THE CLIMATE CRISIS

Emergency on Japan’s ‘lucky island’

The sun sets over Iki Island's Gonoura Port. The Nagasaki island is the first place in Japan to declare a climate emergency. OSCAR BOYD

Nagasaki Prefecture’s Iki Island is the first place in Japan to declare a climate emergency. It now needs to lead the charge toward a more sustainable future

JESSE CHASE-LUBITZ and OSCAR BOYD

Staff writers

It’s golden hour on Iki, a pristine island in southwestern Japan. A gentle breeze cools the day to a perfect 24 degrees Celsius. The roads are clean, the trees are green, a playground sits atop a grassy hill. Locals call Iki a “lucky island” because it’s rarely affected by natural disasters.

And yet, last year Iki became the first place in Japan to declare a climate emergency.

On Sept. 25, Iki joined more than 1,250 jurisdictions in 25 countries in the emergency declaration. The goal of such an action is to mobilize resources “at sufficient scale and speed to protect civilization, economy, people, species and ecosystems,” according to the Climate Emergency Declaration website.

Although the island has made few headlines for destructive typhoons or flooding, Iki faces systemic and urgent threats. As a small, isolated city with a rapidly declining population, it embodies many of the problems faced by island communities across the country.

With just two Family Marts on the island, Iki stretches 17 kilometers from north to south and 14 kilometers east to west. In a car, it takes less than 40 minutes to cross. Many of its residential areas are concentrated around the coast, so the island is vulnerable to sea level rise, and its dependence on the fishing and farming industries makes the effects of the climate crisis an increasing concern.

Japan topped the list of countries most affected by the climate crisis in 2018, according to the latest Global Climate Risk Index report published by environmental think tank Germanwatch in December.

As the first locality in Japan to declare a climate emergency, Iki has taken on the responsibility to set an example for the impact of climate declarations nationwide.

