CULTURE

Under the big topof Japan’s Kinoshita Circus

Performers defy digital age to stay relevant more than 100 years since founding

ANDREW McKIRDY

Staff writer

Michael Howes claims his job is “no more dangerous than driving a car.”

“If you make a mistake driving a car, is it going to be a slight accident or a life-changing accident?” asks the 49-year-old Englishman. “It all comes down to the mistakes you make.”

Just five minutes earlier, Howes was shut in a cage with eight fully grown lions. At various points during his 20-minute performance, he coaxed the beasts onto pedestals and balance beams, commanded them to jump over each other and bent down to hug and stroke them.

Just another day’s work for a performer at Japan’s oldest circus company, Kinoshita Circus.

“This is my life,” says animal trainer Howes after a recent show near Urawa Misono Station in Saitama Prefecture, where Kinoshita Circus is performing twice a day until Sept. 23.

“Everyone at this circus has worked to be here, and every day works to stay here and make the circus great,” he says. “Everything we do is for this circus.”

Kinoshita Circus, which was founded in 1902, performs in four or five locations around Japan each year, setting up its bright red, 18-meter-high big top in each place for roughly three months. The troupe began this year in Osaka before moving to Nagoya and then Saitama, and will go on to perform in Takamatsu, Kagawa Prefecture, and in Fukuoka before the year is out.

Clowns entertain the crowd at a Kinoshita Circus show earlier this month in Saitama Prefecture. RYUSEI TAKAHASHI

The big top seats around 2,000 people, and the company says it attracts over 1 million customers a year.

