SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 9

Denuclearized

Three's company: A young family makes its way through the grounds of Shurijo Castle in Naha, Okinawa Prefecture, in June 2012. | ROB GILHOOLY

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the ninth installment of a series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades. This installment examines the shifting dynamics of the family in society

ROB GILHOOLY

Contributing writer

Hatsune is Akihiko Kondo’s dream wife.

Petite and animated, she always greets him with a cheery smile when he returns home from a hard day at work and selects his favorite TV channel. She even sings him a song and charges his phone.

She isn’t really one for washing, cooking or ironing, but, hey, it’s 2019 — he can see to that himself.

More importantly, Kondo says, is that Hatsune will “never cheat, age or die.”

It was after a decade-long infatuation that Kondo decided to pop the question to Hatsune Miku, a turquoise-haired, latex-clad hologram based on a moeanthropomorph who refers to her “husband” as “master.” After tying the knot in November, Kondo is convinced he’s found true love and happiness.

“There has long been a call for diversity in society,” says Kondo, a 35-year-old school administrator, after his ¥2 million wedding, which was sealed with an “exchange” of rings and a mock marriage certificate.

The conventional blueprint of a family — where a man and woman marry, have kids and live in a mortgaged house in the suburbs — is no guarantee of contentment, he says.

“I don’t believe happiness is limited to that template,” he says.

Kondo, who confesses to a lifelong struggle with relationships of the terrestrial variety, might be given short shrift as being little more than a so-called digisexual, for whom virtual reality contrivances are a way of bypassing human intimacy.

As we near the end of the Heisei Era, however, his observation might also be viewed as a telling aphorism of the times.

