A Japan Times reporter tries his hand at writing and performing a comedy routine in front of a bona fide audience

ANDREW McKIRDY

Staff writer

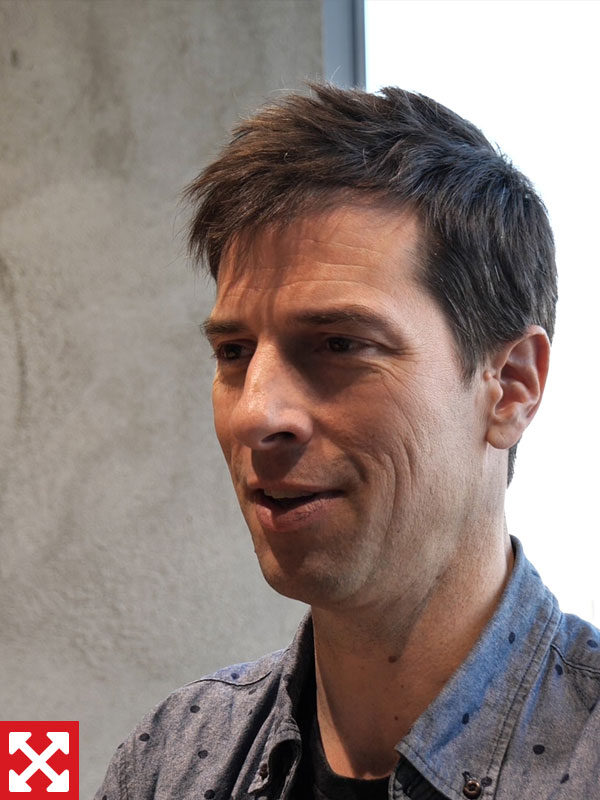

As I stand in the cramped wooden gangway at the side of the stage, going over my lines in a frantic whisper, I am reminded of something that American comedian Patrick Harlan had told me when we first met four months ago.

“The importance of having the language not interfere with the art is huge,” he had said, when I explained that I wanted to write a story about the Japanese art of manzai comedy by going through the experience of writing and performing a routine myself rather than just interviewing comedians. “If everyone is paying attention to your pronunciation or accent, or you’re flubbing your words, then the music is not going to come through. It’s just going to be the sound of you dropping your violin.”

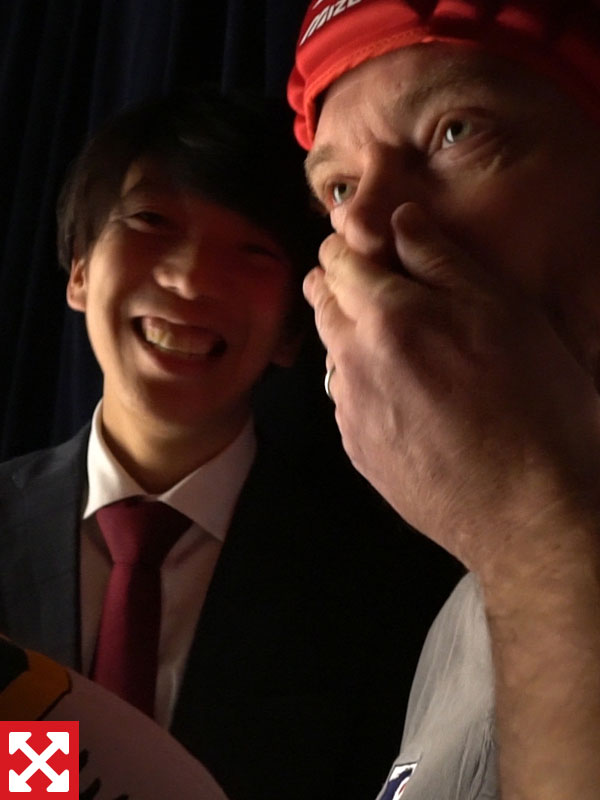

Back in the theater’s wings, I exchange glances with my partner, a 25-year-old named Ryuichiro Nagayama who has agreed to help me with my project. Together we have written a four-minute routine and rehearsed it relentlessly over the course of two months, and now we are going to perform it in front of an audience at a comedy club.

Behind the thin partition, I can hear the sound of applause as the pair preceding us leaves the stage. The emcee calls out our act’s name — Asameshimae (Easy as Pie) — and we step out into the harsh, unforgiving glare of the spotlight.

Manzai is a form of stand-up comedy that can trace its origins back more than 1,000 years to the Heian Period (794-1185). It evolved over the course of the 20th century to become one of Japan’s most popular entertainment forms and is shown widely on TV. It has also served as a launching pad for some of the biggest names in domestic show business.