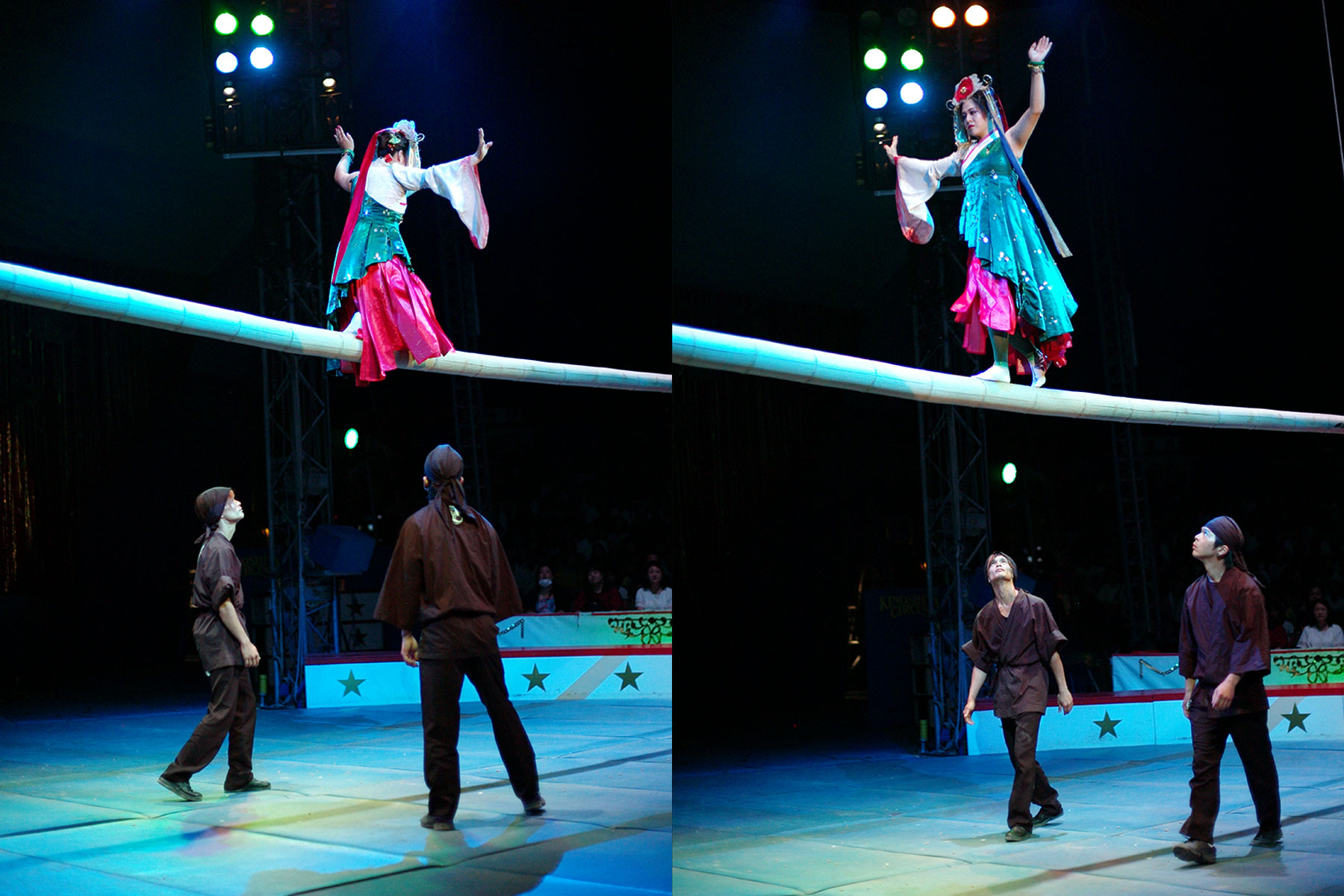

Each show lasts around 2 hours and 10 minutes with an interval, and features the full gamut of circus acts, including clowns, jugglers, acrobats, trapeze artists, animal trainers, illusionists and death-defying motorcycle riders.

Kinoshita Circus has around 50 to 60 performers, and around 20 are from overseas. Company President Tadashi Kinoshita says he scours the globe to find the best talent, assessing graduates from circus schools and regularly attending the annual International Circus Festival in Monte Carlo.

“A performer has to be able to move the audience,” he says. “To make them think something is amazing. That could be performing at a great height or making a funny joke on the ground. It could be performing on a trapeze or training wild animals. We bring together the best performers from each circus discipline.”

Training is essential for circus performers, who must hone their craft before they can appear in a show.

