SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 4

Pride

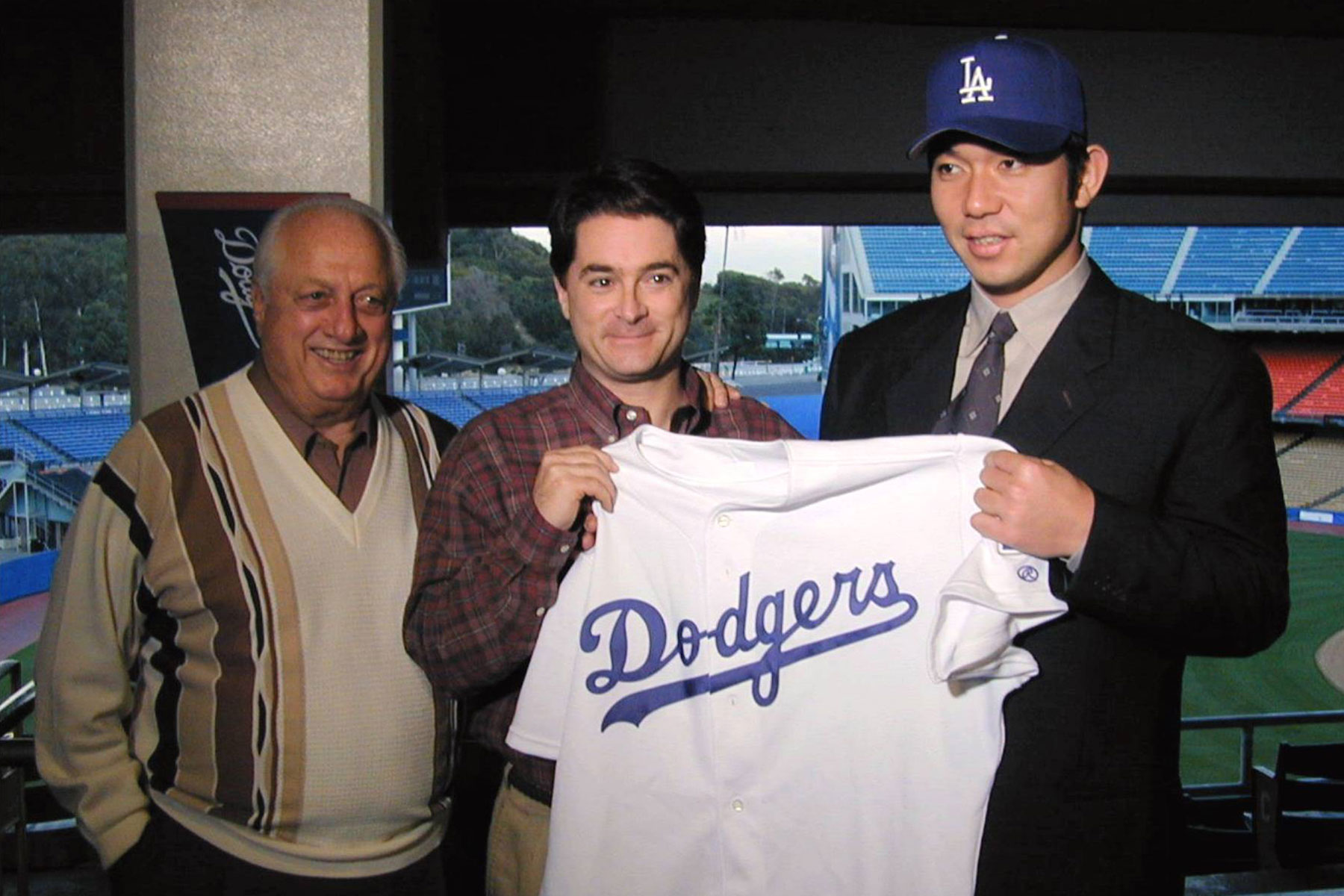

Leading the charge: Spectators in Shinjuku watch Hideo Nomo of the Los Angeles Dodgers pitch in a Major League Baseball All-Star Game on July 12, 1995. | TOSHIKI SAWAGUCHI

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the fourth installment of a series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades. This installment follows Japanese sports as they go global

ANDREW McKIRDY

Staff writer

Hideo Nomo walks down a corridor deep within The Ballpark in Arlington, Texas, calm and smiling as he high-fives a long line of children calling out his name like a nest of chicks begging for a worm.