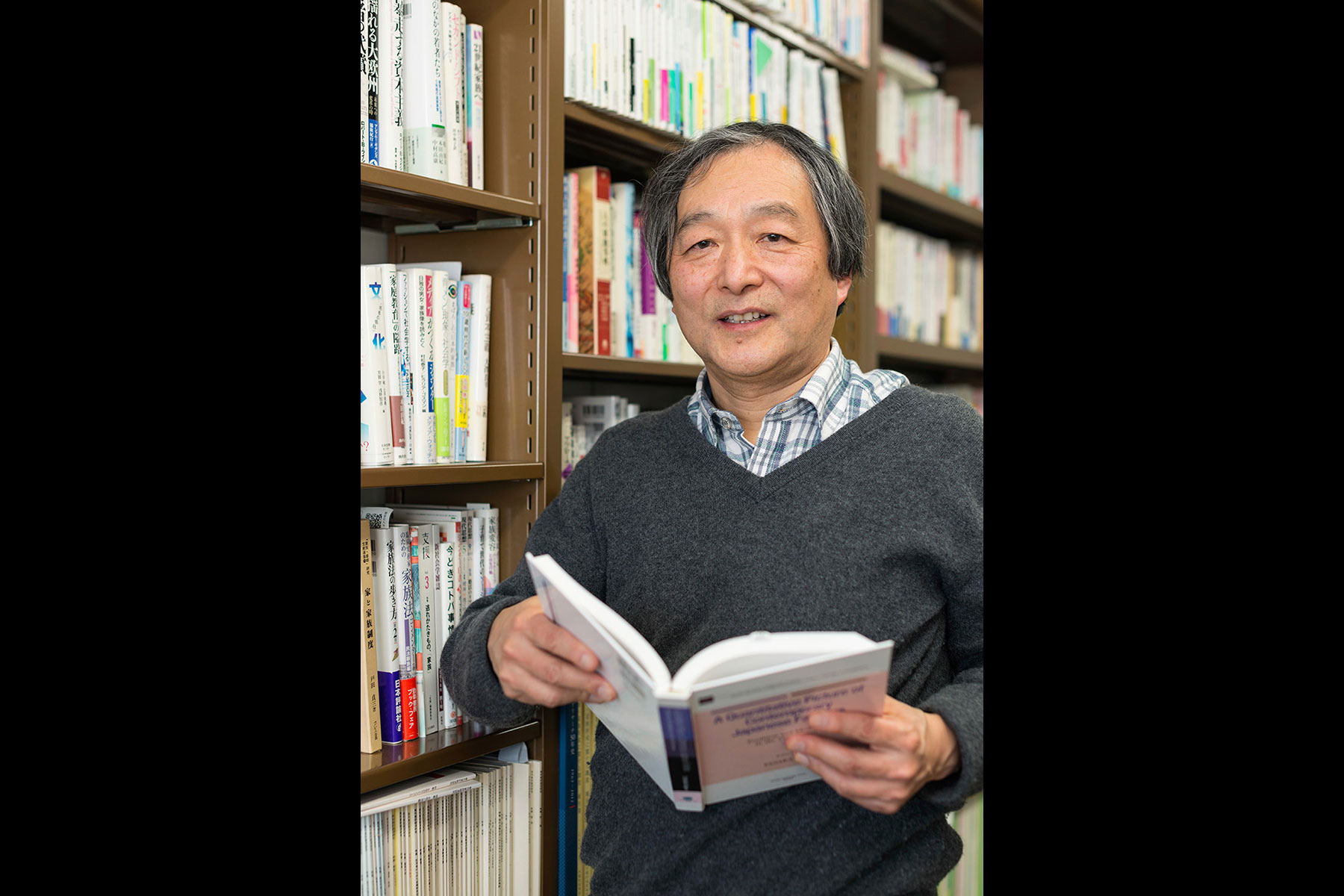

“When it comes to the Japanese family, the Heisei Era could be characterized as an era in which the conventional family was no longer seen as a social requirement,” says Takeshi Goto, a multimillion-selling author, historian and researcher of the Heisei Era, which draws to a close on April 30.

“For me, the period could be called ‘the quiet, turbulent era,'” Goto says. “It’s quiet in that, unlike in the preceding Showa Era (1926-89), there was no world war, but turbulent in that many systems put into place (in Japan) over decades and centuries came tumbling down. A prime example is the family system.”

Up until the economic boom years of the 1960s and ’70s, Japan emulated many other advanced industrialized nations, boasting a template of an “ideal” family that was built around a clear delineation of spousal duties.

The Japanese husband was more or less guaranteed — by what Goto calls an “unspoken promise” — lifetime employment and an adequate salary by companies locked into Japan’s gosō-sendan (convoy capitalist) system, which assured them an easy life provided they did as they were told by the government — the “convoy” that guided them to economic riches.

Pensions, health insurance — pretty much the entire social system, in fact — was designed to support the idea of the man as breadwinner whose wife was content to become a sengyō-shufu (housewife) with little incentive to find work outside the home.

In time, some homemakers would find part-time employment to support the often prohibitive pressures of a “better” education for their children, though not so much work that their husbands would be precluded from receiving haigūsha-kōjo (spousal tax breaks) and bonuses awarded by companies to male employees just for having a stay-at-home wife.

According to Masahiro Yamada, a professor of sociology at Chuo University, that “better” education was of little consequence as many of those children would simply become quasi-clones of their parents.

Like their fathers, sons would jostle for lifetime employment at a reputable company, while daughters’ ambitions were best summed up by the so-called sankō — the “three highs” — that defined an ideal man: kōgakureki(high education), kōshinchō (tall) and kōshūnyū (high income), Yamada says.

Women who struggled to land such a catch faced an additional, unwanted pressure: Marry before turning 26 or risk being labelled with the pejorative “Christmas cake” moniker.

“There was a particular kind of family that was promoted and many young people dreamed of having, and the backdrop to that was the growth of the economy,” says Yamada, who has coined numerous popular phrases for Heisei societal phenomena, including “parasite singles” and “konkatsu” (“matchmaking parties”).

“Men worked at businesses where employment and salary were stable, and married women who preferably were not so well educated as to spurn domestic duties,” Yamada says. “Families were economically comfortable and, unlike arranged marriages or those born out of economic necessity, marriages of love became more common.”

