SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 7

Obsession

Colorful capital: Store signs in Tokyo's Akihabara district. | GETTY IMAGES

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the seventh installment of a series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades. This installment examines the rise of otaku culture

ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Staff writer

Katsumi Goto is a self-proclaimed old-school otaku.

Born in the city of Nagoya in 1970, he spent his teenage years devouring popular anime series of the time, including “Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam,” the sequel in the well-known Gundam franchise that first aired in 1985, and “Dirty Pair,” a sci-fi adventure featuring a sexy female duo working as “trouble consultants.”

This was the heyday of the VHS cassette, and Goto would spend his allowance renting anime tapes, many of which were made specifically for release on home video format to meet the period’s surging demand for anime content.

It wasn’t a hobby he could openly share with his classmates, however. This was years before the otaku image underwent a makeover of sorts, thanks to the popularization of the fan culture and its global acceptance as a source of soft power.

“Otaku of our generation were typically way down in the ‘school caste’ system, and girls tended to look at us with disdain,” he says, referring to the invisible hierarchy in the classroom determined by different status symbols. “But a lot of that seems to have changed.”

Dark roots

It would be an understatement to say the concept of otaku — a highly loaded and ambiguous term derived from an honorific for “you” in Japanese — had a rough debut in the nation’s mainstream narrative.

First introduced by essayist Akio Nakamori in 1983 to describe socially inept manga and anime-obsessed nerdy types who were known to address each other in absurdly polite terms, the word gained widespread notoriety in 1989 when a 26-year-old man named Tsutomu Miyazaki was arrested and later sentenced to death for killing and mutilating four girls, aged 4 to 7, and sexually molesting their corpses.

Police searches found thousands of video tapes cluttering the serial killer’s room, including anime and slasher films, leading mass media to dub Miyazaki the “otaku murderer,” a moniker that would tarnish the image of the social demographic for decades to come.

“Prior to Miyazaki, the public image of perpetrators of similar bizarre crimes were often of delinquents and those from complex upbringings,” says Kaichiro Morikawa, associate professor at the School of Global Japanese Studies at Meiji University and an expert on manga, anime, games and related popular culture.

“But talk shows began using the word otaku to describe the outwardly innocuous suspect who appeared to fit the stereotype the phrase conjures, imprinting the idea that these people are would-be criminals,” he says.

Reclaiming the subculture’s damaged reputation would soon begin in earnest, but the image of predominantly male, reclusive social outcasts living in their fantasy worlds embodied by Miyazaki haunts to this day.

“In retrospect, the Heisei Era (1989 to the present day) began with the worst possible introduction for the term otaku and has since been undergoing the process of neutralizing its negative connotations,” Morikawa says.

Shifting commercial market

Goto continued to pursue his passion in high school, vigorously studying past anime releases he missed, such as “Armored Trooper Votoms,” a military sci-fi mecha (robot) anime series that ran in 1983 and which left a profound impact on video games.

While he lived too far away to attend the biannual Comic Market fan convention held in Tokyo, Goto had other means to stay up to date with trends. The late 1970s to the mid-1980s saw a slew of influential magazines launched, including Out (1977), Animage (1978), Animec (1978) and Newtype (1985), supplying dedicated fans of anime and its peripheral subculture a source of information on the rapidly growing scene and a sense of connection with fellow enthusiasts.

Goto, a 48-year-old graphic designer with a ponytail, recalls scribbling manga characters he invented in notebooks during class and playing the American fantasy tabletop role-playing game “Dungeons & Dragons,” whose translated version landed in Japan in 1985. The blockbuster “Dragon Quest” video game franchise also released its first installment in 1986 for Nintendo Co.’s Family Computer console, transfixing Goto and his friends with its world of monsters and wizardry.

The Showa Era (1926-89) wore off and Japan’s economic bubble burst, but the historical events at the turn of the 1990s had little to do with Goto, who around that time was studying to get into an art college in Nagoya.

“It’s customary for otaku to buy three copies of the same thing: one for your collection, one to give to an acquaintance and one for your own entertainment,” Goto says.

“We are good customers, and we didn’t let our spending habits be affected by the bubble’s popping or the subsequent economic stagnation,” he says, outlining perhaps one reason why anime and other related contents gradually shifted its target from young children to a broader age group.

There was another sweeping change rewriting consumer demographics: fewer children. The nation’s total fertility rate, which measures the number of children a woman is expected to have over a lifetime, hovered near 2.0 around the time Goto was born. But by 1989 it had sunk to 1.57 and would continue to fall until it hit a record low 1.26 in 2005.