Outside the stadium, a Japanese TV announcer is struggling to compose himself.

“Can you believe it?” the announcer asks, as much to himself as to the audience back home. “Can you believe it?”

In Tokyo, more than 1,000 fans are gathered in front of Studio Alta’s big screen near Shinjuku Station, having arrived hours before the 9:30 a.m. start of the live telecast.

“I came here to share in the excitement, and to see how the Japanese would react,” says Kevin Furuta, a 27-year-old Japanese-American student from Los Angeles.

It is July 12, 1995, and “Nomomania” has reached its zenith. The Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher is preparing to make history as the first Japanese player ever to appear in Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game, and the impact is nothing short of epoch-defining.

“Americans couldn’t name Japan’s prime minister, they couldn’t name Japan’s top singer or actor, but they knew Nomo,” says Robert Whiting, author of several best-selling books about Japanese baseball. “He became this icon. It really made a difference in U.S.-Japan relations.

“The Foreign Ministry’s website gauged relations between Japan and America. It starts out that the Japanese opinion of America is really high at the end of the Occupation in 1952. Then it went downhill throughout the ’50s because of all the GI crime and security treaty demonstrations, and on through the trade disputes and the bubble era. It was at its lowest peak just before Nomo went, and then in 1995 there was this huge spike, really noticeable, where opinions of America went up.”

No discussion of the seismic changes that have occurred in Japanese sports over the course of the Heisei Era (1989 to present) would be complete without Nomo — a taciturn young man with a distinctive pitching style who blazed a trail for Japanese players when he signed with the Dodgers in 1995.

Nomo had achieved success with the Kintetsu Buffaloes in Nippon Professional Baseball after making his debut in 1990, but he wanted more. He had played at the 1988 Olympics and against visiting MLB teams in Japan, and his desire to test himself against the world’s best on a regular basis had grown accordingly.

At the time, however, the idea of Japanese players moving to MLB clubs was practically unheard of. Masanori Murakami had been the only one to do it when he joined the San Francisco Giants in 1964, but Japanese baseball had since tightened the rules to make it harder for others to follow his lead.

Nomo looked stuck, until a meeting with Japanese-American baseball agent Don Nomura changed his fortunes. Nomura found a loophole in an agreement between NPB and MLB that would — in theory — permit players who were voluntarily retired to sign with major league teams. All he needed was a player with the courage and conviction to take on the Japanese baseball establishment.

Enter Nomo, who gave the Buffaloes a demand for a greatly improved contract that he knew they would never agree to, effectively daring them to put him on the voluntary retirement list. When the team took the bait, Nomo and Nomura were free to make their move. The response to the announcement that he would join the Dodgers was so vitriolic that Nomo’s own father turned against him, but public opinion soon shifted when he began to find success on the field.

“Until his first pitch on May 2, 1995, every newspaper was tearing him down,” Nomura recalls. “After his first game, I think some of the people were very surprised by how it had turned out. They thought he was going to get blown off the field. Then slowly his numbers kept creeping up, getting better and better.

“After his first win, there was a 180-degree change from the press. And the people of Japan were watching him on these huge TVs in Shibuya. The whole country was rooting for him. What happened six months before — everyone forgot.”

Nomo’s success paved the way for a new generation of Japanese baseball players, all hungry to prove themselves in the major leagues.

