CULTURE

Hokusai: Examining the enduring allure of a Japanese icon

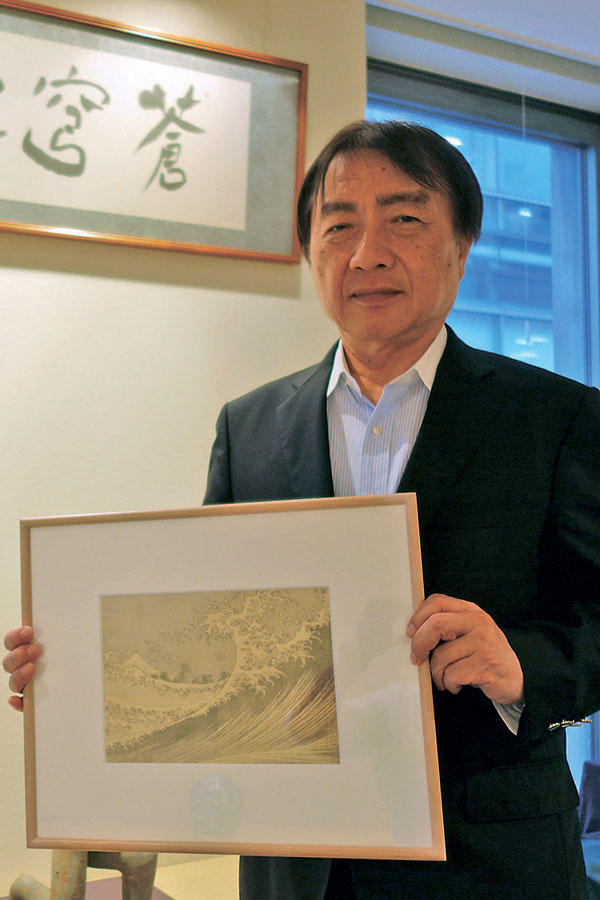

“Under the Wave off Kanagawa” (from the series “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji”) KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI

Hokusai’s thirst for new forms of expression and willingness to abandon established techniques in pursuit of an artistic vision continues to intrigue the world today

ALEX MARTIN

Staff writer

The year is 1842 and the artist known as Hokusai is in his 80s.

He has already lived nearly twice the average life span of his peers, but his advanced age hasn’t stopped him from embarking on a 250-kilometer journey from Edo to Obuse, a small, scenic town sitting in a mountain-ringed basin in present-day Nagano Prefecture where his patron and one-time student, a wealthy merchant-farmer by the name of Takai Kozan, awaits.

No one knows what went on in the octogenarian’s mind as he made the week-long trek starting with the inland Nakasendo route, followed by the Hokkoku Kaido, a secondary road developed for pilgrims making their way to the famed Zenkoji Temple in Nagano.

By this time, Hokusai was already one of Japan’s most prominent artists, and his works had begun penetrating the West.

