CULTURE

Eternal saints

The art of self-preservationShinnyokai COURTESY OF RYUSUIJI DAINICHIBO

Examining the extreme ritual behind the monks who spent years turning themselves into mummies while

they were alive

ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Tsuruoka, Yamagata Pref.

Staff writer

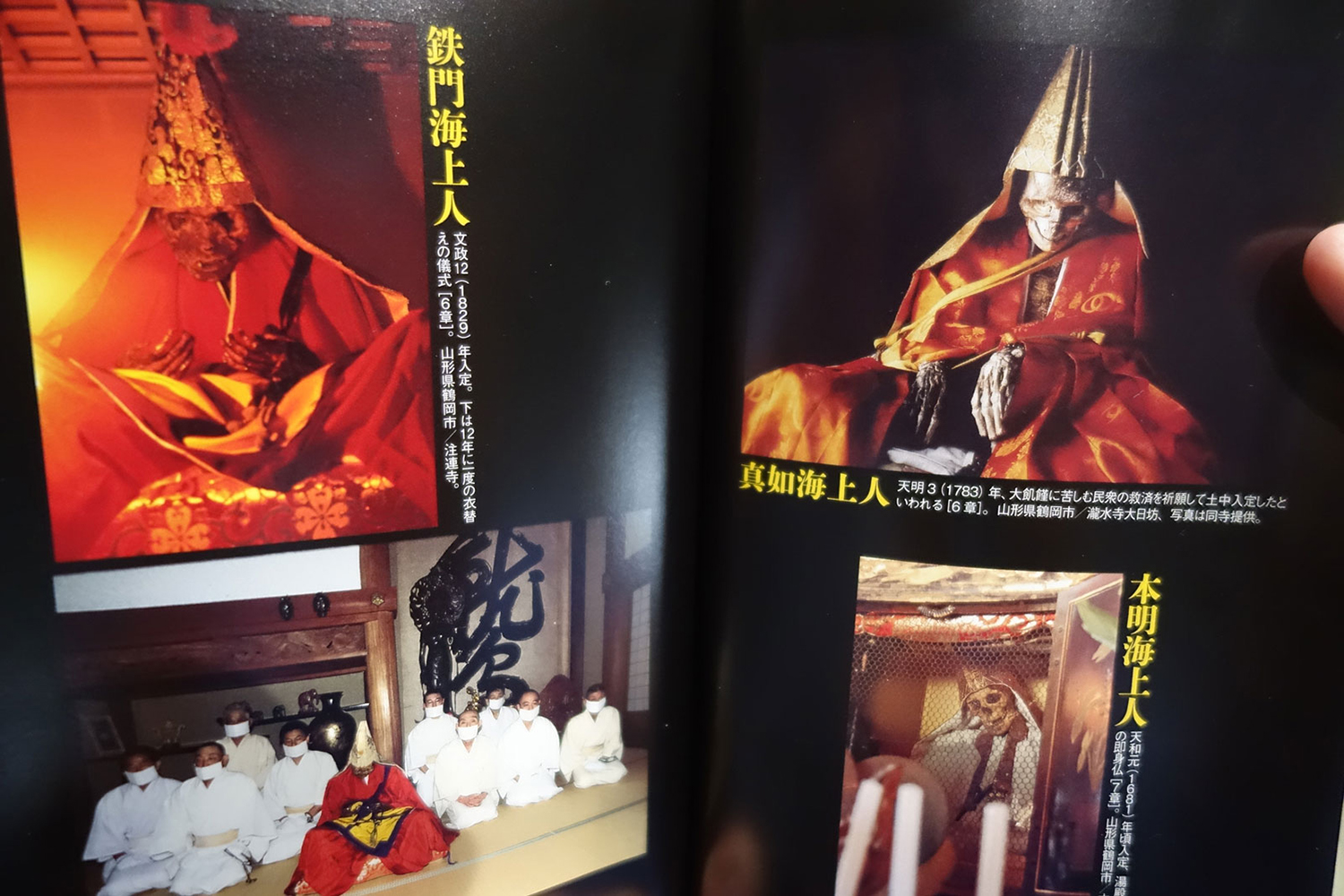

Perched cross-legged on an altar in one corner of Churenji Temple, cupped palms facing upward, the monk Tetsumonkai is set up for perpetual meditation – just as he intended as he lay dying nearly two centuries ago.