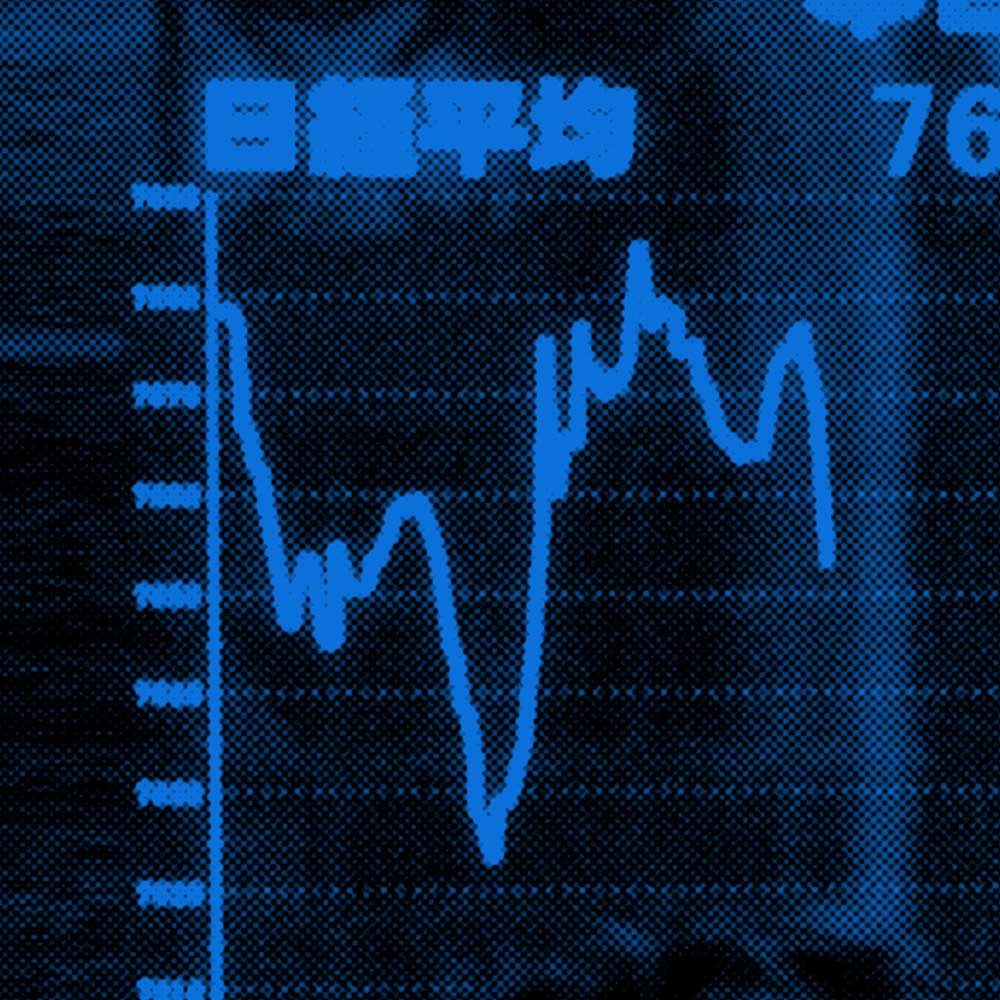

The 1973 oil crisis and subsequent post-industrial “new economy” put a dent in job stability and men’s previously unquestioned ability to support their families, but it wasn’t until the collapse of the economic bubble at the start of the 1990s that the “dream” Japanese family started to lose its la-la land lustre.

With the protracted economic downturn and progression of globalization in the ’90s, employment stability was undercut further still by deregulation of employment, which not only pushed up the number of nonpermanent workers, but curtailed salary raises and bonuses of those still enjoying permanent positions, Yamada says.

The percentage of men who were able to support their family fell to about the same level as the United States, where only about a third of families are supported by a breadwinner father and stay-at-home wife.

“However, unlike other developed nations, there was virtually no advancement in the diversification of the family in Japan,” Yamada says, adding that while mothers were gradually beginning to emerge as breadwinners in the United States (40 percent of households with children in 2011), the proportion of Japanese women raising children as housewives remained high, especially when compared to other advanced countries.

And even though an increasing number of women were working — around two-thirds of them part time, which increased their household contributions — men were still viewed as the breadwinners, meaning the core of the delineated family system remained largely intact, he says.

Nonetheless, the “turbulence” of the Heisei Era slowly nibbled away at the foundations and the Japanese “household” — the unit by which “family” has been measured since the first national census in 1920 — has changed considerably, first morphing from one accommodating two or more generations to those of childless and single occupancy, according to Goto.

Apartments and townhouses in danchi housing estates that were erected one after another in the growth years were essentially built with the nuclear family in mind and family members per household, which according to a national census totalled five in 1953, had almost halved by early Heisei to sit at 2.7 in 1997. This figure has since fallen to 2.2, according to statistics from 2018.

More recently the makeup of those households has changed again, with nuclear families giving way to a rapidly aging, low-fertility society in which households are increasingly occupied by relationship-shy singles, or couples.