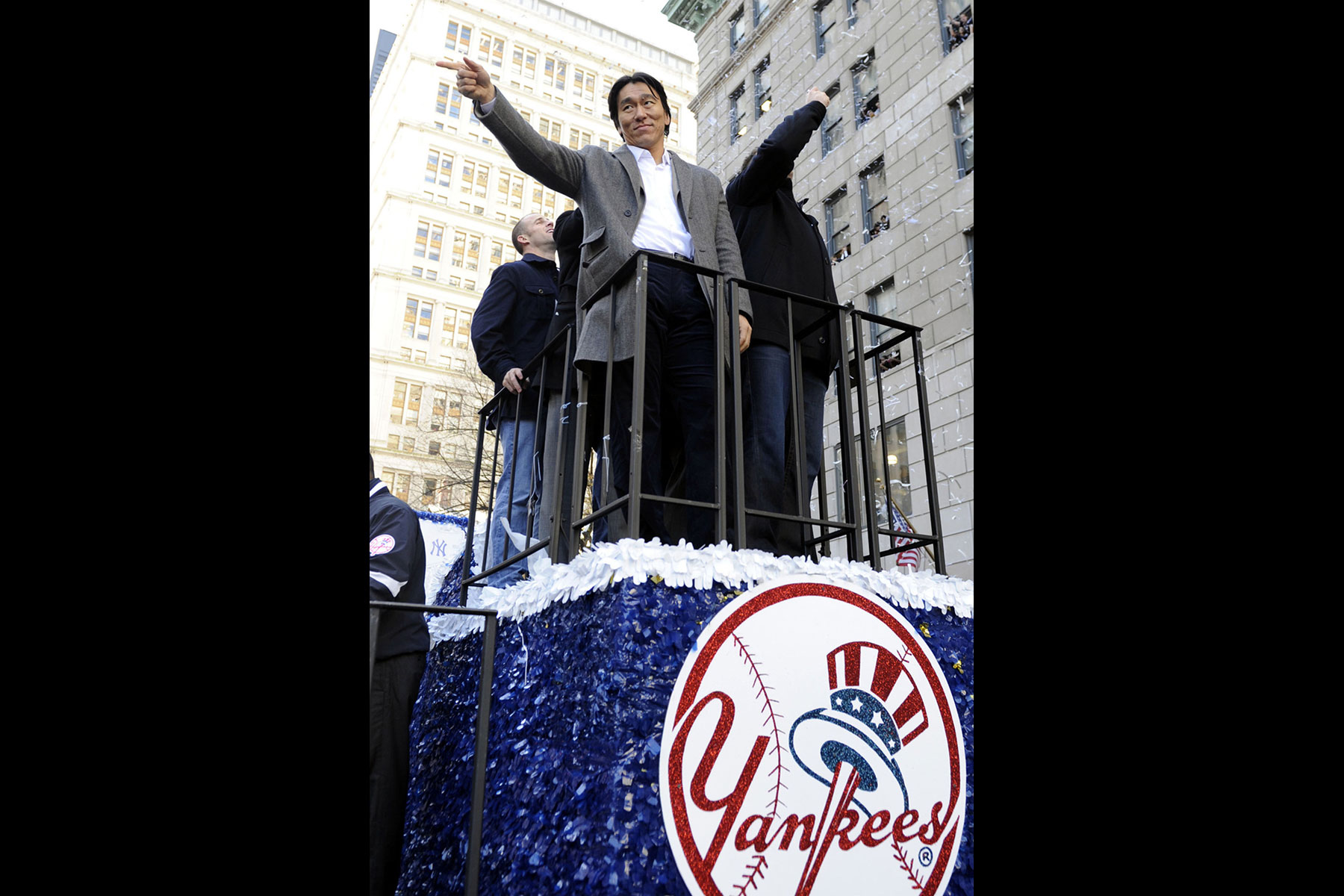

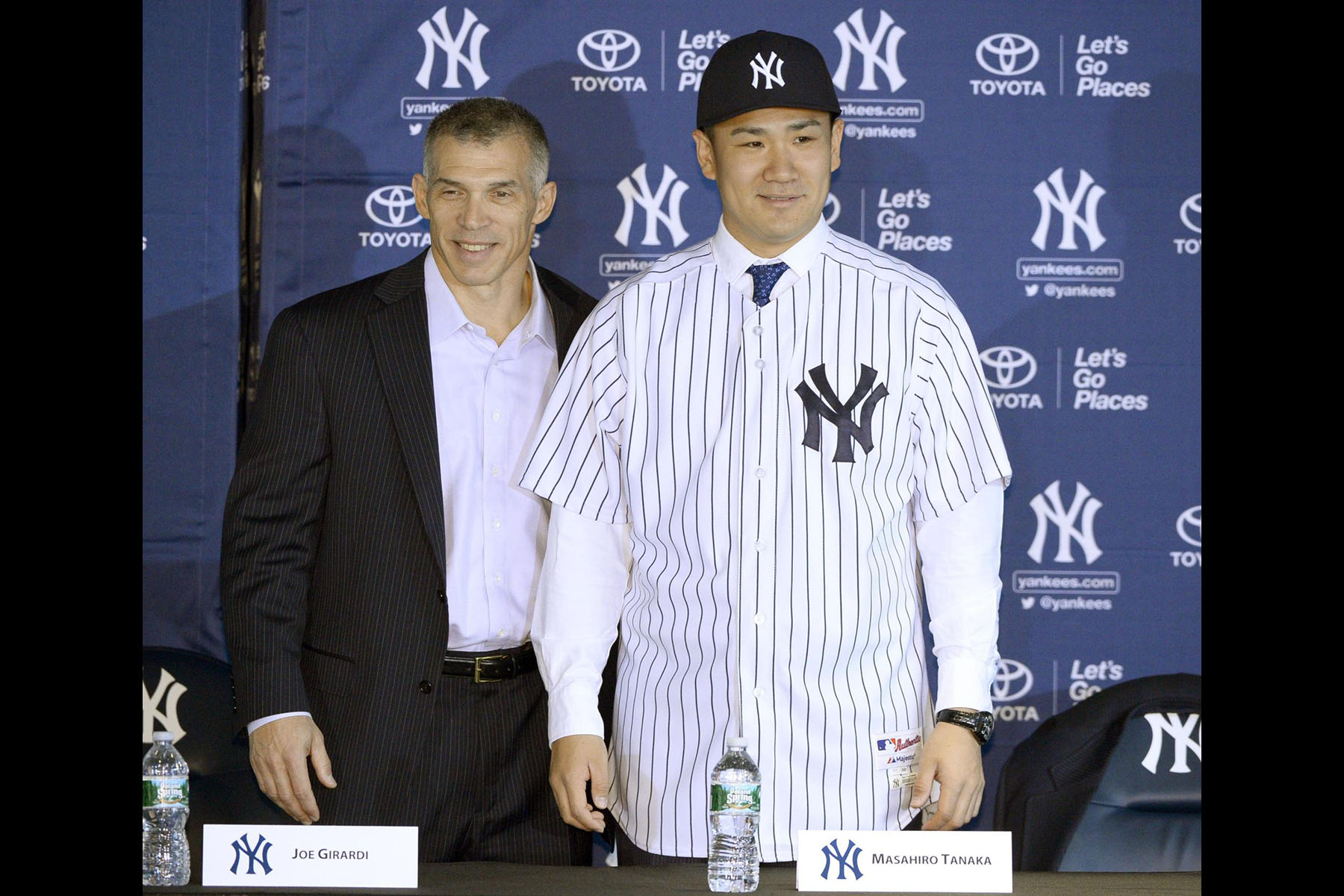

Ichiro Suzuki joined the Seattle Mariners and was named Most Valuable Player of the American League in his first season. He would later break the MLB record for the most hits in a single season, an achievement that had stood for 84 years. Hideki Matsui signed with the New York Yankees and was named MVP of the 2009 World Series. Pitcher Masahiro Tanaka also joined the Yankees, winning a contract so massive that he was able to charter a jumbo jet out of his own pocket to fly him, four family members and his pet dog to New York.

“Three or four years ago, Tanaka was the Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles’ big star,” Whiting says. “The owner of Rakuten, Hiroshi Mikitani, was thinking of keeping him in Japan for another year, but the fans in Tohoku really wanted to see Tanaka go to the States. They wanted him to play with the Yankees. I’ve read that Mikitani did a survey of what would happen if he kept Tanaka in Japan for another year, and the survey concluded that the price of Rakuten’s stock would go down because the fans wanted Tanaka to go to the U.S. so much.

“They wanted him to become this global star. That would give the community more prestige. So that’s how much it’s changed. It’s gone from, ‘You’re a dirty rotten traitor if you go to America’ to, ‘There’s something wrong with you if you don’t go.’ That’s a huge change.”

The pride that Japanese sports fans began to feel about seeing their own athletes succeed overseas in the Heisei Era wasn’t just limited to baseball.

Soccer had never previously enjoyed much popularity in Japan, with the corporate Japan Soccer League pitting teams of player-employees against each other in front of sparse, disinterested crowds. The launch of the professional J. League in 1993 changed that virtually overnight, with its lineup of big-name overseas players and flashy marketing casting a spell over the entire nation.

“You couldn’t miss it,” recalls Florent Dabadie, a French journalist who first arrived in Japan in 1994 and went on to serve as Japan manager Philippe Troussier’s translator during the 2002 World Cup. “Everybody was wearing J. League uniforms and all the shows on TV were talking about soccer. I’ve never seen anything like it. I’ve seen pretty big sports towns like Green Bay and Dallas and the Yankees in New York. There it’s part of the culture, but here those soccer players were rock stars. It was like the Rolling Stones coming to town every Saturday.”

