SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 5

Innovation

Game on: A collection of game console controllers, including the Sony PlayStation and the Sega Dreamcast. | GETTY IMAGES

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the fifth installment of a series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades. This installment follows Japanese games as they go global

JASON COSKREY

Staff writer

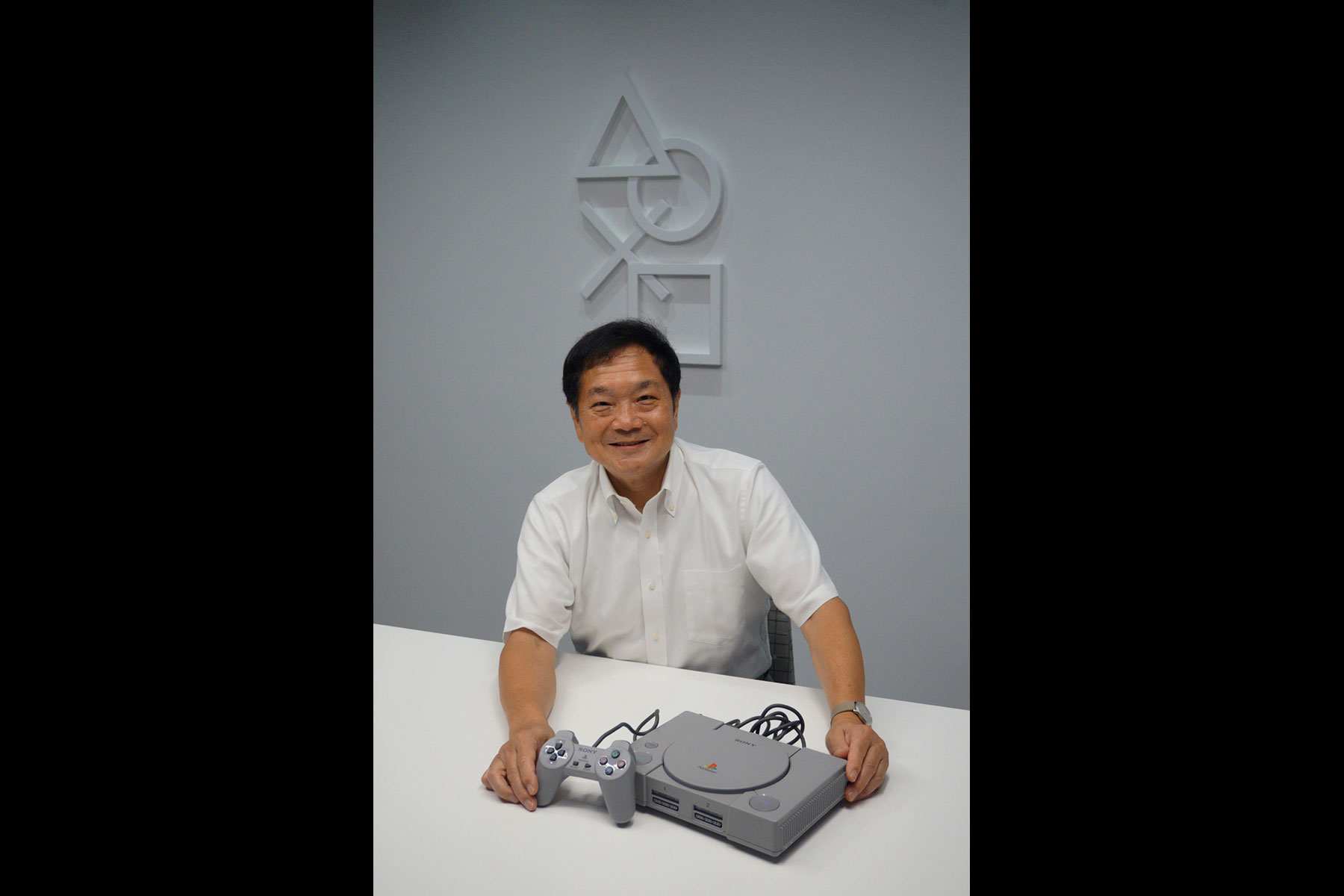

Ken Kutaragi is feeling a little anxious. He has already long established himself as one of the brightest minds at Sony, but today is like being a newbie all over again. That’s because on this particular morning, Dec. 3, 1994, the machine that’s essentially his life’s work, the Sony PlayStation, is about to be released.

Kutaragi spent the previous night with software creators and others at a pre-release party in the Tokyo neighborhood of Ebisu. Now, he and members of his team have spread out across the capital to monitor the PlayStation’s debut.

As the launch creeps closer, Kutaragi’s mind is racing. Would people buy the system? The electronic stores were set to open at 10 a.m., were PlayStations already on the shelves? Was everything going to run smoothly?