Declaring an emergency

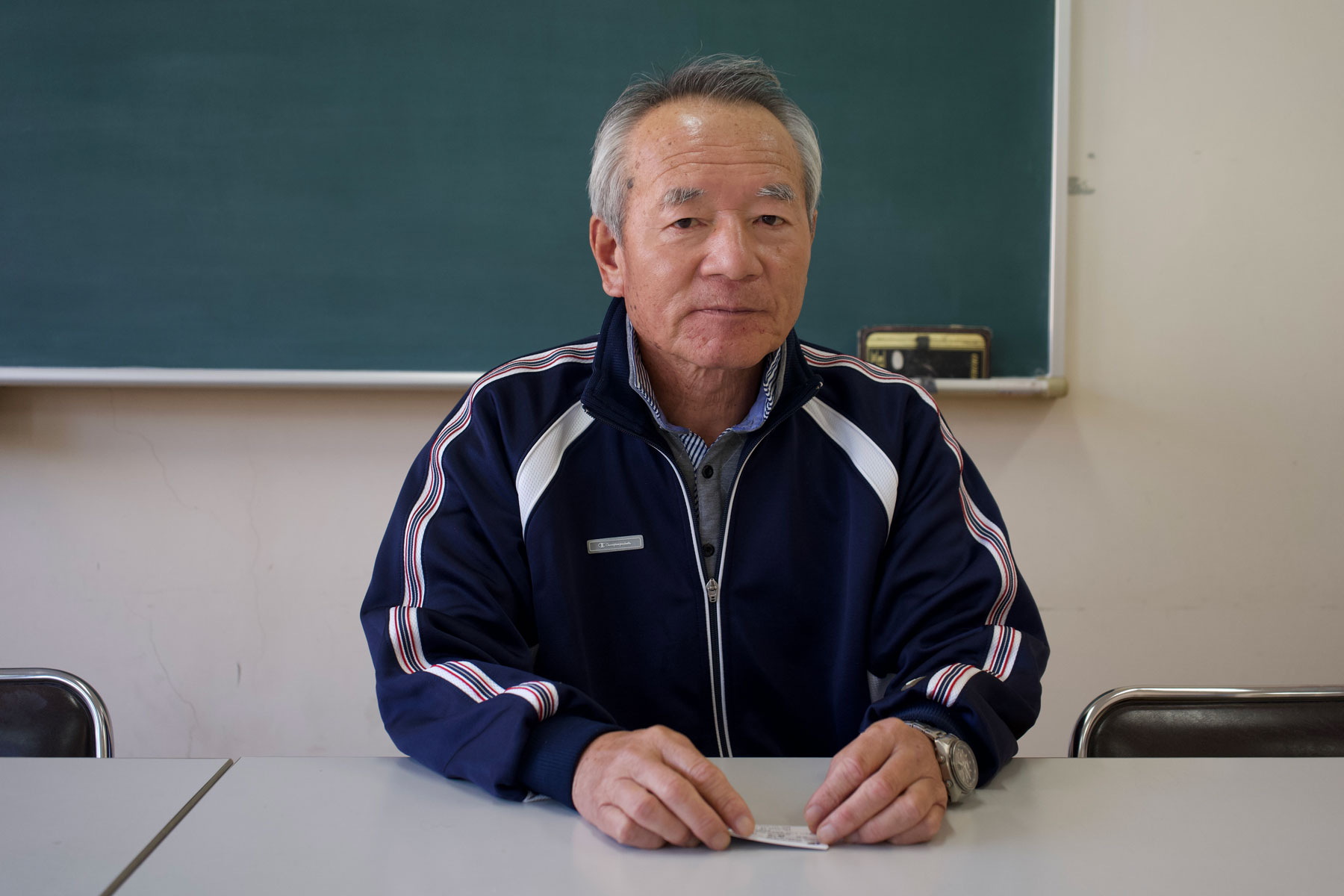

Iki Mayor Hirokazu Shirakawa, 69, is polished, happy and hopeful.

While he agrees that Iki is facing immediate problems, he focuses instead on the innovations the island hopes to test and implement in the future as a government-selected SDG (Sustainable Development Goals) Future City: using AI to cultivate asparagus and drones to carry agricultural goods, testing hydrogen engines for vehicles and connecting Iki to the power grid on mainland Kyushu.

When asked what he sees as the ideal outcome of the declaration, Shirakawa says he hopes to raise awareness about the environment among Iki’s residents.

This is one of the four main objectives of the island’s declaration and so far, where it has been most successful.

The other listed goals are replacing fossil fuels with renewables by 2050, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and contacting other government offices to take action.

The declaration has already alerted some islanders to the effects of the climate crisis. There are new educational initiatives that focus on raising environmental awareness in schools as well as events such as a garbage collection campaign in which 20 schools compete against each other to pick up the most trash within an hour.

“I was surprised when they declared,” says Akihiro Shimojo, 52, the owner of a fruit shop at the Katsumoto morning market on the eastern part of the island. He wears a bright red jacket, matching the vibrant colors of the fruit he sells.

Located at sea level a block away from the ocean, his shop gets flooded about once a year. But other than plastic waste on the beaches, he says he hadn’t really considered environmental threats before the declaration was publicized.

Shimojo sees it as the government’s responsibility to take the lead, after which individuals should take action.

“The government makes the opportunities, but people need to take responsibility to self-actualize,” he says.

Beyond spreading awareness, Iki’s emergency declaration promises to increase reliance on renewable energy and decrease greenhouse gases. The city is making less progress in these categories.

Located about 70 kilometers from Kyushu, Iki runs on its own power grid. Wind currently makes up 2 percent of the island’s energy mix, while solar makes up about 7 percent. Its potential is greater: The solar panels were shut down 70 times between 2016 and 2019 because the island doesn’t have enough batteries to store the energy they produce, and it is easier to turn off renewable sources than the diesel generators that produce much of the rest of the island’s energy.

The mayor is hoping to replace fossil fuels entirely with renewable energy sources by 2050, with intermediate goals of 24 percent renewable energy by 2030 and 15 percent by 2024. Little has been done to meet these objectives to date.

“Right now, solar power is seen more as a backup,” says Michihiro Shinozaki, a government official and part of Iki’s SDG team, as he looks out over the island’s largest solar field.

As for greenhouse gases, plans seem to run counter to expectations. Despite the fact that cattle farming is extremely carbon intensive, the city is planning on increasing its current head of cattle from 7,500 to 8,600. And to help improve transport connections to the island, Iki hopes to extend its airport runway, which will increase the number of planes that visit and, as a result, the amount of carbon released.

But in addition to the goals laid out in the declaration, Iki is just beginning to feel the effects of more urgent issues that all of Japan will have to face. While the emergency declaration is focused on the future, little attention is being paid to the present.

Seaweed deserts

Fishermen Yasushi Matsumoto, 51, and Katsuyuki Sakaguchi, 43, suit up every day to dive into the oceans surrounding Iki. The two of them grew up on the island and have been working for Katsumoto Fisheries for the majority of their lives. Twenty years ago, they were part of a team of 40 divers at the fishery. Just 10 divers remain today.

Both Matsumoto and Sakaguchi wear camouflage pants, but it seems to be more out of personal preference than part of a uniform. Sakaguchi sits down at a large oval table in a stark conference room at Katsumoto Fisheries and puts his shaved head into his hands. The emptiness of the room matches the tone of the conversation.

