SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 3

Introspection

Flip your lid: Local “clam”-style Galapagos mobile phones are still popular in Japan. | KYODO

The third installment of a monthly 12-part series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades

PHILIP BRASOR AND MASAKO TSUBUKU

Contributing writers

Every December, news organizations in Japan obsess over words and phrases that have described the local zeitgeist during the previous 11 months. Some of these terms last no longer than a season, but a few have become perennials, entering the vocabulary as standards, understandable to everyone who knows the language.

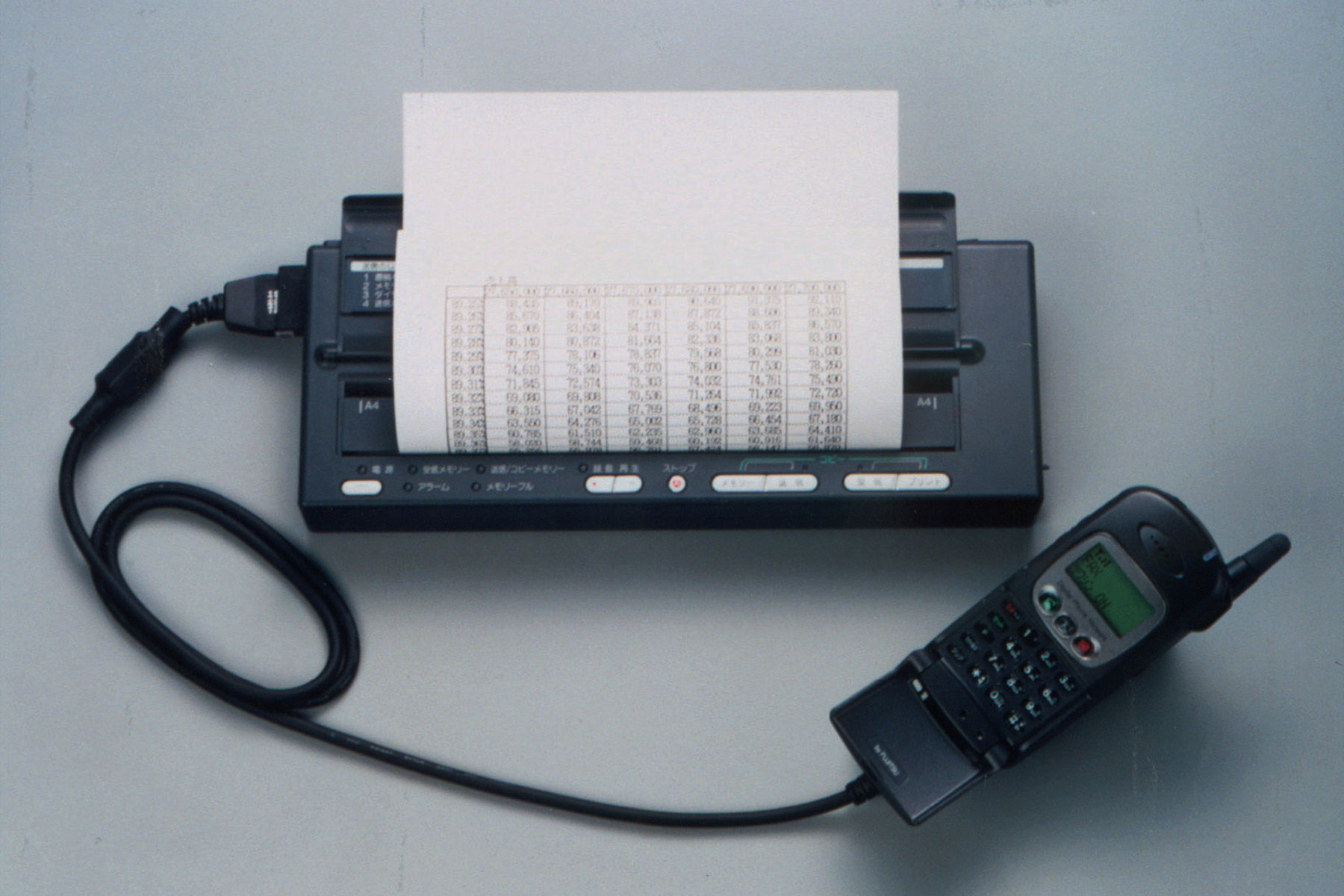

One of the most enduring phrases of the Heisei Era (1989 to the present day) has been “Galapagos syndrome,” which was coined to describe products that were principally made for domestic consumption and which demonstrated no perceivable traction in other markets. The term was initially coined for certain home electronics models and features whose point on the evolution of appliances indicated a closed system, like that of the titular Pacific Ocean islands made famous by naturalist Charles Darwin for their unique animal and plant species.

As a descriptor, however, Galapagos turned out to be flexible, and could be used for a lot of peculiarly Japanese phenomena, such as ATMs that didn’t accept foreign credit cards or the lingering marketability of music CDs well after they had been replaced by digital downloads and streaming in other countries. Another was the concept of Japanese TV personalities called “tarento,” a localization of the English word “talent.” In Japanese showbiz, image and demeanor are paramount, which means TV personalities don’t really need talent. Ostensibly, they are comedians who get jobs on variety shows because they can humorously extemporize about almost anything, and during the Heisei Era, as programming formats became narrower but more refined, so did requirements for tarento. The ability to tell jokes or ad lib was less important than an identifiable trait that viewers would remember and want to see again. Certain TV personalities were hired specifically because they were, conventionally speaking, “unattractive,” or they conspicuously displayed a naive and uninformed view of the world. Such distinctions made these entertainers desirable to producers, who could count on them to act predictably on air in accordance with type.

