SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 6

Imagination

Flying high: A Pikachu balloon floats above the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York in November 2016. | AP

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the sixth installment of a series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades. This installment follows the evolution of anime and manga as they go global

ROLAND KELTS

Contributing writer

The Heisei Era commenced after two gods fell in rapid succession. The first, Emperor Hirohito, was no longer officially a god, having repudiated his quasi-divine status under the terms of Japan’s surrender in World War II, but he remained god-like in stature. His January death in 1989 at age 87 signaled the end of a Showa past both turbulent and glorious. It drew global attention from the world’s leaders and media, but had been widely anticipated in Japan.

The other fell just one month later, in February, and his death shocked the nation. Osamu Tezuka, the beloved “god of manga,” died of stomach cancer at the age of 60. News of his declining health had been kept secret, as was then customary in Japan. Tezuka was a prolific workaholic and omnipresent television personality. He was also a licensed physician. Almost no one expected his sudden passing.

The two deaths would augur a new life for Japan’s twin pop culture media: manga and anime. Both would find global audiences in the Heisei years that were previously unimaginable, resulting mostly from the intensifying appeal of the kind of Japanese creativity and innovation that Tezuka had pioneered, but also from the increasingly cheap and easy access to Japan’s cultural products made possible by rapid advances in technology.

Young people in Japan wept openly at the news of Tezuka’s death in early 1989. Career retrospectives and tributes dominated the airwaves. Nearly everyone under the age of 50 at the time had grown up with his stories and imagery, and even those who did not count themselves fans of manga or anime were likely to recognize the theme song of his hit show, “Tetsuwan Atomu” (“Astro Boy”).

Author and translator Frederik L. Schodt, a friend and interpreter of Tezuka’s, compares Japanese reactions to his death to the despair following John Lennon’s 1981 murder. While few newspapers outside of Japan ran news of Tezuka’s passing, inside the country, Schodt recalls, “my friends were all devastated, absolutely wrecked.”

Tezuka arguably created and mastered the template for modern manga and anime: episodic long-form storytelling structures; cinematic, multi-panel visuals; and distinct genre categories such as shōjo (girl’s stories) and mecha(robot epics).

However, the reputation and legacy of his work, and his impact on other Japanese artists, rose globally only after his death, especially in Western, English-speaking markets. During the 30-year Heisei Era, a perfect storm of communicative technologies, diversifying markets and fatigue over the dominant popular cultures of the 20th century converged to transform manga and anime into the face of Japan as it transitioned into the 21st.

Novelist Haruki Murakami once told me that when he lived in Europe and visited the U.S. in the 1980s, he was chagrined to learn that Japan’s image in the West was reduced to automobiles, electronics and exorbitantly priced real estate. Prior to the Heisei Era, Japan’s cultural output barely registered.