Single-occupancy abodes have almost doubled since the end of the Showa Era (from 18.2 percent in 1986 to 34.6 percent, or 18.42 million households in 2015) of which nearly 6 million were occupied by over 65-year-olds — double that of the national census in 2000. Meanwhile, couples-only occupancy figures have increased two-thirds, from 14.4 percent to 24 percent, or 10.72 million, during the same period. Combined, these made up more than half of Japan’s 53.3 million households.

Conversely, households of couples with children have fallen from 41.4 percent to 29.5 percent over the same period and homes where three generations living under the same roof has plummeted from 15.3 percent to 5.8 percent.

Furthermore, homes where at least one child is present has fallen from 46.2 percent in 1986 to 23.3 percent in 2017, meaning that there are now no children in almost 77 percent of Japanese households (compared to 47 percent in 1975). Indeed, numbers of children have nosedived during the Heisei Era, with the population of under-15s falling from over 26 million in 1985 to 15.5 million in 2018.

One reason for this trend is a declining fertility rate, triggered by a fall in adults interested in marriage. In the most recent national census in 2015, 72.5 percent of men and 61 percent of women in the 25-29 age bracket were unmarried, while almost half the men and over one-third of the women aged 30-34 shunned matrimony.

Very few couples cohabit out of wedlock (just 1.6 percent in 2010, compared with 30 percent in France) and those giving birth outside marriage was 2.4 percent in 2014 (compared with 40 percent in the United States and 60 percent in France).

Young Japanese have also cooled on relationships. Of Japan’s 10 million young unmarrieds, 4 million say they don’t want a romantic partner, Yamada says.

Furthermore, 80 percent of 20-34 year-olds live with, and remain financially reliant on, their parents, Yamada says. These so-called parasite singles are also prominent in the middle-age bracket, many of them living off their parent’s pension “with little idea how they will survive the financial hardships they will almost certainly face after their parents pass away,” he says.

According to Chizuko Ueno, Japan’s foremost feminist scholar and author of more than 30 books, including “The Modern Family in Japan: Its Rise and Fall,” the numbers of people staying single for life actually started to make a mark at the beginning of the Heisei Era and have continued to rise since.

While in 1980, only 2.6 percent, or roughly 1 in 40 men, and 4.4 percent, or 1 in 22, women had never been married by age 50, by 2015, those figures had risen to 23.4 percent of men (just over 1 in 4) and 14 percent of women (1 in 7), government figures show.

“It is predicted that one-third of men and one-fifth of women now in their 30s will remain single for life,” Ueno says. “This is one reason why I call the Heisei Era ‘the age of the ohitorisama‘ (or ‘the age of being alone’).”

Another reason is the divorce rate, which although already on the rise from the late ’60s, shot up exponentially during the post-bubble years, jumping nearly 90 percent between 1988 and 2002, when it peaked at 289,836 divorces, or 2.3 per 1,000 of the population.

Even at that peak, however, it was still not conspicuously high by global standards (2.5 per 1,000 people in the United States), a detail that conservative experts often attribute to a particular stability of the Japanese family system, according to Ueno.

Ueno argues that, on the contrary, Japan’s high number of unmarrieds plus the declining fertility rate, which fell to a record low of 1.26 in 2005, are two other demographic indices that should be included in the equation.

“I interpret the former as a replacement for the divorce rate,” Ueno says. “In fact, I call it pre-marital divorce — you just don’t have to get married to get divorced in this case.”

The latter, meanwhile, is the equivalent of extramarital birth that is interrupted by abortion — which in Japan is easily accessible, safe and inexpensive enough to serve as a such an equivalent, she adds.

Furthermore, Japan’s divorce rate is considerably higher when calculated against the number of marriages, Ueno says. This is particularly true for those in their 30s — considered by sociologists to be particularly susceptible to divorce — where more than 1 in 3 are divorced, she adds.

“In the United States and other developed countries it’s said this figure is 1 in 2, so Japan is in fact getting much closer,” says Ueno, adding that the increasing number of single mothers (87 percent of Japan’s 1.42 million single parents are women) is another product of the surging divorce rate that has impacted the conventional family over the past 30 years. “It will probably continue to do so, especially as (divorce) is much less stigmatized than it once was.”

Nonetheless, Yamada believes old-fashioned views persist, reflected most notably in the negligible numbers of births outside of wedlock and the rising number of dekichattakon (shotgun weddings), which now account for around 25 percent of marriages.

Experts say that those views are also reflected in the limited impact of the sexual revolution in Japan, even after the Equal Employment Opportunity Law came into effect in 1986.