Although the idea of TV personalities hired for their image is certainly not unique to Japan, the specificity of the image on Japanese TV, not to mention that of the “variety show,” another Heisei invention, made tarento a kind of Galapagos attraction.

Galapagos synergy reached its apex with Shigeki Hosokawa, who some years ago started promoting himself as a kaden haiyu, or home electronics actor, meaning a tarento who could go on TV and speak authoritatively about every type of appliance. Hosokawa wasn’t the only tarento who sold this shtick, but he went deeper. He wasn’t just an expert on home electronics, or even Japanese home electronics — he was an expert on Galapagos appliances.

As a useful term Galapagos has become quaint, but Hosokawa still gets gigs based on his Galapagos boosterism, and in an interview with the weekly magazine Post in May 2016, he explained his enthusiasm.

“Whenever I see a new product,” he told the magazine, “I always think, ‘What is that? How do you use it?’ I get really excited.”

He especially likes products that take Japanese lifestyles into consideration. For instance, Toshiba once developed a drum-type washing machine with external cooling and dehumidifying features that could be used after a person took their evening bath. That’s because in Japanese homes, the washing machine is typically installed in the changing area next to the bathroom, so after your bath, according to Hosokawa, “You can cool off and dry off naturally.”

By 2016, Galapagos products were no longer as ubiquitous as they once were, but Hosokawa remained unfazed. Features that are exclusive to a specific market are what makes Japanese manufacturers special, he told the magazine. Consciously catering to a global market is not the way to go, implying that such strategies are not Japanese. If this approach sounds nationalistic, it should be pointed out that Hosokawa came up with his own term for Galapagos appliances, calling them “hinomaru denki,” or “rising sun electronics,” as opposed to foreign-made products sold in Japan, which are often called “kurofune denki,” meaning “black ship electronics,” named after the military vessels sent by America in the mid-19th century that forced Japan to open its borders to trade.

Denying their Galapagos capabilities means Japanese manufacturers abandon what makes them unique, Hosokawa believes, and, besides, the world has shown that it can appreciate such technologies, even if it has no real use for them.

“If a foreign person wants such a product,” he says proudly, “they have to come to Japan.”

What’s a Sony?

