HISTORY

State guesthouse

A peek behind the doors of Akasaka Palace

Akasaka Palace’s neo-Baroque Western-style exterior MARTIN HOLTKAMP

Having narrowly survived the Tokyo air raids in 1945, the State Guesthouse now welcomes visitors with open arms

MASAMI ITO

Contributing writer

Standing on the grounds of the State Guesthouse, Akasaka Palace on a crisp autumn day in November, it’s hard to believe you’re in central Tokyo, just a few minutes’ walk from bustling Yotsuya Station. Birds can be heard chirping in the nearby garden and, aside from catching the occasional word or two from other visitors engaged in conversation in the distance, the overall atmosphere is tranquil.

It’s just the ambience you might hope to find at a guesthouse, let alone a residency that used to belong to the imperial family and the added bonus of historical significance. The guesthouse has come a long way, however. Its role in society has changed over time. It has hosted a number of prominent global figures, including Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II, and continues to help anchor Japan’s diplomatic efforts at home. Ten years ago — on Dec. 8, 2009 — the palace was designated a National Treasure, virtually cementing its standing as an asset for future generations.

Most recently, the palace has served as the venue for dozens of meetings between Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and foreign dignitaries that included Chinese Vice President Wang Qishan and Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi. Abe met with dignitaries from about 50 countries in the space of just five days.

According to Masachika Kusaka, director-general of the state guesthouses in Akasaka and Kyoto, Abe broke the record for the number of summit meetings held at the palace in a single day, holding 23 one-on-one talks with foreign leaders.

“It was like a whirlwind,” Kusaka says. “We welcomed one dignitary after another and saw off one dignitary after another. We had to be careful to adjust the timing of each meeting so that none of the guests accidentally bumped into each other. Aside from the Prime Minister’s Office, there is no other place in Japan that can host such meetings insofar as capacity and quality are concerned.”

Red-carpet treatment: Guests enter the Akasaka Palace via stairs that lead to a hall on the second floor. MARTIN HOLTKAMP

Iron foundation

Constructed 110 years ago, the State Guesthouse was originally built as a palace for Crown Prince Yoshihito, who later became Emperor Taisho (1912-26). The two-story building stands in the middle of a 120,000-square-meter plot of land in central Tokyo, an area that’s roughly 2½ times the size of Tokyo Dome.

Under the direction of architect Tokuma Katayama, construction of the palace took about 10 years. Katayama is also famous for designing the national museums in Nara and Kyoto. He was one of the first students to study under British architect Josiah Conder at the Imperial College of Engineering, which is now known as the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Tokyo. Katayama was in the same class as Kingo Tatsuno, who was the architect behind the Bank of Japan and Tokyo Station buildings.

Many of the materials used to construct the palace had to be imported from overseas, including 2,800 tons of iron that formed the bedrock of the building’s foundations. In the early 1900s, Japan lacked the technology to construct buildings with iron and so Katayama was forced to import the material from Carnegie Steel Co. in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, as well as bring over a couple of technicians to assist in the project.

Comprised of iron weighing thousands of tons and an estimated 13 million bricks, the palace has survived several key moments in history, including the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake that devastated Tokyo. A third of the building is made of walls and pillars, with the walls’ thickness ranging from 56 centimeters to 1.8 meters.

“The palace didn’t move an inch during the Great Kanto Earthquake,” Kusaka says. “Japan didn’t have reinforced concrete in those days and, instead, the building was constructed in terms of utilizing what was the best earthquake-proof technology at the time. This is why it continues to remain standing today.”

The palace also survived the Tokyo air raids in 1945. It did, however, have a close call.

According to Masaji Yamato, an employee at the palace for more than four decades, two or three incendiary bombs struck the palace during one of the raids, tearing through the roof and landing on the second floor. Fortunately, however, the bombs never exploded and several hundred employees of the Imperial Household Agency dutifully wrapped blankets around the explosives before carrying them carefully outside, risking their lives to protect the palace from being destroyed.

“Without the efforts of those employees, the palace would have surely caught on fire and would not exist today,” Yamato says.

Restoration work

After World War II, ownership of the palace was transferred from the imperial family to the government.

For a short period of time, the palace was used in several administrative roles, acting as the National Diet Library, the Judge Impeachment Court and the Research Commission on the Constitution. At one point, it even served as the office for the 1964 Tokyo Olympic organizing committee.