The J. League broke new ground by stripping teams of their corporate identities and replacing them with names that represented the communities where they were based. Teams such as Kashima Antlers and Urawa Reds became the new symbols for towns that had never previously had much to shout about, establishing a firm base that would remain long after the initial hype had died down.

“We wanted the clubs to put down roots in the towns where they played so that people would support them,” recalls Saburo Kawabuchi, the J. League’s first chairman. “That would bring in more fans and sponsors. The most important thing was to make it about the towns where the clubs played. That wasn’t the case in Japan but it was common practice in Europe.

“Sports in Japan have now become more centered around places. That culture started with the J. League. Professional baseball began to take notice and started doing more to increase its support in towns and cities. The J. League has had a big influence on all sports in Japan.”

The launch of the J. League also helped to strengthen Japan’s national team, and led to a first-ever World Cup appearance at France 1998. Japan had missed out on a place at the previous tournament four years earlier in heartbreaking fashion, conceding a last-minute goal against Iraq that became known as the “Tragedy of Doha.” Kawabuchi believes it was a watershed moment.

“That was the first time that people in Japan had experienced the feeling that soccer can give you, where you go from heaven to hell in just one moment,” he says. “In baseball you often get go-ahead sayonara home runs, but that doesn’t happen in soccer so people thought it was a boring sport. Then the Tragedy of Doha happened, and people in Japan went through all that in a matter of seconds. The TV ratings for that game were 48 percent. That’s still a record for TV Tokyo. People discovered that soccer could give you that kind of moment.”

