LIFE

Danchi highlight complexity of Japan’s interculturalism

Shibazono Danchi (public housing complex) in Kawaguchi, Saitama Prefecture. YOSHIAKI MIURA

Aging public housing units juxtapose traditions of elderly Japanese with lifestyles of young international residents

SAKURA MURAKAMI

Staff writer

Stroll through Shibazono Danchi in Kawaguchi, Saitama Prefecture, on a weekend and you will find children shrieking with glee. They run across its communal playground or splash about in the fountain of the public housing complex as elderly residents enjoy leisurely walks in the background. Apartment blocks as high as 15 floors, their balconies dotted with drying laundry, tower over a courtyard lined with trees.

But what one might find unusual about the scene is that the children speak Mandarin, sometimes interspersed with Japanese, as their mothers converse in rapid-fire Chinese.

Such scenes are expected to become more prevalent nationwide after the government introduces a new residential status for foreign newcomers in April. The move is part of measures aimed at securing much-needed labor as Japan’s working population dwindles.

As Japan moves ever closer to becoming a more ethnically diverse and multicultural country, aging danchi residents are already grappling with the complexities of how to live with new, young tenants from different cultures. Their trials and tribulations offer insight into how Japan will cope with an expected influx of young, foreign workers in a graying country with limited experience in hosting blue-collar workers.

“Half of the 5,000 or so residents of this danchi are foreign nationals under 30, while the remaining half are Japanese people about 60 or over,” said Shibazono resident Hiroki Okazaki, 37. Over 90 percent of the non-Japanese residents are believed to be Chinese, he added.

“This place is like a representation of what Japan will look like in the future, just on a smaller scale,” said Okazaki, a member of the danchi’s resident association.

Indeed, a number of public housing complexes across the country have become home to two very different demographics — young foreign residents and elderly Japanese.

A large number of elderly Japanese danchi dwellers tend to have lived in them for decades. Many moved in during a nationwide rush to build the housing units in the ’60s and ’70s to address the significant dearth of housing at the time. These residents remained after watching their children grow up and move out.

But danchi also serve as an attractive housing option for non-Japanese, not only because of the affordable rent and deposit-free contracts, but also because of their receptiveness in a housing market where discrimination is widely seen as rampant.

A Justice Ministry survey released in 2017 found that about 40 percent of foreign residents had been refused tenancy at some point in Japan because they weren’t Japanese.

These factors have combined to help create a number of housing complexes that serve primarily as homes to foreigners and elderly Japanese.

All figures as of September 1st of that year. SOURCE: KAWAGUCHI CITY. JAPAN TIMES GRAPHIC

But at times, differences in lifestyles and habits have caused friction at these danchi.

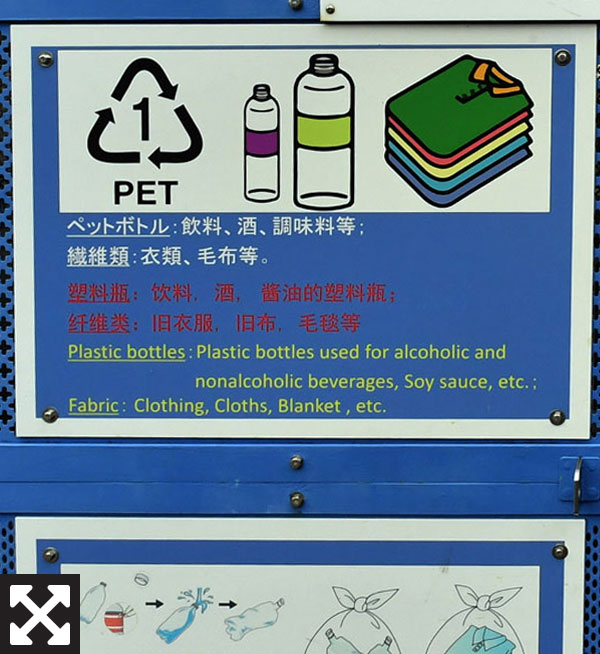

In Shibazono’s case, a tabloid magazine reported in 2010 that the complex, situated in the city’s Shibazonocho district, was turning into a “China Danchi,” detailing complaints from Japanese about how foreign tenants failed to heed basic rules on how to throw away their trash, in some cases allegedly tossing litter from their windows.