The skeletal figure draped in clerical robes is one of eight self-mummified monks – sokushinbutsu – found in the northeastern prefecture of Yamagata, among 18 thought to exist in Japan as a whole.

Several of these emaciated remains of zealots who endured extreme fasting to attain Buddha-hood are enshrined in old Shingon Buddhist temples sitting in the shadows of sacred Mount Yudono.

They represent a unique tradition associated with the area’s practitioners of Shugendo, an old ascetic religion combining aspects of mountain worship with Shintoism and esoteric Buddhism, in which practitioners (shugenja, which are sometimes called yamabushi), submitted to harsh training in the hope of achieving enlightenment and supernatural powers.

I first heard of these parched saints decades ago as a child visiting Tsuruoka, my mother’s hometown, during summer holidays. To a kid who thought mummies were bandaged, undead monsters in horror flicks, or dried-up Egyptian pharaohs exhibited in museums, it seemed peculiar that adults talked about them as if they were respected, kind uncles — local elders overseeing the well-being of their communities.

I had forgotten about these venerated mummies until August, when I read that a previously out-of-print 1996 book by Masashi Hijikata, “Nihon no Miira Botoke o Tazunete” (“In Search of Japan’s Mummified Buddhas”), had been republished. I bought a copy and discovered that Tsuruoka was a mecca for monks who would mummify themselves.

I already had plans to visit Tsuruoka in September to attend the third-year memorial service for my late grandmother. My trip gave me an opportunity to explore those curious sages from centuries past, whose bodies were immortalized as testament to the religious zeal that drove some to physical extremes that are perhaps beyond comprehension in today’s increasingly secular society.

According to Hijikata,“while methods vary, the practice of mummifying respected priests as a form of worship is relatively common in East Asia and can be found in the Korean Peninsula, China, Taiwan, Vietnam and Nepal, not to mention Tibet, where monks were embalmed and preserved after their passing.”

Hijikata heads the Sendai-based publisher Araemishi. He spent four years traveling across Japan researching his book, offering an intriguing look into the history and folklore surrounding the self-mummified Buddhas through anecdotes he collected from priests, followers and other locals. I spoke to him in Tokyo ahead of my trip to Yamagata.

He explained how the custom likely traced back to the first millennium, with early examples found in “Song Gaoseng Zhuan,” biographies of eminent monks compiled during China’s Song Dynasty (960-1279).

HIjikata said one story describes a monk who settled on Mount Jiuhua (in what’s now Anhui province), one of the four sacred mountains in Chinese Buddhism. The monk subsisted on minimal food while dwelling inside a stone chamber, which became his tomb when he died at the age of 99. Three years later, his disciples opened the chamber to find their master mummified in lotus position. They hoisted out and enshrined his body.

In Japan, the unusual phenomenon centered on Mount Yudono, which is grouped together with two other mountains, Mount Haguro and Mount Gassan, to form the Dewa Sanzan mountains.

While Mount Haguro came to be affiliated with the Tendai sect of Buddhism, temples that worshipped Mount Yudono belonged to the Shingon school of Buddhism founded by Kukai (774-835), a Heian Period (794-1185) monk and monumental figure in Japanese Buddhism, whom local legend credits with establishing Mount Yudono as a site for ascetic practice.

Hijikata said that during the Edo Period (1603-1868), Dewa, the area that now comprises Yamagata and Akita prefectures, was a spiritual center that rivaled Shikoku’s 88-temple pilgrimage and Mount Koya, the giant temple settlement in Wakayama Prefecture founded by Kukai.