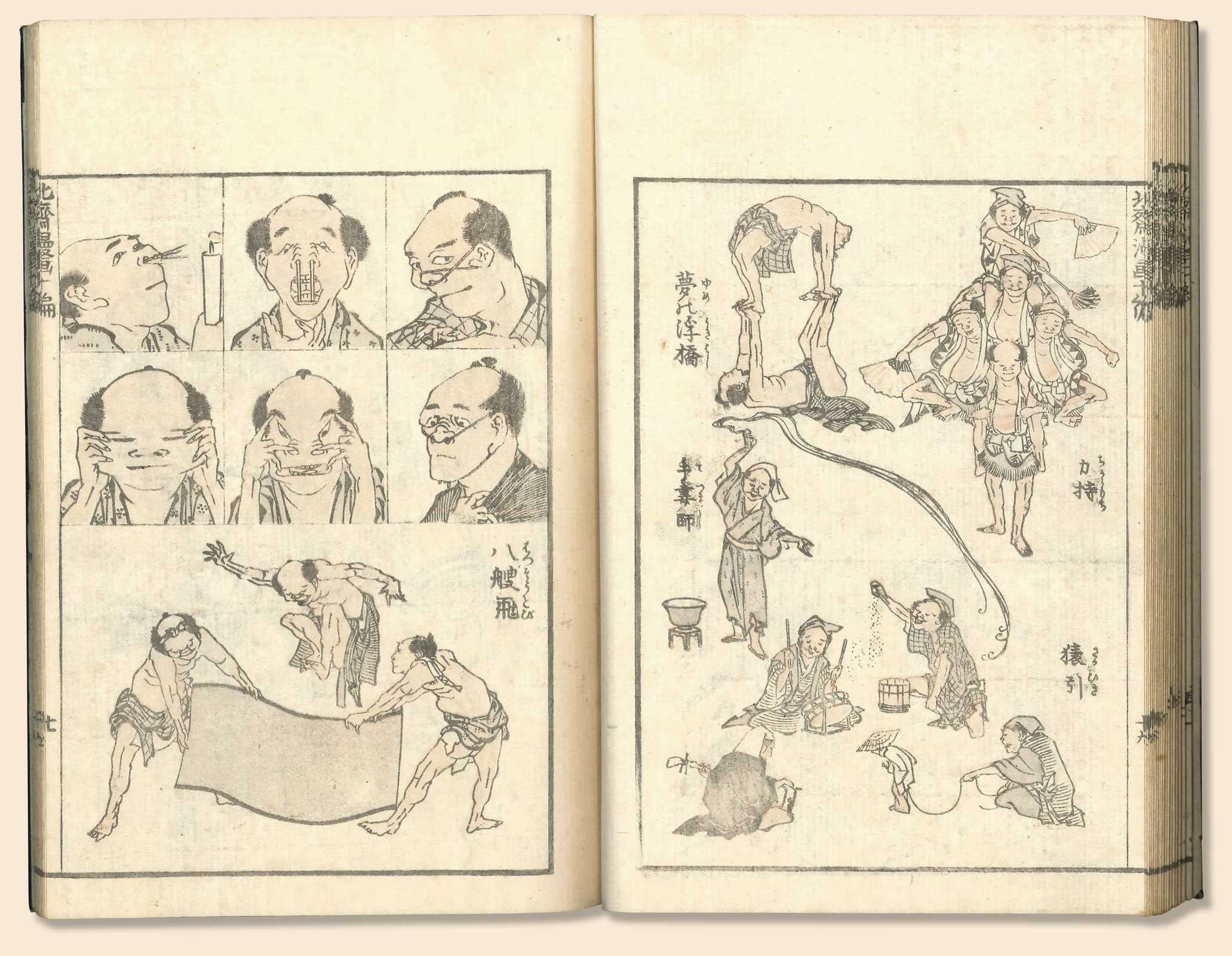

He was in his mid-50s when he published the first installment of what would become a 15-volume collection of thousands of sketches of geisha, landscapes, animals and everyday urban-dwellers in woodblock print known as “Hokusai Manga.”

The books would make their way to Europe with the help of German physician Philipp Franz von Siebold and his colleagues, touching off the Japonisme movement that inspired artists such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Vincent Van Gogh in the years to come.

He was in his 70s when he began releasing an ukiyo-e landscape print series known as the “36 Views of Mount Fuji.” The iconic “Under the Wave off Kanagawa,” better known as the “Great Wave,” would come to symbolize Japanese art globally, drawing comparisons with Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa,” and spawning endless homages and parodies to this day.

For the last leg of the journey, Hokusai would connect to the Ozasa Kaido route to take him to Obuse, where he would return several more times at the behest and funding of Kozan to devote his twilight years refining the art of brush painting, breaking away from ukiyo-e to produce some of his final masterpieces.

He would die in 1849 at the age of 88 in Asakusa.

During his lifetime, Hokusai assumed at least 30 names and is said to have moved residence 93 times, producing 30,000 designs over the course of his seven-decade career. At times living in poverty and famously nonchalant about his appearance, Hokusai didn’t drink or smoke, wasn’t sociable, was once hit by lightning and had a disregard for authority.

