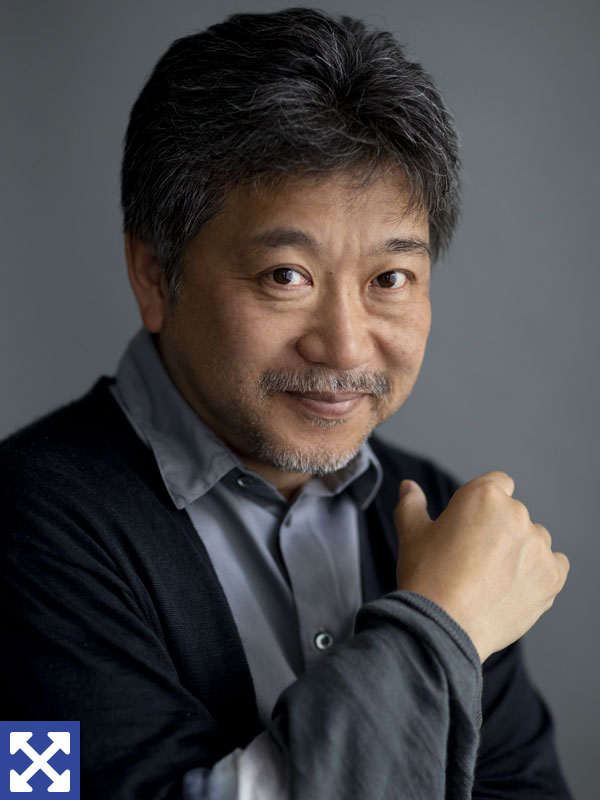

International touch: Director Hirokazu Kore-eda poses for a portrait in Tokyo’s Minami-Aoyama district in September. MARTIN HOLTKAMP

Award-winning director makes rare move overseas with latest release in a bid to experience various types of filmmaking

MARK SCHILLING

Contributing writer

Many Japanese filmmakers talk about wanting to work abroad and dozens have done it, but the number of Japanese master directors who have made great films with only foreign actors in overseas locations trends toward zero.

Thus, Hirokazu Kore-eda, winner of the Cannes Palme d’Or last year for his dark family drama, “Shoplifters,” not only stepped out of his professional comfort zone but also challenged a local industry jinx by making “The Truth,” a drama shot in France with an international cast and not a word of dialogue in Japanese.

The film, about the clash between an elderly actress (Catherine Deneuve) and her scriptwriter daughter (Juliette Binoche) over the former’s largely fabricated memoir, opened this year’s Venice Film Festival, where years earlier Kore-eda had his first international triumph with his 1995 feature debut, “Maborosi.” “The Truth” later screened at the Toronto International Film Festival, North America’s largest and most important showcase for new films.

“I was a bit relieved,” says Kore-eda in an interview at the office of the film’s Japanese distributor. “The audiences laughed a lot at both screenings and, judging from their reaction, the film cleared the language hurdle.”

He claims not to be bothered by the critics, who have been divided over “The Truth.” Its current Rotten Tomatoes score is 75 percent — the lowest of any Kore-eda film to date. “That’s up to them,” Kore-eda says. “I don’t need to concern myself with that sort of thing.”

Kore-eda initially had no strong desire to work abroad. “First of all, I only speak Japanese,” he says. However, he and Binoche discussed working together while both were participating in a 2011 talk event.

Also, while at the French Film Festival in Japan, which is held annually in Yokohama, Kore-eda was told by fellow director Francois Ozon that he should try filming in France.

“He said I’d be successful there,” Kore-eda recalls with a grin. Then his 2013 film, “Like Father, Like Son,” became a hit with French audiences. “I felt that the demographic for my films there had definitely expanded,” he says. “It was a big plus for me.”

Yet another plus: French backers came forward with financing. “So all the conditions were right (for making a film in France),” he says.

However, Kore-eda adds he also had no intention of making a “French film.”

“I’m often asked that,” he says. “But even when I shoot in Japan, I never think of making a ‘Japanese film.’ I’m only conscious of shooting a film, period. And I felt that would also be the best way to make (“The Truth”). The only idea I had was to make a good film — the same as always.”

But Kore-eda felt that shooting in an unfamiliar foreign locale would be “difficult and scary.”

“For me that was harder to deal with than the language problem,” he says. “I didn’t want to end up with a mishmash of scenery like picture postcards or with a tourist’s view of Paris. I thought carefully about how to avoid that.”

His solution was to limit his locations, with 70 percent of the film being shot in the elegant house of Deneuve’s character in Paris. “I felt that was the best way to go,” he says.