“That also meant a lot of money poured into Dewa, leading to a rivalry between the Shingon and Tendai sects over control of the sacred mountains,” Hijikata said. “The competition over orthodoxy intensified to the point where Mount Yudono’s Shingon followers began adopting radical interpretations of Kukai’s teachings.”

To get a better understanding, I contacted Eric Swanson, an old college friend who studied esoteric Buddhism at Koyasan University for his master’s degree and who is now a doctoral candidate in the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations at Harvard.

“Although one could argue that the doctrinal basis of sokushinbutsu is based on Kukai’s sokushinjobutsu, there are major differences between the two,” Swanson said, explaining that in this case the character “jo,” meaning “to become,” is significant.

By relying on the ritual practices of the Buddhist tradition that Kukai transmitted to Japan from China, Kukai asserted that a Buddhist practitioner could attain full enlightenment in a single lifetime.

“What is important here is the claim that the potential for this enlightenment is achieved ‘within one’s lifetime,’ and never once did Kukai suggest in his writings that the goal was to transform one’s corpse into an object of veneration after death, as seen in the phenomenon of sokushinbutsu,” Swanson said.

Then why did this happen? Key to understanding the practice, according to Swanson, is how Kukai was memorialized through legends that were created after his death. These claimed that he “entered into a state of contemplation,” or nyujo, at the end of his life on Mount Koya — suggesting that he never died but was in a state of perpetual meditation.

“The lore that surrounded Kukai’s death and his postmortem transformation into a compassionate, salvific figure captured the imagination of religious practitioners throughout the medieval period and could be seen at the basis of the development of the sokushinbutsu phenomenon,” Swanson said.

In honor of Kukai, the names given to sokushinbutsu of the Mount Yudono lineage all end with “kai,” the Chinese character for ocean.

The practice, however, was outlawed with the Meiji Restoration, when Shinto was separated from Buddhism and declared the official religion of Japan. Dewa Sanzan also moved toward becoming Shinto, and many mummies are thought to have been lost in the ensuing destruction of Buddhist property.

In the 1960s, the remains were cast into the spotlight when a group of academics and scientists led by the late Waseda University professor Kosei Ando began unraveling the mystique surrounding the mummified icons in northern Japan through anatomical and anthropological research. The researchers discovered that many of the mummies were artificially treated for better preservation, although there were no signs of the brain and viscera being removed in most cases. The corpses had been extensively damaged by rats and flies and appeared to have been posthumously smoke-dried.

“The investigation triggered a mummy boom in the 1960s and ’70s that saw television shows and books and magazines featuring the subject, ranging from serious academic studies to those aimed at children’s entertainment,” Hijikata said. The trend would soon die down, however, and by the time Hijikata began reporting for his book in the early ’90s, there was virtually no new literature on the topic.

Now interest in these mysterious monks appears to be making another comeback, thanks to an NHK documentary on sokushinbutsu that ran in 2015 and Haruki Murakami’s 2017 novel, “Killing Commendatore,” which draws on the legend of mummified priests of Dewa as a major plot device.

With these things in mind, I headed up to Tsuruoka to see the “living Buddhas” myself.

Ryusuiji Dainichibo Temple, or simply Dainichibo, lies at the foot of Mount Yudono, around 30 minutes by car from Tsuruoka Station. It may be one of the more tourist-friendly of the temples that enshrine sokushinbutsu. A steady stream of visitors can be seen entering the temple gates — a beautifully weathered wooden structure established during the Kamakura Period (1185–1333) — to pay respects to Shinnyokai, the temple’s resident sokushinbutsu.

“Going to see mummies was a fairly common family event when I was a child,“ recalled Nobuhiko Takayama, my cousin and a life-long Tsuruoka resident, who agreed to drive me around temples housing sokushinbutsu. “Come to think of it, though, it’s sort of a strange choice for a family outing.”

Indeed, it’s a bizarre sensation to sit in front of a withered corpse that departed this world hundreds of years ago.