Perhaps it’s that restless spirit, his seemingly insatiable thirst for new forms of expression and willingness to abandon established techniques and norms in pursuance of an artistic vision that continues to intrigue the world today.

In an oft-recounted episode from his final days, Hokusai is said to have complained of his mortal constraints.

“If only heaven gave me another 10 years,” he said. Then, after a pause, continued, “If heaven gave me another five years, I could become a true painter.”

“Ejiri in Suruga Province” (from the series “36 Views of Mount Fuji”) KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI, COURTESY SUMIDA HOKUSAI MUSEUM

As the 170th anniversary of his death approaches next year, the legacy of the artist who called himself the “Old Man Crazy to Paint” is being revisited across the globe in various forms, from museum exhibitions and Hokusai-inspired apparel, souvenirs and beer to a new Japanese passport being designed that will feature his most well-known works.

The artist’s expeditions to Nagano are also being retraced as a modern-day pilgrimage. Organized by a group of Hokusai aficionados calling themselves the Hokusai Summit Japan Committee, a 10-day tour kicked off Sept. 6 from Tokyo’s downtown Sumida district where he was born.

Over the next nine days, the pilgrims made their way toward Obuse, taking part in woodblock workshops, bathing in hot springs and attending a classical concert along the way.

Led by award-winning nonfiction writer Norio Koyama, the Hokusai Summit is hoping to make the pilgrimage an annual event and a tourist draw, while expanding routes to follow places Hokusai may have visited when composing the “36 Views,” including the city of Fuji in Shizuoka Prefecture.

“I’ve traveled around Japan and the world to find out more about Hokusai and came to realize that he is more popular in the West than back in his home country,” says Koyama, who published a book titled “Shirarezaru Hokusai” (“The Unknown Hokusai”) in July.

Indeed, Hokusai appears to occupy a special place in the hearts of overseas fans of Japanese art.

He was the only Japanese given a place on Life magazine’s “100 Most Important Events and People of the Past 1,000 Years,” which was published in 1998. Last year, the British Museum held a much-lauded exhibition titled “Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave” and released the first U.K. film-biography of the artist, co-produced with NHK and featuring David Hockney and Maggi Hambling.

That’s not all. Over the past decade Hokusai exhibitions have been held at museums in Berlin, Paris, Boston, Rome, Tokyo and Osaka, while his motifs have been used in clothing brands ranging from Uniqlo to Christian Dior.

“I believe Hokusai is worthy of becoming another pillar of tourism for Japan alongside Mount Fuji, Kyoto and Tokyo,” Koyama says.

Researching for his book, Koyama visited the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, Italy and Germany, and talked to a dozen curators and museum directors about Hokusai’s allure and mystery.

His travels led him to who he considers a key figure in Japonisme: Tadamasa Hayashi, whose bronze facemask Koyama found exhibited in the Musee d’Orsay in Paris.

Hayashi was born in 1853, four years after Hokusai’s death, and was a Paris-based art dealer credited for introducing traditional Japanese art, including numerous ukiyo-e prints, to European art communities.

He first crossed the sea as a translator for a Japanese trading house to help coordinate its presence at the 1878 Paris World’s Fair. He decided to stay after the event’s success and opened his own boutique in 1884, selling high-quality oriental art to the burgeoning number of artists enchanted by the exotic crafts and paintings he would ship from Japan. His work led him to become acquainted with a number of French artists, including Degas and Monet.

In the decade from 1890, he is said to have brought 156,487 ukiyo-e prints and approximately 10,000 picture books from Japan to Paris, which included many by Hokusai, who by then was an established name among European art circles.

French art critic Theodore Duret declared Hokusai “the greatest artist that Japan has produced” in a story he published in the prestigious Gazette des Beaux-Arts magazine in 1882. The following year, the chief editor of the magazine, Louis Gonse, would praise Hokusai in his book on Japanese art, comparing the versatile master to Rembrandt, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Francisco Goya and Honore Daumier.

The recognition was in stark contrast to how ukiyo-e and Hokusai’s works were perceived by Japanese academia and Japan-based Anglo-Saxon connoisseurs who still considered the art form vulgar with limited value.