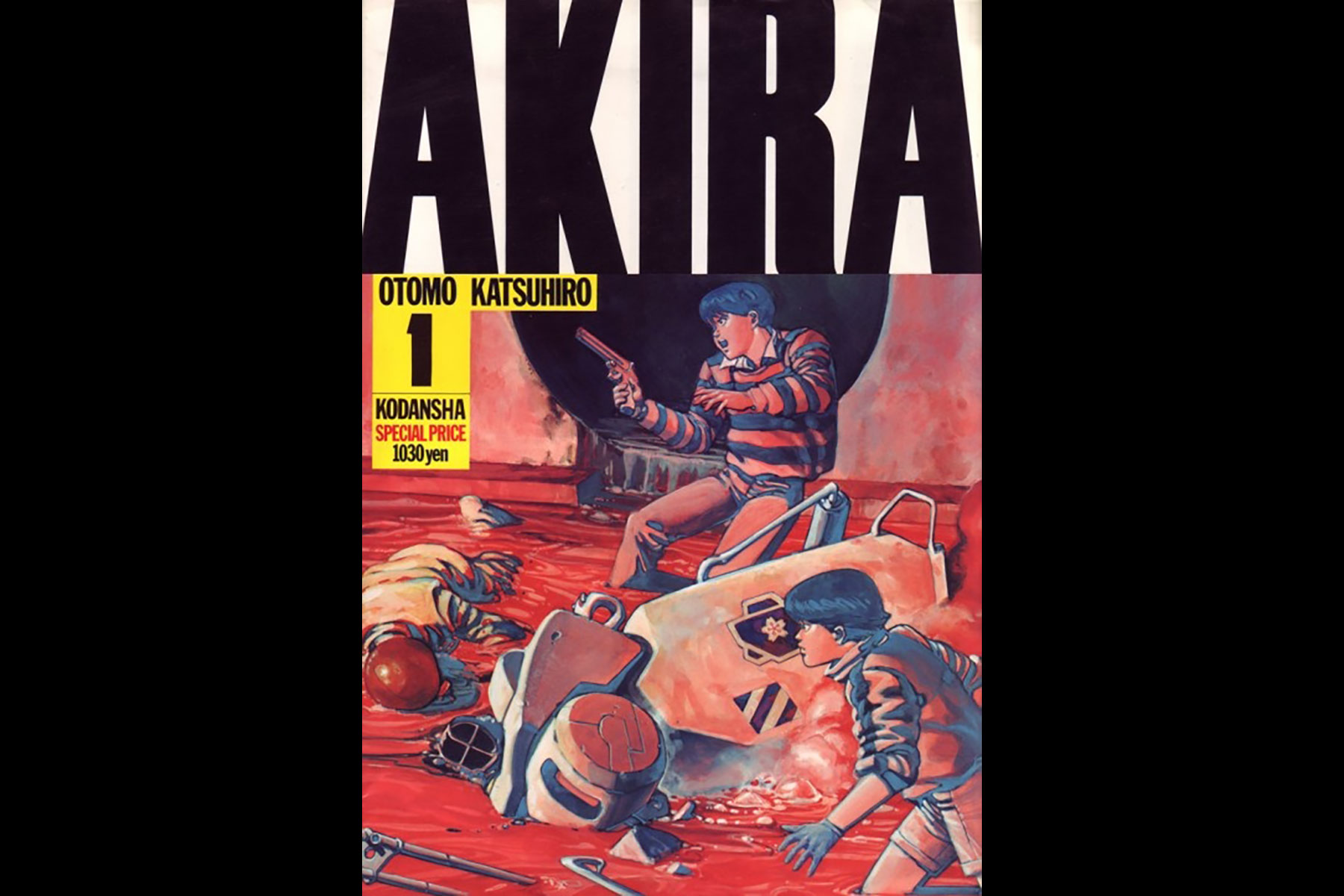

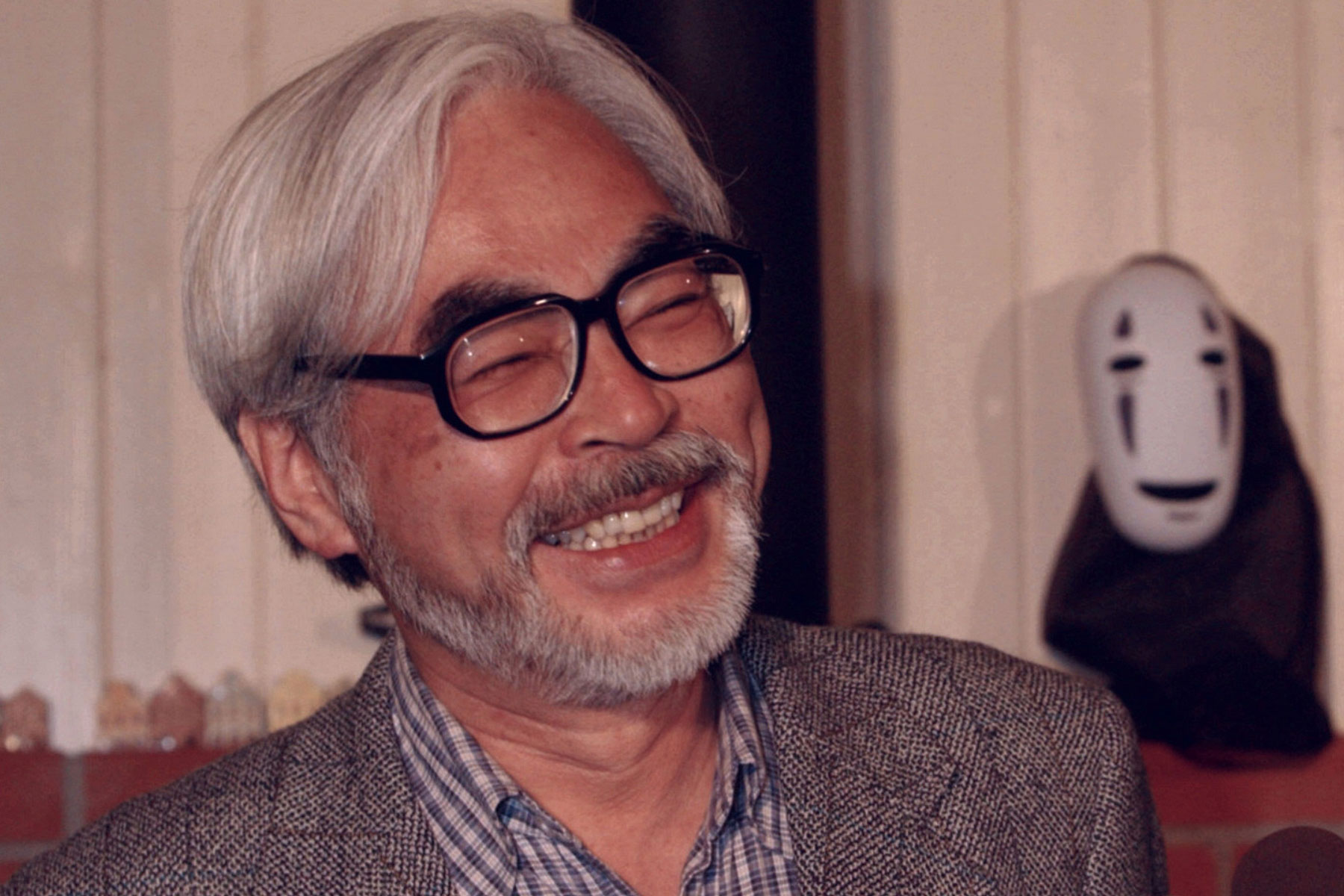

Today, the late ’80s are seen as a golden age of anime and manga by older generations of critics and fans. In the 1970s and early ’80s, limited cult followings abroad had been drawn to television adaptations of Tezuka’s “Astro Boy,” Leiji Matsumoto’s “Star Blazers” (also known as “Space Battleship Yamato”), and Tatsunoko Production’s “Speed Racer” (“Mach Go Go Go”), “Battle of the Planets” (“Science Ninja Team Gatchaman”) and “Robotech” (“The Super Dimension Fortress Macross”). But 1988 alone saw the releases of Katsuhiro Otomo’s “Akira” (based on his own ongoing manga series of the same name, begun in 1982), and Studio Ghibli’s double-feature of Hayao Miyazaki’s “My Neighbor Totoro” and the late Isao Takahata’s “Grave of the Fireflies.”

“Akira,” in particular, was a seminal title in establishing anime’s credentials among film critics, academics and students outside of Japan. Literary scholar Susan Napier, author of “Anime from Akira to Howl’s Moving Castle” and the just published, “Miyazakiworld,” was teaching Japanese literature in Texas in 1989. A student handed her a copy of Otomo’s original manga and she was transfixed. Later that year, she saw the British premiere of the anime feature film, also directed by Otomo, at a cinema in London’s Leicester Square. It changed her career, adding anime to her scholarship expertise.

“I walked out of the theater completely blown away,” Napier says. “I knew that it was a cartoon like nothing that I had ever seen before — visceral, intense, heady and grotesque. I almost had to hide under my seat during the last 20 minutes.”

