A new generation of domestic media artists has in recent years attracted plenty of international attention. This new breed of artist is typically defined through their tools — often programming code — working as developers at the intersection of art, design, engineering and technology, among other things.

Most importantly, these artists also produce a variety of unique cultural works. Having grown up in an emerging do-it-yourself environment, they are technicians who hack and manipulate microcontrollers to create a wide range of eccentric machines and devices for interactive installations. They use sound, visuals and prototypes in artistic and commercial ways, thus permeating the established boundaries of genre.

Code may be the underlying foundation behind most of these artists’ works, but their individual output varies greatly. While modern media artists tend to use digital technology to produce their artwork these days, analog tools are still relevant and many continue to use both in order to create an eclectic body of work.

First, however, let’s step back a little and examine the artists and events that laid the groundwork for this movement to flourish in Japan.

The first hint that there was a clear affinity between art and technology came at the Pepsi Pavilion at the World Expo in Osaka in 1970, where Experiments in Art and Technology artists collaborated with engineers to design and program a geodesic dome that was obscured by a fog sculpture by artist Fujiko Nakaya.

Pop culture has consistently been at the forefront of media art’s evolution over the decades. In the late ’70s and early ’80s, new-wave outfit Plastics created a unique sense of fashion and sound that made the band stand apart from other domestic acts at the time. Transforming its image several times over its short existence, Plastics also experimented by using machines as instruments on a number of its tracks. (Plastics guitarist Hajime Tachibana is believed to have driven much of the creative endeavors the band is famous for, but this may be linked to the influential work he produced as a graphic designer after leaving the group.)

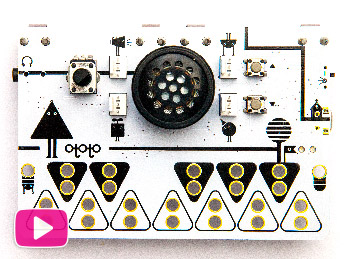

In the same vein, electronic trio Yellow Magic Orchestra pioneered the use of equipment such as samplers and synthesizers in the domestic music scene in the 1980s. In the mid-1980s, media artist Toshio Iwai started creating installations using computer graphics, video projection and stroboscopic LED lighting while also developing computer games at the same time. In 2007, he would go on to create an interactive digital musical instrument called Tenori-on in collaboration with audio-equipment manufacturer Yamaha.

A number of private and public institutions also helped recognize electronic art in the early 1990s, including the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography and the Canon ARTLAB. In 1997, telecommunications company NTT opened the NTT InterCommunicationsCenter (ICC) in Tokyo’s Hatsudai neighborhood, which has since garnered a reputation for being a space where technology is part and parcel of everyday life. That same year, the Japan Media Arts Festival also embraced electronic art after receiving support from the government’s Agency for Cultural Affairs. More recently, the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media, which opened in the city of Yamaguchi, Yamaguchi Prefecture, in 2003, has also helped promote the genre.

In hindsight, the 1990s was especially fruitful for three media artists who focused on playful experimentation with devices that sat at the intersection of technology, science, design and entertainment: engineer Hiroo Iwata produced quirky machines, Ryota Kuwakubo innovative minimalist game interfaces and Maywa Denki whimsical musical instruments. The latter is a pseudonym for Nobumichi Tosa and his so-called art unit who, clad in worker overalls, created “nonsense machines” for his musical performances. Initially owned by Sony Music Entertainment, Maywa Denki transferred its management to Yoshimoto Kogyo in 1998 as Tosa started to take a different approach to manufacturing and started to explore commercial opportunities.

Also that year, Kuwakubo designed a prototype of BitMan, an LED device that depicted a man dancing when shaken. The prototype later became an actual product that was manufactured and marketed in collaboration with Maywa Denki. Maywa Denki’s musical instrument series KnockMan, an orchestra comprised of figures that knocked, was marketed in a similar fashion in 2003.

By the mid-1990s, Ryoji Ikeda, a composer of electronic music and a visual artist, stood at the other end of the media art spectrum. His audio-visual performances were based around a mathematical aesthetic and minimalist style that more than likely continues to inspire up-and-coming artists today. As a longtime member of Dumb Type, he helped develop the multidisciplinary art collective’s electronic style as well.

Thus, media art has undergone massive paradigm shifts over the past 20 years.

“The Internet is the new museum (these days),” says Nao Tokui, founder and CEO of digital agency Qosmo Inc., who has worked closely with several of the media artists included in this article. “People have become used to artistic expression in digital formats thanks to the rise of smartphones and mobile Internet technology. A media artist these days doesn’t have to rely on established museums. Everyone essentially has a museum in his or her hand.”

To some extent, this is true. Since the emergence of a new art form called Internet art (often referred to as net.art) in the 1990s, almost anyone can use the Internet as a medium to create and display his or her work online. However, the Internet is a vast chaotic network that contains content that hasn’t been curated effectively. This has most recently led to the expansion of digital expression on new kinds of media such as smartphones and tablets.

Now that we’ve examined how media art has evolved, let’s look at the state of the genre in Japan today. In essence, four artists or agencies represent various facets of the contemporary community in the country: Internet duo exonemo, sound artist Yuri Suzuki, body scientist Daito Manabe and his Rhizomatiks collective, and teamLab, which has been embraced by the serious art world on the back of its mesmerizing digital projections.