Kore-eda also wanted to take a slightly more comedic approach than found in “Shoplifters,” with its dark story of life on society’s margins.

“That’s my natural way of working,” he says. “Looking back on the 10-plus films I’ve made to date, after filming something heavy, I usually feel I want to do something a little lighter. I’ve got to recharge my internal batteries once in a while by doing something different. I’m not so attracted to the ‘Kore-eda-like’ stuff that people want from me and I don’t really want to keep working within that box.”

Exemplifying that lighter approach is Deneuve as the actress, Fabienne. Despite her tart tongue, diva manner and many faults (beginning with her lies in the memoir), she is direct and natural in ways funny and sympathetic. Critics have singled out Deneuve’s performance as her best in years.

“We got along well,” Kore-eda says. “More than preparing beforehand, she’s the type who comes to the set and pours all her energy into what she is feeling at the moment. I thought that was a great way to work.”

Kore-eda adds that he and Deneuve began detailed discussions a year before the shoot. They also rehearsed extensively in the studio. “We had a mutual understanding of what we wanted to film,” he says.

Director Hirokazu Kore-eda won the Palme d'Or for "Shoplifters" at the Cannes Film Festival in 2018. KYODO

When I say her character reminds me of similarly salty mother figures played by the late Kirin Kiki in some of Kore-eda’s best films, he agrees. “As characters they overlap in some ways,” he says. “But (Deneuve and Kiki) were totally different in the way they prepared. Deneuve was the type who asks, ‘Who needs role preparation?’”

The story, I say, reminds me of the first film that Kiki did with Kore-eda: “Still Walking,” a film about the uneasy reunion of a dysfunctional family. In “The Truth,” a scriptwriter named Lumir (Binoche) reluctantly travels from her home in New York with her actor husband (Ethan Hawke) and young daughter (Clementine Grenier) to visit her mother in Paris.

“True, they’re both about homecomings,” Kore-eda says. At the same time, however, Kore-eda adds the new film has “none of the personal experiences” that he has incorporated into his Japanese family dramas, such as the housing complex in “After the Storm” where Kore-eda had actually lived with his own family.

“Instead, I put a lot of stress on things like interviews with Deneuve and Binoche,” he says. “Using their lives as a reference, I wrote the script.”

Noting that more Japanese directors are now working abroad — including such well-known names as Kiyoshi Kurosawa (“To the Ends of the Earth”) and Sion Sono (“Prisoners of the Ghostland”) — I ask Kore-eda if he sees a trend toward internationalization in the Japanese film industry.

“I don’t think (making films in foreign locations) will become a trend,” he replies. “There won’t be any sudden increase. Also, we haven’t yet hit the limit in terms of what we can produce just for the domestic market. That limit is still in the future. I do want to experience various types of filmmaking, though. That doesn’t mean that I’m shifting the base of my operations abroad because I can’t make what I want to make in Japan. There’s still a lot that I want to do in this country.”

But not at the moment, he adds. “I want to rest a bit,” he says. “I’ve been shooting too much, one thing after the other. How long will I take off I wonder? Well, for the rest of this year I’m not going anywhere.”

University students look at a poster for Hirokazu Kore-eda's "Shoplifters" in June 2018. KYODO

Kore-eda has not been idle, however. He’s written two nonfiction volumes about the filmmaking process and put together a collection of interviews with Kirin Kiki to commemorate the first anniversary of her death at age 75 on Sept. 15 of last year. “But both (projects) are done now,” he says. “I’ve just finished all my summer homework (laughs) so I’m not going to write anything for a while. Every day now, I’m watching films that have nothing to do with work.”

The 57-year-old director is also thinking about the films he has left — and how he wants to make them. One long-considered project is another family drama with Hiroshi Abe, who starred as the drifting adult son to a distant physician father in “Still Walking” and as the degenerate gambler with a demanding ex-wife in “After the Storm.” “I’ll do it when Abe gets older,” says Kore-eda. “If I shoot six more films, that will be 20 as a director. That’s a kind of goal of mine. (Quentin) Tarantino said he would quit after 10 films. I won’t quit, but I want to reach 20. If I keep shooting the way I do now, it will get tough once I pass the age of 70, though. I’ll try to shoot what I want to shoot while I still have the physical strength.”

As a proven hit-maker in Japan — “Shoplifters” was the fourth-highest-earning Japanese film last year, taking ¥4.55 billion at the box office — can’t he make just about anything he wants? “I can’t,” he says. “Not every project of mine goes through. Only about half get the green light.”