“Akira” had an equally transformative effect on younger North American audiences, largely through midnight screenings on university campuses, one of which I attended as a student. American college kids toting six-packs and other substances were primed to either laugh at cartoons or be soothed by Disney-style morality tales. But they were struck numb by “Akira,” stunned by its violence, hard-edged graphics, and tableaux of urban anomie and apocalypse.

The impact of Studio Ghibli’s “Grave of the Fireflies” also marked a turning point for anime’s critical reception outside of Japan. While Miyazaki’s “Totoro” would become the go-to movie for parents seeking to mesmerize their children with animation that stimulated rather than assaulted their imaginations, it was Takahata’s deftly paced account of two orphaned siblings in the waning days of World War II that drew the attention of mainstream movie buffs and historians. Esteemed U.S. critic Roger Ebert hailed it as “an emotional experience so powerful that it forces a rethinking of animation,” and “one of the greatest war films ever made.”

Still, these now-consecrated masterworks were neither widely seen nor embraced outside of Japan until the 1990s. And despite the growing critical and academic recognition, anime and manga would not make serious commercial headway in Western markets until two blockbuster titles were licensed abroad: Akira Toriyama’s “Dragon Ball” in the early ’90s, and Satoshi Tajiri and Ken Sugimori’s “Pokemon” in the decade’s latter years. Those two franchises alone remain signature global icons of Japan’s anime and manga industries, a dynamic Heisei Era duo.

Neither title achieved international success solely through raw promotion or advertising. The success story of anime and manga was primarily driven by voracious demand — and the emergent global technologies that could satisfy fan appetites.

To some extent, and in some markets, the groundwork had been laid years earlier. Entrepreneur Seiji Horibuchi, who had been drawn to the San Francisco Bay Area’s bohemian vibe in the ’70s, established Viz Media in California in 1986, roping together parent companies Shueisha Inc., Shogakukan Inc. and Shogakukan-Shueisha Productions, Co., Ltd. Viz was the first manga beachhead in North America and released its three debut titles in 1987, including “The Legend of Kamui.” Initial sales were good but short-lived, driven by specialty collectors of black-and-white comics.

“I thought I had struck gold,” Horibuchi says. “But it didn’t last. Black-and-white comics became less rare and the collectors faded away.”

Horibuchi got creative, switching to anime video releases and publishing manga in longer, standalone (tankōbon) format to appeal to the burgeoning interest in graphic novels. Even so, it would be a decade before Viz saw its first commercial breakthroughs, aided by distribution deals with U.S. bookstore chains Barnes & Noble and Borders, and the broad-based appeal of titles such as Rumiko Takahashi’s “Ranma ½” and the “Pokemon” manga.

“There were a few successful translated manga in the American comics market as early as the late ’80s,” says Jason Thompson, a former senior editor at Viz and author of “Manga: The Complete Guide.” “‘Titles like ‘Lone Wolf and Cub,’ ‘Akira’ and ‘Ghost in the Shell.’ But these were eventually dwarfed by the success of more kid-oriented titles like ‘Dragon Ball/Dragon Ball Z’ in 1998, the American ‘Shonen Jump’ in 2003 and the entire early 2000s TokyoPop lineup, especially ‘Sailor Moon.'”

In the overseas markets of the late 20th century, manga targeting younger readers proved the safest bet.

“Viz’s 1999 ‘Pokemon’ comics by Toshihiro Ono sold incredibly well in a distribution deal with Toys R Us stores,” Thompson says. “They became the first manga to sell over 1 million copies in the U.S.”

Together with U.S. giant Marvel’s “Akira” releases, and independent publishers such as First Comics and Dark Horse Comics, Viz had begun to raise an awareness of the artistic symbiosis between manga and anime, first among a dedicated subculture of comics and science-fiction fans, and eventually radiating outward to a much larger fan base of young people.

At the dawn of the ’90s, Japan’s economic bubble collapsed just as manga and anime began their ascent in the rest of the world.

Demand drove growth. An almost comical example is the story of the international dissemination of “Dragon Ball,” the first manga blockbuster series to be officially licensed outside of Japan. On the front lines were two publishing professionals in two distant cities — and a centimeter-thick stack of faxes.

