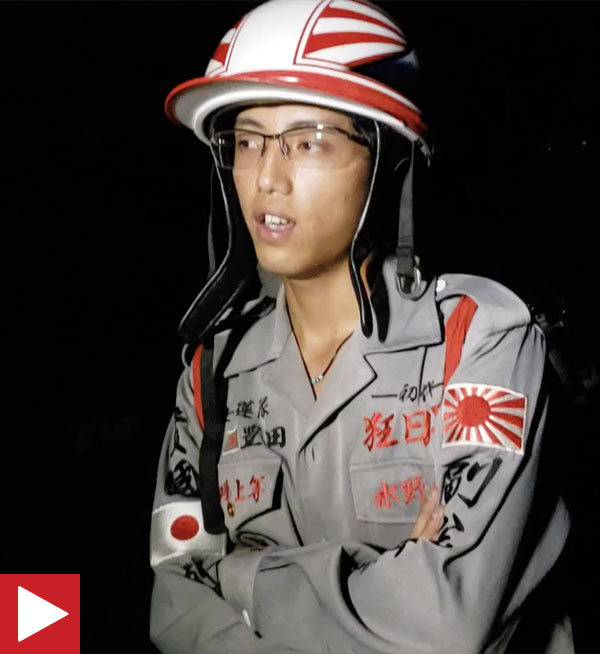

Twenty-year-old Yusei Mizuno, a former member of a motorcycle gang called Kyupii, relives memories of his adolescence in August as he sits on a bike in a deserted parking lot in the city of Toyota, Aichi Prefecture. TOMOHIRO OSAKI

Tracing its origins back to the heady days of motorcycle gangs in the 1970s, the style is making a comeback with youth in Japan

TOMOHIRO OSAKI

Staff writer

Standing in the darkness of a quiet parking lot in the city of Toyota, Aichi Prefecture, 20-year-old construction worker Yusei Mizuno starts to change into a tokkōfuku combat uniform he hasn’t worn for two years.

The change in Mizuno is immediate. Gone is the smiling former motorcycle gang member with an apparent crush on K-pop act Twice. He’s now glaring at the camera with his lips closed tightly, offering up a look that’s a mix of James Dean at his peak and classic Dirty Harry.

A provocative statement has been stitched onto the right breast pocket of the jacket that simply says, “Kenka jōtō,” or “Bring it on.”

“Wearing this gives you a rush of adrenaline. It makes you feel as if you’ve become tougher … stronger,” Mizuno says when asked about the uniform, the same outfit he used to wear when he went on rides with his friends.

Sewn onto the back of Mizuno’s uniform are three large kanji: “insanity,” “Japan” and “awe.” These characters represent the name of his now-disbanded bōsōzoku (motorcycle gang) Kyupii.

Kyupii’s former leader, 20-year-old Taichi Sudo, says the gang’s uniform was ultimately a means of group self-expression.

“It was our way of saying, ‘This is who we are,’” Sudo says. “No matter what people think of us, this is our style. Wearing the same uniform made us one. It bonded us as a team.”

Mizuno and his former gang’s fascination with tokkōfuku makes Kyupii, which disbanded in 2016, one of a dwindling few devotees of a sartorial culture that has slid into obsolescence amid a decline of motorbike gangs.

Industry insiders say tokkōfuku culture had all but disappeared in the wake of ongoing police crackdowns and statements by authorities who demonized the attire as tantamount to encouraging juvenile delinquency.

Now, however, the uniform has carved out an increasingly diverse, devoted and well-behaved pop culture clientele that has helped it inch toward outgrowing its taboo image.