“We went to check and surprisingly there were already long lines,” Kutaragi, now widely known as the father of the PlayStation, tells The Japan Times on a windy September night at Sony’s headquarters 23 years later.

“The people waiting for the PlayStation weren’t elementary school kids, they were in their 20s, 30s and 40s,” Kutaragi says. “It was also a surprise to see couples there. Until then, games seemed to be only for boys. After the release of PlayStation, however, I saw more women. At exhibitions and events, there would be couples and also women who came alone.

“I had been hoping for that kind of result, but seeing it made me think this was going to be a success as a form of entertainment.”

Describing the launch as a success would prove to be an understatement.

The PlayStation was, for lack of a better word (pardon the pun), a game-changer, turning the video game industry on its head in the Heisei Era (1989 to the present day). Its 3D graphics, games and sheer cool factor took gaming worldwide.

“PlayStation was obviously super successful in bringing 3D home. Sega Saturn less so,” says James Mielke, creative director of game studio Tigertron and former editor-in-chief at Electronic Gaming Monthly. “PlayStation whet the appetites of everybody who wanted games.

“I don’t know if it was the timing or it was because of 3D in particular, but home consumers really wanted these new 3D games. It stopped being like a weird, niche, hard-core hobby and something a wider, more general populace could enjoy.”

The system’s broad appeal, from children to adults, was one of its strengths and had been a point of pride.

“I didn’t want to make games for a specific cluster of children,” Kutaragi says.

The PlayStation was among the first consoles to rely on 3D graphics, as did the Sega Saturn, which was released the same year.

Kutaragi was a film buff — he joked he might have been the seventh person in Japan to create a home theater — and had been partially inspired by advancements in Hollywood in the late 1980s and early ’90s.

“Nobody was really making 3D games,” he says. “Everybody thought it would fail. I didn’t think so. When computer graphics came to the movie industry, they were able to make so many amazing films. They were able to express things people hadn’t seen before. I thought we could create that in games. So I gathered a lot of Sony engineers and said, ‘Let’s do it.’”

3D revolution

In 1993, Sega released “Virtua Fighter,” the first 3D fighting game, in Japanese arcades. “Virtua Fighter” was a hit, and Kutaragi was even more determined to bring the 3D experience into homes.

“There were these big arcade machines, but (I thought) it’d also be fun if people could play at home,” he says. “They could practice at home and then go out and fight in the arcades.”

He looked for a gamemaker to help support the idea, but was initially rebuffed.

“Namco also said it was impossible, but at the same time said, ‘Let us see it,'” Kutaragi says. “They were really surprised. They said, ‘Is Sony really doing this?’ They stopped internal development and said, ‘We think this is amazing. We’ll make amazing games for it.’ That led to one of the PlayStation’s launch titles. The first one was ‘Ridge Racer.’ They later created ‘Tekken.'”

The PlayStation, after first duking it out with the Sega Saturn in Japan, would later become a smash hit worldwide. A 2017 report from gaming site “Gamespot” lists the system as the fourth bestselling console of all-time — the PlayStation 2 topped the list.

In 2004, Time magazine named Kutaragi in its list of the 100 most influential people in the world for his work on the first two PlayStations.

“If video games are the storytelling medium of the coming century, Kutaragi is their Gutenberg,” the magazine said, referring to the creator of the printing press.

“It was the shiny new thing, for sure,” Mielke says. “There was no denying the PlayStation could do actual 3D polygons, not like fake, funky polygons. It could do all these new things we’d never seen before.”

Mielke believes timing, coming along when 2D gaming had just about run its course, was also crucial.

“I remember one of our writers at GMR and 1up.com, back in the day we did an article about Japanese games that hadn’t been brought over to the United States,” he says. “He made an observation in the article that said, ‘This came at a time where publishers were more interested in poor-looking polygons than beautiful-looking sprites.’”

Sony eventually attracted robust third-party support, and the PlayStation became home to classics such as Konami’s “Metal Gear Solid” and Capcom’s “Resident Evil.”

There was also “Final Fantasy VII.”

To achieve Kutaragi’s vision, the PlayStation used CD-ROMS as its primary format instead of cartridges, the standard at the time. Discs were cheaper to produce and held more memory, enabling developers to use more advanced graphics and pre-recorded music, among other advantages.

Japanese developer Square had made the previous “Final Fantasy” titles for Nintendo systems and had grandiose plans for the seventh installment. But when Nintendo decided to stick with cartridges for the Nintendo 64, Square moved “Final Fantasy VII” to the PlayStation.

“Final Fantasy VII” was released in 1997 as a sprawling epic — with an engrossing story and dynamic soundtrack to match — that spanned three discs. It used 3D, CGI cutscenes and was about as close to a movie as a game had come.

