Attracted by the light: Signs for "snack bars" and other establishments are displayed on buildings in Yushima in Tokyo’s Bunkyo Ward. ALEX MARTIN

Watering holes traditionally targeting male customers are changing to reflect the times

ALEX MARTIN

Staff writer

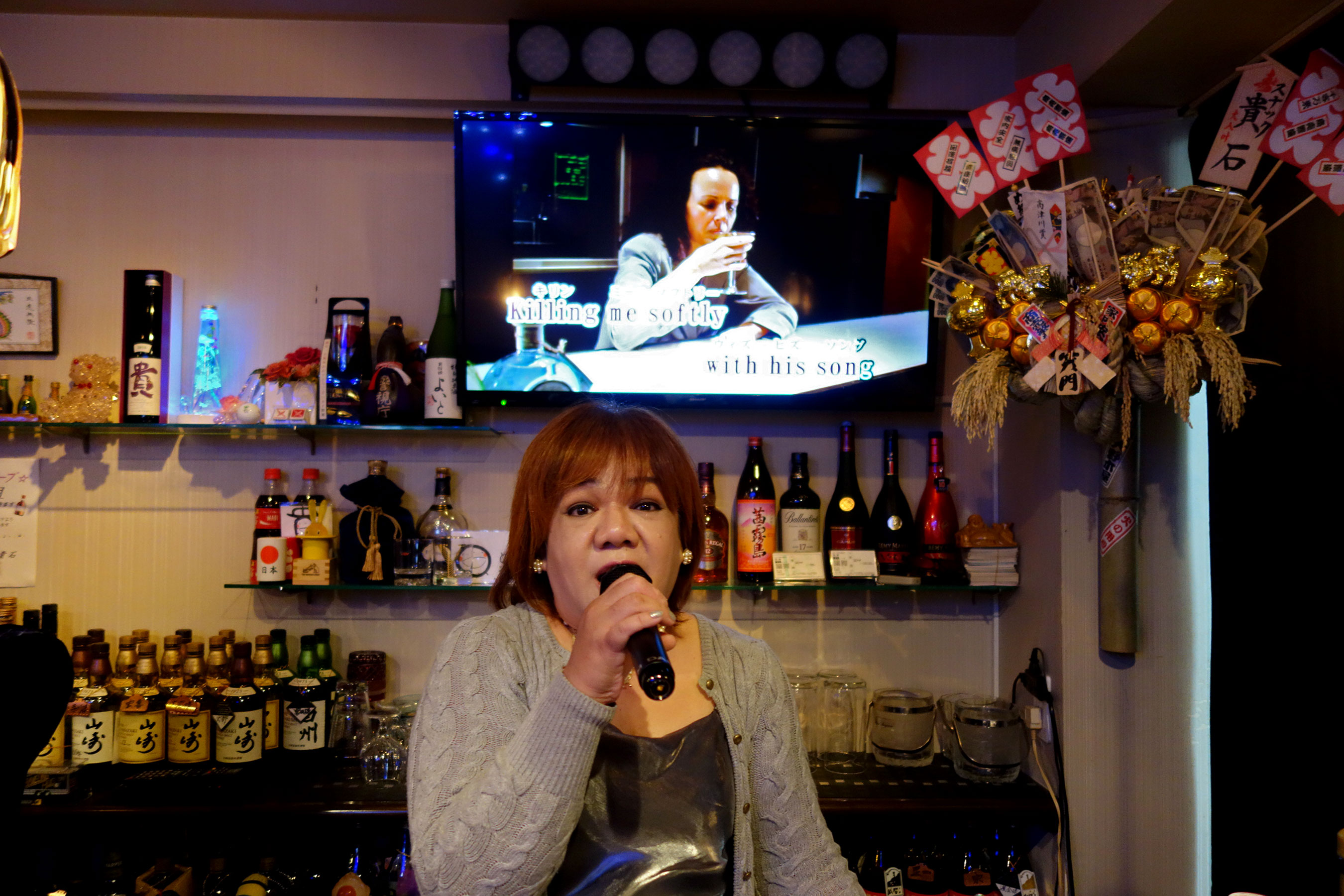

Cigarette smoke wafts across rows of whisky and shōchū bottles with dedicated name tags draped around the necks as an elderly man, microphone in hand, belts out a Showa Era enka tune playing on the karaoke machine.