Working-class origins

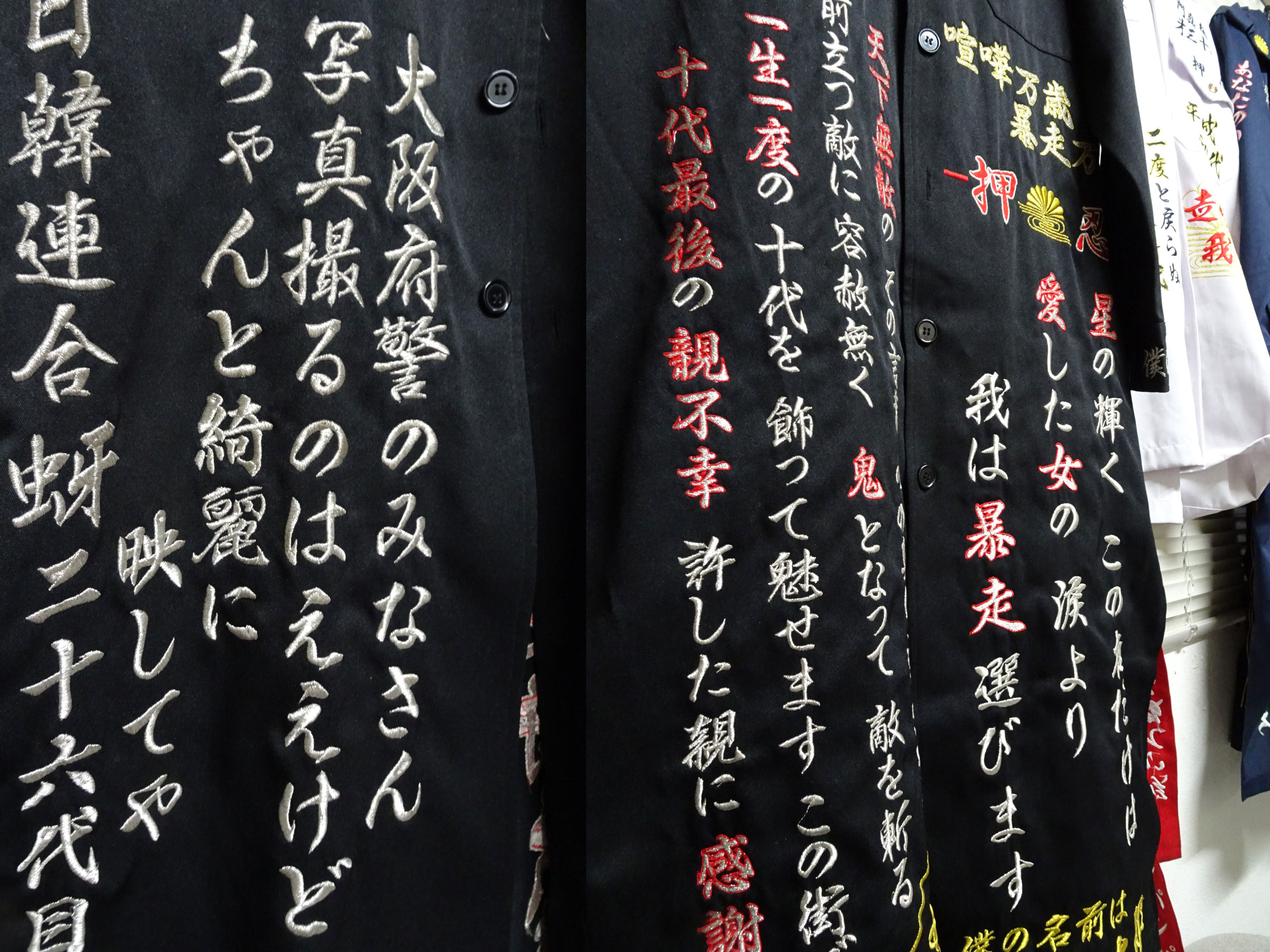

Tokkōfuku uniforms are often paired with items such as hachimaki headbands, tasuki sashes and even surgical masks. It has also been common for people who wear the uniforms to stitch nationalist symbols and phrases near the shoulder or breast pocket, including the Rising Sun flag and Imperial Chrysanthemum crest.

Although tokkōfuku includes the Japanese word “tokkō,” which means “special attack,” experts say this has nothing to do with kamikaze pilots who flew bomb-laden planes into enemy vessels during World War II.

According to Kenichiro Iwahashi, a self-styled expert on juvenile delinquency who is often described as the “kingpin of Japan’s yankii (punk) world,” tokkōfuku dates back to the 1970s when motorcycle gangs based in Tokyo’s working-class neighborhoods began wearing uniforms similar to the military jackets favored by the nation’s right-wingers.

The gangs were inspired to take a similar outlook, which significantly changed their appearance. Prior to that, Iwahashi says bōsōzoku members dressed more casually in blue-collar jackets and Hawaiian shirts. The 51-year-old speaks from experience: He was a Yokohama-based bōsōzoku member in the 1980s.

“Back then, the design of many tokkōfuku uniforms — especially those in the Kanto region — was strongly affected by right-wing culture,” Iwahashi says. “As a result, popular stitches included phrases such as ‘Shichishō hōkoku’ (‘Live your life seven times in dedication to your country’).”

The designs of the uniforms in the ’80s were also relatively simple, often featuring little more than the name of a gang and the rider’s personal motto, Iwahashi says.