Shinnyokai, born in 1687 as the oldest son of a farming family in Tsuruoka, is said to have chosen to become a sokushinbutsu as a form of self-sacrifice to end the suffering caused by a major famine at the time. He passed away in 1783 at the age of 96.

Yugaku Endo, the chief priest of Dainichibo and 95th in his line, said that when Shinnyokai was 20, he accidentally spilled night soil, or human excrement collected to be used as fertilizer, on three passing samurai. Enraged, the samurai attacked Shinnyokai, but in the ensuing frenzy Shinnyokai somehow managed to kill all of them. Appalled at what he had done, he sought sanctuary at Dainichibo, or so the story goes.

“Shinnyokai is said to have been a large man,” Endo said. “Even so, could an unarmed commoner kill three samurai on his own?

“Locals, however, recount a different episode. They say he was moving logs on a sled one winter when three children asked for a ride. Being a kind man, he obliged, but one of the children fell off the sled and was killed. Shinnyokai decided to live the life of a monk in atonement for what happened.”

Shinnyokai on the alter of Ryusuiji Dainichibo Temple. ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Like others who became sokushinbutsu, Shinnyokai chose the path of an issei gyonin, or one who dedicates his life to ascetic practices. This mainly involved two types of austerities: mountain confinement, called sanro, and tree-eating austerities, mokujiki-gyo.

Ascetics would spend 1,000-day intervals in Mount Yudono’s Senninzawa (Swamp of Immortals), performing cold-water ablutions and visiting the Yudono Shrine as part of their rigorous training regimen. Many would not survive the freezing winters, when the area would be covered with heavy snow. Those who perished were honored with stone tablets commemorating their challenge.

To begin preparations for self-mummification, the ascetics would adopt a strict diet requiring them to abstain from eating the “five cereals” of rice, barley, wheat, soybeans and adzuki beans (this combination could vary), followed by another set of five plants, typically corn, Japanese millet, foxtail millet, buckwheat and potatoes. Practitioners instead would forage in the mountains for nuts, roots and seeds – a process Endo said was aimed at reducing body fat and muscle.

To inhibit the growth of bacteria, Endo said Shinnyokai is believed to have drunk the toxic sap of urushi, the Chinese lacquer tree related to poison sumac. And to prevent decomposition, he consumed nothing but salt water for over 40 days, emptying the body of any food.

Finally, the ascetic would perform dochu nyujo, or entering deep meditation in the ground.

“A pit 3 meters deep and around 4½ tatami mats wide was dug, and its walls were ensconced with stone,” Endo said. “A wooden coffin would be assembled for the ascetic to enter, which would then be lowered into the chamber. Empty space would be filled with charcoal to remove humidity.”

Once the pit was secured shut, two bamboo tubes would be inserted to funnel down drinking water and act as air vents. Bells would be attached on both ends of one of the tubes, a device used by the ascetic to signal that he was still alive. Once the ringing stopped for good, Endo said, the bamboo tubes would be pulled out to seal the pit. For the next three years and three months, the corpse would be left in the underground cell. On the final day, the body would be unearthed — an instant Buddha if all had gone well.

Of course, success was not guaranteed, and many corpses decomposed during the process. There are also said to be numerous burial mounds of sokushinbutsu yet to be excavated after the practice was banned during the Meiji Era.

Endo said Dainichibo used to enshrine three sokushinbutsu but two were lost to fire when the original temple burned down in 1875, seven years after the Meiji Restoration. Now Shinnyokai sits alone in a glass case, except when he is taken out for a redressing ceremony held every six years.

Sokushinbutsu offer a trove of interesting backstories. Honmyokai entered the ground in 1683 to become the oldest mummy in the Shonai region. He was believed to be a samurai who decided to devote himself to a life of an ascetic after praying at the Swamp of Immortals for the recovery of his master, Lord Sakai, the daimyo of Tsuruoka, who was suffering from an illness.