Probably the most Galapagos thing a Japanese media outlet ever did with regard to covering the Galapagos syndrome was to send a Japanese reporter all the way from New York to the Galapagos Islands. The Asahi Shimbun’s former New York bureau chief, Toshihiro Yamanaka, made the epic journey just to find out what people who lived on the islands thought of Japan’s appropriation of their name. According to the resulting article, which appeared in the newspaper on Feb. 16, 2011, the most surprising thing was how populated the islands were. One of the images of Galapagos that led to its use as a metaphor for isolation was that it was home to nothing except giant turtles and iguana. As it turned out, the islands, which belong to Ecuador, had a population of about 26,000 and are a popular tourist destination — so popular, in fact, that local authorities had to make incoming quotas so as to safeguard the fragile ecosystem.

The first thing Yamanaka did was visit a mobile phone store, since one of the most common uses of the term Galapagos syndrome was to describe the features of Japanese 3G mobile phones that weren’t viable outside of Japan. The store he visited had 30 models, mostly Korean. There was one Sony Ericsson. He then went to a home electronics store and, again, it was mostly Korean models such as Samsung, LG and Daewoo. The manager told him that when the store opened 11 years earlier there were many Japanese products, but they had all disappeared — first Yamaha, then Sharp, then Sanyo. He counted them off “like extinct animals,” Yamanaka wrote.

Eventually, the reporter visited the mayor of the town and told him why he came. The mayor was taken aback when he learned that the name of his home was being used to describe products that were only desired by Japanese people. He found the idea insulting and said he might have the Ecuadorian ambassador to Japan lodge a formal complaint.

“I wish you had asked us before using our name,” he said. “Why don’t you just call those products ‘Japanese’?”

‘Bloody good cameras’

It seems fitting that our conversation with futurist Morinosuke Kawaguchi about the development of the Galapagos sensibility is being carried out on the communications software Line, which itself is a kind of Galapagos technology, developed by South Korean engineers for specific use following a breakdown of communications resources during the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 and now the most popular messaging app in Japan and other Asian countries while being virtually unknown in the West. Unfortunately, we keep losing our connection.