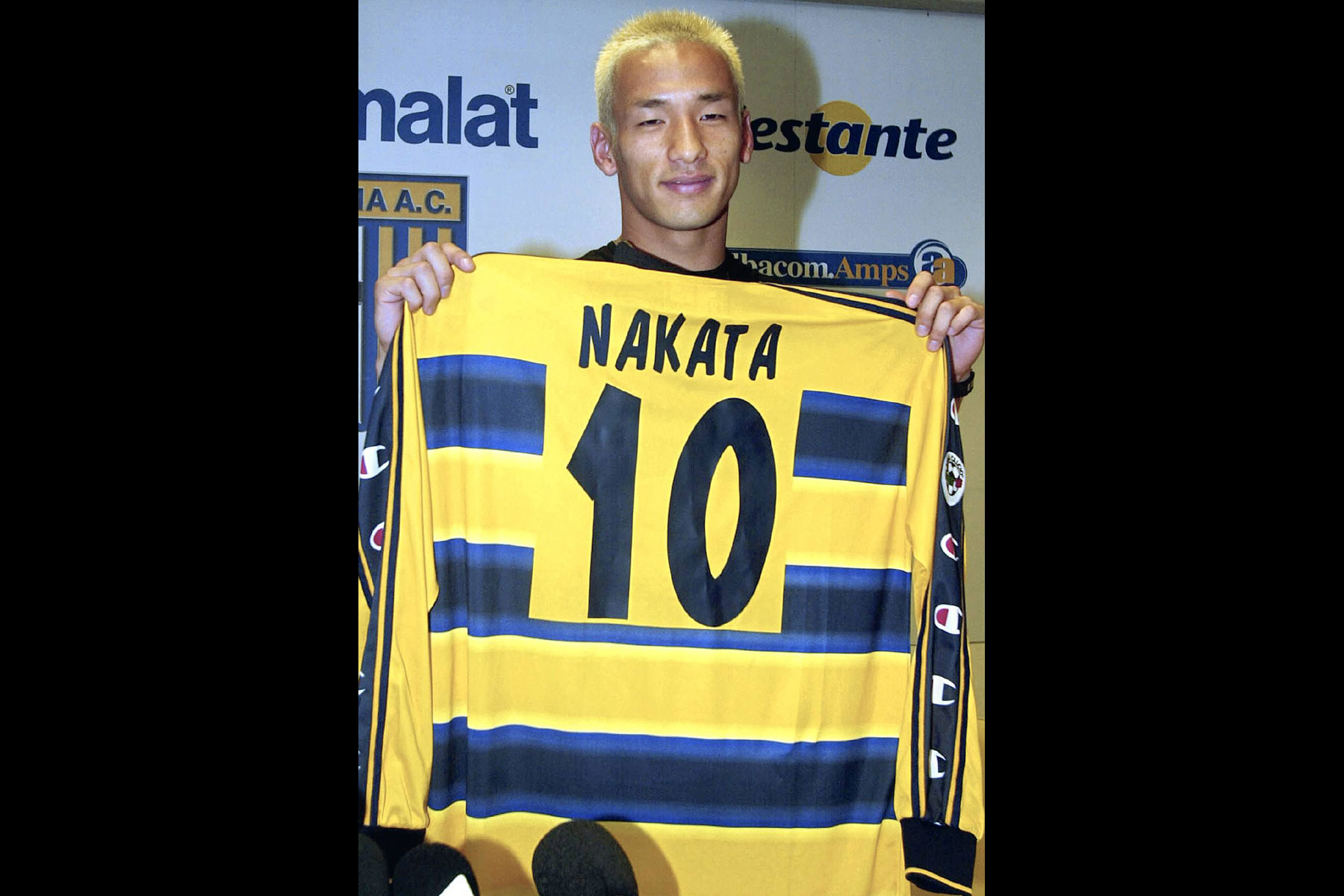

Homegrown J. League players such as Hidetoshi Nakata and Shinji Ono soon began to join big European clubs, doing for soccer what baseball players like Nomo had done before them.

“Those guys have done more than any politician or diplomat ever did,” says Whiting. “The power of an individual in various sports — in this case with Nomo and Nakata — is transformational. It symbolizes something more than itself.

“Before these athletes went, Japan was just noted for the products it made. They didn’t really feel respected as people because they didn’t really have any symbols. It wasn’t until these guys came along that they were elevated to that level.”

The rise of Japanese soccer even saw the country co-host the 2002 World Cup with South Korea, bringing one of the world’s premier sporting events to Asia for the first time.

“It was 10 years since the J. League had begun and it was time to show the world that they didn’t just splash money and make it a circus, but that they had really learned and had promising young players,” Dabadie says. “I felt that there was a tremendous pride from the officials and the fans to show that not only did they love soccer for real, but also that they could play. Japanese players were still exotic to the foreign eye and they felt that they deserved a little respect.”

The 2002 World Cup was not the only major international sporting event Japan hosted during the Heisei Era. The 1998 Nagano Games brought the Olympics to Japan for a third time, following the 1964 Summer Games in Tokyo and the 1972 Winter Games in Sapporo.

The Nagano Olympics captured the nation’s attention during the 16 days of competition, but also left a questionable legacy. The extension of a shinkansen line to Nagano was offset by lower-than-expected tourism numbers, while huge cost overruns and a corruption scandal that had bid committee members destroying financial records left a sour taste in the mouths of many.

“The people who lived in Nagano had to go through about 12 years of all the hoopla surrounding the Olympics, and it was over in two weeks,” says Masao Ezawa, a Nagano craftsman who led a grassroots movement protesting the 1998 Games. “It was like a typhoon. A lot of people around me had the same feeling. Or to put it another way, I found that a lot of people who live around here had no interest in the Olympics.

“Japan has hosted a lot of sporting events and they are widely reported in the newspapers and on TV. I think Japanese people are easily influenced by things like that. If they say it’s the World Cup, they’ll watch the World Cup. If they say it’s the Olympics, they’ll watch the Olympics. But there’s nothing left once they’re finished. Every time there’s a big sporting event in Japan, I think democracy gets a little bit smaller.”

Japan’s next Imperial era will begin with two more major sporting events: the 2019 Rugby World Cup and the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

An estimated 400,000 fans are expected to arrive in Japan for the six-week-long Rugby World Cup, with organizers receiving applications from 107 different countries for the latest batch of tickets.

The Tokyo Olympics will also give Japan the opportunity to present itself to the world and in turn welcome visitors from overseas. After all the events of the Heisei Era, the nation’s sports fans should find it easy to cope.

“It put foreign news — through sports — on TV,” says Dabadie. “Fuji TV came to me in 2001, and for 12 or 13 years I had a program on TV called World Sports. They wanted me to convey the world through the prism of sports. And it was a very nice program because at the time everyone was curious and they wanted to know about England and Italy and France. Baseball fans were learning about different American cities. Where is St. Louis? Why is Dallas such a big sports town?

“It was a fun way to do something that is very difficult for them to do in school. Because learning just about world history or geography is a bit too abstract.”

According to Whiting, the world will see a more confident, connected Japan when the global sporting spotlight next falls on the nation.

“It’s about national esteem, because they had gone so long without it,” he says. “They had always been thought of as a second-rate country after the defeat in the war, so it really picked them up.

“There was this big shift, and that’s what I think was really significant about the Heisei Era. Japan just really did reach out.”