Another local steps through the heavy door, saluting regulars crowding the bar counter and chatting up Mari Ichikawa, a middle-aged mama-san whose costume tonight is a black, silky gown. Hair carefully curled, face immaculately made up, she hands an oshibori (hot towel) to the latest customer entering her dimly lit domain.

Welcome to the sunakku, or snack bar — a unique and ubiquitous drinking establishment that is a fixture of the Japanese nightlife.

With their distinctive pricing systems, these joints are perhaps best-described as a toned-down, budget version of hostess clubs. For half a century they’ve offered mostly male patrons a whiff of nostalgia, a bit of female comfort and a home away from home.

For the uninitiated, these small, often windowless, bars cluttering narrow, seedy alleys or inhabiting lonely station fronts may seem somewhat intimidating. Once inside, however, visitors can expect to glimpse the role they play as places of communal gathering, somewhat akin to the British pub but in a more intimate setting.

“The number of snack bars has fallen compared to the economically booming bubble years, but there are still an estimated 70,000 of them in Japan — that’s more than there are convenience stores,” says Koichi Taniguchi, a professor of law at Tokyo Metropolitan University.

Outside his regular day job, Taniguchi also heads the Sunakku Research Society, a project funded by the Suntory Foundation to explore the significance of snack bars from various academic perspectives, including history and anthropology.

While snack bars can be found in any big city, Taniguchi says they really thrive in rural areas where, in many cases, they are the only place serving alcohol late into the night.

Born in Beppu, a hot-spring resort in Oita Prefecture, Taniguchi grew up watching his father regularly heading off to snack bars after local gatherings and developed a natural affinity for the establishments, one reason he began researching the topic.

“There’s another face of Japan you can only find through its nightlife,” he says.

And while their numbers have declined, the retro-kitsch ambience that snack bars offer is now resonating with a younger generation.

The snack bar etymology harkens back to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, when the government was tightening regulations on the adult entertainment industry.

Responding to a new law requiring bars to close at midnight, many began serving light meals — “snacks” — to circumvent the regulation and remain open later. Lore has it that some kept an untouched sandwich or two handy in case authorities dropped by to check on whether they were really serving food.

In the 1970s, the invention of karaoke would provide snack bars with what has now become a staple draw. At first a simple eight-track system, it moved on to LaserDisc karaoke in the 1980s, followed by compact discs, DVDs and, finally, online karaoke on demand.

In addition to the karaoke system and the proprietress, the indispensable third element in the Holy Trinity for a snack bar is alcohol — but don’t expect to be served fancy cocktails or craft beer. Snack bars typically only serve beer, whisky and shōchū, the latter being a type of spirit that can be distilled from various materials such as wheat and potatoes. Ice, water and soda are also available.

Pricing fluctuates depending on the size and location of the establishment, but usually involves a table charge of ¥3,000 or so that includes light food. Drinks can be bought by the shot, but regulars often opt to “bottle keep,” buying an entire bottle of liquor from the menu and having whatever is left over from the evening stored at the bar for their next visit. All together a patron might spend anywhere from ¥4,000 to ¥6,000 on a single visit.

Mari Ichikawa, owner of a "snack bar" called Kiseki, serves customers in Kawasaki. ALEX MARTIN

“Our clientele is mostly men around my age,” says Ichikawa, the 58-year-old proprietress of Kiseki, a snack bar in Kawasaki, an industrial city in the greater Tokyo area.

“The kids have grown up and there’s not much to talk about at home with their wives,” she says. “So, instead, they take a hot bath after work and maybe hit a sauna, followed by dinner at a yakitori restaurant or an izakaya tavern before dropping into my place. For many, it has become part of their routine.”

“A costly routine,” quips a man in his 60s with graying hair sitting across the counter, who Ichikawa introduces as a local landowner and her senpai (senior) from high school.

“Shut up, you’re the one who’s always getting plastered,” Ichikawa retorts. “Remember the last time you were so drunk we had to carry you home?”

Ichikawa is a fan of legendary rock singer Eikichi Yazawa, whose poster adorns a wall in the bar. She used to operate a family-owned Chinese eatery with her then-husband for over two decades, followed by another 15 years working in restaurants. Inspired by some of her friends who had started their own establishments, she opened a snack bar named after her two children eight years ago.

