HISTORY

The Todai Riots: 1968-69

Students assemble on the University of Tokyo grounds during its occupation in the late 1960s. HITOMI WATANABE

A photographer who documented the occupation of the University of Tokyo from inside the barricades half a century ago remembers the final days of resistance

ALEX MARTIN

Staff writer

Riot police at the University of Tokyo haul off a man wearing a white helmet, cuffed hands clasped above his bowed head. His expression is a mixture of resignation and defiance, but the fine details are hard to discern, obscured by the dark shades of the monochrome photograph he is depicted in — where he remains frozen in time. In the foreground, an officer is speaking into his transceiver, perhaps reporting back to the tactical unit in charge of operations or answering a query from other troops conducting a sweep of the campus.

Another image shows a protester propelling a Molotov cocktail from a balcony toward an approaching blast from a water cannon.

There are also moments of candor: An activist with his mouth full of an onigiri rice ball; students playing a game of go next to a bottle of Suntory whisky; and a man, fast asleep on the floor, with a butt-filled ashtray sitting by his elbow.

These are considered to be the only photographs from behind the barricades documenting the final months of riots that engulfed the nation’s top educational institution. The uprising culminated in a historic two-day showdown 50 years ago on Jan. 18 and 19, 1969, that saw the last occupants of the Yasuda Auditorium captured by police, marking the end to a decade of violent, and occasionally deadly, student protests.

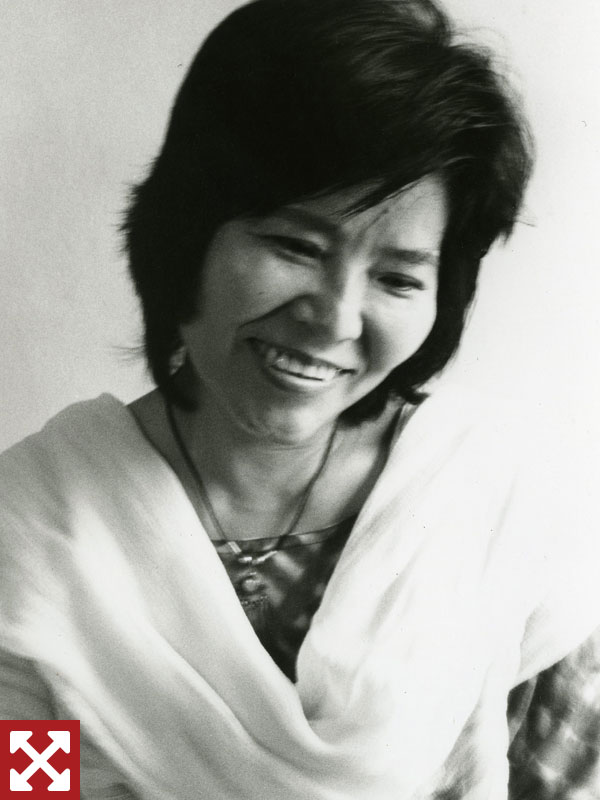

“I didn’t really have any strong political views at the time,” says Hitomi Watanabe, a photographer who was granted sole access to shoot inside the auditorium at the time.

A graduate of the Tokyo College of Photography, she had been wandering the streets of Shinjuku, then home to the nation’s counterculture, snapping photographs of buildings, alleys and the workers who fueled the nation’s postwar economic boom.

Watanabe was also drinking buddies with artist Michiyo Yamamoto, often crashing at her flat near Shinjuku.

“Sometimes at night, Yamamoto’s partner, Yoshitaka, would return home. He’d simply acknowledge us and then just smoke cigarettes — he wasn’t a very talkative guy,” Watanabe recalls.

Then a postgraduate student at the University of Tokyo, Yoshitaka Yamamoto would soon be elected the leader of his university’s branch of Zenkyoto, the All Campus Joint Struggle League, and emerge as one of the central figures alongside Akehiro Akita, chairman of Zenkyoto’s Nihon University branch, in the student movement that swept across the nation.

“Yamamoto’s quiet but determined demeanor inspired me,” Watanabe, 73, says on a recent afternoon at a cafe in the Tokyo neighborhood of Oji.

“I began shooting his portraits,” she says, a project that would impact her life and career in unforeseen ways.

Global undercurrent

This was 1968, a significant year for Japan’s student movement that coincided with the impending renewal of the U.S.-Japan Mutual Cooperation and Security Treaty, whose amendment in 1960 triggered the first wave of the decade’s social protests, leading to the death of a female undergraduate student of the University of Tokyo during police clashes, and eventually the resignation of Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, grandfather of current Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

It was also a time that saw uprisings raging around the world, including the civil-rights movement and anti-Vietnam War protests in the United States, the Cultural Revolution in China, massive demonstrations by students and workers in France and Germany, and Czechoslovakia’s failed Prague Spring.