“We see half of what was there three to four years ago,” Sakaguchi says of a typical catch, with a resigned look in his eyes.

The main challenge to Iki’s fishing industry is the steady decline in local seaweed beds in recent years. Seaweed is essential to biodiversity, as it provides oxygen and absorbs carbon dioxide. The loss of these beds is so widespread in Japan that there is a word for it — “isoyake” (seaweed desertification).

The decline is primarily the result of rapidly rising sea temperatures, according to a study published by the Journal of Coastal Research in 2018. Over the past 100 years, sea temperatures around Iki have increased by an average of 1.24 degrees Celsius. The seaweed beds around the island were particularly affected in 2013, when sea temperatures rose to above 30 degrees Celsius for eight consecutive days, loosening the seaweed from the ocean floor and leaving it vulnerable to a subsequent typhoon that washed many of the beds onto the beaches.

Without seaweed, there is little to draw fish to Iki’s shores.

Katsumoto Fisheries purchased a big reel for catching tuna a few years ago using government subsidies, but it isn’t making much of a difference now. “Even if the government helps us buy new machines or technology, it’s meaningless if there aren’t any fish,” Matsumoto says.

Between 2008 and 2017, the annual catch declined from 8,560 tons to 4,408 tons — a decrease of approximately 50 percent. When asked what will happen if the catch continues to decline, Matsumoto says that the fisheries would close. “There wouldn’t really be anything left to do,” he says.

While the fishermen on the island have observed the decreasing fish population for years, they are struggling to find solutions. They have tried catching different fish such as grouper and sea bass as new species move north with the temperature rise, but no large-scale actions have been implemented to address the root of the problem.

“The impact on the fishery industry, which is a key industry, has become serious,” Iki’s 2019 climate plan acknowledges. As of now, however, there are no plans in place to address the issue.

Fishing is fundamentally important to Iki’s economy. In 2017, the fishing industry made ¥2.6 billion. In 2007 — 10 years earlier — it made double that. The decline is having a ripple effect on other industries as well.

Seiji Okamoto, 45, is wearing a pair of black overalls as he sits on a cushion on the floor of his home-turned-Airbnb. Pictures of five different cats are posted to the door to inform guests about which ones are allowed outside and which are not.

Okamoto was born and raised on Iki. Around 10 years ago, he took over his family business of restoring boats for the island’s dwindling number of fishermen.

Recently, customers have had a harder time paying him for his services. “Two or three years ago, fishermen always paid me quickly, but now they ask to wait,” he says. “It’s a problem for my company.”

His customers are also asking to pay in installments. “I understand it,” Okamoto says. “It’s impossible for fishermen because there are so few fish.”

When Okamoto steps away for a moment, his friend and business partner Tomoko Mori, 51, says, “If the problem continues and they can’t catch fish, he might not have any work.”

Okamoto is already trying to capitalize on the changes, however. He has started to reorient his business toward boat crushing services. As the number of fishermen decrease, unused boats are increasing. He is waiting on a license from the government to make this into an official business.

Both Okamoto and Mori are nervous, but they plan to stay on the island. “For now it’s OK,” Okamoto says, “but in 20 years, we might have to think about this again.”

Iki Island's vulnerability to rising sea levels and its dependence on the fishing and farming industries makes the effects of the climate crisis an increasing concern. OSCAR BOYD

Rain, rain, go away

Although Iki has historically avoided natural disasters, over the past three years, torrential rains have brought the island to a standstill on three separate occasions.

In 2017, the island was hit by a series of heavy rainfalls that kept people in their homes for days. The first was at the end of June, when it rained for 24 hours and recorded a peak hourly rainfall of 118.5 millimeters. The storm caused 19 landslides, eight flooded roads, two hours of power outages and 300 farmland-related disasters.

This level of rainfall was, until recently, considered to be a once-in-50-year event. But these storms have become more frequent; similar levels of rain were recorded once more in 2017 and again last year.

The flooding puts particular pressure on the agricultural industry, which employs around 1,700 people, or 13 percent of the island’s workforce. When heavy rains hit, farmers lose crops and shop owners lose money.

Hiromi Hirayama, 72, is the owner of Hirayama Ryokan in Yunomoto. Hirayama’s daughter-in-law, Makiko, 44, sets out a traditional Japanese breakfast: a raw egg, pickled vegetables, rice. The meal is made special with a sampler of fresh vegetables: bitter melons, cucumbers, sweet peppers and carrots.

“Eat the roots,” Hiromi says, pointing to the leftover stalks and leaves. “That’s where you will get the power.”

