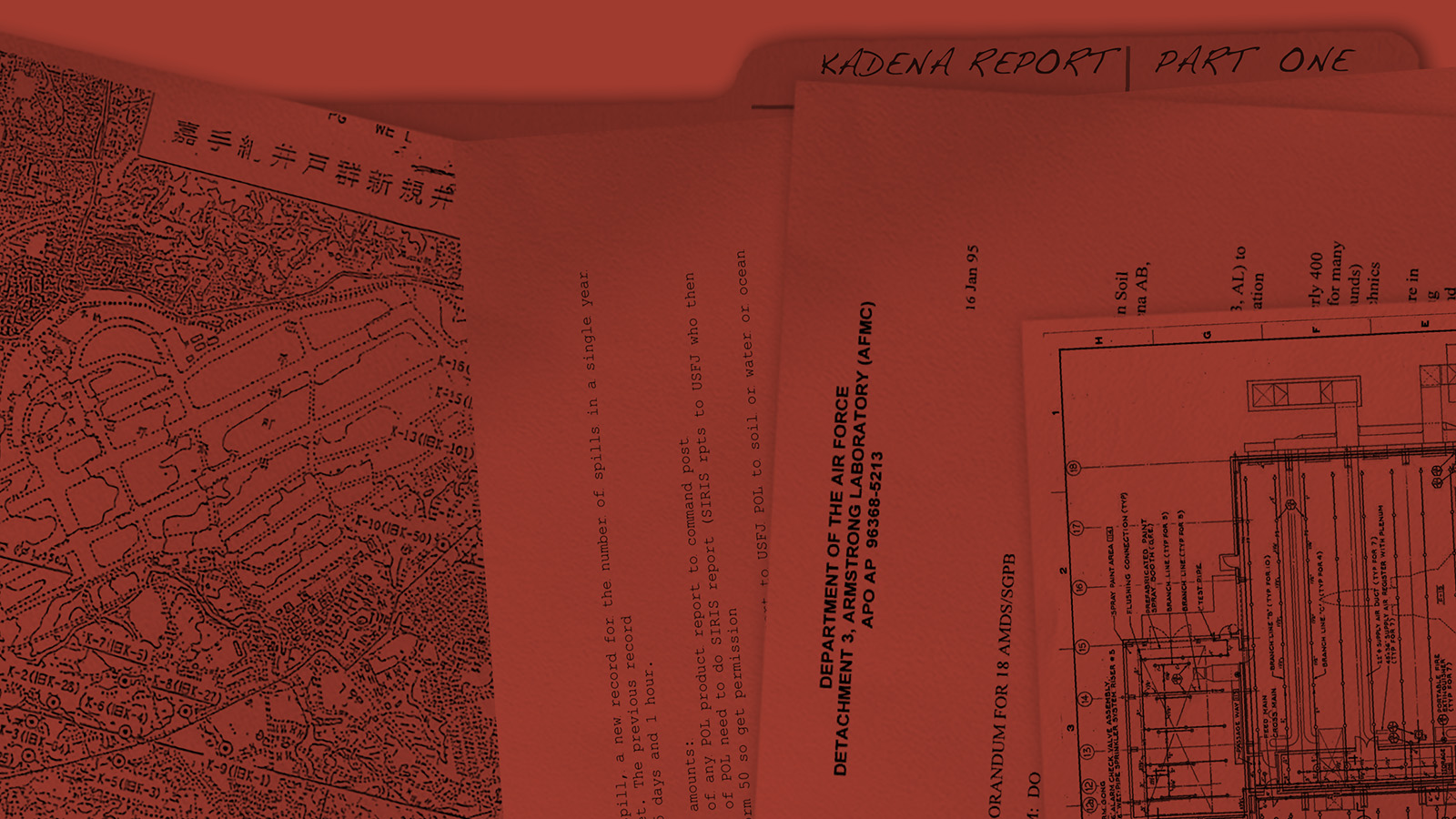

Lax safety standards at Kadena Air Base might now be returning to haunt the 20,000 U.S. Air Force members and their families living and working on the installation.