Protests in Japan in 1968 were far more coordinated and larger in scale compared to a decade earlier, beginning with a demonstration against the arrival of the nuclear-powered USS Enterprise, which was due to visit a U.S. naval base in Sasebo, Nagasaki Prefecture, in mid-January before heading to Vietnam.

Leftist student organization Zengakuren, an entity formed by groups with varying degrees of radicalism, as well as other peace organizations and political parties assembled to the small town to protest the port call. Fueling the move was the so-called Haneda incidents of the year before — ferocious student demonstrations against Prime Minister Eisaku Sato’s visit to Japan’s Asian neighbors and the United States that stirred the anger of those viewing the move as the government’s collusion with Washington and its policy in Vietnam.

Conservatives viewed the Enterprise’s visit as crucial to Japan’s defense in a volatile region, while others saw the move as the government’s blind support of U.S. strategy in East Asia. Beginning on Jan. 17, these sentiments exploded at Sasebo, as student protesters clashed with police armed with batons and tear gas outside the U.S. naval base. The struggle soon became lopsided, with men in uniform viciously battering defenseless students and raising widespread criticism of police brutality.

Meanwhile, at Nihon University, the nation’s largest institution of higher learning, a scandal over the embezzlement of ¥2 billion of university money sparked mass demonstrations and led to the formation of the all-inclusive Nihon University Zenkyoto that blockaded the campus and pushed for administrative reforms. The Zenkyoto movement for on-campus conflict spread rapidly to other campuses across Japan, paralyzing universities with student strikes at an unprecedented scale.

At the University of Tokyo, also known as Todai, protests by medical students over the working conditions of interns gradually intensified and led to the occupation of the brick-clad neo-gothic Yasuda Auditorium, considered a symbol of the institution’s Hongo campus in Bunkyo Ward. What had originated as disputes over money and university reform evolved into one embracing broader political issues, with Zenkyoto and other “new left” students embracing anti-establishment slogans that appeared on flyers and campus graffiti.

Problematic participation

Watanabe, then in her 20s, had been following Yamamoto since around autumn that year, filming the daily protests and meetings taking place inside the University of Tokyo. However, being a young, female photographer with no visible affiliation to the various sects involved in the dispute proved problematic.

“I was viewed with suspicion. Some thought I was a spy, others thought I was a newspaper reporter,” Watanabe says. “Then one day, I was given an armband that read ‘Zenkyoto,’ essentially making me a part of them, and that gave me access inside.”

Many of Watanabe’s photographs from those months are compiled in a collection titled “Todai Zenkyoto 1968-1969.” The images depict Yamamoto as a slim, handsome man with a beard. The lens would capture him orating at rallies, or wearing a helmet and speaking to fellow protesters.

However, an arrest warrant would soon be issued for Yamamoto, forcing him to go underground. Watanabe wasn’t deterred — at that point she was already transfixed by the heat of the movement and flitted between the University of Tokyo’s Hongo and Komaba campuses, documenting scenes that would become the definitive images chronicling the historic struggle in Japan’s most elite university.

The fervor reached its boiling point in January 1969 in what would later be called the “fall of Yasuda Auditorium.”

“Radical students holed up in Tokyo University’s Yasuda Auditorium Saturday withstood a 10-hour siege by riot police who seized control of 16 other buildings held by the students on the university’s Hongo campus,” The Japan Times reported in its Jan. 19 issue about the previous day’s clash that involved 8,500 riot police sealing the campus. “The students hurled blazing Molotov cocktails, acid bottles and huge chunks of concrete slabs and rocks at the policemen from the roof of the auditorium.”

In its Jan. 20 issue, the paper said the auditorium “lay devastated Sunday evening after riot police completed their sweep, arresting more than 370 students who had holed up there.”

It described the day as the “end of more than six months of occupation of the auditorium by the students who seized it on July 2,” adding, “radicals spearheaded by medical students first occupied it on June 15 but were evicted by riot police two days later,” an event that “ignited the anti-establishment feeling of all Todai students.”

Yamamoto, who pursued a career in academia following his days as a student activist, typically declines all interview requests regarding his time as the University of Tokyo’s head of Zenkyoto. He did, however, contribute an essay for Watanabe’s photobook, looking back at the tumultuous period and describing her stills as depicting both the “sense of liberation and, strangely, calmness” inside the barricades.

Student activity soon began to wane as the government drafted new legislation that granted police more authority to crack down on campus disturbances and, by the end of 1969, much of the barricades at universities had been taken down. By 1970, student activism had been almost entirely suppressed by police, while the economy continued to grow at a fast pace — as the nation became wealthy, people were no longer sympathetic to radical student movements.

In June, the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty was renewed and, apart from some extremists who formed the Japanese Red Army that went on to launch terrorist attacks both at home and abroad in the name of world revolution, most students returned to a state of political apathy.

Watanabe’s zeal also began to fade as the movement subsided.

“How should I describe my feeling … it was as if there was nothing left, and I didn’t want to remain in that depressing state,” she says. “There were others who went through much harder times. Some became sick, some committed suicide.”

