LIFE

Plastic fantastic

Examining the global obsession with Japan’s soft vinyl toys

Maruyama Toys has been making sofubi (soft vinyl toys) since the Showa Era. DAN ORLOWITZ

Inspired by the monsters, robots and folklore of Japanese culture, creators of sofubi — soft vinyl toys — have taken their original plastic creations to new heights.

DAN ORLOWITZ

Staff writer

It’s a cold afternoon in mid-January and, inside a factory operated by Maruyama Toys in a quiet residential area in Tokyo’s Katsushika Ward, Cory Privitera is making sofubi (soft vinyl toys).

In a cramped workspace surrounded by machinery and long sinks, the 33-year-old begins by laying out a series of square plates onto which molds of various shapes and sizes are affixed.

Behind one sink sits a pile of dozens of other molds, some of which are decades old and can still be used today.

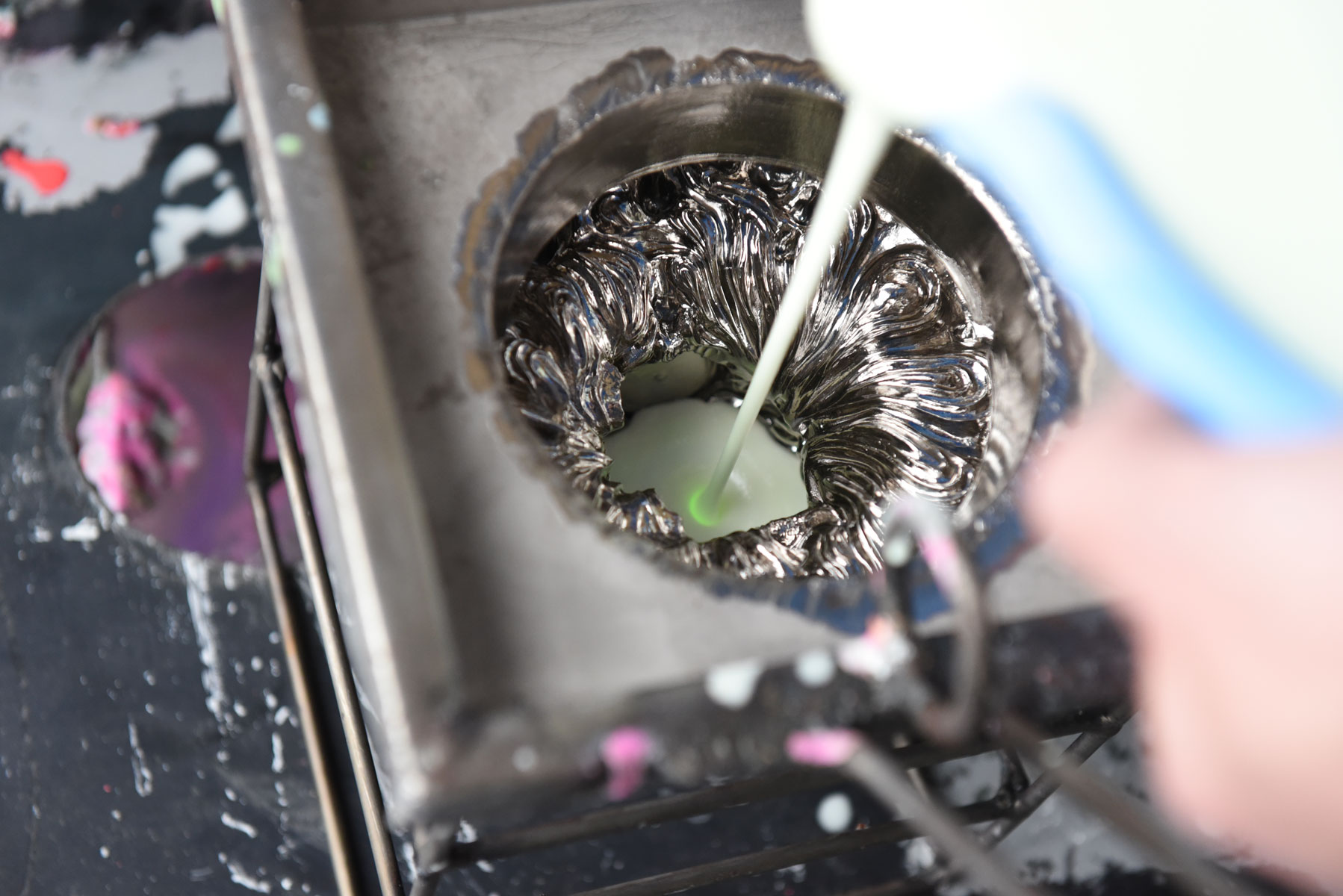

Into these vessels he pours odorless liquid vinyl seasoned with enough glow-in-the-dark powder to cause it to shimmer slightly as it enters the mold. After a few minutes in a vacuum chamber to remove any air bubbles, the molds are relocated to a chemical bath that is 200 degrees Celsius. Following a brief period of “cooking,” surplus vinyl is poured into a container for reuse, while the mold goes back into the bath until the material is fully set.