In 1991, Tuttle-Mori Agency Director Chigusa Ogino was brokering deals for foreign-language murder mysteries in Japan when a request came from publisher Shueisha Inc., whose building is a short walk from Tuttle’s Tokyo offices. Shueisha’s staff wanted Ogino to decipher a huge pile of English-language faxes that had arrived over a period of weeks, all written by an editor named Montse Samon from Spanish publisher Planeta DeAgostini and issued from Barcelona.

Planeta had been doing well selling full-color American superhero comics, but Samon was fascinated by the typical Japanese manga format: thick books, episodic stories, smaller-sized pages and kinetic multi-panel visuals, often exquisitely inked in black-and-white. A local television station in Catalonia had a surprise hit with its nascent broadcasts of the “Dragon Ball” anime series. Samon could neither write nor speak Japanese, so she started by sending a photocopy of the “Dragon Ball” tankobon cover to the Japanese Consulate in Barcelona, with a note asking for help and guidance.

“I just can’t imagine the faces of the people at the consulate,” Samon says. “They must’ve wondered what was going on.”

But Samon got what she wanted: The consulate sent her a fax number for Shueisha — whose name she couldn’t pronounce.

Samon first sent faxes weekly, then daily, slipping the same request into the machine and typing in the Tokyo number before leaving her office. She estimates that she may have sent 100 or more before finally receiving a reply in November 1991. It was Ogino, who didn’t even work for Shueisha but felt so bad for Samon and her heap of unanswered queries that she made a personal call. Ogino now says it was the least she could do.

On the other end of the line, Samon was thrilled. “Someone in my office said, ‘Montse, there’s a call from Japan,'” she says. “And I thought about the faxes and started getting so excited: Oh, Japan! This is my lucky day!”

According to Ogino, the manga industry’s insularity at the time was endemic, rooted in linguistic incomprehension and complacency.

“You see, a lot of foreign publishers wanted to publish manga before 1990, but Japanese publishers just didn’t reply,” Ogino says. “The domestic market was big enough that no one felt the need to respond. Also, there wasn’t any capacity. If you received a fax in those days that you couldn’t read, what would you do? Just throw it away.”

Ogino and Samon arranged to meet the following March in England on the sidelines of the London Book Fair. A licensing deal was signed — “I just made up the one-page contract myself,” Ogino says — and the first legal translation of “Dragon Ball” was published in Spain by Planeta in May 1992. It was an immediate success.

Today, “Dragon Ball” is a media franchise encompassing video and card games, collectibles, theme park attractions and an ill-conceived Hollywood live action film released in 2009 to near universal condemnation. It’s one of the best-selling manga series in history, second only to Eiichiro Oda’s “One Piece,” which is also published by Shueisha. Ogino is now the director of Tuttle-Mori’s Manga Department and oversees a full-time staff of 25, while Samon sells manga titles into other Spanish-speaking territories such as Mexico and Argentina. The two women have become close friends, their lives changed by manga and faxes.

“Dragon Ball’s” orange-suited, spiky-haired protagonist, Goku, is a perennial favorite for cosplayers, especially at anime conventions, the massive Japan pop culture fan gatherings that rose and proliferated in the past 20 years, and whose attendance figures continue to grow.

However, Goku was soon upstaged by another now-iconic anime figure that came out of the Heisei Era. Pikachu, the bright yellow rodent-like monster of “Pokemon,” whose lightning bolt tail is nearly as spiky as Goku’s hair, has a balloon likeness that soars annually alongside Spiderman and Bullwinkle over Manhattan’s Sixth Avenue as part of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York.

“Pokemon” was launched in Japan in 1996, and rolled out worldwide over the following two years. Unlike “Dragon Ball,” it started as a game rather than a manga, though its basic concept — an adventure based on a real-life childhood obsession in Japan (insect-collecting), endless serial episodes and multiple characters — perfectly suited manga and anime renderings. Originally created by Satoshi Tajiri, the game and its infectious narrative were an instant hit with Japanese children.