It can, however, feel somewhat impenetrable to viewers from overseas.

Manzai basically involves two performers (manzaishi): a straight man, known as a tsukkomi, and a funny man, known as a boke. The two trade jokes based on puns, misunderstandings and other wordplay, avoiding controversial topics such as politics, sex or current affairs.

Unlike Western comedy, where an audience is expected to understand the punchline of a joke for itself, the tsukkomi in manzai explains the joke for the audience by correcting the boke’s mistakes. This is done verbally, but is often accompanied by a chastising slap to the boke’s head.

To many Western viewers, this can simply look like two people having a confusing and violent argument. That was the impression Harlan had when he first tried his hand at the craft more than 20 years ago.

He had been in Japan for 3½ years, had made rapid progress in learning Japanese and wanted to do something to further his interest in becoming an actor. He got together with Japanese comedian Makoto Yoshida and formed a duo called Pakkun Makkun, which soon became a regular fixture on national TV.

“It took me about five years to really figure manzai out,” Harlan says upon meeting for the first time at a cafe on a late September afternoon. “Actually, it took me about five years to figure it out at all, then 10 or 20 years to feel like I was getting it at a deeper level. When I first saw it on TV, I thought ‘anybody can do this.’ But I was totally wrong.

“It’s going to be fun for you to experience the joy of realization that it’s a much more challenging art than you expect,” he says. “Thank God I was so naive. I thought I was funny, but I had to totally relearn it. You’re going to have to do that, too, because the things which you expect to be funny are not necessarily funny. The sense of humor is vastly different.”

I am not particularly a fan of manzai, nor do I have any stage experience aside from being involved in a handful of school plays. But I do enjoy comedy, and I am interested in finding out why some things that are funny to Japanese audiences fall flat with Western ones.

My plan is to write a script for a manzai routine using Harlan’s advice, then find a partner willing to help me work it into shape before performing it in front of a paying audience.

Harlan’s interest is piqued when I ask him to be involved, but he does harbor reservations.

“You’re trying to learn an instrument and then play a symphony straight away,” he says, with a knowing smile.

Nevertheless, he agrees to act as my mentor when time permits, and explains the basics before giving me some homework to complete before we meet again.

First, he tells me to get a neta-cho — a notebook that all comedians carry around so they can jot down anything funny that can then be worked up into material.

Harlan also tells me to watch lots of manzai on the internet, explaining that “within manzai there are a thousand types of manzai.”

He asks me to write down about 20 or 30 phrases that a tsukkomi might use to correct a boke’s mistake — such as “you’ve got it the wrong way around” or “that’s too much” — then work my way back to extrapolate what mistake the boke might have made. This sounds simple but is in fact very difficult, and after much frustration I manage to come up with three at most.

I enjoy watching the manzai clips, though, and my eyes are opened to the sheer variety of styles in a genre that I had previously thought was rigidly defined. I begin to notice the quickfire wordplay of Knights, the conversational easiness of Downtown, the physical expressiveness of Non Style and — my favorite — the sudden, explosive violence of Kaminari.

I also begin to have a few ideas of my own, and I write them all down in my brand-new neta-cho. I notice that some of my embryonic jokes share a rugby theme, including one that plays on the similarity between the nickname for the New Zealand national team (the All Blacks) and the Japanese term for the slicked-back hairstyle common among businessmen in the 1980s (all back).

I start to wonder if a rugby theme might also allow me to incorporate some of the physical humor I had enjoyed in Kaminari’s act, and capitalize on the fact that the 2019 Rugby World Cup is going to be held in Japan.

I meet Harlan again to see what he thinks of my ideas. First, I try out some of the jokes he had asked me to take apart and put back together again, including one that plays on the fact that the Japanese word for playing cards (torampu) sounds like the name of the current United States president.

“Is that funny?” I ask.

“It’s a good principle,” he replies.

“But is it funny?”

“It would be funny if done by the right people,” he says. “And that’s going to be an obstacle that you’re going to get frustrated banging up against. You will do the exact same kind of joke that you see working in someone else’s manzai, and it won’t work. But you will find out what kind of jokes and delivery work for you.”

He does, however, like my rugby idea. He is skeptical about whether the audience would know enough about the sport for the jokes to work, but he thinks the fact that I have already come up with some ideas and have found a theme that plays on my appearance as a foreigner makes it a good place to start.

He also puts me in touch with the organizer of a regular comedy night in Tokyo’s Asagaya neighborhood, who goes by the stage name Shishidotch. Shishidotch invites me to his event, called Omoro Shokudo, and says I might be able to find a partner among the acts performing there. He also asks me to perform at the same event on Jan. 6, giving me just over two months to prepare.