That difference in evaluation allowed Hayashi to purchase ukiyo-e for small sums in Japan to be sold at much higher prices in Europe, leading some to label him a ruthless opportunist. Hayashi would, however, work to raise the stature of the art form back home, producing ukiyo-e exhibitions in Japan and preaching how the genre was highly regarded in France and warning how important pieces could be lost unless its true value is appreciated.

“In a sense, Hayashi was an evangelist of Japanese art, both in Europe and in Japan,” Koyama says.

One of Hayashi’s collections, a 7-meter-long emaki picture scroll depicting a panoramic view of the Sumida River drawn by Hokusai, was featured in the first temporary exhibition held in the Sumida Hokusai Museum in Tokyo, a building designed by world-renowned architect Kazuyo Sejima that opened its doors in November 2016.

The scroll went missing after appearing in a 1902 sales catalogue of Hayashi’s collection, and took over a century for it to resurface at a London auction in 2008. Sumida Ward purchased the piece in 2015 and returned it to the museum.

The institution now has around 1,800 works, featuring those from the collection of late art historians Peter Morse and Muneshige Narazaki, as well as prints and paintings by Hokusai and related artists acquired by the ward prior to and following the completion of the museum. There is also a life-size model of Hokusai’s modest studio with robotic mannequins depicting the artist and his daughter, Oi, at work.

Mitsuaki Hashimoto, director of the museum, puts Hokusai’s appeal down to his inclination to break out of his mold to experiment with new concepts and techniques.

“When Hokusai was in his 70s, a promising artist by the name of Hiroshige began stirring up the art scene, catching the elderly painter’s attention,” Hashimoto says, referring to the ukiyo-e master known for the woodcut print series “The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido.”

“But while Hiroshige conformed to the tastes and sensibilities of the time, Hokusai was driven to break free,” he says.

Sandy Kita and Takako Kobayashi’s article on the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh website titled “The Bohemian vs. The Bureaucrat” may sum up the intrinsic difference between the two.

“Hokusai was a prime example of the independent and bohemian artist, and Hiroshige, 37 years younger, typified the artist of the establishment. They might view the same scene, but they would see different things,” the article says.

“A Mild Breeze on a Fine Day” (from the series “36 Views of Mount Fuji”) KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI, COURTESY SUMIDA HOKUSAI MUSEUM

Hokusai’s hunger for change is evident in his footsteps.

He is believed to have been born named Kawamura Tokitaro in 1760 at Honjo, which is located in eastern Edo (present-day Tokyo). Adopted by Nakajima Ise, a mirror smith working for the shogunate, he began painting at the age of 6.

At around 1774, Hokusai began learning the craft of woodblock printing before leaving his job in 1779 to join the atelier of Katsukawa Shunsho, the revered head of the so-called Katsukawa school of ukiyo-e, assuming the name Katsukawa Shunro.

Here he would produce his first prints, a series of 82 designs of kabuki actors. Shunro gradually explored uki-e (floating pictures) designs of landscapes using Western vanishing-point perspective techniques. His master, Shunsho, passed away in early 1793 and Shunro parted ways with the Katsukawa school, delving into surimono, limited-edition high-end prints circulated privately.

By 1794 he would adopt the name Sori, in homage to Tawaraya Sori, an artist of the Rinpa school, and some years later introduced the alias Hokusai, for which he is best known today. In around 1805, he added the title Katsushika, drawing from his native district of the same name.

For the remaining half century, he would produce designs under various pseudonyms covering the gamut of ukiyo-e, from single-sheet prints, picture books and illustrations for historical novels to erotic art known as shunga and hand sketches and paintings.

“Hokusai was not only a master of prints and illustrations, but was also something of an entertainer and a savvy self-promoter, and would participate in events where he would draw gigantic paintings before festival crowds,” Hashimoto says.

“On the other hand, he once painted tiny sparrows on a grain of rice. He could do anything — he designed sword guards and combs and was even involved in architecture, and I believe that versatility and how he doesn’t seem to be restricted to the world of ukiyo-e is part of his appeal.”

