inspires generations of foreign animators‘Akira’ inspires generations of foreign animators‘Why did you come to Japan?’ For many people, the answer is Katsuhiro Otomo‘s visionary... -

'Akira' soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpiece‘Akira’ soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpieceGeinoh Yamashirogumi's epic soundscape still resonating with musicians and listeners decades later

'Akira' soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpiece‘Akira’ soundtrack featured music worthy of a visual masterpieceGeinoh Yamashirogumi's epic soundscape still resonating with musicians and listeners decades later -

Do you remember the first time you watched 'Akira'?Views from the street: TokyoDo you remember the first time you watched ‘Akira’?

Do you remember the first time you watched 'Akira'?Views from the street: TokyoDo you remember the first time you watched ‘Akira’? -

The enduring appeal of 'Akira,' the mangaThe enduring appeal of ‘Akira,’ the mangaThroughout multiple English-language incarnations of the cyberpunk classic, demand has never wavered

The enduring appeal of 'Akira,' the mangaThe enduring appeal of ‘Akira,’ the mangaThroughout multiple English-language incarnations of the cyberpunk classic, demand has never wavered -

The pain and the passion that fueled the creation of 'Akira'The pain and passion that fueled ‘Akira’For many of the animators who toiled to bring Neo-Tokyo to life, it was a...

The pain and the passion that fueled the creation of 'Akira'The pain and passion that fueled ‘Akira’For many of the animators who toiled to bring Neo-Tokyo to life, it was a... -

Collecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeCollecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeHow Joe Peacock became the owner of the world’s largest collection of ‘Akira’ cels.

Collecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeCollecting ‘Akira,’ one scene at a timeHow Joe Peacock became the owner of the world’s largest collection of ‘Akira’ cels. -

My deep dive into 'Akira' only scratched the surface of its legacyMy deep dive into ‘Akira’ only scratched the surface of its legacyA few months ago, I proposed to the editors at The Japan Times that we...

My deep dive into 'Akira' only scratched the surface of its legacyMy deep dive into ‘Akira’ only scratched the surface of its legacyA few months ago, I proposed to the editors at The Japan Times that we...