According to Goto, there has been some change, albeit largely superficial. The joshi-tandai two-year women’s colleges — which Goto says were basically “finishing schools” preparing women for a life of domestic chores — have virtually disappeared during the Heisei years and, while male university graduate numbers have stagnated, their female counterparts have continued to climb.

Meanwhile, following a revision to the law in 1997, terminology deemed to be sexually discriminatory was superseded by more politically correct jargon. Even national broadcaster NHK — a great bastion of Japanese conservatism — jumped on board the sex equality bandwagon, rewording the title and opening song of a popular children’s program called “Hataraku Ojisan” (“Working Middle-aged Man”) to include working women as well, Goto says.

“(With the passing of the law), women’s empowerment was much thought about and talked about — not just the sociological aspects, but from a political perspective as well,” Goto says. “Slowly women began to gain social standing but, in reality, little changed.”

Indeed, gender discrimination, especially in the workplace where 30 percent of women suffer sexual harassment, has remained a problem, resulting recently in the #WithYou solidarity movement.

A central reason was the deep-rooted, male-privileged “customs” that preceded it, and a lack of support systems — nurseries and other applicable welfare facilities — that were, and largely still are, woefully insufficient to enable greater female participation in the workplace, Ueno says.

And with few companies adequately equipped to make use of even the most talented females, many women were forced to make do with largely low-paying, part-time work and no real means to break away from their established role in an “ideal” Japanese family, Ueno says.

While in the early Heisei years most women in the workforce were working part time to earn a little extra to supplement a husband’s income, in more recent years a far more serious issue has confronted working women, she says.

“The most significant increase during the Heisei Era was new female graduates and single mothers who work not for extra income but to maintain their own lives and households,” she says.

According to government statistics, 82 percent of Japan’s 1.23 million single mothers are employed, although only 42 percent of them in regular employment. Their average annual earnings total under ¥3.5 million, less than half the national average (¥7.1 million for a household where at least one child is present.)

Many single mothers, however, must work two or three jobs just to earn above the poverty threshold, set by Japan’s welfare ministry at ¥1.2 million per person per annum, Ueno says.

“This is another vestige of the Heisei Era — the ever-widening class gap,” she says in reference to recent OECD figures indicating Japan’s growing poverty rate and widening income gap.

“In the 1970s, Japan ranked next to Sweden as having the smallest income gap among OECD countries,” Ueno says. “In the 2000s, however, Japan came in next to the U.S., which has the world’s biggest income gap. … After the collapse of the bubble economy, the drawn-out recession and neo-liberalist reforms increased that class gap and greatly affected the Japanese family structure. Japan can no longer call itself a middle-class or mass society.”

Other issues affecting women’s role outside the home were based around Japanese society’s strong views on appearances, says Chuo University’s Yamada. For example, a “house husband” is viewed as more than just a curiosity, while leaving children in the care of a third party has long been frowned upon, he says.

Another reason is the stronger emphasis here on “parent-child” relations over those of the “couple” — an issue that is at the heart of the parasite singles phenomenon, Yamada says.

The increasing number of such singles coupled with falling numbers of people looking for long-term relationships have helped instigate alternative forms of “family” and communication during the Heisei Era, says Yamada.

In the 2000s, “uchi no ko” (“our kid”) was used by (often childless) couples or singles to refer to their pet, a phenomenon that led to another popular Yamada-coined phrase, “kazoku petto” (“family pet”).

More virtual means of satisfying hankerings for familial feelings could be found in cat cafes, maid cafes and their female-targeted counterparts, “boys love” cafes — all of which went on to become Asia-wide phenomenon, Yamada says.

Meanwhile, the “rent-a-family” industry has also started to blossom here, finding favor even among the elderly, who are increasingly living alone (27.1 percent of people aged over 65 in Japan were living alone in 2016 compared with 10.7 percent in 1980, government statistics reveal). Day care facilities for Japan’s bludgeoning elderly population also place emphasis on the concept of creating a family environment, assigning chores and activities to reflect that.

Then there is the “digital family” favored by the likes of Akihiko Kondo, which are characterized by a total absence of human communication and have come under some criticism as a result.