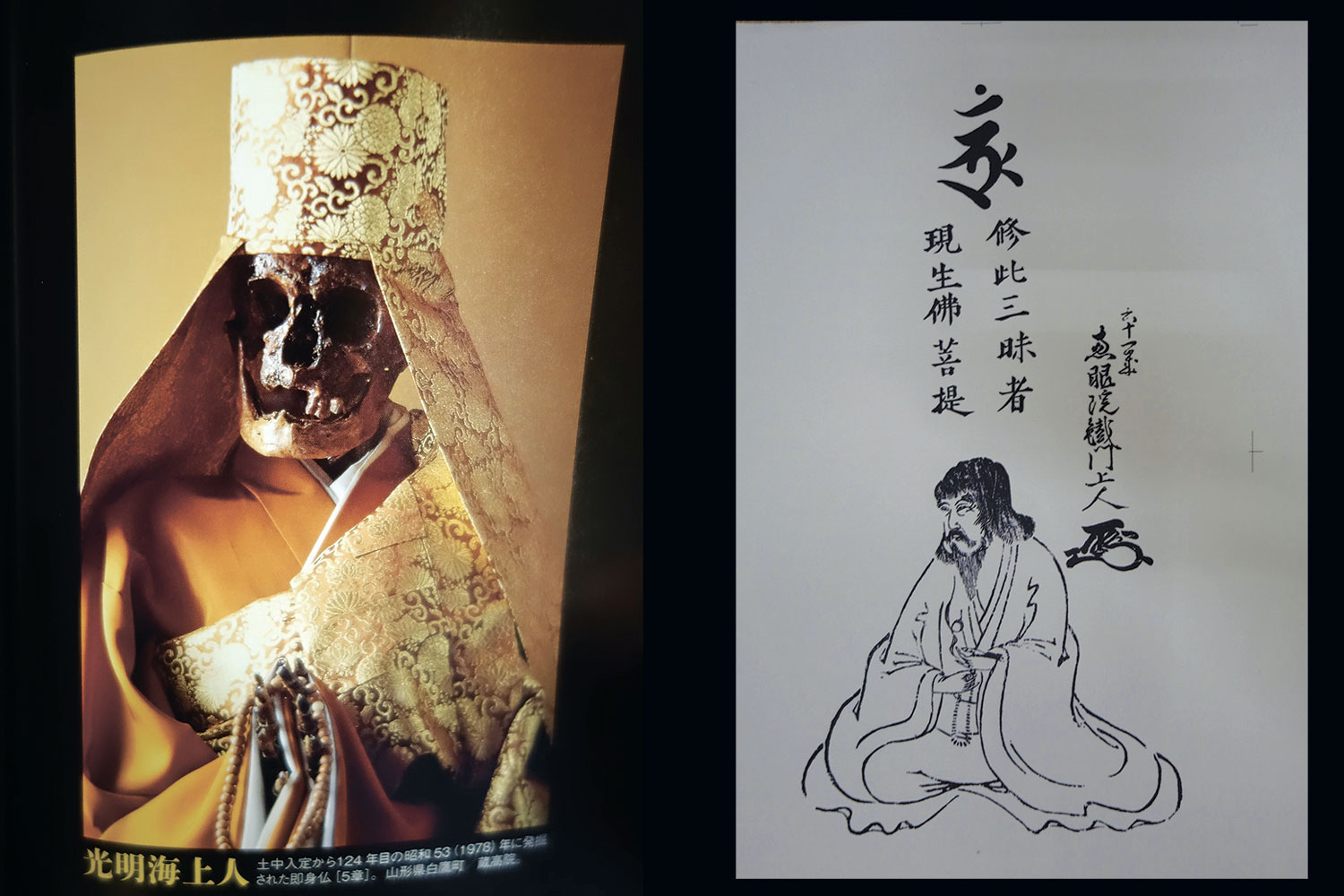

Komyokai, who is said to have been an excellent hunter with perfect aim before entering the priesthood, was discovered in 1978, 124 years after his death. The excavation that took place in the town of Shirataka in Yamagata Prefecture stirred people’s imagination and was widely publicized at the time.

