NEWS

Kawasaki confrontsits gentrification

After successfully luring factories of big-name companies, Kawasaki morphed into a booming manufacturing hub, and ultimately a linchpin of the Keihin industrial region. REUTERS

Urban renewal of industrial powerhouse clashes with its history

TOMOHIRO OSAKI

Staff writer

Surrounded by bustling downtown streets, shopping malls and high-rises, Kawasaki Station and its vicinity are, on the surface, paragons of urban development.

Just a short distance away, however, this veneer of prosperity gives way to an eerie quiet that persists in the underbelly of Kawasaki, a former hub for factories and manual laborers with a long history of battling poverty, pollution and racial discrimination.

A walk northward from the station takes one to a notorious riverbank of Tama River, where a 13-year-old schoolboy was viciously slain by a gang of local juveniles on a freezing February night five years ago. Because the ringleader behind the lynching was a Filipino Japanese, the case at the time spotlighted anew the difficulties of fitting in for children with foreign backgrounds. It also gave ammunition to xenophobic rallies that had begun surfacing in Kawasaki a few years before.

South of the station, meanwhile, lies Nisshincho, a well-known doyagai (flophouse district) inhabited by many elderly men, most of them without any family, scraping by on welfare. Memories remain fresh here of a raging fire that engulfed two of these low-rent hotels in May 2015, killing elderly lodgers thought to have drifted to the area after becoming alienated from mainstream society.

Freelance writer Ryo Isobe, who has authored the book “Rupo Kawasaki” (“Reportage on Kawasaki”), says he sees both the Tama River lynching and the Nisshincho fire as representing the epitome of social woes born of modern Japan, which itself is struggling to acclimate to a rise in foreign residents and cope with more and more lonely deaths of the elderly.

“If you look at it, Kawasaki Station and its surrounding areas are so beautifully redeveloped,” Isobe said in a recent interview.

“But just a casual walk away from the station will allow you to see the kind of dark side of Japan that has increasingly been overshadowed by the nation’s effort to spruce up its image ahead of the Tokyo Olympics,” he added.

While some residents welcome the prospect of their city attaining a more sophisticated image, others express unease over what they see as an attempt to marginalize the manual laborers who once formed the backbone of Kawasaki’s prosperity and simply smooth over its less respectable parts in the name of regeneration.

Industrial juggernaut

Kawasaki is a city in the greater Tokyo area flanking the capital’s Ota and Setagaya wards, with the Tama River in between. It has a population of over 1.5 million, ranking sixth among the 20 major cities outside of the capital. Statistics show that Kawasaki saw the greatest population growth — 29.22 percent — between 1990 to 2018 among the 20 cities.

In one of the most visible signs of the city’s urban renewal, Kawasaki Station was revamped in 2006 with the opening of a large-scale shopping mall called Lazona Kawasaki Plaza that now adjoins the station’s west side, occupying an area where a Toshiba factory used to sit. The area around JR Musashi-Kosugi Station, which is also located in the city, has carved out a reputation as one of the most sought-after commuter towns near Tokyo due to the construction of upscale high-rise condominiums.

But despite these steps toward redevelopment, a down-at-heel atmosphere is still discernible in the southern part of the city that consists mainly of Kawasaki Ward — the heart of the city’s identity as an industrial powerhouse.

An area equivalent to today’s Kawasaki Ward flourished toward the end of the Meiji Era (1868-1912) by aggressively luring factories, including those operated by the companies known today as Toshiba Corp., JFE Steel and Ajinomoto Co. This helped Kawasaki morph into a booming manufacturing hub, and ultimately a linchpin of the Keihin industrial region.

At the same time, an inflow of laborers from across the nation, coupled with the subsequent spike in manufacturing demand linked to the 1950-1953 Korean War, sped up Kawasaki’s transformation into a nightlife mecca rife with seedy bars, gambling dens and brothels.

“When there is booze, gambling and prostitution, you would naturally have certain kinds of people running these businesses — most commonly yakuza,” Isobe said, adding that Kawasaki has consequently been recognized as a “very important place for yakuza society.”

The reign of these criminal organizations, he said, has created a rigid “pyramid of outlaws” that has often led to local juvenile delinquents and thugs being systematically absorbed into the yakuza.

“I think it’s this structure that has partly contributed to what we perceive to be the disorderliness of Kawasaki,” Isobe said.

The writer also claimed that Kawasaki’s proximity to Tokyo made it the victim of “inner-city” problems, including poverty, noting its postwar land reclamation spree was partly aimed at compensating for downtown Tokyo’s lack of space for more factories.