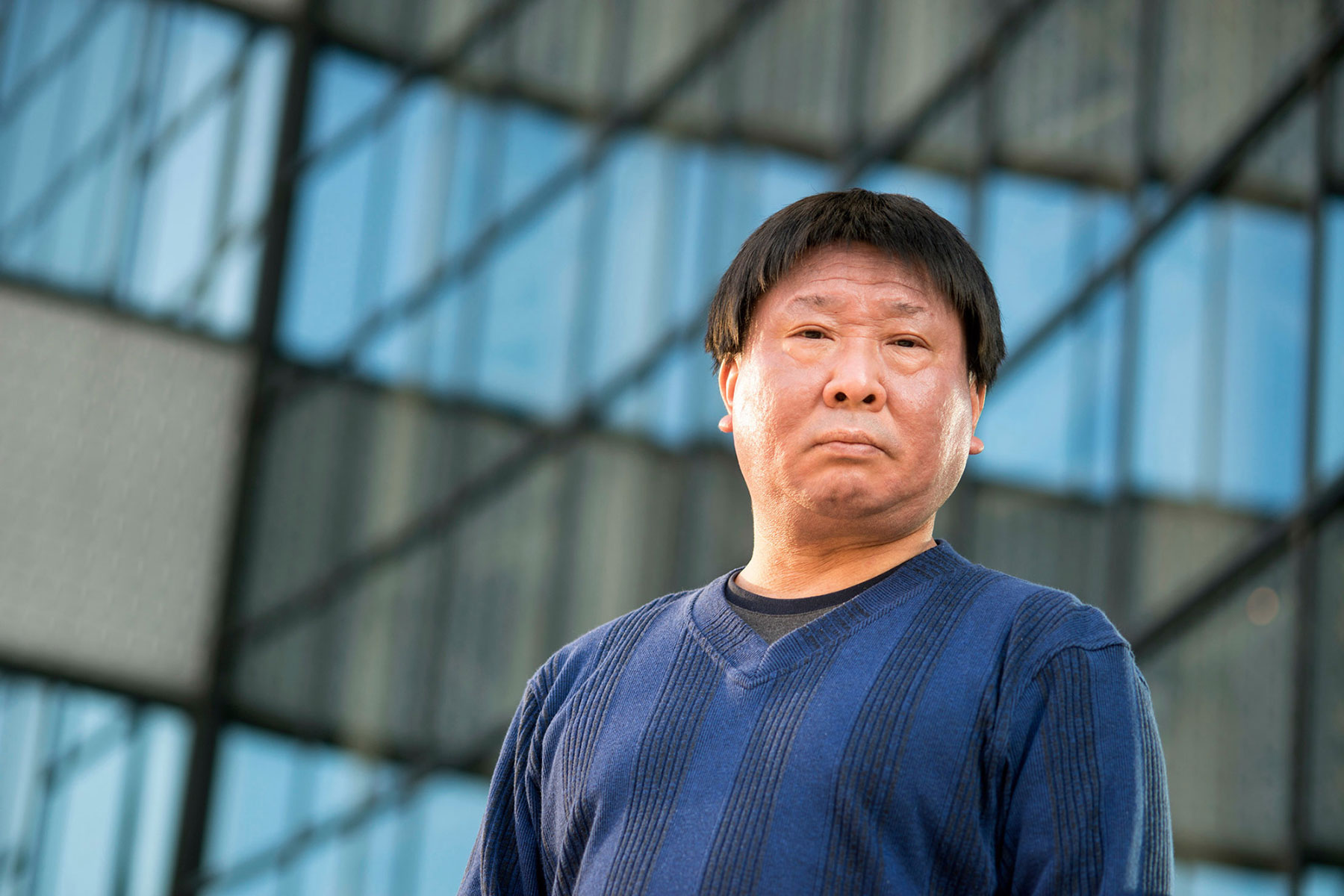

“I can understand the attraction of a life partner who never gets old or dies, but surely that’s an essential part of life and the good and bad experiences that it throws at you along the way,” says Satoshi Tanaka, 45, who has shared, by choice, a marriage-less, and childless, relationship with Sachiko Ushida for over 12 years having met her through the online virtual world Second Life. “I find it difficult to believe this is a picture of the future family.”

Experts agree, with writer Goto saying such virtual families will prove to be nothing more than a fad and even the predominance of single households will fade out naturally.

“That trend might go on for upcoming years but at some point (singles) won’t be able to financially maintain their present levels of living alone,” he says. “We are already seeing an increase in shared homes, and even this may naturally lead to a rise in couples co-habiting and an increase in the birthrate.”

Former University of Tokyo Graduate School sociology professor Chizuko Ueno concurs. “The Heisei Era might have seen the end of modern family,” Ueno says. “However, it does not necessarily mean the end of the family itself.”