I find the venue — a tiny, ramshackle theater called Asagaya Art Space Plot. It has just enough space for an audience of 30, and a stage about 10 centimeters off the ground less than a meter away from the front row.

Some of the performers are milling about outside as I enter, and most appear to be in their early 20s. I catch sight of an Uber Eats delivery box among the detritus leading up to the dressing room. My expectations are not high.

But from the moment the curtain goes up, I am amazed. The quality of each of the 16 acts is far beyond anything I could hope to achieve, and I begin to scour the list of performers in disbelief that I haven’t seen them on TV before. Surely acts like Chomsky, Beiboin, Ton Ton Byoshi and 2 Mai Me Paisley are too big for a venue like this?

The reality becomes clear once the event is over.

“He doesn’t even have enough money to get the train home,” says Shishidotch, pointing at one of the performers. “You should write a story about how hard-up most comedians are.”

Omoro Shokudo, like many small comedy events, operates a system where acts have to pay to perform. Depending on ticket sales, they may be able to get their money back or even make a profit. Many aspiring comedians will do anywhere between 10 to 15 shows a month and still not break even.

It is a far cry from the world of Yoshimoto Kogyo Co., the Osaka-based conglomerate that brought manzai into public consciousness after World War II. It now bestrides the Japanese entertainment industry like a colossus, employing most of the major performers on TV.

😂 😂 😂

I go home impressed — if daunted — and contact some of the performers over the next few days to try to find a partner. Harlan has advised me to play the boke, in part because I will have to remember fewer lines.

“The tsukkomi also has to be the representative of the people,” he says. “He or she has to be the standard Japanese viewer, otherwise they’re not going to represent the audience well enough to explain the joke.”

In the meantime, I start working on my script. Writing in Japanese is, of course, a major challenge, but I also notice how difficult it is to establish a clear, consistent personality for both characters. I feel like I am trying to shoehorn too many ideas in, but after much effort I finish a first draft.

I also find a partner. Nagayama had announced at the Omoro Shokudo event that he and his regular partner were going their separate ways, and he is interested to see where my project might take him.

He explains that he has always loved making people laugh, and used to organize weekly comedy shows at his elementary school when he was 10 years old. He made his public debut when he was 18, at a club in front of about 10 people. He and his partner performed for three minutes, and not a single person laughed.

He was performing about 15 times a month with his most recent partner under the name No Gut Racket, while also working at a Japanese pub. His partner once appeared on the TV show “Getsuyo Kara Yofukashi,” but that is as far as Nagayama has come to the big time.

I show him my script. He is impressed that I have actually been able to produce something, but I can see he is itching to make some changes. I tell him to do whatever he thinks is necessary, but first, before he leaves, he asks me to read through the script with him.

I hadn’t been expecting this. I can see that I won’t get far if I allow embarrassment to get the better of me, so I agree. But my halting, tentative delivery as I read out loud for the first time makes me cringe.

A couple of weeks later, Nagayama gets back in touch. He tells me he has made some changes to the script. I take a look. He has changed practically everything, leaving only the rugby theme and one joke.

I ask to meet him again so he can explain where I went wrong. I tell myself it’s a valuable learning experience, but I can’t help but feel crestfallen.

“The audience doesn’t know anything about the act when the performers come on stage,” he says. “If they don’t understand something, they can’t just go back to an earlier point in the script like we’re doing as we read now. They only know what they can see and hear in front of them. If you give them too much information, they’ll panic and what you’re saying won’t sink in. If you’re dressed as a rugby player and you start talking about something other than rugby, it will be too much for the audience. So I tried to make it more concentrated on rugby.”

Nagayama has cut most of the clutter out of my script and given it more focus. He has also gotten rid of some references he believes a Japanese audience won’t get.

“If you assume that everyone will know something, you’ll end up splitting the audience between people who do know and who don’t know,” he says. “It might sound harsh, but I was always told to assume that the audience are all stupid.”

I take all this on board, but I also ask if he can try to salvage at least some of my jokes. He agrees to take another look, and the next time we meet he has come up with a revised version.

This time we are joined by Harlan, who helps us polish the script further. I notice that Nagayama has changed a joke I wrote comparing a rugby ball to an ostrich egg. In the revised script, it has become a large quail’s egg.

“Why is that funnier than an ostrich egg?” I ask.

“It sounds funnier,” Nagayama says.

“The shape is the same, but it’s so much smaller,” Harlan says. “Most people don’t know what an ostrich egg looks like. Much more Japanese people will know what a quail’s egg looks like.”