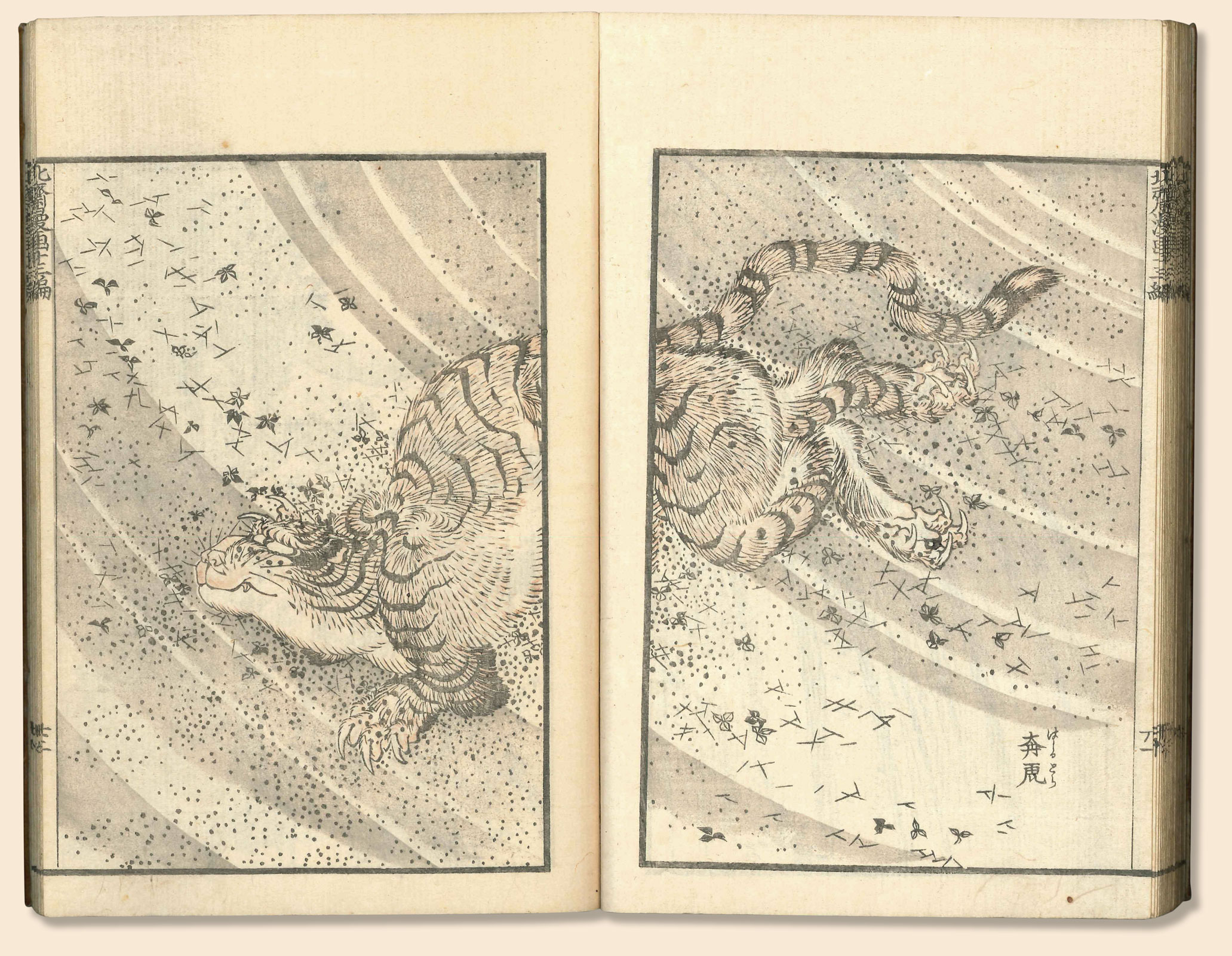

In 1814, he began publishing what is now known as “Hokusai Manga,” a compilation of sketches in 15 books that some consider one of his greatest achievements. Released over a 64-year period until 1878, Siebold brought back the first 10 volumes to be exhibited in his museum from 1837, introducing the artist’s work to Europe.