However, amid an intensifying police crackdown on reckless driving in the 1990s, more and more youth abandoned their bikes but not their tokkōfuku, which were still key to their group identity.

Wearing these uniforms, they would attend local festivals and create a scene by brandishing flags or chanting slogans. It was around this time that the phrase “toho bōsōzoku” (“walking motorcycle gang”) was coined.

“Some of these kids still rode bikes, yes, but others simply didn’t. They focused on screwing around at festivals instead,” Iwahashi recalls. “In my days, a motorcycle gave us status. … Over the years, however, the uniforms have become all that matters.

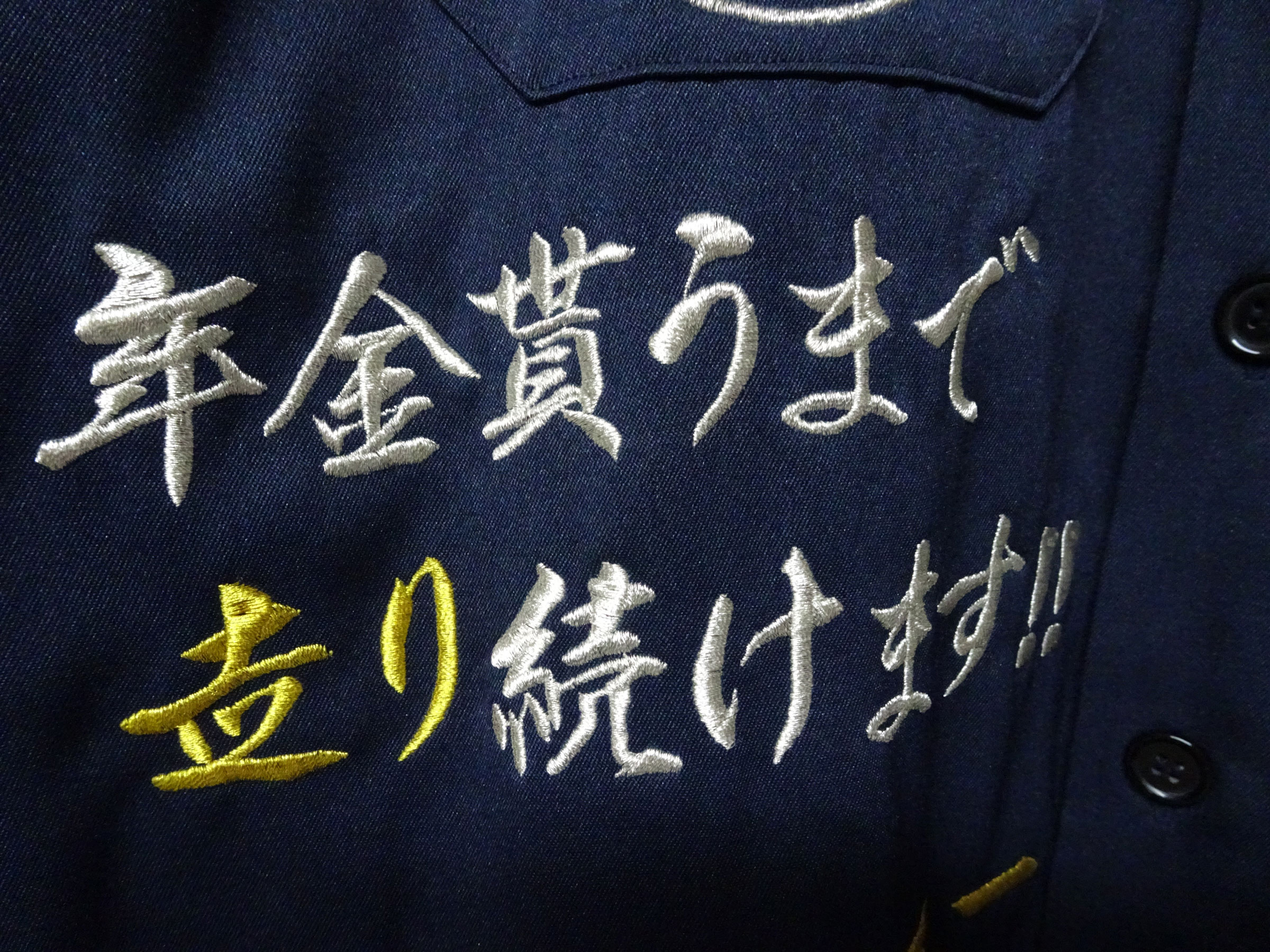

“Designs today are often extremely intricate and bold — so much so that you see little empty space left. … Kids go to great lengths to invest in the embroidery work — I myself have seen uniforms that would be worth more than ¥1 million,” Iwahashi says.