With the number of children shrinking, popular entertainment naturally began targeting the otaku population that didn’t hesitate to open their wallets for material many considered juvenile.

‘Convenient narratives’

The early ’90s saw the bishojo magical girl concept really take off, epitomized by “Sailor Moon,” a manga and anime series that began airing on television in 1992. Along with Akira Toriyama’s “Dragon Ball,” the title morphed into one of the nation’s biggest pop culture exports.

Goto followed the “Sailor Moon” broadcasts that lasted until 1997, finding a favorite in Rei Hino, a girl with fiery but traditional traits better known as Sailor Mars.

However, he says, nothing eclipsed the impact of “Neon Genesis Evangelion,” anime studio Gainax and director Hideaki Anno’s 1995 series credited for single-handedly changing how anime was made and consumed by the public in the new age of multimedia.

The 26-part series originally ran from 1995 to 1996. Goto recalls he was in his final year of college when the first episode played in October.

“I knew something amazing was happening,” he says, still regretting having missed the final episode that ran the following March.

The story’s premise is simple, revolving around giant bio-machines called Evangelion and their 14-year-old pilots. But Gainax and Anno introduced highly developed narratives with an abundance of religious, psychological and philosophical themes while incorporating an emotional and spiritual depth to its characters.

From being a cult phenomenon with a small fan base, Evangelion gradually became a mainstream success in Japan as word-of-mouth and reruns of the original attracted new viewers.

In his book, “Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals,” cultural critic Hiroki Azuma says the Evangelion boom was unique in how the production company, Gainax, produced spinoffs and related merchandise with concepts far removed from the original, including mahjong games, erotic telephone cards featuring its characters and even simulation games where players nurture the heroine, Rei Ayanami.

“This thing that Gainax was offering … was an aggregate of information without a narrative, into which all viewers could empathize of their own accord and each could read up convenient narratives,” he says.

The success of Evangelion and the big money it was raking in convinced shop owners of otaku-related merchandise scattered across Tokyo and elsewhere to relocate in Akihabara, which was fast becoming a center for the evolving culture.

Akihabara’s new status

The busy commercial district in central Tokyo was primarily an electronics hub until the late 1980s, drawing weekend family shoppers looking for new refrigerators and washing machines.

However, as suburban electronic appliances stores began to sprout in the 1990s, Akihabara’s raison d’etre was put to question, prompting it to shift its focus on specializing in still-emerging personal computers.

That, in turn, began attracting young, male computer geeks with strong affinities toward typical otaku hobbies including anime, figures and garage kits.

1994 saw the release of Sony Corp.’s PlayStation console, while Microsoft Corp.’s epoch-making operating system, Windows 95, went on sale the following year, ushering in a new generation of computer users and a wave of new games, including numerous anime-influenced dating simulation games and erotic adult titles.

Goto, who by then was working for a Tokyo-based advertisement firm, recalls this was around the time Akihabara’s makeover as an otaku mecca became visibly noticeable, with an explosion of stores catering to their desires.

Ads for anime videos and games were popping up everywhere, and while outlets still offered home appliances, Akihabara had begun to assume an identity as an otaku safe-haven.

By the turn of the millennium, maid cafes began sprouting, where girls in cosplay outfits serve tea and light meals to tired shoppers. Media played up these joints, introducing them as a favorite otaku haunt and prompting curious tourists to flock to the area. The social stigma attached to otaku appeared to slowly dissipate as the motifs of the subculture began to permeate Japanese society and beyond.

Perhaps most influential in changing attitudes was 2004s “Densha Otoko,” a sentimental love story of an awkward nerd who, supported by an online community, breaks out of his shell to win the heart of a fashionable working woman.

Supposedly based on a true story from a thread on 2channel, then-Japan’s largest internet bulletin board, the phenomenal success of the book, film, television series and manga based on the story cast otaku in a kinder, more humane spotlight, although it also implied that the only way for them to be involved in a romantic relationship was by abandoning their childish hobbies and dressing better.

“Densha Otoko” coincided with the “Akiba boom” of the mid-2000s when the district became widely featured in media as a center of a thriving subculture. Akihabara’s newfound status also provided fertile ground for the return of another otaku subgenre: idol culture.