Encyclopedic in range, the books depict birds, insects and ghosts among numerous other subjects and contain Hokusai’s early experiments in portraying Mount Fuji from various angles. It would go on to define Japan’s image for the West in the 19th century.

“The European trend for Japonisme began, most improbably, when pages from a volume of ‘Hokusai Manga,’ allegedly used as packaging material in a crate of porcelain, turned up in the workshop of the master printer August Delatre between 1856 and 1859,” writes Rhiannon Paget in her book, “Hokusai,” referring to the discovery that will connect early impressionist artists such as Manet and Felix Bracquemond to Japanese art.

Mitsuru Uragami, founder of the antique art dealership Uragami Sokyu-do Co., bought his first volume of Hokusai Manga when he was 18 for what was then a hefty price tag for a freshman college student: ¥10,000.

Since then, the 67-year-old has accumulated around 1,500 copies of the illustrated books, making him the world’s foremost collector of “Hokusai Manga” and a frequent collaborator with museums and galleries, including the British Museum and the Tokyo National Museum.

Uragami says the immense popularity of the books meant they have undergone many reprints over the years.

“The first print is always the best, since the more prints you make the poorer the condition will become of the printing blocks,” he says.

“For example, the fine details of a woman’s eyes become blurred and even wiped out in later prints,” he says. That means earlier prints in pristine conditions better reflect the true scope of Hokusai’s art, which Uragami believes culminated in “Hokusai Manga.”

While Hokusai is now a national icon, Uragami says the artist has historically been more popular in the West. In fact, a third of Uragami’s collection are copies purchased from overseas.

“We used to compare Hokusai to Akira Kurosawa (1910-98),” he says, referring to the internationally acclaimed Japanese film director. “They were both more famous outside of Japan.”

That no longer appears to be the case, as Japan embraces the eccentric artist as an important cultural draw.

Starting next year, Japanese passports will incorporate 24 of the “36 Views of Mount Fuji.” Hokusai is featured in popular online games including “Fate/Grand Order” and “Monster Strike.” His daughter, a painter called Oi, who was also known as Oei, was the inspiration for the 2015 anime film “Miss Hokusai,” based on a manga series by Hinako Sugiura.

There’s even a female performance outfit dedicated to Hokusai called Katsushika Futome and Gyorome, whose names roughly means “chubby” and “goggle-eyed” in Japanese — a self-deprecating take on their physical traits inspired by how Hokusai is said to have called Oi “chin” in reference to his daughter’s protruding jaw.

The two perform comedy skits and navigate casual Q&A sessions on Hokusai at various events and venues, including the Sumida Hokusai Museum.

“With all due love and respect, Hokusai was a weird old man with countless interesting episodes that can be shared,” Gyorome says.

“For example, he didn’t drink or smoke but loved eating daifuku mochi desserts. And at one point, his name got so long that it was comprised of 13 characters,” she says. The two have a song to their name called Hokusai Manji Rhapsody composed from all of Hokusai’s known aliases. (Listen to a YouTube version in English.)

The duo performed on stage at various stops along the pilgrimage, which wrapped up on Sept. 16 at Obuse. Participants spent the next day admiring Hokusai’s artwork displayed in Obuse’s own Hokusai Museum, including two festival floats whose ceilings Hokusai illustrated with a dragon, a phoenix and his signature waves.

Outside the town center, there is a large mural of a phoenix painted on the ceiling of Ganshoin Temple, one of the final large pieces the artist left before his passing. Visitors are advised to lay flat on their backs on tatami mats to admire the full scale of the legendary creature that is said to be staring in eight directions.

Koyama, the nonfiction writer who led the pilgrimage on foot, says Hokusai’s longevity and tireless pursuit of his art serves as a role model in modern times when the average life expectancy has increased substantially compared to when the artist was active in the 19th century.

Hokusai himself spent his years anticipating old age. His artistic manifesto, written in 1834, ends with this prophecy: “When I am 100 years old, I will have attained a mysterious level, and at 110, every dot and stroke will be alive.”