SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 8

Communication

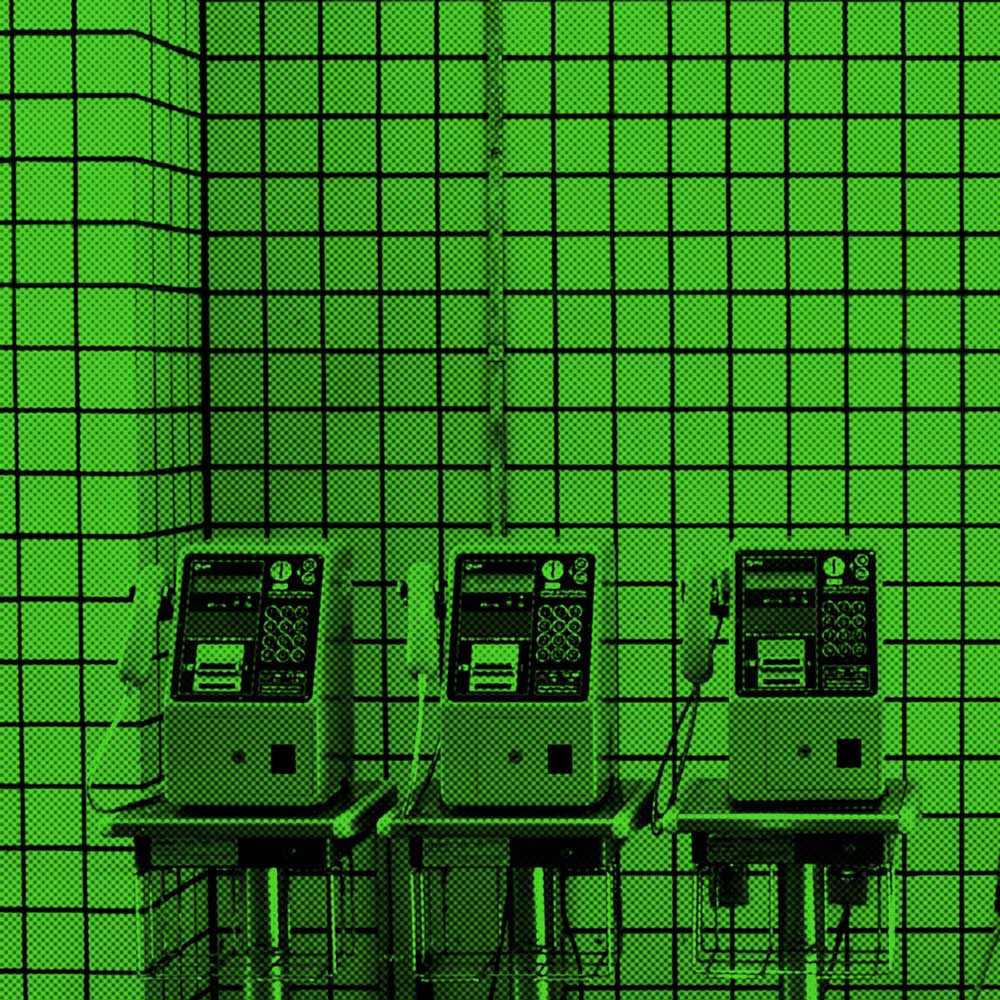

Endangered species: Public pay phones sit in a line in Yokohama in January. | BLOOMBERG

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the eighth installment of a series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades. This installment examines advances that have been made in communication and the impact it has had on society

TIM HORNYAK

Contributing writer

How did one say, “I love you” in 1990s Japan? It could be done in just five digits: 14106. Missing a sweetheart? Try 3341.

Those were the days when combinations of numbers could convey one’s innermost feelings. The must-have gadget of the time was a variety of pager known as the Pocket Bell.

The news earlier this month of the death of pager services in Japan, a full 50 years after they began, made international headlines. In the mid-1980s, however, so-called pokeberu took off and millions of Japanese people from salarymen to schoolgirls were furiously texting each other. This movement marked the birth of texting and mobile communications in Japan.

In the past 30 years, Japan has gone from bubble and bust to global brand and B2B supplier. It has also undergone a communications revolution led by companies such as NTT Docomo, the nation’s largest mobile carrier. Digital technologies such as email, Web 2.0 and smartphones have changed countries around the world, and Japan is no exception. However, Japan initiated and adapted those technologies for its own ends and used them in unique ways. The era beginning in 1989 and known as Heisei, or “peace everywhere,” could just as easily be called “phones everywhere.”

