CULTURE

Reborn-Art Festival: ‘Texture of Life’

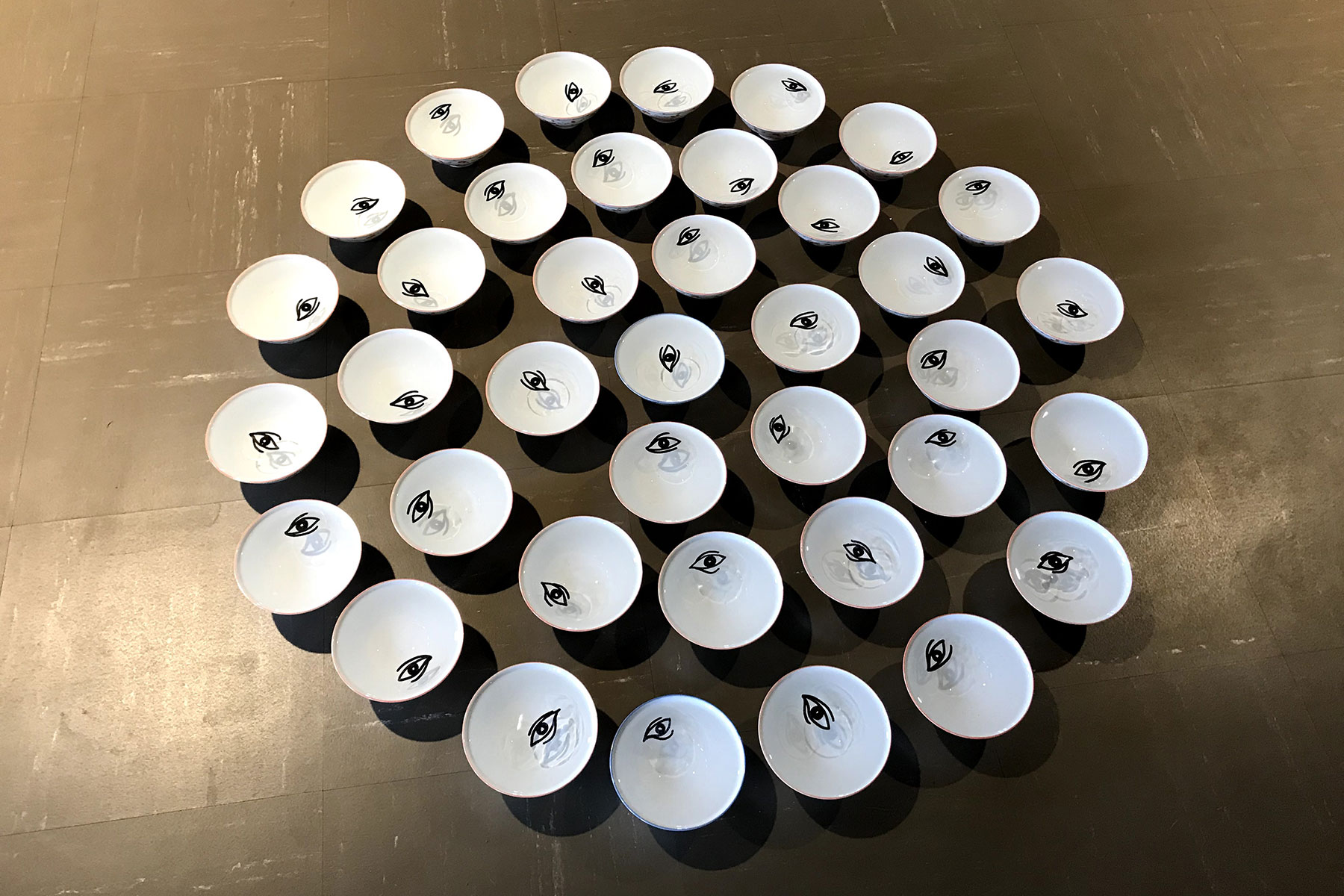

A Tohoku community gets a new lease of lifeAn installation by Yayoi Kusama at the Reborn-Art Festival YUKIHIDE NAKANO

Can curated works of art help a Tohoku community affected by the 2011 disaster to heal?

JOHN L. TRAN

Contributing writer

Climbing the stairs of Ishinomaki’s first department store, built in 1930, I can hear the sound of a man singing and the gentle strumming of an acoustic guitar. The voice is not one of a professional crooner; it’s raspy and unsure, and sounds like an amateur retelling a tale of sorrow without too much regard for being melodious or soothing. Arriving at the second floor, I can see hundreds of rice bowls filled with water and arranged into circles. A picture of an eye floats in each one.

In the course of telling the audience about himself and his work, the performer says, “I’m a shaman; I don’t want to be an artist, I want to be nothing” as well as “the most important thing to being human is heart.”

The performer is dressed as if he’s a local hippie who has popped in from a lazy — and maybe fruitless — day of fishing.