“We knew right away that (‘Pokemon’) would sell all over the world,” says Masakazu Kubo, director of Shogakukan’s International Media Business Department. “Japanese kids are the most demanding child consumers on the planet. If they love something, other kids will love it, too.”

The series’ narrative and design were meant to be seductively simple and endlessly protean. Pikachu’s visual outline, the character’s silhouette, was as critical to the story’s global reach as Snoopy’s nose and McDonald’s golden arches, and its multiple platforms provided fans with constant access to the content.

“One of the key reasons ‘Pokemon’ became a worldwide hit is its cross-media strategy of games, animations and card games,” says Kubo, who published a book titled “Pokemon Story” in 2000. “This is something that animation characters made in Hollywood studios had not yet been able to accomplish.”

As Kubo predicted, “Pokemon” exploded in world markets in the late ’90s. He traveled to more than 40 countries to help promote and localize the franchise, which meant partly masking its Japanese origins. Like so many of Japan’s intellectual properties, “Pokemon” initially lost a chunk of its profits to foreign distributors: Dense Western-style legal contracts were signed in Tokyo by naive producers who unwittingly gave away all-important subsidiary rights.

“We learned that doing business elsewhere is very different from doing business in Japan,” Kubo says. “That mistake was our fault.”

“Pokemon” and “Dragon Ball” are now mainstays of the anime and manga phenomenon, and both remain active properties: Two years ago, “Pokemon Go,” the mobile gaming app, radically changed the augmented reality landscape, and a first “Pokemon” live-action feature film is scheduled to be released next year; “Dragon Ball Super: Broly,” the latest franchise anime feature, will be out in December. Both are Heisei Era emblems of Japan’s shift from physical manufacturer to pop culture wellspring.

I became personally involved in this story in 2006, when I was living in New York. An editor at Palgrave Macmillan asked me if I would consider writing a book about the prominence of Japan’s soft power in the 21st century. I declined at first, deferring to otaku (obsessive fans). But as I read and thought and wrote about the global shifts that were taking place in mind and culture, I began to warm to the pitch, and produced a book about the story of Japan’s Heisei Era enchantment of the West called “Japanamerica.”

It was a heady time. Independent publishers and cable television stations such as TokyoPop and the Cartoon Network opened doors to Japan’s cultural innovations and libertarian stories. In 2003, Miyazaki scored an Oscar for his film “Spirited Away.” The expansion of broadband internet file-sharing platforms such as YouTube and the proliferation of fan-produced anime sites made Japanese pop culture accessible to anyone with a dial-up or Ethernet connection. (In the summer of 2005, YouTube’s most popular genre was anime; six University of California, Berkeley engineering students took note and dreamed up Crunchyroll, today’s premier dedicated anime streaming platform.)

Japan’s native pop-cultural products have now survived the hits of the 2008 global recession, and Japan’s 2011 natural and nuclear disasters. They continue to thrive as the Heisei Era comes to a close. Streaming media giants such as Netflix and social networking sites have only enhanced their appeal, Horibuchi says.

“Japanese pop culture like anime and manga should always stay a part of the subculture, because fans love to talk and share their passion for them online,” he says. “Japanese pop culture is the best kind of subculture, because the quality is so good. But it shouldn’t compete with Hollywood, because that’s too much money. ‘Mainstream’ means money, and that would ruin it.”

The Heisei Era will conclude next April with the abdication of Akihito, Hirohito’s son, an intellectual with a passion for ideas, culture, science and civility. His decision to seek retirement before death is unprecedented, but his willingness to bare personal reasons for reprieve, in stark contrast to the secrecy surrounding Tezuka’s declining health, suits the Japan of this century, and the international fans who love its creativity and candor.

Compared with so much of Western pop’s tired innuendoes, ironies and increasingly politicized racial and sexual controversies, anime and manga often feel more like earnest expressions of personal yearning and the pleasure of entertainment. Through shared media, diversity and longing, individuals around the world have come to love Japanese culture through its most embraceable, if imaginary, gods: Goku, Pikachu and Astro Boy. Money might well ruin it.

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” and a writer in residence at the Catwalk Institute.