One U.S. TV commercial summed it up thusly: “More than 200 animators and programmers. A multimillion dollar production. Over two years in the making. And a cast of thousands. They said it couldn’t be done in a major motion picture. They … were right.”

The costs were exorbitant. Gaming site Polygon released a “Final Fantasy VII” oral history, authored by Matt Leone in 2017, in which former Square President and CEO Tomoyuki Takechi spoke about the production costs.

“We used about $40 million (approximately $61 million in 2017 with inflation, according to Polygon) for the game’s development,” Takechi says. “We probably spent $10 million of that just on the computer graphics.”

In 2014, Business Insider included “Final Fantasy VII” on its list of the most expensive games ever made at $145 million (including marketing), or $214 million adjusted for inflation.

The game displayed the type of experience video games could create. It showed games were worthy of blockbuster budgets and drew the blueprint triple-A releases follow even today.

“Final Fantasy VII” was a best-seller, and played a role in Sony usurping Nintendo in the gaming market. It also sparked a boom in Japanese role-playing games abroad.

Rising fortunes

Even prior to the PlayStation’s arrival, the early Heisei Era years saw developers of Japanese games dominate the industry.

The 16-bit era had dawned and the console war between Nintendo’s Super Nintendo and Sega’s Genesis (essentially “Mario” vs. “Sonic the Hedgehog”) dominated playground arguments in the West.

“When the 16-bit era came along everything was just bigger and better,” Mielke recalls. “This was when video games started realizing their potential, especially in 2D. And the majority of the hardware dominating the market, whether it was the Super Nintendo or the Genesis or the TurboGrafix(-16), those were all Japanese products.

“Because they were so successful in Japan, just like anything else, the economics of it made it sensible for Japanese developers to jump on and make these games. It was a self-fulfilling prophecy. It was like, the consoles are popular in Japan, we want to make money. Let’s us, the Japanese game developers and publishers, make the games. Then they would have these huge homegrown breakout hits like ‘Dragon Quest.'”

Just as the era saw the global rise of the Japanese gaming industry, it also bore witness to its fall.

Western developers eventually caught up in terms of skill and were making marquee, best-selling games more suited to Western tastes, such as Rockstar’s “Grand Theft Auto” series and first-person shooters such as Activision’s “Call of Duty.” Microsoft also emerged as a major player, outside Japan, with its Xbox console in 2001.

When Forbes published a list of the best-selling games of 2017, headed by “Call of Duty: WWII,” only three Japanese titles made the cut.

Mielke traces the shift back to the rise of affordable 3D chips and says things really changed with the original Xbox, which introduced a Windows-based development environment.

“That was hardware Western PC developers could really sink their teeth into and do what they did best,” he says. “Plus, it was profitable. They could put games out on Xbox and then put them on PC.

“That’s pretty much where Japan started losing ground, because Japanese developers were not used to working in Windows environments primarily. They were used to working on this unique, bespoke, boutique hardware such as the PlayStation 3, the PS2, the Sega Saturn, the Sega Dreamcast and Nintendo consoles.

“They were used to working with these proprietary formats that were very specialized. They weren’t really adept at working with PCs, and that’s where the shift took place.”

At the same time on the convention circuit, the U.S.-based Electronic Entertainment Expo and Germany’s Gamescom were beginning to surpass the Tokyo Game Show in prominence. The Tokyo Game Show still draws crowds, having attracted 298,690 fans to Chiba’s Makuhari Messe convention center this year.

“I really like the ‘Metal Gear Solid’ series,” says Kim Young Sun, a 27-year-old South Korean exchange student. “Honestly, I came here because I wanted to see (‘Metal Gear’ creator Hideo) Kojima’s new work, ‘Death Stranding.’ He has a way of telling a story that is very emotional and I wanted to come and check and see what kind of new game he created.”

Kojima appeared on the Sony stage to talk about the game on the final day of the event.

Others attended out of a broader appreciation for Japanese games.

“Japanese games (pay attention to) detail and specification,” says Tommy Dokoro, a 29-year-old Kobe native who attended Tokyo Game Show on Sunday and planned to see the Bandai Namco and Square Enix booths. “I think that is a strong point of Japanese games.”

Michigan native Justin Lach, who is in the middle of a three-month stay in Japan, was attending his first Tokyo Game Show and is also a fan of Japanese titles.

“I always have been,” Lach says. “JRPGs, “Final Fantasy,” “Kingdom Hearts” … all those.”

In his opinion, Japanese games are still improving.

“They’re pretty good,” he says. “They’ve gotten better. The graphics are better, some of the systems, the way they play, are better now than they used to be.”

Japan has fought back against the westward shift in recent years with blockbusters such as “The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild” and surprise hits such as “NieR: Automata” and “Octopath Traveler.”