In the late 1960s, the government decided to use the palace as a state guesthouse for visiting dignitaries.

With so much foot traffic having gone through the palace in the preceding two decades, however, the interior had deteriorated badly and the building needed substantial renovation. Like many places in Japan at this time, smoking was commonplace and years of exposure to cigarette smoke had damaged artwork on the walls and ceilings.

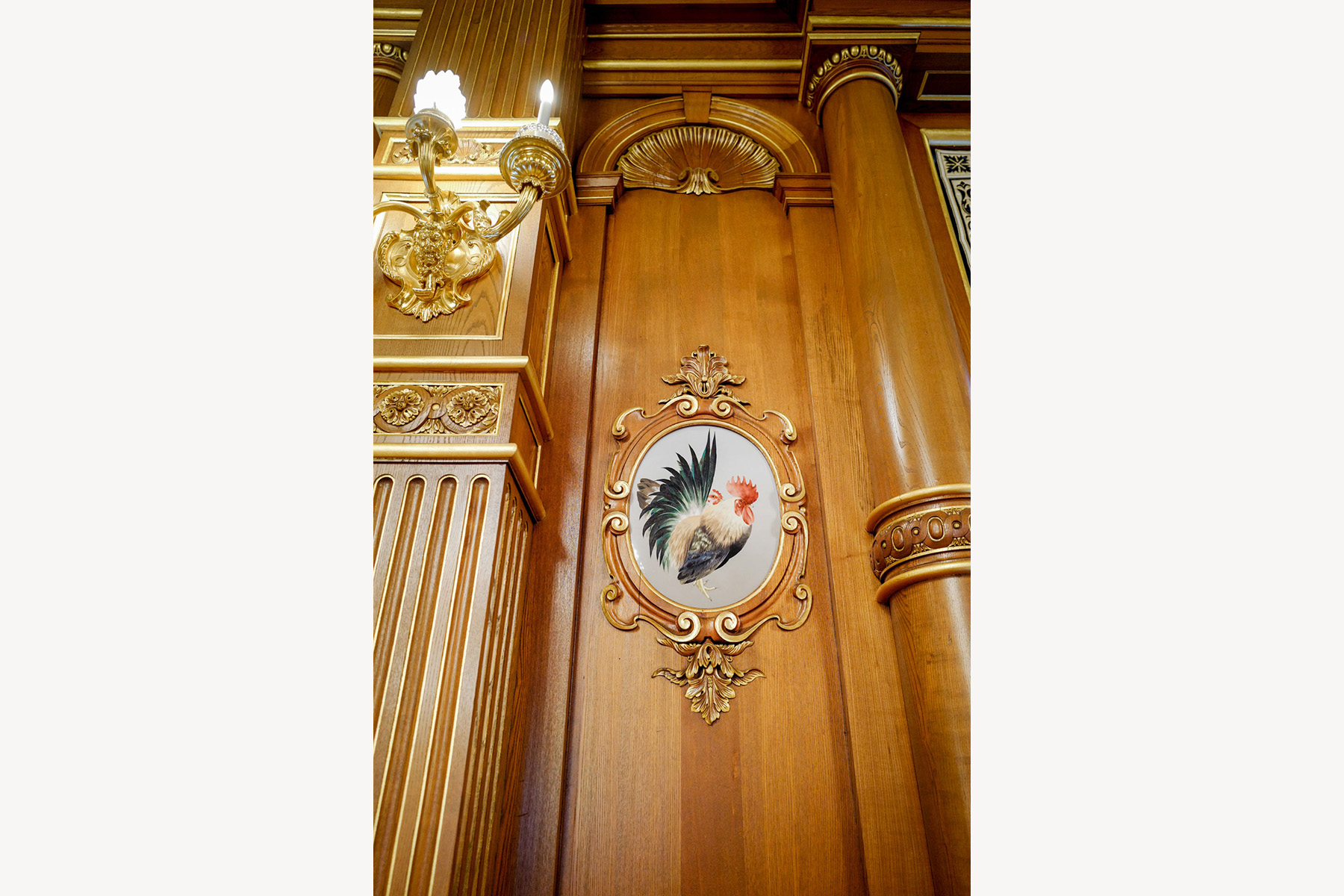

In one room that is called Kacho no Ma (Hall of Flowers and Birds), for example, which was once used as the National Diet Library’s reading room, smoke had ruined a Gobelins tapestry that had been hanging on a wall. Instead of asking Gobelins Manufactory in Paris to remake the tapestry, a domestic company was tasked with the restoration work.