“I do agree that in some cases the incoming residents can be rude about how they throw things away,” said Kim, a 38-year-old woman from Northeast China who asked to be identified only by her last name. She lived in the danchi for about five years before moving out four years ago.

That being said, she noted that there was a significant cultural difference in how litter is thrown away in China and Japan.

“You’re the one who has to pay when you throw away things like electrical appliances or furniture in Japan, but in China there are people who are willing to buy what you’re throwing away,” she explained, saying it meant waste disposal in China is basically free, if not an opportunity to earn a bit of extra cash.

The waste-disposal issue is usually one of the first that residents grapple with when dealing with foreign arrivals, explained Yoshiko Inaba, a lecturer at Tokyo’s Hosei University who is an expert on residential issues.

“New foreign residents might come from countries where they don’t need to sort their waste. … It’s very hard to explain Japan’s waste disposal system to people who come from such diverse backgrounds,” she said, adding that it’s just as important to explain the “why” aspect of the rules to newcomers so they better understand.

Still, Shibazono has come a long way since the complaints made headlines.

“The situation has improved” over the past decade or so, and waste and noise issues are not as prominent as before, said Katsuji Nirasawa, a 74-year-old resident who leads the danchi’s resident association.

The improvement is likely due to a combination of factors, including efforts to build better relations with non-Japanese. These efforts were largely undertaken by the resident association and a university volunteer group called Shibazono Kakehashi Project, which aims to build kakehashi (bridges) between different cultures.

In 2012, the danchi’s management company agreed to station a Chinese interpreter at the complex. Events were planned to promote understanding between residents, culminating in the 2015 launch of the Shibazono Kakehashi Project. Its aim was to bring residents together, regardless of age or nationality, for gatherings and events on a more regular basis. It also sought fresh perspectives from the student volunteers themselves.

And yet, despite the drastic improvement in relations, residents still seem to maintain a quiet distance from one another.

“The resident’s association has worked so hard to improve things for us, but I don’t think everyone understands that,” said Fujii, a middle-aged female resident who asked to be identified only by her last name.

“The thing is, the Japanese and Chinese residents don’t ‘live together,’” she said, using the Japanese word kyōsei, a term that implies a certain level of good relations and mutual dependence.

“We merely coexist.”

This stable but somewhat awkward coexistence may be a success in its own right, depending on how you look at it, said Mika Hasebe, an associate professor at Yokohama’s Meiji Gakuin University who is also involved in a nongovernmental organization that promotes better residential relationships at a danchi in Kanagawa Prefecture.

People dance during a summer festival at Shibazono Danchi in Kawaguchi, Saitama Prefecture, in August. SAKURA MURAKAMI

Icho Danchi, built in the early ’70s as public housing, saw an influx of foreign residents from about 1990 onward, with the bulk of them initially hailing from Vietnam and Cambodia. This was partly because a refugee support center for Indochinese refugees was located nearby.

With 20-plus years of experience dealing with foreign residents, Icho Danchi has set itself apart from similar danchi by getting its resident association, a local NGO and a primary school to collaborate on integrating them into the community.

Hasebe said that although this has helped resolve cross-cultural issues, part of the reason tensions between residents have subsided is also because “the elderly simply get used to the situation.”

“It’s not like the residents are on really good terms with one another, but you end up accepting the situation,” Hasebe said.

The lack of common values to unite danchi residents isn’t just an issue of nationality or culture, it’s also one of generational differences.

“Obvious and highly visible issues like people littering or being loud late into the night have definitely decreased” at Icho Danchi, said Hasebe. “But the elderly continue to grow older, and some become isolated and die alone. The non-Japanese residents are now growing older, too. … The issues that the danchi have aren’t as visible now, but they haven’t been completely resolved either.”

Some aging longtime residents voiced resignation with the current state of affairs while wistfully recalling a time gone by.

“This danchi has changed,” said 85-year-old Ichi Kawaguchi, a nearly 40-year resident of the complex.