The Hirayamas grow their own vegetables and tend to 100 chickens and a horse on a farm nearby. In the heavy rains of 2017, they lost their entire crop.

Others were hit indirectly by the rains.

With every typhoon, fruit and vegetables become more expensive as his providers’ farms are flooded. For fruit seller Shimojo, produce becomes harder to sell.

In 2017, Masato Sutoh, 75, director-general of Ikikoku Museum, watched as a landslide swept away a temple just 400 meters from his house during the downpour.

Sutoh is an archetypal intellectual collector. Disheveled piles of papers and books are separated by artefacts and small artistic knick-knacks on his desk. An abstract piece of art hangs on one wall and bookcases line the other. His hands clutch the side of the chair he’s sitting on as he talks.

“It took nine months to repair,” he says.

Sutoh believes that Japan’s approach to the climate crisis is dependent on the action Iki takes.

“It’s important to actually do something in order to set a precedent,” he says.

Beyond the island

Iki’s climate declaration also aims to encourage other parts of Japan to take similar action. It’s an approach that seems to be working.

Since Iki declared, other cities have reached out to the mayor’s office for guidance, according to Iki officials. The city of Kamakura in Kanagawa Prefecture drafted its own “demand,” although the city council there has yet to make it official.

“After having made the climate emergency declaration, we are looking at other municipalities across Japan, including Iki City … as we create our plan to address climate change,” the Kamakura local government told The Japan Times by email.

In mid-December, Nagano became the first prefecture in Japan to declare a climate emergency.

“Iki City is grateful that the climate emergency declaration movement has been spreading,” the island’s local government said of the actions by Kamakura and Nagano. “We hope more and more prefectural governments and city governments in Japan declare climate emergencies from now on.”

Environmental groups are calling on more local governments to do the same.

These groups feel that climate emergency declarations can be particularly impactful in Japan, where many people aren’t aware of the environmental crisis due to a lack of access to English media and reporting in Japanese.

Student climate group Fridays for Future Tokyo has successfully petitioned the Metropolitan Government to declare; late last month, the municipality published its Zero Emission Tokyo Strategy, which recognized that it is “currently facing a climate crisis.”

“A declaration by the governor of Tokyo will open up people’s eyes and change would come after that,” said Isao Sakai, 18, a member of Fridays for Future, before the declaration was made. “First people need to wake up to take that action.”

Sakai says that most people are ignorant about the state of the climate and he thinks the declaration will publicize the problem to the Japanese people.

“If Japan did declare a climate emergency, hopefully the nation will realize that we are facing a crisis,” says Yoshiko Ichikawa, 30, an organizer with environmental group Extinction Rebellion Tokyo. “No one is talking about it right now.”

And, for now, the national government doesn’t plan to either.

“We recognize there are (declarations) in other countries, but we have no plans to make an emergency declaration at a government level,” says Takeo Sugii, an official at the Environment Ministry.

The government sees value in making emergency declarations at a local level to spread the word.

“The emergency declaration is aimed at raising the awareness of residents and is part of a larger trend to address climate change,” Sugii says.

‘Finding a way out’

Despite the fact that Iki’s declaration comes with an increasing body of evidence showing Japan’s vulnerability to the climate crisis, it’s unclear whether the declaration will spark enough action to make a difference.

From the perspective of the local government on Iki, the emergency declaration is meant to spread the word and encourage action among individuals.

Tatsuo Tsuji, 69, a disaster volunteer who has spent 50 years on Iki, says “the climate declaration is like yelling ‘fire’ in a movie theater — it shocks everyone into finding a way out.”

However, many believe a declaration alone is not enough.

“(Declaring a climate emergency) can be a type of ‘greenwashing,’ you know, ‘Our city declared this — ta-dah!’ — and then nothing happens,’” says Hinako Arao, a field organizer at environmental group 350.org Japan. “Declaring a climate emergency always needs to come with that kind of action and commitment.”

Japan is now at a juncture. These declarations could inspire people to embrace sustainable lifestyles and force the government to commit to change. However, they could also relieve cities and prefectures of the responsibility to take further action.

Yelling “fire” in a movie theater certainly sparks urgency but, as evident in Iki’s struggle to address the climate crisis effectively, it doesn’t necessarily help anyone to find a way out.

The full climate crisis series:

- Part 2: Throwaway society: Rejecting a life consumed by plastic

- Part 3: Balance of power: Redefining Japan’s energy needs

- Part 4: Japan 2030: Tackling climate issues is key to the next decade

The Japan Times offset the carbon emissions produced while traveling for this story through donations.