After a few seconds of cooling down in a water bath comes the “pull” — Privitera yanks seven individual pieces of Wild Hunt, a noseless skeleton of his own creation, from the mold with a pair of heavy-duty tongs. The parts will be trimmed of extra material, assembled and eventually sold, either online or at one of a number of events around the world dedicated to sofubi and other products belonging to what is known as the designer toy scene.

He tosses the parts into a box filled with dozens of others before beginning the process anew.

“The sculpt and wax are done by hand, the joints are made by hand, things are fitted and plated, and every toy is pulled by hand,” Privitera says. “(A lot of) people had a hand in making this thing. It’s super cool to see an idea come to life. It was an illustration and now it’s a thing, and it was done by people, not machines.”

The method is nearly identical to the one used more than 60 years ago, when sofubi were first commercialized and Maruyama Toys opened for business.

“The designs have evolved,” says Yuji Maruyama, president of Maruyama Toys. “We have clients from America who submit what would have been impossible designs in the past. We might make some changes but overall we still get it to work.”

As a child, he painted toys under the watchful eye of his father. Along with his brother and a small team of employees at several Tokyo factories, Maruyama fills orders in countless shapes and sizes from around the world.

“From start to finish, around eight companies are involved in getting the toy from concept to completion,” Maruyama says in the factory’s office area, surrounded by shelves of previously produced toys and boxes full of new orders. “There’s the original sculptor, the silicone mold producers, the wax sculpt producer, the joint-maker, the metal plating specialist, the vinyl toy producers, the colorists and the people who put everything together.”

Privitera’s own interest in the medium as a collector inspired him to move to Japan and take up the craft himself. In addition to pulling vinyl at the factory three days a week, he releases his own toys under the name Science Patrol and serves as a consultant for toy designers.

His whimsical creations, which include a catfish, an interpretation of the mythical kappa (a mischievous amphibious monster) and a larva with the head of a friend of Privitera’s who good-naturedly agreed to toy immortality, have an avid following both within Japan and overseas.

“The toy I am most proud of is Namazu (named after the giant catfish of Japanese mythology that is believed to cause earthquakes), because it was the first toy I made that consistently sold out at shows,” Privitera says. “It was also the first time I ever did my own wax without any type of input from my mentor. It was all done in about two days. The silicone mold was still kind of sticky when I was pouring in the wax — I was just excited to get it out there, really hoping people would like it. People really liked it and I just kept making them.”

In the 1990s and 2000s, independent designers drew inspiration from kaijū such as Godzilla, tokusatsu series such as “Ultraman” and “Kamen Rider,” or the giant robots of “Gundam” and “Macross.” Many overseas sofubi creators invoke Japanese folklore and themes, such as maneki neko (lucky cats) and yōkai (folklore spirits).

“I like old ‘GeGeGe no Kitaro’ — the black-and-white anime are an inspiration,” says Aaron Wilkes, a close friend of Privitera’s who releases toys as Sqdblstr. “I just like the concept of tsukumogami, the idea that an object left for 100 years gets a spirit if it’s not used. … (I like) the idea of making the most of things and using them when you can.”

The designs have evolved. We have clients from America who submit what would have been impossible designs in the past. We might make some changes but overall we still get it to work.

Yuji Maruyama, the president of Maruyama Toys, inherited the company from his father. The company produces sofubi for many of the toy world's biggest companies. DAN ORLOWITZ

Independent artists and facilities such as Maruyama Toys are often connected by larger production companies that coordinate global distribution or character merchandising. One of the most prominent Japanese firms in the industry is Medicom Toy, which was founded by Tatsuhiko “Ryu” Akashi in 1996. Besides its world-famous Be@rbrick series, the company is best known overseas for its work with American designer Kaws, whose creations have graced parks, floated on top of lakes and are on permanent exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Boston.

Closer to home, Medicom works with many of the sofubi scene’s most popular creators, releasing more than 800 products annually. In 2014, the company launched “Vinyl Artist Gacha,” a collaboration with sofubi artists that sees their popular works reimagined as ¥500 capsule-sized toys.

“An artist would appear at an event and sell their toys to tens or even hundreds of fans, and that process repeated itself,” says Akashi, flanked by a veritable museum of Medicom’s most famous releases at the company’s Shibuya Ward headquarters.

“However, there were always people who wanted to buy toys but couldn’t get into the event, or who wanted to go but it was too far away. We wanted to create a way to introduce these artists to a wider group of people,” Akashi says. “A lot of artists have caught big breaks after participating in Vinyl Artist Gacha. It’s good ‘propaganda’ for the sofubi scene and that’s our role.”

Overseas, sofubi and designer toy creators converge at convention centers for weekend-long events such as the Taipei Toy Festival and London Toy Fair. It’s an opportunity for artists to network and for collectors to show off, trade and pounce on limited editions.

While Medicom releases are regular fixtures at these events, the company itself has only recently begun to establish its own booth presence overseas, exhibiting last December for the first time at the Anaheim, California-based DesignerCon.