“People don’t help each other out as much anymore,” she said. “In the past, we were all on good terms, saying hello and asking how each other’s day was.”

But Kawaguchi says the lack of communication with her current neighbors, regardless of whether they are Japanese or not, doesn’t make her sad.

Some neighbors can “get on your back if you get too close. They bad-mouth you behind your back. That’s why it’s easier to chat with people you aren’t so close with,” she said as she sat on the grass conversing with a fellow resident she’d just met.

Back when danchi were thriving, the residents were of the same generation and had similar lifestyles, said Inaba, the Hosei University lecturer.

“That meant even if your upstairs neighbor’s children were noisy, it was a bit of give and take for everyone.”

But those demographics aren’t the case with the danchi’s current residents.

“Now there are families with young children residing with an elderly generation that wants peace and quiet,” said Inaba. “And on top of that, they don’t necessarily speak the same language.”

The issue is multilayered because it “isn’t just about nationality, but also about generational gaps,” she added.

Okazaki of Shibazono Danchi’s resident association drew a similar conclusion through his voluntary work there.

“The ‘culture’ in ‘interculturalism’ is often used to refer to one’s national culture, but when you actually think about it, different generations have different cultures as well,” he said.

The tendency of foreign newcomers to be young and highly mobile also means they tend to view the danchi as a temporary residence rather than a permanent home like the elderly Japanese.

That means new relationships have to be built and the rules have to be retaught each time, making for a seemingly endless — and exhausting — process.

“I haven’t had the chance to get to know the residents here because I’m always so busy with work,” said Cao Liangliang, a 30-year-old architect who has lived in Shibazono Danchi for about a year.

He said he was planning to move back to China next year because he wanted his 3-year-old child to learn Chinese, and because he had high hopes for China’s economy.

Residents make their way through the giant housing unit’s courtyard on Friday. The unit’s demographic mainly consists of young, foreign families and elderly Japanese. YOSHIAKI MIURA

Keizo Yamawaki, a professor at Meiji University in Tokyo who specializes in immigration policy, believes that enacting a legal structure local governments can work under could help create a smoother and more effective integration process.

“Japan is far behind other countries in terms of promoting the integration of migrants because there is no law to serve as a basis for supporting newly settled foreign residents,” he said.

“Municipalities have had to go it alone in terms of providing support to incoming foreigners for some 30 years now. … The government needs to create a legal basis for promoting integration so municipalities can provide the necessary support,” Yamawaki added.

For Ichiro Watado, a professor emeritus at Meisei University in Tokyo who specializes in urban sociology, an awareness of the breadth of interculturalism is also key.

“It’s essential to be aware that interculturalism spans so many issues,” said Watado. From education and health care to laws and ordinances, we must take into account how multifaceted interculturalism is, he said.

Given these complexities, what can be done?

Residing with people from different cultures “can be difficult, especially because it makes lifestyle differences so apparent,” said Okazaki, the Shibazono resident.

“What it comes down to is knowing who your neighbors are,” he added. “It’s about maintaining a balanced relationship with your fellow residents.”

Akira Sasaki, 74, a retired postal worker who has lived in Shibazono for about 40 years, appeared to echo that sentiment, saying he had no misgivings about the increase in non-Japanese residents.

“My neighbors are foreigners and I don’t have any concerns about that. After all, I do have a few acquaintances here who are Chinese,” he said.

According to Inaba, interculturalism “is a continuous process, and there’s no final form or solution.”

But, she said, that also means the next time a non-Japanese arrives, the residents will already be familiar with the process.

“They will already know that they need to teach the newcomer the local rules,” Inaba said.

With immigration policies and diplomatic relationships between countries in constant flux, Inaba said, “There will always be setbacks. But you never go back to square one.”

Moreover, Hasebe said, because the process is one likely to be repeated many times, it’s essential to have fun so that it doesn’t lead to burnout — a point Inaba said she wholeheartedly agrees with.

“It’s very difficult to get along with people from such diverse backgrounds,” she said. “But you can’t forget that there are moments of fun, too.”

Interpreter Ellie Wong and contributing writer Aika Sato contributed to this report.

Every month Deep Dive takes an in-depth look at a topical issue in Japan.