“Can you believe I used to be stir-frying food in a wok while I carried a baby on my back?” she says.

Ichikawa employs several other women in their 30s to 50s, including Vilma Carlos Sakai, a 54-year-old Filipina day care worker and singer.

It’s not easy juggling jobs day and night, but Sakai seems relaxed as she exchanges banter with a customer. “People are nice and the mama-san takes good care of us,” she says.

Along with regular snack bars, gāruzu (girls’) bars — in which most of the workers are in their 20s — capitalize on female company. However, the women in these operations often only interact with customers across the counter to avoid infringing the adult entertainment business law and stay open past midnight.

This isn’t the case with certain other entertainment businesses, including the kyabakura, where hostesses sit next to customers and flirt with them.

Upscale hostess clubs in the expensive Ginza district as well as even closer-contact establishments, such as erotic bathhouses called “soaplands” that offer sexual services to customers, need to acquire licenses under the law that limits their operating hours.

“People unfamiliar with snack bars call them dodgy or scary, but it’s nothing like that,” says comedian and snack bar guru Sujitaro Tamabukuro in a statement found on the website of the All Japan Snack Federation, a loosely knit association of snack bars he heads aimed at spreading the cultural allure of the establishment. “I’ve made it my life’s work to visit snack bars across Japan and I can tell you that they are both a relaxing oasis and a place of learning. It’s not an overstatement to say those who don’t know snack bars are missing out on life.”

In a book titled “Nihon no Yoru no Kokyoken” (“Japan’s Nighttime Public Sphere”), edited by Taniguchi and written by members of the Sunakku Research Society, Kiichiro Arai, an associate professor of law at Tokyo Metropolitan University, provides detailed data of snack bars. His findings, based on NTT’s telephone directory from April 2016, show how these establishments are distributed across the nation.

The average number of snack bars in Japan’s roughly 1,900 municipalities is 43, Arai says, while there are 225 with none. His research shows that the most densely served municipalities tend to be found in large cities in western Japan. No. 2 on the list is Sapporo in Hokkaido but the other four members of the top five are Hakata in Fukuoka Prefecture, Hiroshima in Hiroshima Prefecture, Kita Ward in Osaka and Nagasaki in Nagasaki Prefecture.

This gravitation toward large cities in western Japan applies when looking at the number of snack bars per 1,000 people. There exist outliers, however, including Nahari, a small town with a population of around 3,200 in Kochi Prefecture with 6.21 snack bars per population of 1,000, and Kitadaito, a village in Okinawa Prefecture with a population of roughly 600 that measures 4.51 in this scale.

Arai’s studies reveal socioeconomic trends that may shed light on the role these bars play in communities. He says snack bars are rare in suburban commuter towns where residents come home only to sleep, while they’re prevalent in areas with financial difficulties, likely due to their relatively low operating costs. And most interestingly, reported cases of criminal offences are lower in districts with comparatively more snack bars, suggesting these watering holes may be a crime deterrent by providing a sign of life late into the night in otherwise deserted streets.

In terms of the sheer number of snack bars, however, Tokyo remains dominant with 4,938, according to snack bar information site Snackers.jp. They can be found in any large commercial district such as Ueno, Shimbashi, Shinjuku and Ikebukuro, as well as in drinking alleys near most stations.

During the bubble years, numerous buildings specifically designed to house snack bars were constructed, including the River Light Building in Gotanda. Built in 1986, the seven-story structure features a hotel from the third-story up and includes around 50 snack bars and small eateries on the basement, first and second floors.

Masako Akimoto, a short and plump 65-year-old, has been operating her snack bar, Ashitaba, in one of the smaller spaces available in the building for 14 years.

“I spent a year training at a different snack bar as a chi-mama before opening my own,” Akimoto says, referring to a form of address used to describe the hostess who is second in command.

She now runs a bar on her own, serving homemade traditional Japanese dishes, including oden and ohitashi, and occasionally asking customers to buy her small bottles of beer.

“I can down six of these before I get too drunk,” she jokes, while showing an old black-and-white photograph of her days as a bank clerk. “I used to be quite pretty, don’t you think?”