Yamato says weavers re-created the tapestry by hand, using their own fingernails that had been deliberately sharpened for the task. However, the weavers were only able to finish about 2 centimeters a day, meaning that the entire process took more than three years. “Most tapestries these days are machine woven, so it’s extremely rare to see the hand-woven style you can see here,” Yamato says.

Six years after restoration work began, the palace reopened in 1974, welcoming then-U.S. President Gerald Ford as its first official state guest. Other prominent guests have included former Russian President Mikhail Gorbachev, former U.S. President Ronald Reagan, former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and former South African President Nelson Mandela.

A Japanese-style annex to the palace called Yushintei (Pavilion of the Buoyant Mind) was also unveiled the same year. Unlike the neo-Baroque Western style of the main building, Yushintei featured a number of traditional Japanese design elements, from its courtyard garden that includes stone from Kyoto to its spacious 77-square-meter tatami room.

The annex was built to host cultural events such as traditional dinners, lunches and tea ceremonies. No official meetings are conducted there.

The building found itself at the center of international attention in 2017 when U.S. President Donald Trump joined Abe to feed carp in a nearby pond. News outlets captured Trump pouring the fish food from a wooden box in one go, with media describing him as being culturally insensitive.

Yamato, however, scoffed at such reports, saying they were misleading.

“President Trump was using a spoon at first but the two leaders ran out of time,” he recalls. “First, Prime Minister Abe poured the rest of his fish food into the pond and President Trump just followed suit. That’s why he was mad — the media were only commenting on a single snapshot of the incident.”

Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko sat in these chairs when bidding guests goodbye in Sunrise Hall. MARTIN HOLTKAMP

Public access

While the Akasaka Palace was long the sole state guesthouse in Japan, the government decided to construct another facility in Kyoto. After the government gave its approval to the plan in 1994, the Kyoto State Guesthouse finally opened in 2005.

Employees at both palaces include officials from various government ministries and agencies based on expertise. A guesthouse’s architecture, for example, is overseen by staff from the Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry, while its garden is managed by employees from the Forestry Agency.

Yamato, meanwhile, oversees electricity and his teams patrol the grounds frequently to ensure that there are no wiring irregularities in an effort to prevent fires.

“Despite having many staff, taking care of the palace is certainly not easy,” Yamato says. “It’s precisely because people with experience in a wide variety of areas are here looking after the palace and its grounds that we are able to maintain it.”

After the fire at the Notre Dame Cathedral in April, Kusaka says the building has undergone a comprehensive check-up by the Tokyo Fire Department to ensure there are no potential hazards.

For more than 100 years, the palace was only open to visitors in a limited capacity. In 2016, however, it opened its doors to the public and now welcomes visitors about 250 days a year. When the palace is hosting guests, it is usually closed a few days before and after the visit.

The palace currently welcomes more than 500,000 visitors annually. Open through the week except Wednesdays — when palace staff spend the day on maintenance — there is an area in the garden where visitors can enjoy an afternoon tea set that includes pastries and sandwiches. From next spring, a cafe will open adjacent to the palace, just outside the main gate.

On special occasions, such as Christmas, the palace opens in the evenings, and visitors can enjoy illuminations over a glass of wine.

“There is no place like Akasaka Palace,” Kusaka says. “We want to share its beauty with the people of Japan as well as overseas visitors. I believe it’s my mission to ensure the palace is maintained and to safeguard it for the future.”

For more information on the Akasaka Palace, visit www.geihinkan.go.jp/en/akasaka.

Masachika Kusaka, director-general of the state guesthouses in Akasaka and Kyoto. MARTIN HOLTKAMP

The palace didn’t move an inch during the Great Kanto Earthquake. Japan didn’t have reinforced concrete in those days and, instead, the building was constructed in terms of utilizing what was the best earthquake-proof technology at the time. This is why it continues to remain standing today.”

Carp swim in a pond outside the Akasaka Palace’s Japanese-style annex. MARTIN HOLTKAMP