However, Zai Kuning is not a local. Kuning represented his native Singapore at the Venice Biennale in 2017 with a huge boat that was a product of his ongoing interest with the seafaring Orang laut ethnic group, but it can be said that much about his work is representative of some of the underlying themes and concerns of the Tohoku-based Reborn-Art Festival, which opened on Aug. 3 and runs through Sept. 29.

Microcosm and macrocosm, the relationship of the individual and the collective, and between humans and nature, art as being distinct from or a part of everyday life, and art as a form of spiritual palliative — these topics often appear in the background of contemporary art in Japan.

The Reborn-Art Festival is no exception, and because the event exists as a response to the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami of 2011 and takes place in and around Ishinomaki, Miyagi Prefecture, there is particular poignancy to how these matters are pursued.

This year’s Reborn-Art Festival, organized by musician and producer Takeshi Kobayashi, has seven different areas that have been curated independently of each other, with the overarching theme of the festival described as “Inochi no Tezawari,” which has officially been translated into English as “Texture of Life.”

Kuning’s work appears in an area curated by professor Shinichi Nakazawa, whose research interest is “spiritual archaeology” (a field of his own creation), which could be characterized as exploring the role of intuition, social rituals and nonrational thinking in making us human.

Kuning and Nakazawa seem to have a shared interest in life untamed by rationality (Nakazawa heads the Institut pour Science Sauvage at Meiji University) but, if you’re after rambunctiousness, the adjacent “Manga Road and Art Road of the City” that has been curated by Ishinomaki-based artist Kaoru Arima will not disappoint.

Arima’s work in the festival includes a series of beautifully executed — but also fantastically perverse — color sketches called “Art Dracula” that are reminiscent of ghost and demon woodblock prints of the Edo Period (1603-1868) as well as the outsider art of Henry Darger. They appear in an old flower shop renamed the Art Drug Center; Arima says that when he named the building, he was thinking of art as a cure rather than substances of the “Breaking Bad” variety.

Takefumi Shibuya, a young artist from Yamagata Prefecture, has created a hot mess of scaffolding, ready-mades, video, photography, kitsch paintings and plaster-cast dogs in another unused shop space. Much of the imagery comes from Shibuya’s strong interest in judo, and the incongruity of this topic in art and the obsessive way it repeatedly appears makes his work strangely intriguing. It may be full of personal references without which it is not fully comprehensible but its attraction is that seems both chaotic and highly organized at the same time.

Toshinao Aoki has created a classroom space in a high-street building and filled it with oversize prints of high school girls drawn in manga style. The characters are cute and sweet, of course, and they are totally absorbed in their own worlds. The initial impression is one of fun and lightheartedness, however, because the characters do not appear in connected sequences, and are surrounded by a thick black border, it’s also possible to see them as trapped in a moment of their story, without the possibility of being able to move back or forward.

The Kozumi site, curated by Hideki Toyoshima, is about an hour by car from Ishinomaki, and is in a forest clearing surrounded on three sides by hills. In an interesting defiance of making the place look like it is in harmony with nature, the artists’ work is housed in the confinements of prefabs, which seem miserably small and ugly in the expanse of greenery that has nominally been made available. The point is that prefab housing has been an inescapable sight wherever construction work has taken place after the earthquake and tsunami, and Toyoshima has decided not to disguise his use of them. Inside the prefab huts are environments that are closer to traditional gallery spaces than most of the other venues used in the festival.

In reference to the deer hunting and butchering of the Oshika Peninsula, the idea behind Toyoshima’s curation is to imagine ourselves as deer, and consider what insights that might bring.

Daizaburo Sakamoto, who lives as a mountain ascetic in the Yamabushi tradition, and contemporary dancer Yuko Okubo have recorded the enactment of a ritualistic performance and set this up in one of the darkened prefabs as a three-screen video installation. Fresh tree branches have been used to decorate the walls.

Yusuke Arai has painted the interior of his prefab with imagery that in coloring and style resemble Australian aboriginal art. On this background, Arai has also pasted some beautiful illustrations painted onto photographs.

Nao Tsuda is showing a previously published photo and poetry project that features images of a Lithuanian summer solstice ritual, along with new photography of the deer culture in the local area.

Yumiko Horiba uses animal bones, skulls and fur to create surreal, disturbing objects that are nevertheless visually seductive.

Breaking out from the confines of the prefab and also perhaps exploring something else than reverence of folk tradition as an opposition to technological modernity, Lieko Shiga’s work is a mass of oyster shells that spill down from the hillside into the forest clearing. It barely looks like it’s artificially arranged, and while it references the shell mounds of the Jomon Period (10,000 to 200 B.C.), the title “Post Humanism Stress Disorder” implies that it is looking forward in time, rather than back. Is it a forewarning that a breakdown in civil society and return to nature might not be as great as many of the other artists seem to suggest?

Etsuko and Koichi Watari’s curation on the island of Ajishima is about moving on after the 2011 disaster. The island is the furthest festival site from Ishinomaki and was not as drastically affected by the earthquake or tsunami as the coast of the mainland. The brother-and-sister team curated part of the first Reborn-Art Festival in 2017 and found the experience too distressing to work again in an area hit with so much tragedy, hence the move to the Ajishima and the theme of “Next Utopia.”