By the late 1990s, the authorities had all but declared war on the uniforms, generally regarding them as a ticket to delinquency. In 1997, a garment maker who embroidered the uniform in Osaka was arrested on the grounds of “aiding and abetting” misbehaving motorcycle gangs, a move that set a precedent for arrests that followed.

In another first, the Osaka Family Court authorized a request by the police to confiscate tokkōfuku worn by local bikers in 2002. The request was granted because, at least according to police records, the court agreed that the uniforms “inspired fear and encouraged reckless driving.”

A collection of tokkōfuku uniforms embroidered by garment maker Kazuhiro Nakagawachi hangs on a wall in his prefabricated office in Kyoto in August. TOMOHIRO OSAKI

Social stigma

Today, tokkōfuku uniforms are almost on the brink of extinction. Not only have the authorities clamped down on the uniforms, the number of bōsōzoku nationwide has also fallen sharply in recent years.

The latest National Police Agency statistics show the number of motorcycle gang members totaled just 6,220 in 2017. As many as 42,510 young people had been a gang member at the number’s peak in 1982.

“Orders for tokkōfuku used to arrive en masse in the runup to festivities such as Tanabata (July 7) or New Year’s Day, as kids often drove recklessly during these events,” says Toshio Aoki, owner of Kanagawa-based apparel shop Fashion House Aoki, which specializes in selling punk-style clothes. “Police officers would occasionally visit our store and politely ask us to decline embroidering signature phrases such as ‘Kenkei datō’ (‘Police be damned!’). That’s no longer the case.”

Kyoto-based garment maker Kazuhiro Nakagawachi, who has spent nearly 20 years of his career catering exclusively to the members of motorcycle gangs and other disenfranchised youth, agrees.

“There are a few kids who still go about showing off their tokkōfuku at local festivals, but the days when kids would ride around on motorcycles in that getup are practically gone,” he says.

Nakagawachi, a former hotel employee, decided to work in this industry in 1999, enthralled by what he describes as the “coolness” of tokkōfuku.

Although he enjoys his job, Nakagawachi also admits to having mixed feelings about it.

He says there’s a tacit understanding among those in the sewing industry that embroidering tokkōfuku is “taboo.”

“There are people out there who think what I do makes me something of an accomplice to juvenile crimes,” he says, “so a part of me feels kind of guilty for what I do.”

Nevertheless, the unassuming 47-year-old rejects the notion that tokkōfuku is an unconditional evil.

Despite the uniform’s menacing look, Nakagawachi says the clothes often include an array of amusing jokes and heartwarming poems. Teenagers will, for example, thank their parents for putting up with their follies or rhapsodize about their romantic partners.

“Quite a few kids actually ask me to stitch messages of friendship and gratitude toward parents and teachers on their tokkōfuku,” Nakagawachi says, adding that they’ve increasingly been used as a special costume for 15-year-olds to wear at their graduation ceremonies.

“There are also boys who write poetry on how they feel about their girlfriends. Reading and embroidering their poems makes me blush sometimes,” he says, laughing. “In a sense, the uniforms are proof that you’ve lived your youth to its fullest. ... It’s my job to create a special memory for them.”

This view is echoed by 38-year-old company employee Ryusuke, a former member of Hiroshima-based biker gang Kannon Rengo. He spoke on condition of being identified only by his first name for privacy issues.

“My friends and I would spend days together, racking our brains and trying to come up with poems that we wanted written on our tokkōfuku,” he recalls. “I mean, we were boys who didn’t give a damn about studying in school but, here we were, suddenly opening up our notebooks and using what little poetic talent we had.”

In his youth, Ryusuke spent five years contesting the constitutionality of an anti-bōsōzoku ordinance that was enacted by the city of Hiroshima in 2002. It outlawed the gathering of a “fear-inducing” assembly that would, among other things, be wearing “eccentric clothing” — a euphemism for tokkōfuku — in public.

Aside from the law’s potential infringement on a citizen’s rights to freedom of assembly and expression, some pundits at the time said it amounted to labeling anyone who wore tokkōfuku as a criminal, thereby “stigmatizing” owners and denying them the right to wear what they wanted.

Ryusuke was arrested for violating the ordinance in November 2002, when he organized a gathering at a public square with friends who were dressed in combat uniforms. It was, he recalls, a desperate act of protest against an ordinance he thought trampled all over his rights, and Ryusuke subsequently fought his case all the way up to the Supreme Court, which ruled against him in 2007 and declared the ordinance constitutional.