It was an end of an era, and the sense of emptiness that nagged at Watanabe prompted her to leave the country.

“I decided to embark on a journey,” she says. This was 1972, and for the next quarter of a century she would travel for extended periods in Southeast Asia and South Asia, particularly India and Nepal. Her work no longer reflected the impassioned ideals of youth but assumed a tone of spiritualism and deep meditation.

Student activism

Kyoko Tominaga, an associate professor of sociology at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto and an expert on social activism, says the student movement of the period dispersed and evolved into local grass-roots movements often led by activists who were vocal in the 1960s.

Environmentalism became a focus, as national awareness heightened following protests over Minamata Disease, a 1950s industrial disaster that left tens of thousands of people poisoned after toxic wastewater containing methyl mercury from a Chisso Corp. chemical plant leaked into Minamata Bay in Kumamoto Prefecture.

“Anti-pollution campaigns, Minamata Disease and opposing construction of shinkansen lines and dams, as well as regional feminist movements, discrimination against those with disabilities and resident Koreans — these were some of the issues being tackled,” she says.

Such movements gradually took the form of nonprofit organizations, she says, spawning numerous groups dedicated to these and other causes.

After Japan’s asset-price bubble popped in the early 1990s and the nation entered the so-called lost 10 or 20 years of economic malaise, issues such as poverty and the plight of temporary workers gained traction. Demonstrations against the Iraq War gathered steam in the 2000s, while this decade saw several major social uprisings, including the 2012 anti-nuclear demonstrations held weekly outside the prime minister’s residence in reaction to the restart of two nuclear reactors following the 2011 earthquake, tsunami and triple meltdown at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, and the emergence of the Students Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy (SEALDs) protest group.

Instead of helmets and Molotov cocktails, these youths donned designer jeans and played hip-hop in their campaign against security legislation bulldozed through the Diet by Abe’s ruling coalition that reinterprets Article 9 of the Constitution to allow Japan to exercise the right to collective self-defense. The group, comprised of loosely knit members across the nation connected via social media, was credited with mainstreaming political activism, the likes of which have rarely surfaced in a nation where voter turnout among the young is doggedly low.

The movement was short-lived, however, with SEALDs announcing its disbandment 15 months after its formation, evolving into a successor organization and other splinter groups.

Tominaga, 32, hosts weekly classes at Keio University’s Hiyoshi campus, where she lectures on social activism.

“The impact of social media is immense, providing logistics and a means to rally crowds with relative ease,” she says, one reason why organizations such as SEALDs were able to morph into a considerable movement. “However, there’s a negative aspect in how this may have made such movements transient.”

And compared to the student activists of the 1960s, youths today are prone to consider themselves socially vulnerable and may lack the competitive urge of previous generations, she says.

“They face pressure against openly conveying political views in classrooms and seminars, especially if it’s anti-establishment,” she says. “Some even seek solace in the anonymity of demonstrations, in how people standing next to them won’t know who they are.”

A first-year Keio University student at Tominaga’s lecture who asked to remain anonymous says he occasionally attends Diet demonstrations but hides his face so he won’t be identified. “I’m scared of how it could impact my chances in finding a job,” he says. “I know my parents will be concerned, so I’ve never told them about it and don’t plan to.”

Others such as Shunsuke Tanaka, a second-year Keio student, are open about their political leanings. On his part, Tanaka expresses an interest in a variety of issues, including the contentious plan to relocate operations at U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma from a crowded residential area in Ginowan to the coastal district of Henoko, known for its beautiful coral reefs.

But the 21-year-old, who says he attends seminars and hosts events to discuss these and other topics, admits he thinks he’s an anomaly among fellow students. “I don’t really talk about these things with my classmates,” Tanaka says.

Atsushi Nozawa, a researcher at the University of Tokyo who has been working with victims of Minamata Disease, echoes Tominaga’s observation. “I harbor a sense of crisis toward students who learn what they are taught but are reluctant to take a step further,” Nozawa says.

Students stand on the roof of a building at the University of Tokyo during its occupation in 1969. HITOMI WATANABE

Historical relevance

Sifting through her pile of black-and-white stills, Watanabe fondly explains who some of the people caught on camera are, recollecting the wild days that kick-started her career as a professional photographer.

“My, how we have grown old. We used to be heavy drinkers but we can’t tolerate much now,” she says.

Watanabe is old-school and prefers phone calls and letters to email as her primary means of correspondence.

“I’ve lost the addresses of some of the folks from that time,” she says. However, she occasionally sees Yamamoto and his wife when they visit her photo exhibitions.

The 50th anniversary of the 1968-69 student uprisings has renewed interest in her photographs, leading to a paperback reissue of her photo collection by publisher Kadokawa Corp. last year.

Watanabe welcomes the attention — for the longest time she had donated her images of the University of Tokyo and the student activists upon request.

“It was only after it made it into book form that I made some money,” she says.

And the rare photographs’ historical relevance only increases over time.

“The images are irreplaceable,” she says, “since I was the only one there to take them.”