“John loved the air force,” said Jennifer Agger. “He was a true hero and a patriot who gave his life for his country. But he has received no recognition for his sacrifice because the military won't acknowledge the cause of his disease.”

Agger’s husband, John, spent a total of six years on Kadena Air Base, with his final tour ending in 2006. In 2014, at the age of 36, he died of pancreatic cancer.

Since the disease was so unusual for a man of his age, postmortem tests were ordered. They revealed levels of dioxin in his tissue so high, Dr. Greg Nigh noted, that “if found in a food, would be 2-3 times above the acceptable safety limited for consumption.”

The same doctor surmised: “The evidence seems to me very strongly suggestive of a link between John’s pancreatic cancer and his exposure to dioxins.”

Determined to alert current service members stationed at Kadena Air Base of the risks, Jennifer took the postmortem results to her Congress member, who contacted the U.S. Air Force.

“I received essentially a canned statement from the USAF,” she says. “Even after reiterating my concerns, I received a second letter that was word for word the same.”

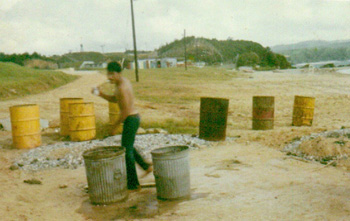

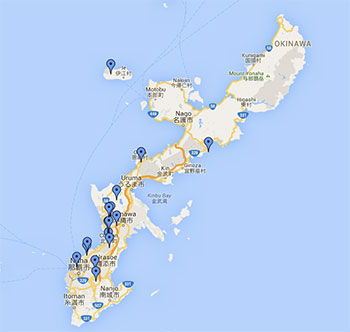

Such opacity seems sadly all too common. Among the veterans featured in five years of Japan Times coverage of this issue, three — including Goetz — have died waiting for the military to respond to their concerns and those of their families. Scott Parton, the shirtless marine pictured in the now well-known photograph of a barrel of Agent Orange at Camp Schwab, died in April 2013. Gerald Mohler, a marine exposed to herbicides near Camp Courtney in present-day Uruma city, died in September 2013.

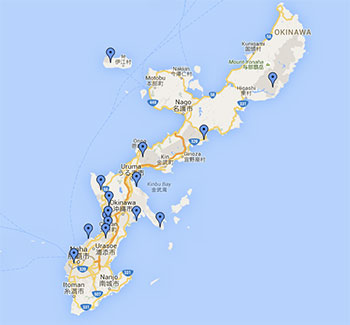

It seems Okinawan residents have also been exposed. In July 1968, 230 Okinawan children swimming at a beach in Gushikawa (also now part of Uruma) suffered chemical burns to their bodies. The shoreline had recently been sprayed with large volumes of Agent Orange to clear vegetation. At Camp Schwab, situated in Nago in the north, high rates of cancers among employees have been attributed to the defoliants they were ordered to spray in the 1960s and ’70s.

Given the persistence of dioxin below ground, it is unsurprising that the number of former military sites where it has been detected is rising: the soccer pitch in Okinawa City where 108 barrels were found, a residential area in Chatan, an old airfield in Yomitan, a shuttered military housing area at Nishi Futenma.

Because the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement does not allow checks within American bases, nobody knows the extent of dioxin contamination on currently operational U.S. installations. Likewise, the Okinawa prefectural authorities and Japanese government have never conducted any epidemiological surveys of local residents or former military employees.

Masami Kawamura, director of the Informed-Public Project, an Okinawa-based organization working on environmental issues, blames this on apathy at both the prefectural and national level. In 2012, prefectural officials indicated they would consider running health checks if firm evidence of contamination was ever found, she explains, “but even after high levels of dioxin were discovered in Okinawa City, they did nothing. It is as if they don’t want to create extra work for themselves.

“Also, Okinawa Defense Bureau tries to downplay the severity of contamination,” she says. “They take the side of the U.S. government over the side of Okinawan residents. That’s why they hire scientific experts chosen to deny the presence of defoliants.”