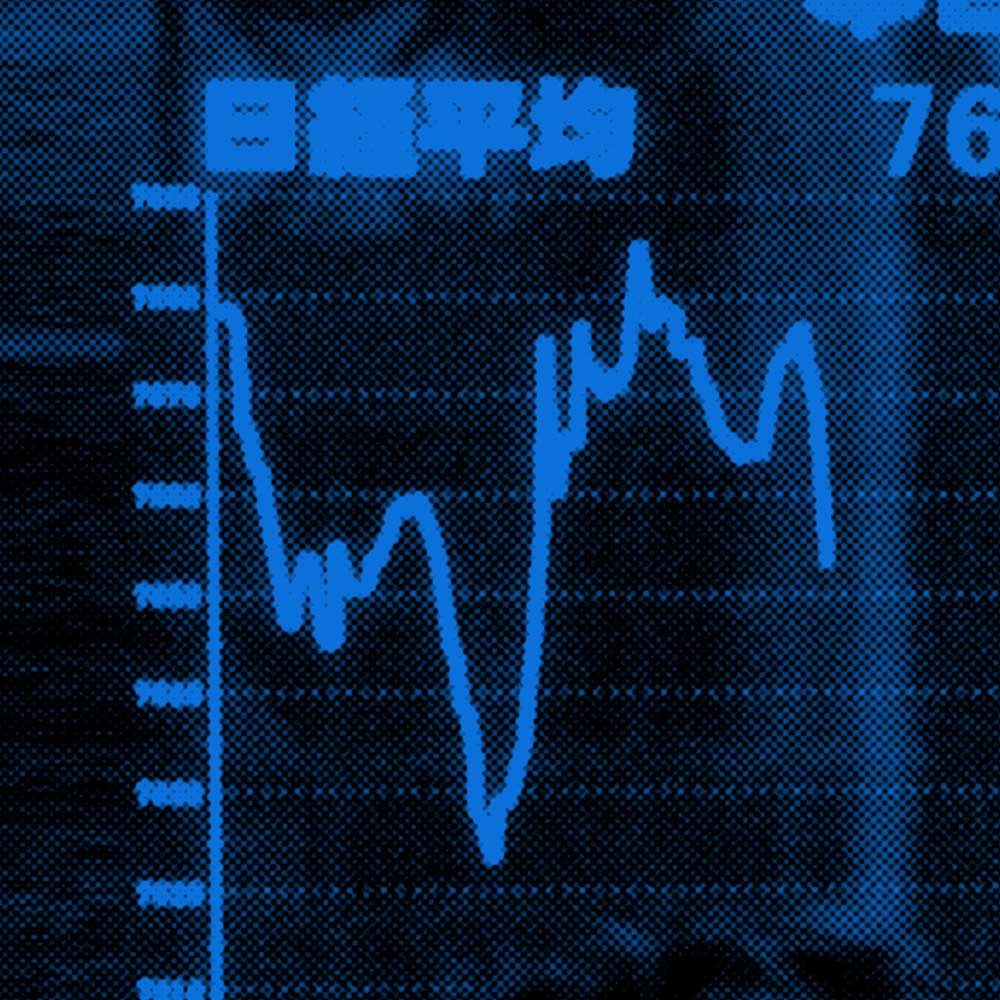

Kawaguchi, an author and consultant who writes and lectures about Japanese technology, is skeptical about the standard narrative of the Galapagos syndrome. Social observers say it arose in reaction to Japan’s loss of global influence in the 1990s after the asset-inflated bubble burst and the country slid into a long retrenchment period. According to this theory, Galapagos represented a more insular, inward-looking stance on the part of Japanese industry and society. Kawaguchi doesn’t buy it. To him, Japan has always been insular and the emergence of Galapagos during an extended period of low growth was mostly coincidental.

“Taking the long view, Japan has always been Galapagos,” he says. “It was a direct result of the Tokugawa family’s way of ruling the country (during the Edo Period, 1603-1868), which limited transportation between villages. As a result, they became more independent of one another and started developing their own local cultures.”

Following the Meiji Restoration of 1868, this spirit extended to the business world. “Every company is different,” Kawaguchi says. “They all have their own company songs and their own corporate cultures. We call it takotsubo culture — you build a wall around yourself and live in a cell. Even during the globalization period, this kind of thinking has been dominant in Japan.”

What impressed the world during Japan’s rapid industrialization following World War II was the diversity of technological creativity, generally referred to as “kaizen,” an idea credited to Toyota Motors of taking something that exists and finding ways to improve it. Kaizen is at base a form of one-upmanship, whether it’s between villages or huge corporations, but the results were impressive enough to change the world’s mind about Japan after the war. As Peter Sellers’ Royal Air Force officer said in the 1964 black comedy, “Dr. Strangelove,” he couldn’t really stay bitter about the torture he suffered at the hands of his Japanese captors during the war because “they make such bloody good cameras.”

“Kaizen is about gradual improvements, not radical innovation,” Kawaguchi says. “The boss doesn’t hand down the idea — just leave the worker alone and they will come up with something.”

This is the advantage of living on an island separated from external dangers, he says. Continental culture is different, because there are always threats. It’s dog eat dog.

“Islands are closed systems,” Kawaguchi says. “It’s a more sustainable culture. The islander says, ‘Let’s make a border between you and me and be nice to each other.’ It’s less aggressive, more conservative.”

In that regard, Japan’s “bloody good cameras” evolved not as a means of earning foreign currency, which may be how the rest of the world saw it. They evolved because of the tendency toward kaizen.

“1970 to 1990 was the age of so-called mechatronics, beginning with Casio’s digital watch and ending with Sony’s Handicam,” Kawaguchi says. “During that time, Toshiba’s Dynabook became the first laptop computer, Minolta came up with autofocus for cameras, G-Shock watches were a big hit worldwide.”