How about something like Netflix for projects that get the thumbs down? “Maybe someday I’ll do something like Netflix,” he says. “For now, though, only feature films appeal to me.”

His company Bunbuku Kore-eda is also producing films by younger directors, such as the five who contributed to the 2018 sci-fi omnibus “Ten Years Japan,” on which he served as executive producer.

The Bunbuku staff currently includes directors Miwa Nishikawa (“The Long Excuse”) and Mami Sunada (“The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness”) and seven young directors-in-training. “It’s pretty busy now because Nishikawa has just started making a new film,” Kore-eda says. “She’s using all of one floor and recruiting her staff.”

Nurturing young directors, he adds, “is something I should do but it’s different from a mission. It’s just good for me to have young creators around.”

“It’s all about me,” he says, laughing.

Out in the wider world, though, he is now regarded as a master — his generation’s version of Akira Kurosawa or Yasujiro Ozu. Does that label feel strange to him?

“It can’t be helped,” he says, “but it is uncomfortable. When I go to Venice now, they call me ‘maestro.’ What’s a ‘maestro,’ I think. A guy at Fuji TV I’ve known since my 20s calls me ‘kyoshō’ (master) half joking. But now they’re writing about me as a ‘master’ in magazines and elsewhere — and they’re not joking. I want them to quit it. It makes me feel a little weird.”

10 of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s best cinematic works

In a directing career that goes back to 1991, Hirokazu Kore-eda has made everything from feature films (14 to date) to documentaries, TV commercials and music videos. Here is a personal top 10, in chronological order:

‘Maborosi’ (1995)

Kore-eda’s first fiction feature about a young woman (Makiko Esumi) in mourning after losing her husband to an unexplained suicide is shot in muted colors, with the mood of a waking dream. But for all its tamped-down emotions, the film is eloquent about the pain of remembrance, the ache of longing and the fragility of life.

‘Without Memory’ (1996)

A heart-breaking but completely unsentimental documentary about a man who has lost the ability to form new memories. With objectivity, patience and sympathy, Kore-eda investigates the centrality of memory to human life — a key theme of his fiction films.

‘After Life’ (1999)

A fantasy about a way station where the newly dead choose one memory to take with them to the afterlife. Made with fictional and documentary footage, the film is by turns funny and disturbing, while provoking reflection and, just possibly, a few regrets.

‘Nobody Knows’ (2004)

Based on a true incident, this drama about a mother who abandons her three children in modern-day Tokyo has a documentary-like naturalness and a deftly structured, if seemingly plotless, story. Utterly persuasive, quietly devastating.

‘Still Walking’ (2008)

The first of Kore-eda’s collaborations with Kirin Kiki, this family drama depicts the uneasy homecoming of an unemployed adult son (Hiroshi Abe) to his disapproving physician father (Yoshio Harada) and down-to-earth mother (Kiki). The film’s bubbly, naturalistic surface is periodically broken by moments of illuminating revelation, like firecrackers going off with a flash and a bang.

‘I Wish’ (2011)

Perhaps the most accessible Kore-eda for newbies, this comedy centers on two boys — one living with his mother, the other with his father — who plot to bring their divorced parents back together. Made with humor and charm, as well as unforced observations into the way kids actually think and behave, it’s “Tom Sawyer” comes to Kyushu.

‘Like Father, Like Son’ (2013)

This drama about two boys who were switched at birth — one fathered by an elite salaryman (Masaharu Fukuyama), the other by a non-elite small-store owner (Lily Franky) — addresses the question of what it means to be a father in a society that values status over human relations. Many small, piercing epiphanies, no big, obvious message.

‘The Third Murder’ (2017)

This twisty legal drama about a twice-convicted killer (Koji Yakusho) on trial for a third murder is incisive about both the Japanese legal system, with its 99 percent conviction rate, and the mysteries of the human heart, including that of its slick, morally conflicted, lawyer hero (Masaharu Fukuyama).

‘Shoplifters’ (2018)

Winner of the Cannes Palme d’Or, this drama about an ersatz family living by petty crime is packed with well-plotted revelations. For all its grifts and disguises, however, it is ultimately more poignant than clever, as the plain humanity of its “family” emerges from the moral gloom.

‘The Truth’ (2019)

A set-in-Paris family comedy/drama about a scriptwriter (Juliette Binoche) butting heads with her actress mother (Catherine Deneuve) over the latter’s filed-with-falsehoods memoir. Call it Kore-eda-lite, this film features a bravura performance by Deneuve that, in its humor, energy, skill and wisdom, ranks among the best in Kore-eda’s oeuvre.