“The most important thing about (DesignerCon) was being able to experience firsthand what U.S. sofubi fans are interested in, their passion, their relationship with the toys, what they’re looking for,” Akashi says. “They have very strong feelings in regard to ‘classic’ properties. You have to be a bit more careful in how you deal with the market than you would in Asia.”

Despite Japan’s outsized influence on the scene, there have been few domestic events of equal prominence. This has changed somewhat in recent years — toy designers have a sizeable presence at weekend art expos such as Design Festa and are gaining in numbers at Wonder Festival, the biannual marketplace for anime-related figures and garage kits.

One event that has become a mainstay on the toy fan’s calendar is Super Festival, which is held roughly four times a year in Tokyo and Osaka. With affordable table fees and a receptive audience, “SuperFes” has gained a reputation as a proving ground for international artists hoping to reach Japanese collectors.

“What collectors are looking to find is something that represents themselves. When an artist produces a toy, it’s a piece of their soul,” says Los Angeles-based Candie Bolton, the 2017 Designer Toy Awards’ breakthrough artist whose 25-centimeter-tall Bakekujira design won that year’s best soft vinyl award.

“The collector finds something that resonates and also represents them, and they want to keep it and have a display of these things that they like which represent them,” Bolton says.

Sharing a display area with Bolton is Remjie Malham, a Russia-born, Norway-based artist whose psychedelic paint jobs and kaijū-inspired designs have drawn international attention.

“Three years ago I had no idea this was a thing, because in Europe nobody knows anything about this type of media or the subculture of people who collect or produce sofubi,” Malham says. “We try to support each other. We ask each other how we do this (style of painting).”

Next to their booth is Awesome Toy from Hong Kong. The animal-inspired figures on display, with their bright colors and smooth lines, reveal an affection for Showa Era vintage advertisements.

“I want my toys to involve people’s feelings and nostalgia. Each toy is some silly thing or funny thing that makes people happy,” says the toymaker, who is known to his fans only as “A.T.” “In China or Hong Kong (toy events) are more about sales. Here it’s about collectors. Some of the dealers are companies, but some are just collectors bringing out their collections.”

What collectors are looking to find is something that represents themself. When an artist produces a toy, it’s a piece of their soul.

Prices can increase to ¥100,000 or more for larger sculpts, smaller production runs or limited-edition paint jobs. These releases often find their way onto the shelves of secondhand shops or auction sites. The rise of the secondary market, including the presence of occasionally pushy resellers at events, has resulted in friction among some in the community and attempts — with varying success — to put more toys directly into the hands of collectors.

“Most artists don’t like seeing their toys resold,” Bolton says. “They want to sell to a collector and, if anything, have that collector sell to another collector. In general it’s frowned upon to see a toy (at a resale shop) because it means the person who bought it doesn’t really want it.

“But for me, personally, it’s cool to go to Japan and see my toy for sale in a toy store. I don’t really care about the fact that it was resold, I just think it’s cool to see it on the shelf because I never thought it would happen in my lifetime.”

As hype for releases by “famous” artists increases, one common refrain among sofubi artists is the need to expand the scene’s borders as the popularity of designer toys faces what many believe to be an inevitable cooldown.

“A lot of makers are so inwardly focused,” Wilkes says. “They make stuff for the same customers but, as those customers fade out, there’s not a lot of new people entering it. I try to make stuff for me that I’m happy with. For marketability, however, we need new people.”

Beyond a wider range of price points, another oft-suggested idea is that sofubi artists move beyond the medium.

“Some artists get to the point where they expand so far and have a lot of merchandise like clothing and keychains and pins,” Malham says. “It would be nice to see that it can lead people to finding out about the style of art and where it came from.”

Imu Imu Uamou, a variant of Ayako Takagi's popular Uamou character, has been exhibited at museums in Tokyo and Shanghai. YOSHIAKI MIURA

One domestic toy designer has already successfully navigated this path. A daughter of two jewelers, Ayako Takagi has turned her most popular character, Uamou, into accessories, jewelry, clothing and hundreds of sofubi. Her shop, located near the hobbyist mecca of Akihabara, regularly receives visitors from around the world.

“As someone who likes toys and buys them myself, I want to keep prices reasonable,” says Takagi, who first drew Uamou at 14 years old and fully developed the character while studying at London’s Camberwell College of Arts. “I hope I can keep creating characters that anyone can enjoy, regardless of age, gender or nationality.”

Takagi has released capsule-sized versions of Uamou through Medicom and earned praise from Akashi, who is widely regarded as a kingmaker of the scene. While male collectors tend to dominate the floor at shows, it is female creators such as Takagi, Bolton, Malham and others who have been at the vanguard of modern sofubi artists.

“Ayako Takagi, (Negora creator) Konatsu, (Morris creator) Kaori Hinata, they’re all women who are accomplishing a lot and I hope aspiring artists take note,” Akashi says. “Because of what they’ve done, the market has become bigger and new creators can come in. A market that doesn’t welcome newcomers will die out. I want to keep meeting new artists.”