The resulting accumulation of small improvements turned Japan into a tech giant, and as long as electronics focused on distinct functionality — taking pictures, telling time, playing back audio — no one did it better than Japan. But in the ’90s, when everything from cameras to washing machines essentially became computers, these functions were all brought to bear on synergistic products.

“Everything was eventually sucked into the iPhone,” Kawaguchi says.

Japan was great at functionality, but not great at larger integrated concepts. In the ’90s Japan lost its economic mojo as its demographic power waned, which isn’t to say its technical edge has been blunted, only that the edge isn’t as visible as it once was.

“It’s all hidden inside now,” Kawaguchi says. “Japan’s technological know-how is in things such as processors.”

These items are essential for digital products but not as noticeable — and, more significantly, not as profitable — as the integrated digital systems that contain them.

“But hardware makers are not the profit centers anymore,” Kawaguchi says. “Now it’s companies such as Amazon, Google, Facebook and Twitter. Everyone who concentrates on hardware is a loser. The internet is a virtual world, so the winners are not countries but platforms, and almost all the platforms are in America. The whole scene has moved beyond Galapagos.”

Attack of the bots

Earlier this year, many Japanese media covered the work of Fabian Schaefer, a professor at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany, who had just released the results of a study he carried out on social media use related to Japan’s Lower House election in December 2014. Schaefer found that of the 540,000 tweets about the election posted over a 22-day period that coincided with the election campaign and its aftermath, about 430,000 were retweets or slightly modified and duplicated versions of original tweets, and that an overwhelming portion of these were attacks on people who opposed the conservative Liberal Democratic Party and its president, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Schaefer estimated that 80 percent of these tweets were produced by bots, software programs that generate messages and automatically post them on websites. Bots can create the impression that a lot of people are discussing a topic when, in actuality, only a few are.

However, what’s intriguing about Schaefer’s research is his detailed analysis of words used in the tweets, in particular “han-nichi,” or “anti-Japanese,” a derisive term commonly used by right- wing groups to describe anyone they think does not properly support the status quo. As it turns out, “han-nichi” is a relatively new word. Schaefer says it was coined in the late 1990s, around the time Japan was supposedly going through Galapagosization.

“The han-nichi discourse migrated from right-leaning magazines like Seiron and Shokun into (the internet bulletin board) 2channel,” Schaefer says. “It was around the turn of the century that the netto uyoku (right-wing internet users) developed a hermetic ‘cynical’ stance toward mass media, politics and progressive educators.”

What distinguished netto oyuku from more traditional conservative groups was their total disregard for dialogue and debate, a stance they could exploit through the anonymity afforded by the internet.

“Platforms like Twitter or Facebook amplify this cynical communication style,” Schaefer says. “On social media, it is not even necessary to use language, since specific functions — like buttons, hashtags, retweets — enable the user to execute a technical operation that addresses a specific communicative function. (This functionality creates) communities of like-minded right-wingers. It is particularly these high-frequency connectivities that generate ad-hoc publics by merely ‘signaling’ affirmative or negative attitudes, not opinions.”

It’s worth considering if this tendency toward cynical populism was a result of the Galapagos effect or itself a generating factor. As with Kawaguchi’s pronouncement about Japan’s industrial evolution, Schaefer feels that the political and social insularity that seemed to intensify around the turn of the century was organic in nature.

“These are global phenomena,” he says, “and not specific to Japan. Things like filter bubbles and echo chambers on social media have lead to an amplification of Galapagosization on the local level of communities in Japan, and in turn leading to a diplomatic and moral — not economic — indifference toward other countries, especially Japan’s East Asian neighbors.”

Sucking in the Heisei Era

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from Schaefer’s research is that the right wing in Japan is not monolithic, even if its use of social media makes it look big and scary.