But in terms of the number of colorful episodes and meritorious deeds recorded, no one surpasses Tetsumonkai, whom Hijikata calls the “superstar” of all sokushinbutsu. Born Sunada Tetsu in 1759, he was a river worker who dug wells and floated lumber, and was known for his stormy temperament. According to one account, he killed two samurai after finding them intoxicated on duty and confronting them for negligence. Another account describes him killing a samurai during a fight over a favorite prostitute.

Churenji, the temple where Tetsumonkai is enshrined, gives a somewhat milder account, saying he was angered by the arrogance of an official in charge of river construction and pierced the man’s leg with a fire hook and dragged him around. In any case, Tetsu fled to escape his pursuers and joined the seminary at Churenji in his 20s, where he was given his priestly name.

Records indicate Tetsumonkai was a widely traveled and respected holy man with numerous legends to his name. Once when he was visiting Edo, he witnessed the outbreak of an eye disease that caused great suffering. He proceeded to gorge his left eye out and offered it to the Sumida River in prayer for a cure. Later research found that his left eye is indeed missing, going some way to authenticating the story.

Komei Sato, the head priest of Churenji, has been working to unearth traces of Tetsumonkai through stone monuments commemorating his deeds. Nearly 200 of them have been discovered so far, he said. “There are probably more out there.”

Tetsumonkai’s missionary work centered on the Shonai region, but the monuments show it extended from the Kanto region up through Hokkaido. He is remembered for gathering 10,000 volunteer workers to build a new road through a mountain connecting Kamo Port to Tsuruoka, facilitating trade.

Sato said there are festivals that continue to this day based on Tetsumonkai’s teachings. “He left an enduring impact on many people of that time,” he said.

However, perhaps the most compelling of his legends may be another one involving self-mutilation. At one point, Tetsumonkai is said to have been visited by a prostitute, possibly the same one he fought the samurai for. The woman tried to convince Tetsumonkai to come back to the city with her, but he refused. To prove his resolution and dedication to a life of austerity, he disappeared and shortly returned with a small package for her. Inside were his bloody testicles. He had sliced them off.

The object is said to have made its way around prostitutes of the local pleasure quarters as a good luck charm, and was eventually sent to Nangakuji Temple in Tsuruoka, where it was preserved as a relic. Adding weight to the legend, the genitals are missing from Tetsumonkai’s mummified body.