Going mobile

Yohei Kitabayashi saw the Heisei Era in gaming pass right across his counter. Kitabayashi is the manager of Super Potato, a three-floor shop in Akihabara full of retro games and systems, and other items, popular among casual gamers and collectors alike.

Kitabayashi has worked at Super Potato for 15 years, surrounded by Nintendo Famicoms, Sega Dreamcasts and games for the PC Engine and so forth. From here, he has been able to watch gaming evolve.

“There was Famicom in the ’80s and then from the ’90s there was Super Famicom and gaming really exploded,” Kitabayashi says. “Then Game Boy came out and gaming really spread around the world. There were so many ways to play games: on consoles, on handheld systems and now you can even play on your keitai (mobile phone). You can play anywhere and I think that’s made a huge impact.”

Nintendo released its Game Boy handheld system in 1989. It was bulky, light gray and didn’t play games in color like the sleeker Atari Lynx and Sega Game Gear. What the Game Boy had was superior battery life and quality titles — specifically “Super Mario Land” and “Tetris” — that set it apart. Later, the system would be the launching pad for the “Pokemon” game series.

Nintendo has dominated the handheld market with its various consoles ever since. Last year, the company released the Switch, a hybrid machine that can function as both a home console and handheld machine, to great demand and fanfare.

By 2007, gaming on phones had begun to take hold, which Kantan Games (a game industry consultancy focused on the Japanese market) CEO Serkan Toto says, “disrupted the gaming industry here in Japan.”

“When you talk about gaming, you basically have three pillars,” Toto says. “You have the PC gaming segment, the console segment and the mobile segment. In Japan, only the console segment and the mobile game segment actually count. It’s a $12 billion to $13 billion industry, roughly speaking, and mobile games are three-times bigger than consoles. PC games are just a niche market in Japan.

“I believe mobile gaming — first on mobile web games and later as native applications, as smartphones became more popular in Japan — really revolutionized the local gaming industry. Globally, there’s no other developed market where mobile gaming is so far ahead of the other segments in gaming.”

The biggest recent hit has been the addictive “Pokemon Go,” which was launched in 2016 and sent gamers to real-world locations to hunt the titular monsters in augmented reality.

“It’s a worldwide phenomenon,” Toto says. “Here in Japan, I think ‘Pokemon Go’ has found one of its biggest markets.”

Growing indie scene

As gaming technology moved forward, the costs increased. So much so that some major developers became hesitant to take risks, leading to a glut of sequels and predictable titles.

In response, independent games began to gain more traction in the West.

Indie developers didn’t have the budgets of major outfits, but also weren’t beholden to corporate suits and focus groups. They could make quirky, innovative games, sometimes to great success. Today, indie titles are all over the digital marketplaces of Microsoft, Nintendo and Sony.

The movement was slow to take hold in Japan, where being indie previously held negative connotations of being cheap and due to past instances of creators “borrowing” things from other game makers.

That’s where James Mielke comes in.

Having worked for Q Entertainment in Tokyo and Q-Games in Kyoto, Mielke wanted to bring Japan’s fractured indie community together and put developers in the same room as publishers, creators of game engines and international media.

The result was BitSummit, an indie gaming festival that has shone a light on the Japanese indie community from the time it first took place in 2013 and has helped change the landscape ever since.

“What I’ve seen basically is the community getting more efficient at what they want to do and recognizing the whole world as their audience,” Mielke says.

Mielke says the Japanese indie scene is still growing.

“People are better at making games,” he says. “They can make their own original characters, they can animate their own original characters. A lot of the subtle nuances in the development of games in Japan have gotten better. Now that people are doing less of the IP theft stuff and more original games — and being successful — it’s not such a bad thing to be considered indie in Japan. It’s actually pretty cool.

“I think the Japanese indie scene has not only unified quite a bit, but it’s starting to be on a par with the global, Western indie scene.”

A step back in time

The Japanese gaming industry left its mark during the Heisei Era. The revolutionary “Super Mario 64,” in particular came out in 1996, and its influences are still seen today.

Just two years ago, with the entire world watching, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe emerged from a green pipe dressed as Mario as part of the Olympic handoff at the closing ceremony of the Summer Games in Rio de Janeiro.

Virtual reality setups are all the rage now, but they’ve come decades after Nintendo’s ill-fated Virtual Boy.

Similarly, the first system to ship with an internal modem, to facilitate online play, was Sega’s Dreamcast in 1998.

All can be seen at Super Potato, and shops like it, where the Heisei Era’s gaming past will live on as time moves forward.

“Many people come here, from both inside Japan and overseas,” Kitabayashi says. “It doesn’t matter if they buy things or not. They don’t necessarily have to buy things but when they see what we have here, they get very nostalgic.”