‘Bell friend’ boom

One of the most powerful sparks that lit the communications revolution in Japan occurred in 1985, when the state-owned Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corp. was privatized as Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) amid liberalization of the telecommunications sector. In a reorganization in 1992, NTT Mobile Communications Network, Inc. (now NTT Docomo) was born and took over NTT’s mobile business.

In the mid-1980s, mobile phones were hilariously bulky by today’s standards. However, pokeberu pagers were small, cheap and could be used just about anywhere. Following the device’s launch in 1987, pokeberu were marketed to businesses and spread rapidly over the next 10 years. By 1991, there were about 5.75 million pager subscribers in Japan, of which NTT had some 3.5 million. However, user demographics shifted rapidly. By 1993, nearly 70 percent of new NTT pager subscribers were individuals instead of companies.

Paging became such an integral part of daily life that the technology influenced relationships. One television show of the day was “Pokeberu ga Naranakute” (“My Pager Doesn’t Ring”) and it featured a song of the same name by Mari Kunitake with a chorus that ran along the lines of, “My pager doesn’t ring and my love is stalled.”

Schoolgirls in particular began referring to their berutomo (bell friends). Some berutomo would never even meet in person and only knew each other’s pager numbers, not their names. It was an embryonic form of social media. Users would use the keypads on public phones to text each other strings of numbers every day. “What are you doing?” was 724106, “work” was 4510 and “good night” was 0833.

“I began to use a pager when I was 16. At first, I used it for asking my friends to call me because we needed to call home phones to talk,” says Yoshimi Yoshida, a pharmacist living in Tokyo. “We especially needed it for boyfriends because I went to a girls’ high school. If boys would call my house, my parents always asked me about them, which was so annoying. We also used pagers to meet up with friends outside. There were always lines at public phones to send pager messages.”

Byzantine by today’s standards, berutomo texting fostered arm’s length friendships that appealed in another way.

“Anxiety regarding direct communication among some Japanese youth was such that they avoided calling on the phone and instead preferred text messaging,” Kenichi Ishii of the University of Tsukuba noted in a 2006 Journal of Communication study. “Young people, especially teenaged girls, found that communication needs were better served by text messaging through mobile media, and they readily adopted it.”

Japan’s pager craze peaked in 1996 at 10.6 million subscribers and then quickly fizzled as mobile phone use exploded. NTT had as many as 6.5 million Pocket Bell users and continued pager services under the brand QUICKCAST, only ending them in 2007. Japan, however, loves its zombie technologies. Just as telegrams are still available here — NTT East’s D-Mail service will still dispatch telegrams anywhere in Japan, even to remote islands — pagers lived on way past their use-by date. Tokyo Telemessage is a Shimbashi-based company that offered pager services to doctors, first responders and local governments, but subscribers have fallen below 1,500. The firm will pull the plug on the service in September 2019 to concentrate on offering emergency radios that use the old 280 MHz pager frequency.

“Pagers offered text-based communications and reliable reception requiring minimal base stations,” Tokyo Telemessage President Hidetoshi Seino says. “The old models could hold a battery charge for a month, which is very useful during natural disasters when electricity is cut off.”