“So in a way, Tokyo’s burdens were imposed on Kawasaki,” he said.

Today, unlike the south, which is widely seen as working class, the city’s northern part has grown in popularity as a family-friendly bedroom community punctuated by high-class residential areas. A quick walk from Shin-Yurigaoka Station in Kawasaki’s Asao Ward offers a glimpse of this middle-class suburbia, with house after house along a well-maintained road boasting immaculate yards.

In fact, such is the disconnect between the north and south that Hyogo Prefecture native Marina Kawakami, 30, says she didn’t realize Shin-Yurigaoka was part of Kawasaki until after her recent move to the area.

“It wasn’t until I was doing some paperwork at the Asao Ward Office that I noticed I had become a Kawasaki citizen,” she said. “My first thought was, ‘Jeez, that Kawasaki?’” she said, noting how she recalled once hearing a TV commentator describe the city as an “unsafe” factory zone.

“So whenever people ask me where I live, I make a point of saying I live in Shin-Yurigaoka, not Kawasaki.”

Forgotten town

Southern Kawasaki’s vulnerability to poverty can be seen when the numbers are crunched.

Among the seven wards comprising the city, the number of households on welfare assistance was by far the largest in Kawasaki Ward, at 8,293, or about 35 percent of the total, as of January. This compares with the 1,459 households in the more affluent Asao Ward. Kawasaki Ward was also home to the greatest number of recipients of the child-rearing allowances doled out to single-parent families, at 1,431 as of March 2019, a figure higher than the citywide average of 888.

Nowhere is the notion of the “forgotten south” perhaps better epitomized than in Ikegamicho, a small town situated adjacent to a seaside factory zone that sits on reclaimed land and is home to JFE Steel and other manufacturers and mills.

Ikegamicho, the bulk of which is owned by JFE Steel, is distinguished by its intricate web of narrow alleys dotted with run-down houses.

In 1912, Nihon Kokan, a predecessor of JFE, started building plants on a reclaimed area near Ikegamicho, and in 1939 purchased part of what now constitutes the town, according to JFE official Hisayoshi Kimura. Both Kawasaki and JFE said there are no official records kept of how this peculiar town came into being, but it is widely believed that Korean laborers recruited by Nihon Kokan and their families started building shacks in what would become Ikegamicho after World War II.

Hiroi Honda, a longtime resident of Ikegamicho, said she still vividly recalls the horror she felt upon seeing the area when she relocated from Tokyo to the neighborhood in 1966 with her Zainichi ethnic Korean husband.

What unfolded before her eyes was a thick fog of smoke and iron powder spewing from the nearby Nihon Kokan plants, making it impossible for her to discern anything more than a few meters away.

“Back then residents here were sharing a water tap outside, and everyone who wanted to wash rice had to use an umbrella to shield against the smoke as they stepped outside. I couldn’t even do the laundry,” Honda, now 74, recalls. She says she briefly suffered asthma because of the pollution.

“I was shocked to learn that a place that horrible even existed in Japan.”

Fast-forward to 2020 and the contaminated air is at least no longer that visible in Ikegamicho. But the town remains something of a maze, with a cluster of houses blocking the entry of emergency vehicles, raising safety concerns in the event of a fire. It has also suffered an exodus of youth, replaced instead by a growing population of non-Japanese residents seeking low-rent dwellings.

While Kawasaki as a whole has changed dramatically, the wave of gentrification that has hit the city has yet to reach Ikegamicho, Honda says.

“We are left behind and forgotten,” she said.