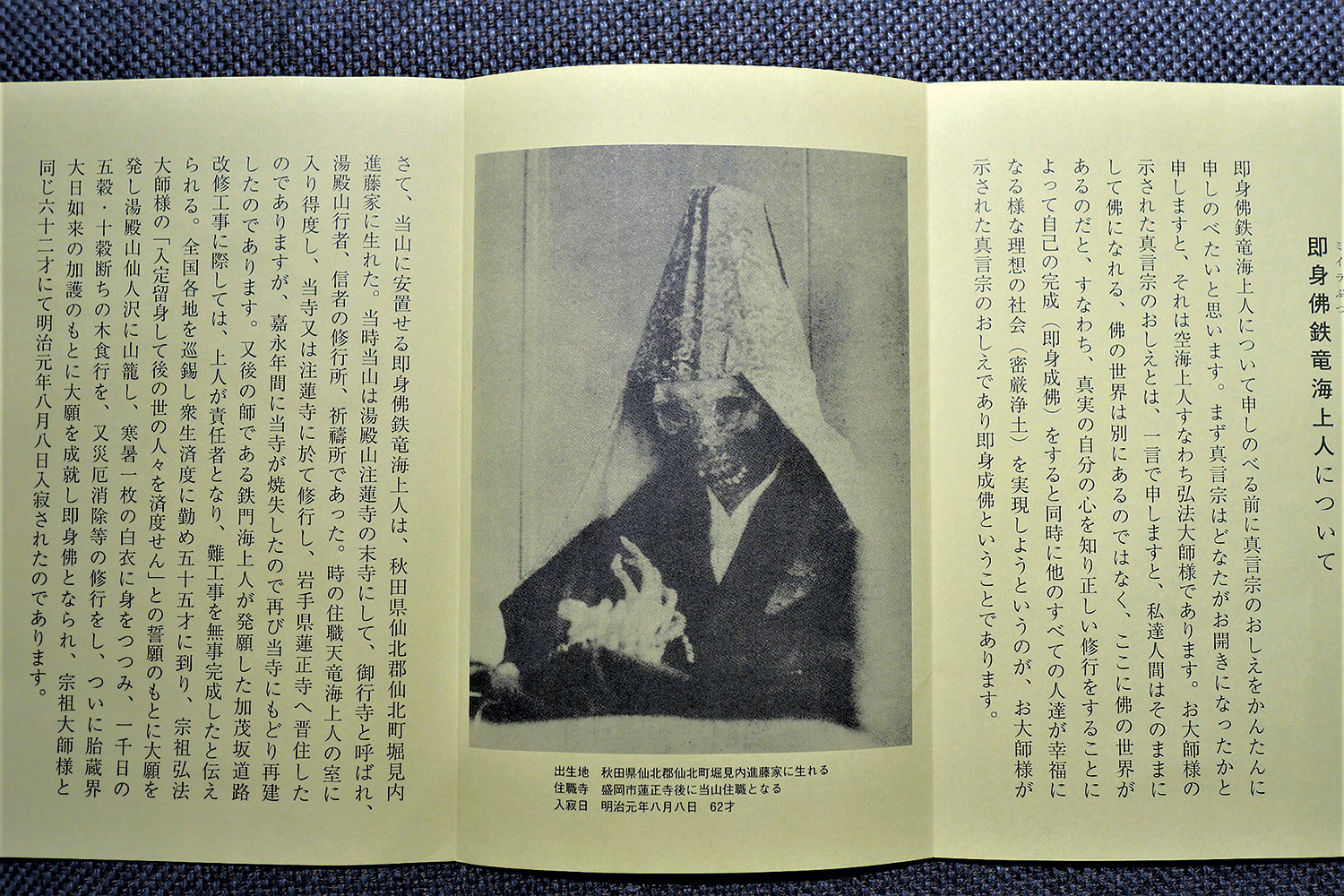

I visited Nangakuji to see Tetsuryukai, one of the newest surviving sokushinbutsu, who is believed to have been mummified at around 1881. Considered Tetsumonkai’s disciple, Tetsuryukai was preparing for self-mummification when the practice was outlawed. He and his followers secretly went ahead with the process, but it wasn’t until 1923 that his existence could be publicized.

One of the visitors asked a question that had also been on my mind: Was the temple really in possession of Tetsumonkai’s testicles? “Yes,” said the head priest’s elderly wife, who was giving us a brief tour of the room where Tetsuryukai is enshrined along with other artifacts. “But they’re not for public viewing.”

Tetsumonkai’s blood group is B, which was also the blood group of the scrotum found in Nangakuji, according to past scientific research. Academics at the time concluded that it was highly likely that the dried testicles belonged to a man who endured extreme physical abuse in the name of ascetic training before being entombed at the age of 71.

It’s easy to dismiss the sokushinbutsu phenomenon as an obscure ritual that died out as the nation marched toward modernization in the late 19th century. However, the mummies provide a fascinating window into the social landscape of pre-modern Japan through their stories of passion, hardships, sacrifice and intense religious fervor culminating in the attainment of Buddha-hood in the flesh.

And they are, in a sense, still very much alive, treated as living, breathing saints by generations of priests and worshippers who have kept the tradition relevant.

To those of us who visit the quiet mummies today, they offer a respite from the seemingly unending trivialities of life.

“They make us think of life and death, and what, if anything, it all means,” Hijikata said. “I’ve come to believe that’s what they’re here for.”