Birth of mobile phones

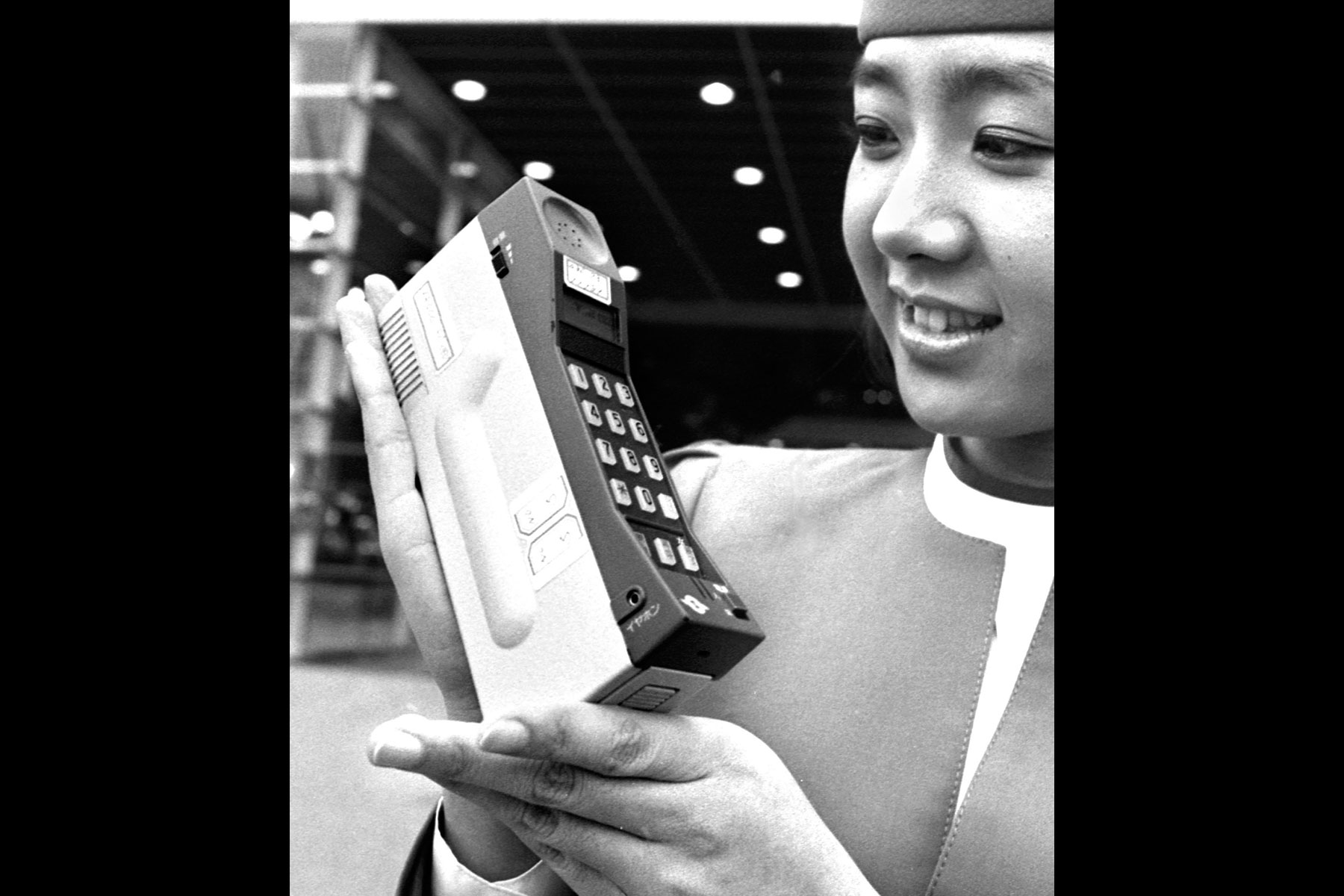

Heisei communications can broadly be split into three 10-year periods, with the first marked by pagers and mobile phones (keitai), the second by internet and camera phones, and the third by smartphones and chat apps. Japan’s first mobile phones included NTT’s “shoulder phone” from 1985, a 3-kilogram behemoth consisting of a shoulder-slung transmitter and attached handset. The TZ-802 model that came out in 1987 dispensed with the bulky transmitter but was still as big as a brick and weighed 900 grams.

Things improved in the early 1990s, with the 1991 Mova N weighing 280 grams and featuring a monochrome 30- by 50-millimeter display as well as the amazing ability to store up to 20 phone numbers. If that wasn’t convincing enough for prospective buyers, Mova phones were promoted by Hollywood hotshot Bruce Willis.

An early technology that helped kick-start the mobile craze was the personal handy-phone system (PHS). Offering bare bones cellular services, low charges and generally better sound quality than regular mobile phones, PHS proved popular among young Japanese. NTT launched a PHS service in 1995 and saw subscribers peak at 2.12 million two years later; it pulled the plug in 2008. The dominant market player was Willcom, known for its DDI-Pocket brand. Absorbed by SoftBank’s budget cellular provider Ymobile following a 2010 bankruptcy, its service still exists, but not for long. Ymobile will shut down PHS services in July 2020, signaling the end of the format in Japan.

Even before it could gain any real traction, however, PHS was eclipsed by the more functional keitai being offered by NTT Docomo, J-Phone and KDDI. In April 1994, industry deregulation allowed companies to sell mobile phones instead of simply renting them, touching off explosive growth in mobile subscribers. Intense competition fueled rapid innovation. In 1997, J-Phone unveiled the Pioneer DP-211SW, which had a face with no buttons, only a liquid crystal touch screen. Not only could it show kanji, something most phones of the time could not do, it could display emoji, the smiley faces and other icons that are now part of the internet’s lingua franca. The promotional images for the DP-211SW showed off a tiny spouting whale. This humble graphic was the very first emoji to appear on a phone screen, according to author Matt Alt’s “The Secret Lives of Emoji: How Emoticons Conquered the World.”