“What bōsōzoku does — rev up motorcycle engines in the middle of night and disrupt other people’s sleep — is a pure nuisance so, looking back, I do believe they deserved to be cracked down on,” Ryusuke says. “But does their misconduct also make them undeserving of the right to wear and express what they want?”

Artistic expression

Although the uniforms have mostly outlived their purpose as a way of self-expression for disaffected teens, they are now finding new fans among the more well-behaved youth of Japan.

Kazutaka Kurio, a spokesman for Okayama-based Pros Online Shop, one of the longest-running retailers in the country selling punk-style apparel, says around 90 percent of the orders it receives for the uniforms today have nothing to do with biker gangs, but reflect a demand from “ordinary people.”

“For example, families and company employees purchase tokkōfuku as gifts for their elders on occasions such as their 60th birthdays. These designs will typically feature gold letters stitched onto the back that read ‘Shuku kanreki’ (‘Happy 60th anniversary’),” Kurio says, adding that newlyweds sometimes wear jackets adorned with the phrase “Kekkon jōtō” (“We aren’t afraid of marriage”).

Also driving this niche business today are hard-core fans of certain bands, idol pop acts and anime characters who take part in concerts and other events. Those designs are full of devotional messages for their idols.

One such modern fan is Hiroki Kurihara, 26. Decked out in a blue, long-hemmed tokkōfuku with pants tucked into his tabi socks on a sweltering summer’s day, he had traveled from Hyogo Prefecture to the Yokohama Arena for an AKB48-related event. On the back of his jacket was the name of his favorite idol: HKT48 member Hana Matsuoka.

Kurihara says the outfit cost him about ¥60,000 and it has become his go-to costume for concerts and so-called handshake events where fans can chat with their idols in person.

“I began wearing it about a year ago after Matsuoka told me that she was sad she didn’t have any hard-core fan she could recognize as being hers,” Kurihara recalls. “I was like, ‘Sure why not wear tokkōfuku then?’ Tokkōfuku visualizes my support for her. … I’m determined to keep wearing it until she graduates (from the current group).”

The great lengths Kurihara goes to in proclaiming his love for Matsuoka not only resonate with like-minded fans of idols but also with aficionados of anime characters.

Part-time worker Kazuki, 20, is a dedicated “Love Liver” — as fans of the anime series “Love Live!” are called. On a recent Saturday, he was attending a gathering of fellow Love Livers at Tokyo Big Sight, wearing a red tokkōfuku with the name of his favorite character: Dia Kurosawa. He spoke on condition of using only his first name.

Kazuki says the uniform has resulted in him frequently getting asked for selfies and helped him network with other fans, which in turn fosters a sense of camaraderie with the community.

But he also acknowledges that the uniforms haven’t entirely overcome their negative image.

“To be honest, I think there are people out there — and maybe even in the community — who may get offended at the sight of someone wearing tokkōfuku, which is still largely associated with bōsōzoku or punks,” Kazuki says. “The uniforms always put us at the center of the attention, which means that any rude behavior in public on our part risks soiling the name of ‘Love Live’ as a whole. We are super-careful not to let that happen.”

Another Love Liver at the Tokyo Big Sight, a 37-year-old company employee from Yokohama, describes the uniform as a one-of-a-kind piece of art that he himself has brought into existence.

His intricate, meticulously well-thought-out uniform is covered in exactly 445 characters — a three-digit figure that phonetically represents the first name of the love of his heart, Yoshiko Tsushima, another character from the show.

“There are, of course, official T-shirts you can buy and wear to show up for events like this, but it just makes you look the same as everyone else,” he says, declining to be identified in case his employers found out. “However, the design of this embroidery work is something I invented from scratch. Nothing else comes close to it and I’m proud of that.”

At a recent “Love Live!” event at Tokyo Big Sight, a 37-year-old company employee from Yokohama (right) shows off a meticulously designed tokkōfuku that he says contains exactly 445 characters — a three-digit figure that phonetically represents the first name of his love, Yoshiko Tsushima, a character from a popular anime series. TOMOHIRO OSAKI

Common tokkōfuku slogans used today

Kenka jōtō

Bring it on

Gokuaku hidō

Inhuman

Tenka muteki

Utterly invincible

Yuiga dokuson

Only I am holy

Kenkei datō

Police be damned

Nenshō jōtō

Screw youth prison

Zenkoku seiha

Conquer the nation

Yūkoku resshi

Patriotic martyr

Tokkō damashii

Soul of special attack

Sōshi sōai

Dying to ride motorbikes