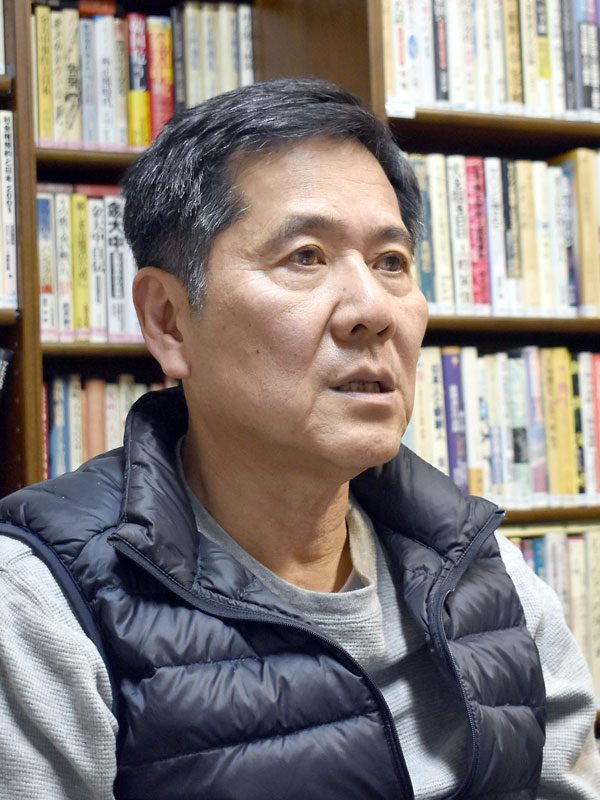

Tomohito Miura, who has dedicated most of his adult life to fighting discrimination against Zainichi Koreans at Fureaikan, a community center near Ikegamicho, confesses to mixed feelings about the urban renewal sprucing up Kawasaki.

He is concerned that the current shift toward gentrification might simply whitewash the history of the hard work manual laborers put into making Kawasaki an industrial powerhouse — and the sacrifices they paid as they bore the brunt of the city’s pollution problem.

“It’s these people who now make up southern Kawasaki’s elderly population, and I think they are our greatest asset,” he said.

Still, Miura says he doesn’t entirely oppose the redevelopment underway.

“But,” he said, “if this urban development thing is going to be something that’s about sugarcoating our past and merely pursuing the cosmetic beauty of our town, I wouldn’t find anything attractive about that,” he said.

“I hope that our identity as a town of sweat-drenched laborers who worked their butts off to support the prosperity of Kawasaki — and Japan — will eventually be considered as something we can be proud of, not in denial of.”