Idol worship

Tama Himeno, a 25-year-old “underground idol” and writer, says the nation’s obsession with idols can trace its modern roots to the economically booming 1980s, when star singers such as Seiko Matsuda, Akina Nakamori and Kyoko Koizumi drew devoted male fans.

The decade also saw the debut of the first “mass idol” group, Onyanko Club. Produced by lyricist and television writer Yasushi Akimoto, the group, consisting of 50 plus members, morphed into a media sensation during the relatively short course of its life.

However, the 1990s saw idol culture sidelined by the rise of J-pop acts, including singers and groups produced by hit-maker Tetsuya Komuro and top-charting bands such as Mr. Children. Mainstream idol music went underground, with performers moving to more private venues to cultivate smaller but dedicated fan bases.

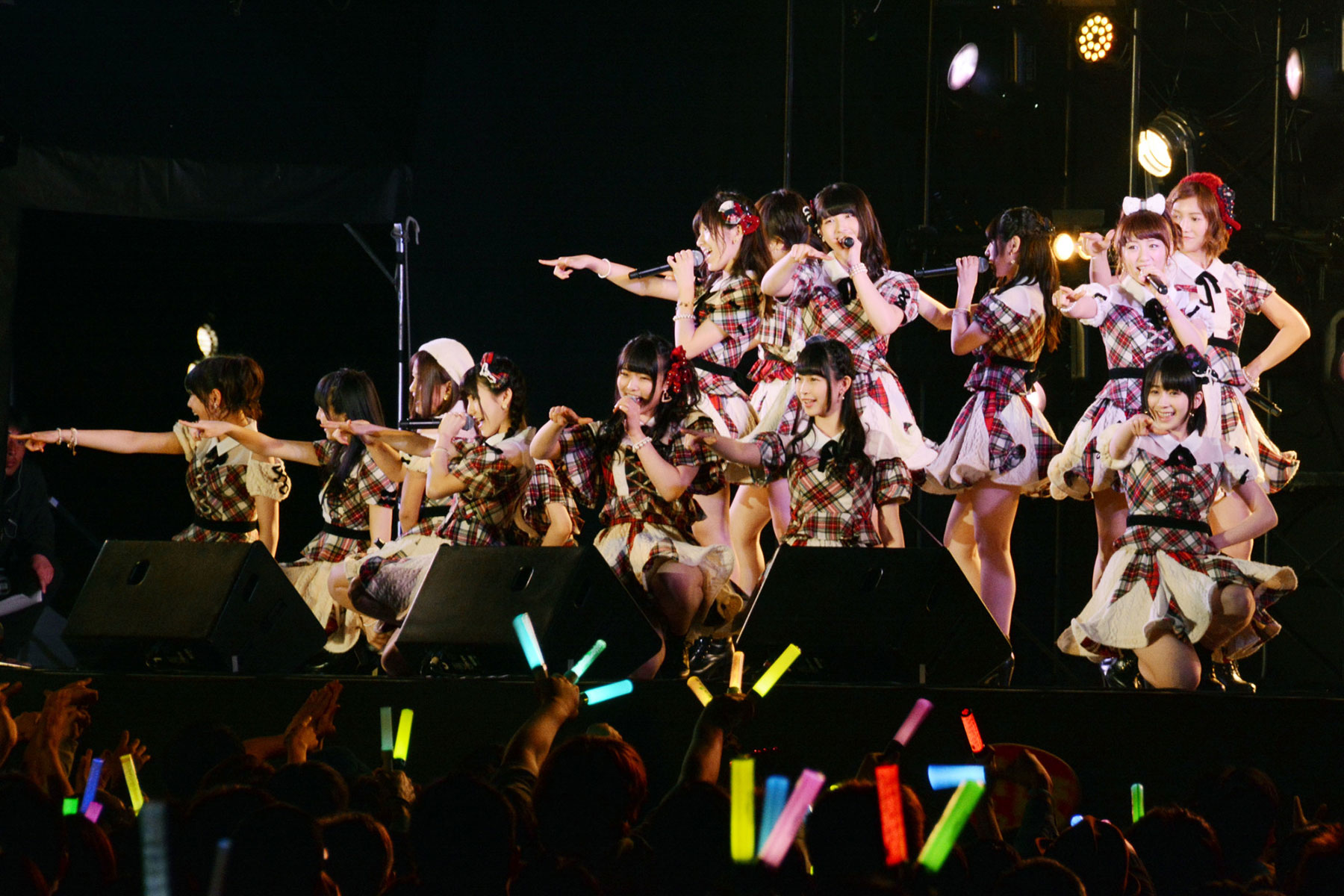

The trend began changing in the late 1990s with the debut of Morning Musume, an all-female idol group produced by rock singer Tsunku that went on to release million-selling singles. What made the culture the dominant scene of the 2000s, however, was AKB48 and the return of Akimoto as the mastermind behind the biggest selling all-girl group franchise in Japanese history and an international phenomenon with numerous local affiliations and commercial tie-ups.