I-mode revolution

1997 was also the year that NTT Docomo began developing a new feature that would put mobile phone evolution into overdrive and into nearly everyone’s pocket: internet connectivity. Based on a proposal by McKinsey & Co. consultants, the concept was spearheaded by Docomo General Manager Keiichi Enoki and was revolutionary in more ways than one. At the time Docomo was mainly targeting younger businessmen with its phones and had introduced DoPa, a packet-switched network communications service in which cellphones could act as modems for devices such as electronic dictionaries. Enoki, however, had observed his children using pagers and PHS phones with ease, and reasoned that phones that could send email and connect to the internet could be a hit with the general public, including younger users. Takeshi Natsuno, an entrepreneur hired by Docomo to develop the service, conceived of mobile phones as a new medium for distributing data and advertising, something you could use to make dinner reservations and buy airline tickets.

What would this revolutionary new service be called? Docomo toyed with names such as lamp, Monet, MOGI (mobile gear interactive), Kokomo, Pitto-kun and Mobaster. Developers Mari Matsunaga and Shigetaka Kurita finally settled on “i-mode,” with the “i” standing for “internet,” “interactive,” “information” and, of course, the first-person pronoun. A few months later, Apple introduced its first “i”-prefixed product, iMac, and “i” became a symbol for cutting edge technology for more than 10 years.

“I-mode was an innovation made by people with different backgrounds,” says Matsunaga, once known as the “mother of i-mode” and now a board member at Seiko Epson. “I called the team ‘Seven Samurai’ in my book ‘I-mode: An Analogue Account of the Mobile Internet.’ Such diversity led to the realization of such technology. I’m proud that i-mode was a forerunner of internet technology in the world.”

When the service launched in February 1999, it marked the first time mobile phone users could browse pages and send email. The first i-mode phone, Fujitsu’s F501i HYPER, had a circular “i” button above the keypad, like a portal to a new world. Another attraction of i-mode phones was the ability to send smiley faces and about 200 other emoji that were compiled by Kurita, now known as the “father of emoji.”

“I knew from my experience with pagers that exchanging short messages over digital devices creates discrepancies in communication,” says Kurita, today a director at Dwango Co., operator of video-streaming service Nico Nico Douga. “I imagined what it would be like if you could add emotion and nuance to messages as well as decorations to express one’s individuality. Through messaging, communications would be fun.”

Fueled by public zeal for web browsing and emoji messaging, and helped by promotions featuring actress Ryoko Hirosue, i-mode saw stratospheric growth and, by mid-March 2000, sales topped 5 million units. In a few years Docomo had more than 30 million internet customers, growing to the size of America Online but five times quicker. It went from nearly zero to more than $30 billion in revenue as the economy was foundering.

By December 2000, about half the Japanese population was using mobile phones, of which 26.4 million were internet-capable. Matsunaga and Docomo President Keiji Tachikawa were feted by publications such as Business Week and Nikkei Woman. KDDI and J-Phone rolled out their own online services and the mobile internet was a resounding success. Indeed, its effects are still being felt nearly two decades later.

“The biggest change in communication during the Heisei Era has been ‘mobile digitalization,'” says Natsuno, now a guest professor at Keio University. “I-mode e-mail evolved from just text base to a richer format such as text with pictures, animations and html mail. Many people who didn’t even have email accounts on their PCs started to have mobile email accounts that can communicate with PC email as well. In this sense, we can say the internet revolution in Japan started from mobiles.”

Mobile internet takes root

Docomo tried to bring i-mode overseas, launching it first in Germany in 2002 and then other countries, but ultimately it proved to be another highly evolved “Galapagos” technology that would only thrive in Japan’s unique ecosystem. Emoji, however, were adopted as Unicode standards and incorporated in iOS and Android phones, making them part of communication around the world.

Another invention popularized in Japan that dodged the Galapagos bullet had an even greater impact: the camera phone. In 1999, Kyocera released the Visual Phone VP-210, boasting a built-in camera and a 2-inch color LCD screen. It’s now regarded as the world’s first handheld wireless color videophone.

The following year, South Korea’s Samsung offered the SCH-V200, which also had a camera but images were only accessible from a PC and not the phone itself. Five months later, Sharp produced the J-SH04, which is often regarded as the first true camera phone. Launched by J-Phone in November 2000, the J-SH04 boasted a 0.11-megapixel camera and the ability to send photos electronically via the carrier’s “sha-mēru” (photo mail) service. So-called sha-me photos became wildly popular in Japan and two years later phones such as the Sanyo SCP-5300 brought the fad to the West through U.S. telecom Sprint. The selfie was born.