Tomohito Miura TOMOHIRO OSAKI

Kawasaki’s industrial area is located close to Haneda Airport. BLOOMBERG

Moving on

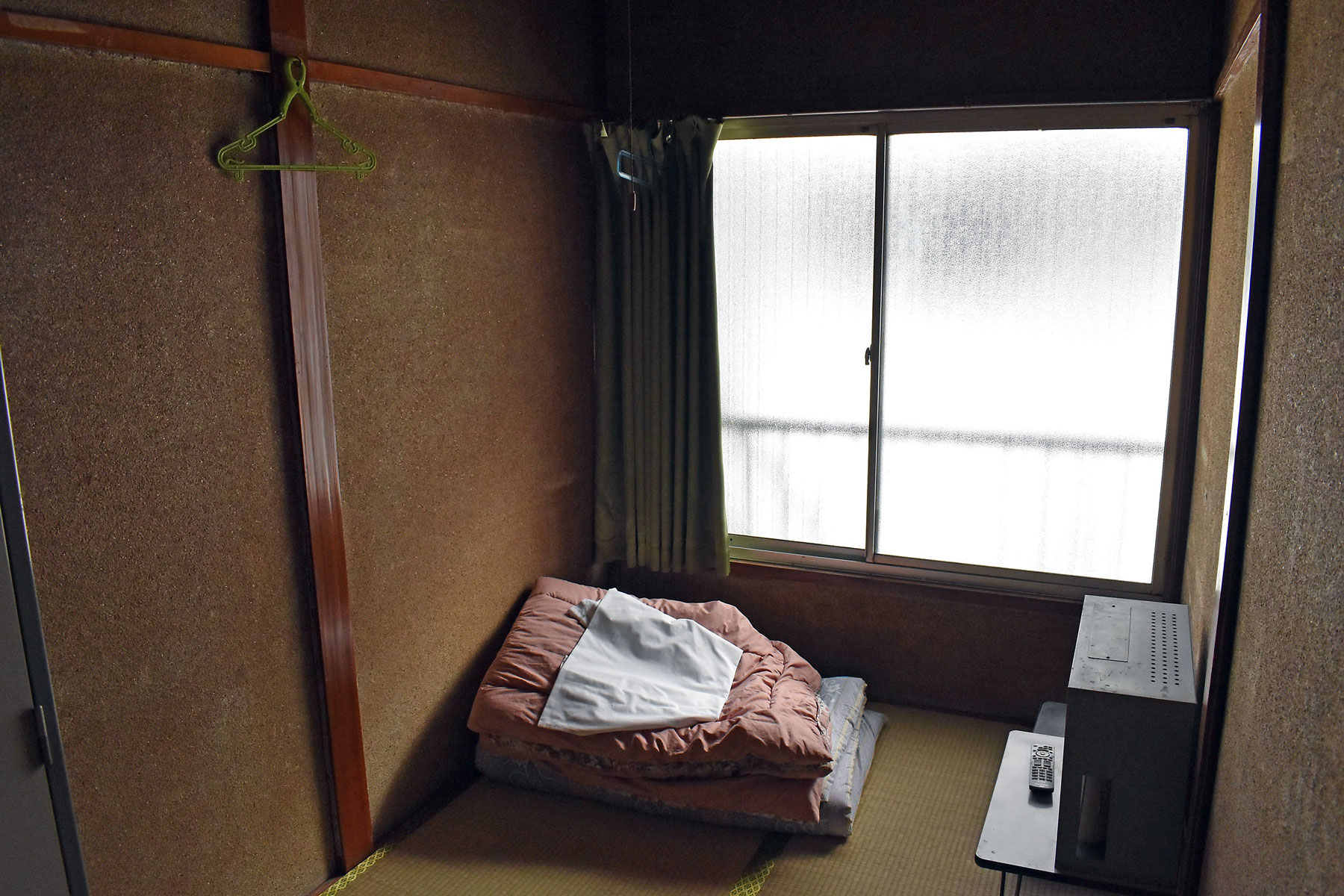

But the very kind of face-lift Miura sounds the alarm about is taking place in Nisshincho, a place synonymous with the flophouses that have for years provided day laborers and elderly welfare recipients with a semblance of a social safety net.

Due to the low rent and the lack of a need for guarantors, these cheap inns have not only served as convenient temporary dwellings for day workers without fixed addresses, but also played a vital part in accommodating them as welfare recipients once they are too old for manual labor. Some of these “retirees” would settle there, regarding the inns as something of their final abodes.

In what became a catalyst for change, however, the deadly fire that erupted in Nisshincho in May 2015 burned down two of these cheap inns, killing 11 lodgers trapped inside.

The fire is thought to have spread quickly in part because the inns illegally constructed additional floors to increase their capacity — at the expense of fire safety standards — an expansion that the city later found common among similar inns in the area.

This prompted authorities to crack down on the flophouses, resulting in the number of such dwellings being nearly halved from 49 in May 2015 to just 26 by last March, according to figures provided by the city. In September 2015, the city launched an initiative seeking to facilitate the transfer of welfare recipients living in these cheap inns to apartments.

Miura laments what he considers the city’s attempt to “crush” a symbol of blue-collar workers who underpinned Kawasaki in its toughest times.

“Is it really OK that the history of these inns is being done away with?” he asked.

But for Tomoko Saito, 51, the changing landscape of Nisshincho was a long time coming.

In March last year, Saito reopened her family’s inn under the new name of Kado Yado — a step she took after her mother, the previous owner, had hemorrhaged traditional patrons due to the city’s policy of directing welfare recipients away from flophouses.

Kado Yado’s debut was partly subsidized by the city as part of its “inbound business promotion” initiative. Today, what used to be a “dimly lit,” “dirty” inn — as Saito put it — catering almost exclusively to elderly men on welfare has gotten a new lease on life as a stylish guesthouse open to tourists and businesspeople, including women.

On the first floor are cozy single rooms available mostly for short-term guests at just over ¥3,000 per night. Although Kado Yado’s predecessor, Kawasaki Business Hotel, was rejecting female customers due to the lack of a restroom for women, it now has one, and counts among its clientele a sizable number of foreign tourists, including those from Taiwan, South Korea, Malaysia, India and Brazil.

“Although there was a time I felt the city was trying to drive us out of business, it is now cooperating with us to innovate in this town,” Saito said. “I think it’s a great move.”

This is not to say Kado Yado’s traditional customers are gone. Some still occupy the more humble three-tatami-mat rooms on the second floor.

“They have been with us for so long. Some of them actually think this is their home until death,” she said. “So I decided to aim to coexist with them.”

On a recent afternoon, one 69-year-old welfare recipient who gave only his last name, Asano, was milling about in a park in Nisshincho.

Asano, who spent most of his life making ends meet as a day laborer in the construction and shipbuilding industries, says he arrived at a Nisshincho flophouse about 10 years ago after surviving other doyagai in Japan, including Kotobukicho in Yokohama and Sanya in Tokyo. Like many others, he says he was asked by the city to relocate to a nearby apartment after the fire.

“Nisshincho is my terminal station,” Asano said with a wry smile on his face. The last 10 years, he said, have seen Nisshincho take on a new, more “peaceful” look, frequented by less boozers and by more tourists.

“I kind of liked it better the way it used to be, though,” he said, as if recalling fond memories from a bygone era.

“I can’t quite put my finger on it, but it was more … fun.”