By the same token, most of the verities associated with the Galapagos syndrome do not stand up to close scrutiny. Hosokawa thinks that Galapagos products illustrate Japan’s genius for attending to its own needs, and applauds foreign consumers who have the insight to appreciate that genius. However, the idea that these products could never be sold abroad isn’t actually true, or, at least, not in all cases.

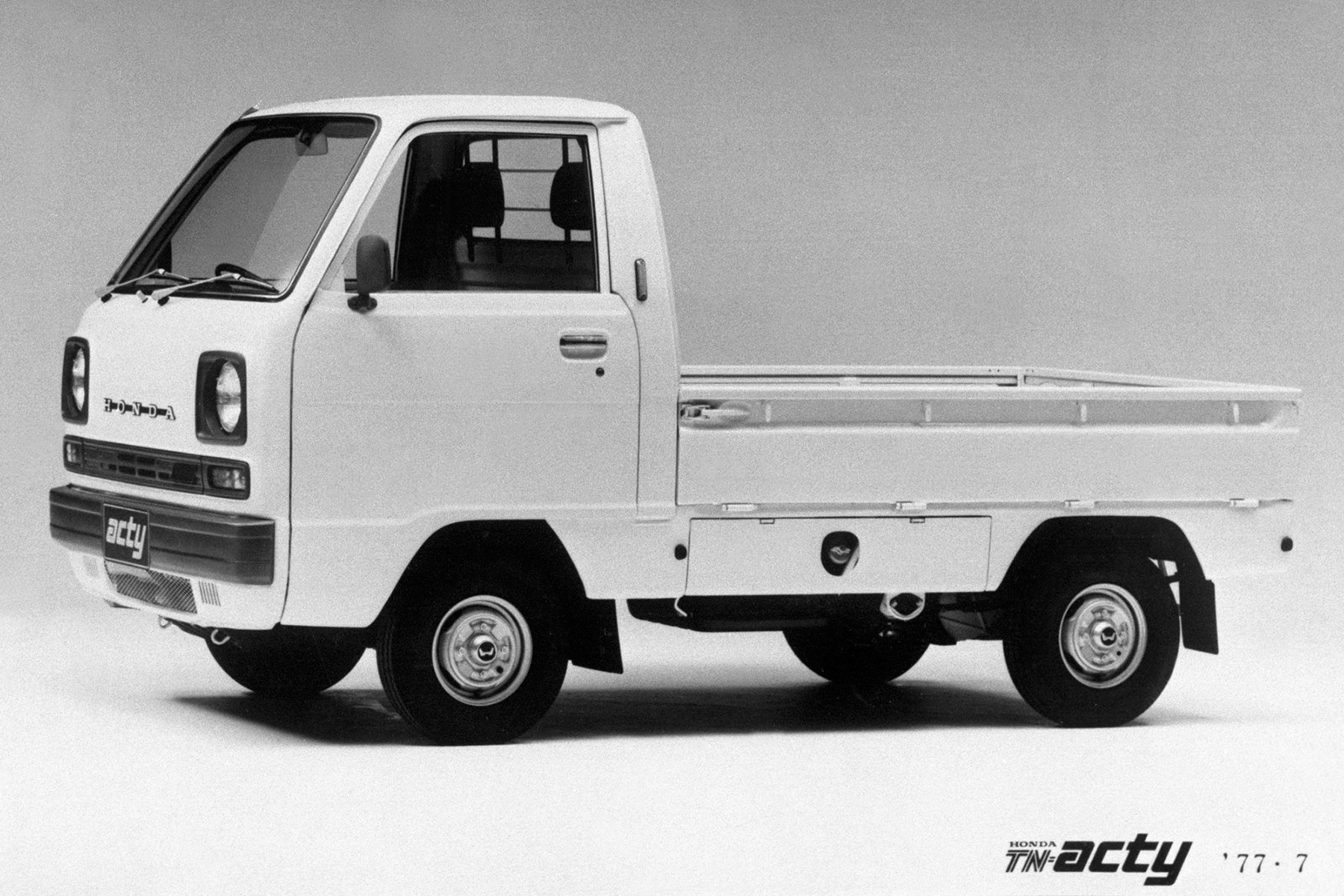

Another item that’s often referenced as Galapagos is kei jidosha, the light automobiles with 660cc displacement engines that are made for Japan’s narrow roads and help alleviate some of the burden of high gasoline prices. Conventional wisdom holds that such minivehicles cannot be sold overseas, but when people say that what they’re really saying is that minivehicles cannot be sold in the United States. Suzuki and Daihatsu, the biggest manufacturers of minivehicles, have been selling them in India for years, and now other Japanese manufacturers are designing such vehicles for Asia.

Another Galapagos product, the electric rice cooker, was at one time considered unmarketable abroad, mainly because of the way Japanese people make and eat rice. They like it sticky and usually eat it plain. However, as soon as Chinese people had enough money to travel for leisure, they came to Japan and bought rice cookers — usually several at a time. As it turns out, the machines, even with all their locally targeted refinements, match the Chinese lifestyle. It’s just that until the past 10 or 15 years, the Chinese couldn’t afford them.

There is even a kind of reverse Galapagosization taking place. Once, a Galapagos feature of Mitsubishi vacuum cleaners was something called “danipunch,” which killed fleas that tend to live in straw tatami mats. Nowadays, flea-zapping isn’t as big a sales point for vacuum cleaners. What is a sales point is how closely a vacuum cleaner resembles a Dyson vacuum cleaner.

Engineer James Dyson wasn’t able to sell his G Force Cyclone technology to any manufacturer in his native U.K., and eventually licensed it to a Japanese company in the 1980s. With the money he made from the deal he started his own company, which has since become a top world brand for vacuum cleaners and air circulation devices. However, when he started exporting his own machines to Japan in the ’90s, they didn’t sell well, mainly because they were expensive, loud and heavy. However, Dyson knew the Japanese market and what it took to make