“Due to the spread of the internet, a paradigm shift occurred in communication in that distance and time became irrelevant,” says Ichiro Michikoshi, an executive analyst at Tokyo-based IT research firm BCN Inc. “The greatest success of the Heisei Era is sha-mail. The J-SH04 triggered the connection between the mobile terminal and the camera, leading to the current smartphone. It showed the way for a new image of communication in the digital age.”

In the early 2000s, Japanese cellphones evolved rapidly, with Japan-only innovations such as FOMA, the world’s first 3G service, and 1Seg, a digital TV tuner, launched by Docomo in 2001 and 2006, respectively. Japanese consumers were happy with their increasingly sophisticated flip phones, which were generally superior to anything in the West, until Apple launched the iPhone in 2007. The Cupertino giant began its dominance of the domestic mobile market with the launch of the iPhone 3GS in 2009. But Japan was fully primed for the smartphone era.

“Thanks to the development of ‘Galapagos’ phones 10 years prior to smartphones, the Japanese community could use this new way of digital communication naturally, easily and frequently,” Natsuno says. “Even with limited capability and speed, internet-enabled phone service enabled many applications and ways of communications both for content providers and consumers. Unfortunately, Japan could not take this great opportunity to dominate the world.”

Getting in Line

Japan may not have capitalized on its pioneering role in mobile communications, but a fresh generation of entrepreneurs was giving Japanese new ways to interact. Mixi, DeNA, Mobage and GREE were building social media and gaming platforms that attracted a massive user base. By 2010, they had more than 50 million users between them, and Japan itself soon became the world’s top spender in terms of app revenue.

GREE, founded in 2004, is usually described as a mobile gaming company, but its CEO — Yoshikazu Tanaka, who was by 2010 one of youngest self-made billionaires in the world — has written about how he launched the service as a way of “creating a new way of communicating and a new community.” Gamers found fellow players and friends on mobile platforms, and sometimes more.

In 2009, one enthusiastic Tokyo gamer even “married” a female character named Nene Anegasaki from the Nintendo DS series “Love Plus.” The wedding, the first of its kind between man and character, was broadcast live on Nico Nico Douga, which had grown to become a new form of mass media along with the gargantuan anonymous online bulletin board 2channel.

For person-to-person communication, however, few made-in-Japan services can compare to the cultural juggernaut that is Line. It was created by engineers at NHN Japan (now Line Corp.), part of South Korea’s NHN Corp. (now Naver), as a response to the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, which devastated communications infrastructure. Released to the public as a free messaging app named Line in June, three months after the temblor, it proved astonishingly popular: in 13 months it had 45 million users, which ballooned to some 205 million by 2015, with annual revenues of $702 million; Line generated the biggest tech initial public offering of 2016, raising $1.1 billion.

“Although Line started off as a messenger, today it is rather a platform offering various services from personal finance to AI home speakers,” a spokesperson from Line Corp. says. “With the Heisei Era coming to an end, Line recognizes new opportunity in voice recognition as the next technology that will impact the ways people communicate in the upcoming era.”

Today, just about everything in Japan, from Shibuya City and AKB48 to Toyota and the Prime Minister’s Office, is on Line. As it diversified into everything from taxis to cryptocurrency, its growth has been fueled by games, ads and sales of digital stickers including now-iconic “Line Friends” characters such as Brown, Cony and Moon. Also known as stamps, the stickers are emotive, funny and three-dimensional: They have backstories and relationships.

“Emoji spread to the world as a means of communication from Japan,” says Shigeyuki Kishida, an executive consultant at Tokyo-based IT research firm InfoCom Research. “It can be said that emoji have evolved into Line stamps.”

As Kishida notes, the evolution of communications technology during the Heisei Era is a movement from group-based to individual-based, voice to data and use in fixed locations to anywhere. The next phase will see countless machines join the immeasurably vast chat room we partake of in our daily lives: Japanese carriers will roll out 5G services in 2020, promising faster broadband speeds and accelerated spread of “internet of things,” AI and other cloud-based services.

“With the acceleration of mobile communications, we will be connecting and controlling every home appliance through mobile terminals,” Michikoshi says. “High-speed communication technologies such as 5G are spreading relatively quickly, and communication environments featuring high capacity and high speed are spreading. Furthermore, with the progress of IoT and AI, the importance of communication will be much higher than before.”