Harlan and Nagayama continue to discuss matters of word choice, technique and timing that are just too nuanced for me to understand, and I resign myself to taking a back seat in the creative process. At the end of the day, however, we have a finished script, and now all that is left is for myself and Nagayama to practice performing it.

This is easier said than done. It is a mighty task to memorize a script in a foreign language, but what mystifies me is how I can rattle off some parts easily but get stuck on others. I find myself utterly incapable of saying certain lines, even if they are simpler in structure and content than others that I have no problem with.

Nagayama agrees to tweak some of the lines to make it easier. Going through the script without making any mistakes is still a serious challenge, though, and over the following few weeks I embark on a frenzied mission to nail it. Nagayama, my work colleagues and my wife are all roped in to help.

To give us the experience of performing in front of an audience, we do a trial run at The Japan Times office just before the new year. By this point I know I am capable of delivering my lines flawlessly, but just as likely to make a mess of it. We change into our costumes in a meeting room — rugby gear for me, a sharp suit for Nagayama — and practice as the crowd begins to assemble outside.

Just as we are about to go out, I feel a sudden, overwhelming sense of terror. We walk out to find around 50 people sitting in rows of chairs before us. Nagayama’s voice is louder and shriller than normal as he addresses the audience, and while I am noticing this — in a dazed and somewhat detached state — I realize we have already started.

Somehow I manage to deliver my opening lines, and then something unexpected happens: The audience laughs, and I feel a surge of encouragement.

Strangely, for someone learning how to become a comedian, this isn’t something I had previously considered. I had been concentrating so much on remembering my lines that I hadn’t even thought about how the audience’s reaction would affect me. But it does. With every laugh I feel more confident, and with every silence I shrink a little.

We get through it without any major mistakes, and retire to the meeting room to pick over the performance with Harlan.

“It was a lot better than I expected,” he says. “But the things I noticed the most were the fact that you were shuffling around and the fact that it was difficult to make out what you were saying.”

This is a fair comment. The prospect of making a spectacle of myself in front of my colleagues had put something of a handbrake on my performance, especially when the script called for me to do an approximation of the haka — the traditional Maori war dance performed by the New Zealand rugby team.

“You’ve got to throw away that sense of shame and go all out on that one,” says Harlan, who is unable to come to the Jan. 6 show. “Because if you’re embarrassed, the audience is going to be embarrassed for you.”

I vow to turn the volume up to 11, and spend the new year holiday trying not to think too much about it.

😂 😂 😂

When Jan. 6 comes, I arrive at the venue in good time and head to a small nearby park with Nagayama to rehearse. Soon, we are joined by other acts with the same thing in mind. I find it difficult to concentrate knowing how the scene must look to passers-by — a park full of men squabbling together in pairs, occasionally punctuated by bizarre gestures.

Eventually we return to the venue to get changed, knowing that we are the third of the 10 acts in the running order. As the time draws closer, we make our way to the narrow, enclosed gangway at the side of the stage and whisper one or two final rehearsals as the acts in front of us take their turn.

Our name is called, and we walk out onto the stage. We are greeted by immediate howls of laughter.

I am taken aback, insulted even, when I realize they are laughing at my appearance — a bearded Scotsman in full rugby gear, complete with red scrum cap. Then I remember something Harlan had told me: “As long as they’re laughing, it’s a success.”

We begin the routine and I throw everything into it, hamming it up and delivering the lines at top volume. The laughs seem to come less frequently than at our Japan Times show, but we get them in the right places and the audience appears to enjoy it. I mess up a line that takes the wind out of one joke’s sails, but overall it goes as well as I could have hoped for.

We leave the stage and walk back along the gangway past the acts still waiting to come on. The contrast in body language between our relieved swagger and their hunched tension is striking.

We allow ourselves a moment of congratulation before emcee Shishidotch calls us back to the stage to conduct a short interview with the night’s first five acts. This is also his moment to reveal that I am not, in fact, a seasoned comedian but a journalist. I savor the gasps of astonishment that accompany this revelation.

The night has been a success, and Nagayama is also satisfied with his involvement.

“It’s been a learning experience for me, working on a routine with someone who isn’t Japanese,” he says. “I think this will stand me in good stead for the future.”

But the show may not be over just yet for Asameshimae. Shishidotch has invited us to perform the same routine one more time at a larger venue in March, and, although my initial instinct is to say no, I have enjoyed it so much that I am tempted.

I am still unsure why some things are funny to Japanese viewers but not to Westerners, but after four months of trying to find out, I think I now have a slightly better understanding.

If I knew the magic formula, though, I would already be on TV.