Only seven guests attended the group’s now-legendary 2005 debut performance in its namesake AKB48 theater in Akihabara, but Akimoto was betting on that intimate setting to pay off.

He took cues from how indie idols were connecting to fans in the ’90s. What he aimed for was producing “incomplete” or “unfinished” amateurish idols that fans can meet and nurture as they improve as entertainers.

Himeno says the handshake greeting events the group and its sister groups host is one example of the carefully maintained illusion of closeness Akimoto built — albeit with criticism of ruthless monetization and sexual undertones — where fans who buy CDs and merchandise can queue up to meet their favorite members. These meet-and-greet events also became an unexpected scene of an attack on two group members in 2014 by a man wielding a portable saw.

In 2009, Akimoto orchestrated the first AKB “election,” where fans purchasing AKB CDs are given tickets to vote for their favorite girls. The results were then broadcast on television from massive arenas, creating a faux sense of suspense as the rankings were announced.

This was the same year Himeno, then 16, made her debut as a so-called underground idol. The word has no concrete etymology, but is purportedly derived from how amateur idols often performed in underground live houses for small crowds of fans known for occasionally launching into impromptu singing-and-dancing tirades called otagei.

“The term ‘underground idol’ had a derogatory tone back then, and our audiences were much more otaku-esque compared to recent years when the subculture has been drawing new fans,” she says.

“Think of the ‘Densha Otoko’-type natural-born otaku who were into anime and anime voice actresses and carried excessive baggage around — those were our fan-base.”

The scene has since become a hodgepodge of countless idols, both major and minor, but Himeno feels the peak has passed, and that the idol boom that began in the 2000s may soon give way to something else.

She herself plans to retire from stage. Himeno has booked an 800-capacity hall on April 30 for her last concert, which, inadvertently, is the day Emperor Akihito is expected to abdicate, bringing an end to the Heisei Era.

Global expansion

If the idol boom can be considered a highly marketable subgenre of otaku culture, the central platform that fuels the grass-roots creativity of the scene may be the Comic Market fan convention of dojin (fan-produced) art held twice a year in Tokyo.

Inaugurated in 1975, Comiket, as it is also known, has grown to become the world’s largest fan convention. The most recent three-day event that lasted from Aug. 10 to 12 drew 530,000 attendees including cosplayers bearing the summer heat as they made their way between thousands of booths selling fan art ranging from manga, anime, music and countless other merchandise.

It was the early Comiket events that spawned the cosplay, or “costume play,” trend in Japan, when dojinshi circle members started dressing up as favorite manga and anime characters in order to attract attention to their products. The phenomenon has since gone global, with cosplay-themed events being held regularly in numerous countries.

Kazutaka Sato has been helping run the not-for-profit event for three decades, and credits the event’s continuity for sending out talent into the world and maintaining a place amateurs and professionals can freely showcase their creativity without hierarchical constraints.

That feeling, and the global reach of the culture he witnessed at the Japan Expo in Paris where he saw crowds of French otaku, prompted Sato and two other co-founders to launch the International Otaku Expo Foundation in 2015 as a means to bridge the many otaku-themed conventions held around the world. The organization now includes 118 events from 44 nations, Sato says.

“These events are like schools that educate future talent,” he says. “Comiket has been thriving since way before the Heisei Era and that perseverance is key ton creating a culture. It takes time.”

Loss of identity

Goto, who is single, lives within walking distance of Akihabara and is occasionally interviewed to explain the allure of otaku culture and its mecca. He watches around 20 episodes of newly released anime series a week — “too few for an anime otaku,” he says — and knows where to find shops down narrow alleys that sell rare board games and anime goods.

He seems somewhat confounded, however, by the growing popularity of the subculture and how it seems to be infiltrated by “regular” people.

“For otaku like myself who has been part of the scene for decades, it feels like they are stepping into our sanctuary,” he says.

“It’s been our status, or identity, to be knowledgeable on things that the popular kids in class didn’t know or care about,” he says half jokingly. “What are we to do if they also became otaku?”