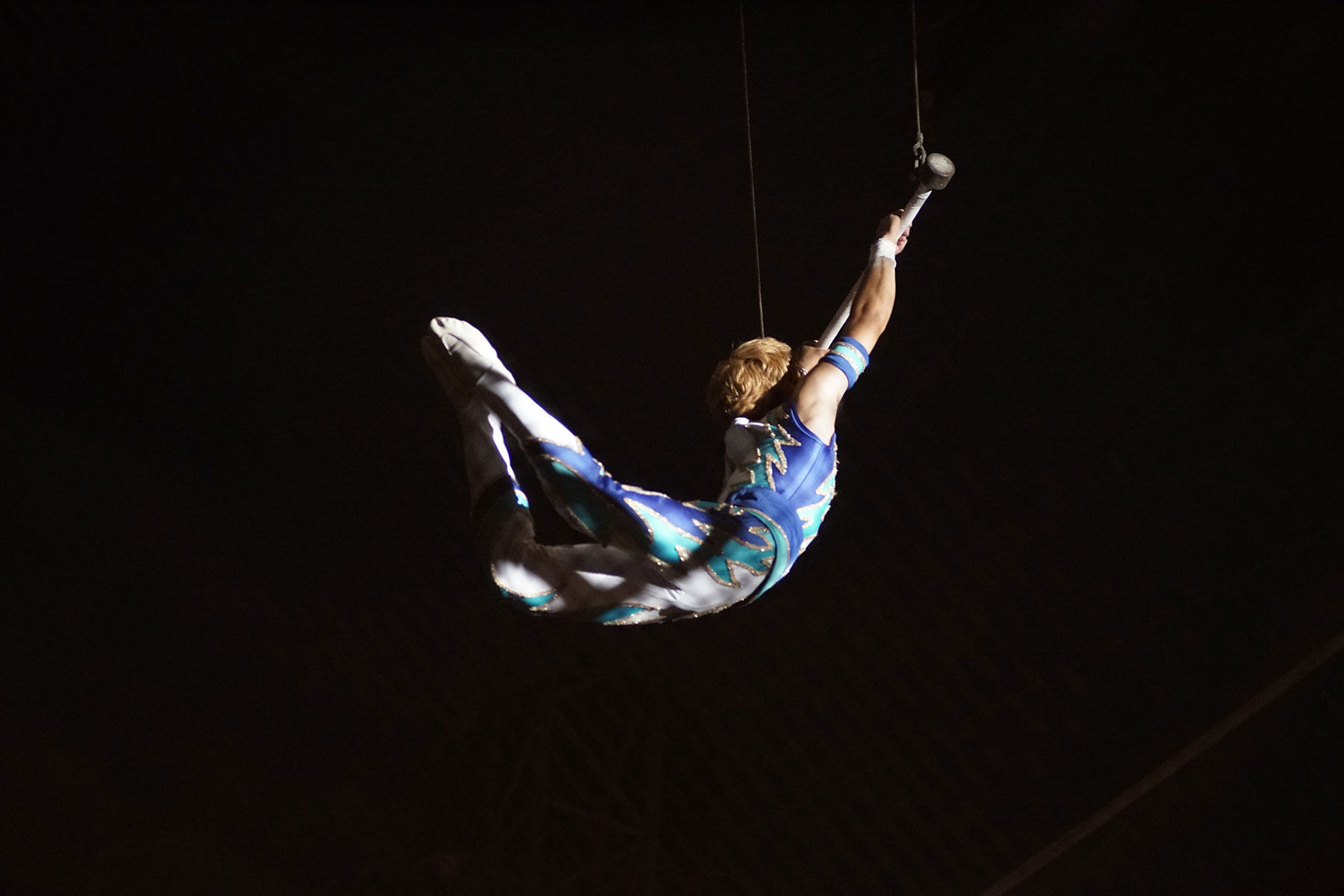

Yuri Hirata is a trapeze artist who joined Kinoshita Circus straight from university. She was a member of her school’s gymnastics club before joining the cheerleading team at university, and it was during that time she went to watch a performance by Russia’s Bolshoi Circus in Osaka. Inspired, she decided to apply for a position at Kinoshita Circus when a recruitment officer visited her university, and she was delighted to learn she had been accepted.

After a year of practice, she was allowed to make her trapeze debut in the show. Now, every day she soars through the air at a height of 13 meters, relying on her partners to catch her as she flies from trapeze to trapeze.

“It was scary at first,” says Hirata, who is now in her third year as a trapeze artist. “I started by practicing on a smaller trapeze, then once I had mastered the basics to some degree, I started doing it at the full height.

“I have made mistakes, times where I haven’t been able to reach the trapeze and have fallen,” she says. “The catcher catches me with both hands, but one time I couldn’t reach and I ended up being caught with just one hand. The trapeze wobbles a lot, and it’s at its fastest when it’s going forward. That was when I was only being held by one hand, and I thought I was going to die. But the catcher was a veteran and he reached out and grabbed me with the other hand.”

A safety net, of course, protects trapeze artists from the most serious danger, but not all circus performers have that luxury.

Animal trainer Howes was born and bred in the circus — he was even christened in a circus tent — and both his father and grandfather were animal trainers. When his father was killed in 1978 after a lion bit him in the neck during practice, however, his family tried to keep him away from animals until he was ready to decide his own future.

Howes says his father “made a mistake and paid the price,” but his death did not discourage him from following in his footsteps. After a 25-year career as an animal trainer for film and television, Howes decided to go back to his roots and joined Kinoshita Circus seven years ago.

“I took my kids out of school and my wife out of a job to come here, because this is my life,” he says. “You are either part of my life or you can stay at home.

“It’s very strange for people to see this life we have here, but unless you’re in it, it’s very hard to understand.”

Howes also performs with zebras, but his lion act is undoubtedly one of the show’s main attractions. He describes his eight lions — four brown and four white, six females and two males — as “my whole world,” but that doesn’t mean he can let his guard down for even a second.

“The lions are very well trained but they’re individuals,” he says. “My lions are not the same as any other person’s lions. Each animal is unique in itself. Each one is different, and can be different each show. I have to be on the ball to see the differences.