The individual works do not explore the idea of utopia in the sense of suggesting organizing principles for a perfect society but rather, collectively, they express something of the artists' hope for some kind of progress. The Wataris do not even agree between them as to what utopia is. Koichi says he is interested in the slower pace of rural life. For Etsuko, it’s about a positive and creative state of mind, rather than a place.

Some of the most technically impressive work of the festival can be seen on Ajishima, including the extraordinary audio-visual installation “Dissonant Imaginary” by Daito Manabe and Kamitani Lab.

Installed in a traditional storehouse, a projection of colored shapes pulse and morph in response to sound. They form into partially recognizable forms — a bus or a face, for example — before changing again. The explanation of how the images are created involves machine learning, deep neural networks and data from fMRI scans. The effect is to give us a glimpse of what dreams may look like if we could record them

Atsuko Mochida’s “A Floating House” is a response to the numerous vacant properties that can be found on the island and that are an increasing fact of life around Japan generally.

Mochida has arranged for part of an empty house to be separated from the ground and raised up on jacks by about a meter. The inside of the house — with bric-a-brac, family photos and decorated fusuma (paper door) — seems to have been untouched for decades, and the whole effect is haunting and powerful.

Algerian-born artist Phillipe Parreno’s “Mont Analogue” is a combination of deep booming sounds and synchronized pulses of unfocused colored lights projected onto wall-sized silvered panels set in several disused classrooms of a local school. This sounds like it could be many other projects in rural art events in disused properties around Japan, but a few things set this work apart.

One is that the light pulses are coded to spell out the words of Rene Daumal’s 1952 French novel, “Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing”; another is the strength of the sounds that a powerful enough to feel like seismic events; and, lastly, the setting of the school itself, which, being of the older wooden variety, is particularly evocative.

Zon Ito and Ryoko Aoi’s “When the Field Floating Above the Ocean Begins to Make, the Shop on the Ship Begins to Send Word” and Austrian Lois Weinberger’s work around the island are very challenging in quite a different way.

Ito and Aoi have cut out a clearing a few minutes’ walk inside a forest, and started weaving nets, forming clay objects, and making flags from scraps of cloth they’ve found on the island.

Weinberger, who is more advanced in his artistic career, has created a little garden with a collection of buckets, and another that is a square plot of soil with nothing planted in it, bounded by gray office doors set on their sides.

If these works did not have information panels next to them, they might be indistinguishable from all the odd stuff that generally seems to accumulate in people’s yards or get dumped in the middle of woods and wastelands.

The challenge is that we can say random junk — or anonymous sculptures/ready-mades, if you like — is no less interesting if you are really serious about erasing the distinction between art and daily life. I am advocating aimless walks here, rather than criticizing the ambiguous nature of these works of art.

It’s also worth mentioning that an awful lot of walking or driving is required to move around the festival site. It’s far from barrier-free, and the amount of walking — without easy access to convenience stores or sometimes even vending machines — might prove tough for some in hot weather. In part, the distribution of the work is determined by what spaces are available, but the festival also wants to promote tourism and interaction beyond visitors merely coming to look at art pieces.

On this last point — providing a point of contact between the local community and visitors — “Peach Beach Summer School” by Tohru Nakazaki is an extraordinary achievement. While many works at Reborn-Art Festival 2019 aim, understandably, to be positive and cheer people up, Nakazaki’s in-depth research into local history, combined with a large inventory of found objects, is moving and respectful in a different, more solemn, way.

Festival staff member Harumi Shimura’s family had been living in the nearby city of Higashi-Matsushima when the tsunami struck. Nearly all of the houses in her neighborhood were swept away, although her immediate family did not suffer any fatalities.

“The festival is an important opportunity for Ishinomaki,” Shimura says. “It gives people a positive reason to visit other than just to look at the construction work and feel that they’ve visited a disaster area. Art is something they can enjoy, and it allows us to go beyond being just associated with tragedy.”

When asked whether local people took the time to visit the festival, Shimura says: “Most visitors come from Tokyo and other areas. People who live here get involved in other ways — namely, selling food and staffing the tours.”

That said, she expects that audience numbers from the local population will almost certainly rise during the Bon holiday season.

As for which piece she would recommend, Shimura highlights the sound piece by musician Ichiko Aoba.

“It’s something that a lot of people can experience at the same time, as it’s broadcast in the open air,” she says. “Aoba has created a special jihō (public time signal broadcast that can be heard in rural areas daily at 8 a.m., noon and 5 p.m.). A lot can be read into it. Everybody recognizes it and yet it’s still very open to interpretation.”

Reborn-Art Festival 2019 runs through Sept. 29 at locations near Ishinomaki, Miyagi Prefecture, and the Oshika Peninsula. Reservations have opened for one-day, English-language tours: https://campaign.japantimes.co.jp/raf2019. Subscribers to The Japan Times are entitled to receive a commemorative souvenir. For more information about the festival in general, visit www.reborn-art-fes.jp/en.