One reason why there are so many snack bars in Japan may be the relatively low setup costs. A bundle of regulations governs where and in what form snack bars can operate, including building codes and approval from the public health and fire departments. That said, from paperwork to renovation, a snack bar can be opened with as little as ¥2 million, giving older, single hostesses such as Akimoto a new line of income once their days of youthful vigor are past.

“There isn’t much to do at home lying around and watching television, so I prefer coming to work,” Akimoto says.

Still, however, times have changed, Akimoto says, and many of her fellow proprietresses have passed away or closed shop. Instead, a new generation appears to be lured by the Showa Era ethos embodied by snack bars, adding a modern twist to attract a younger customer base.

"Snack bars" and izakaya taverns line this narrow drinking alley in Tokyo's Bunkyo Ward. ALEX MARTIN

In 2016, Atsushi Miyawaki, CEO of content production company Note, rented a property just upstairs from Akimoto’s in River Light Building for around ¥150,000 a month and launched the Co-working Snack. The name is derived from how he wanted the bar to serve as an after-hour extension of the co-working space his company manages.

With all the retro charm intact in its decor — the velvet bar stools and black-and-white checkered flooring — Miyawaki installed Wi-Fi and electrical outlets so people can work while sipping their drinks. Men drifting in on a recent Thursday night were not the typical corporate salary men but web designers and others in the IT sector, wearing leather jackets and designer jeans.

And unlike the case with most snack bars, which have a boys’ club feel, a third of the customers were women. That may have something to do with the fact that, instead of hiring a full-time proprietress, Miyawaki recruited young, female freelance writers from writing classes he operates to work behind the counter in shifts.

Saeko Sasaki and Marie Nishibu, both in their late 20s, were tending the bar that evening. Nishibu, who has contributed to publications such as Forbes Japan on topics including health and gender issues, says she has never worked in a snack bar before.

“But if a guy took me to one on our first date, I’d think he knows how to have a good time,” she says as she greets a new guest, her English teacher who seems new to such establishments.

“He was born and raised in Silicon Valley,” Nishibu says, introducing her teacher to others sitting by the counter.

“I’ve been to San Francisco before,” a customer who speaks English responds, starting up a conversation.

A likely attraction to the female customers and “a major difference from the typical snack bar,” says Miyawaki, 45, “is how my place is nonsmoking and doesn’t have a karaoke machine.”

Miyawaki was new to snack bars until several years ago when he began drinking at joints in the River Light Building. He was transfixed by their communal feel.

“At a regular bar you know what to expect, but with snack bars it’s different,” he says. “You don’t know what you’re getting unless you strike up the courage to step through the door and, most of the time, that effort is worth it.”

Miyawaki says snack bars’ popularity has been rekindled in the past couple of years, thanks to some noted celebrities who have openly endorsed the establishments’ allure.

Famous drag queen, singer and television personality Mitz Mangrove, for example, has been operating a women-only snack bar in Tokyo’s upscale Shin-Marunouchi Building for more than a decade, attracting straight women who may otherwise be reluctant to enter a snack bar with a predominantly male clientele.

Miyawaki himself is looking at experimenting how far he can take his snack bar in the age of technology and social media. He wants his place to go fully cashless sometime next year.

“It’s a bold risk and may not work,” he says. “Still, it’s worth a try.”

Despite his innovative approach to his own snack bar, Miyawaki appreciates the coziness of an age-worn snack bar run by a proprietress with years of whisky croak in her voice, offering guidance on anything from lost love to harassing bosses with an authenticity only those who have experienced both sweet and sour can impart.

After finishing his drink at Co-working Snack, Miyawaki heads downstairs to Akimoto’s snack bar, Ashitaba. The proprietress, who is complaining about her failing water heater as she heats up some food in a pot, greets him. Grabbing from the shelf a bottle of Suntory’s Yamazaki with Miyawaki’s name scribbled on it, she pours him a mizuwari (whisky mixed with water).

“Good for you, being so young and managing your own company,” she says half-teasingly, as if talking to her son. Miyawaki laughs and returns a compliment, then asks if her back is alright from the long hours standing behind the counter.

“People seem to be yapping all the time about how snack bars are this and snack bars are that,” Akimoto says. “But it’s all very simple, you know: It’s all about communication.”