“Sometimes I have to use my voice to be a bit stronger,” he says. “Sometimes a bit less, because of the way they’re reacting. From start to finish, I feel what they’re feeling. And they feel what I’m feeling. It comes with experience.”

In 1980 Japan ratified the Washington Convention, a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals that came into effect in 1975. The Washington Convention prohibited circuses from importing and exporting certain species of animals, and placed restrictions on animals they could buy from zoos.

Kinoshita Circus features zebras, lions and elephants in its show. The Washington Convention prohibits trade in elephants, but Kinoshita Circus has a friendship arrangement with the government of Thailand that allows it to borrow the animals for short periods. The circus donates a portion of its profits to elephant conservation efforts, which has helped to establish an elephant hospital in Thailand.

Kinoshita Circus features elephants, lions and zebras in its shows. RYUSEI TAKAHASHI

Many people around the world are opposed to circuses with animal acts on moral grounds, and several countries have implemented total bans. Howes concedes that he can’t change people’s opinions, but he is at least steadfast in his belief that his animals are well looked after.

“We believe in animal welfare,” he says. “Welfare is proven scientific facts about what animals need or don’t need, the stresses that animals feel. There have been many studies done that proved that animals in circuses are not cruelly treated and do not suffer in that environment. They actually thrive in that environment.

“I know what my animals need, and that is to be looked after every single day and be given what they need,” he says.

Attitudes toward animals in circuses have evolved over the past century, but Kinoshita Circus has seen many other changes in society since it was founded almost 120 years ago. With so many forms of entertainment available to consumers in the digital age, how does the circus manage to stay relevant?

After location and publicity, it all comes down to the show, Kinoshita says.

“It’s a question of quality,” he says. “If the show is good, people will come. And if it’s not, they won’t.”

Kinoshita, a graduate of Meiji University, turned down a job offer from a bank to join the family circus as a trapeze artist in 1974. He broke his neck in an accident shortly afterward and was hospitalized for three years, but he eventually recovered and went on to succeed his elder brother as president in 1991.

In 2015, Kinoshita was awarded the honor of Ambassador of Circus by the World Circus Federation, and he has also served as a judge at the International Circus Festival, which he describes as “the circus Olympics.”

After almost 50 years of being involved in the circus, he remains just as spellbound as the day he joined.

“About 10 years ago, I went to the circus festival in Monte Carlo and there was a Russian girl there, about 18 years old,” he says. “She was trying to do a triple somersault on a beam. She managed to do it, so the next time she tried to do four rotations. She failed the first time, and again the second time. She tried again and failed again, but the crowd of 5,000 people gave her a standing ovation because they were so moved by her courage in trying. When I saw that, I thought that was the beauty of the circus — the bravery of people trying.”

Family keeps business afloat in good times and bad, in war and peace

Circuses have a long history in Japan, with early street entertainment troupes known as kyokubadan flourishing during the Edo Period (1603-1868).

The arrival of American acrobat Richard Risley Carlisle in 1864 introduced the modern circus to Japan, and by the early 1900s there were over 30 troupes traveling throughout the country.

Tadasuke Kinoshita founded Kinoshita Circus in Dalian, China, in 1902, and returned to Japan two years later after the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War. The circus, featuring acrobats, horse riders, bears and elephants, became a big hit and continued performing during World War II, using only female performers as all the men had been called up to fight.

When a fire broke out at Izumo Taisha shrine in Shimane Prefecture in May 1953, a member of the circus helped put it out and was rewarded by the National Commission for the Protection of Cultural Properties.

Son-in-law Mitsuzo Kinoshita took over as its second president in 1959 and proceeded to take the troupe to other parts of Asia and the Pacific for a series of performances.

Mitsuzo Kinoshita’s eldest son, Mitsunori, then became president in 1983. After he died in 1991, Mitsuzo Kinoshita’s youngest son, Tadashi, was promoted to the top position.

“I had to try to turn the company around because we had debts of around ¥1 billion when I took over,” Tadashi Kinoshita said. “We repaid that in about 10 years.”