it here. He did his own kaizen, resulting in machines that were lighter, smaller and more powerful. He also introduced the idea of a cordless vacuum cleaner, and then improved battery life and weight. Dyson products are still expensive, but Japanese consumers are famous for paying premium prices for things they really want — it’s an integral component of Galapagos logic. When Dyson introduces new models, they launch them in Japan first.

Dyson became the aspirational model for vacuum cleaners in Japan, in much the same way that the iPhone, which is also more expensive here than it is in other countries, became the cellphone of choice after an initial period of slow sales, partially supplanting local Galapagos keitai (which are still popular, by the way), and paving the way for smartphones. Japanese appliance makers try to make their vacuum cleaners look like Dyson’s and offer similar features. Dyson was the first vacuum cleaner that did away with paper packs, which was a means for manufacturers to earn revenue from their devices even after the sale. Now, paper packs are a memory.

In fact, there is a vacuum cleaner war in Japan, mainly between Dyson and another foreign manufacturer, iRobot, which makes the hockey puck-shaped Roomba autonomous cleaner. In 2014, Dyson launched its own robot cleaner, 360 Eye, again, in Japan first because this country had the highest market penetration.

A case could be made that robot cleaners have helped transform the Japanese home, which traditionally tended to be cramped and cluttered. In order for a Roomba to work, the floor has to be relatively free of stuff, and people cleaned up before they used them. Here were foreign manufacturers who not only carved their own Galapagos niche in the Japanese market, but did so by challenging a specific local norm. So if Japanese people really turned inward during the Heisei Era, some outside players figured out how to follow them there.

As Kawaguchi believes, Japan has always been Galapagos — and still is to a certain extent — but it has little to do with the kind of industrial chauvinism touted by Hosokawa or the right wing’s idealized and unadulterated idea of Japanese culture, which only exists in its imagination. Japan’s refusal to embrace a worldwide interest in the sharing economy as epitomized by Uber and AirBnB is just plain old-fashioned protectionism, pushed by specific economic interests, not cultural ones. Other countries do the same thing and Japan is part of this world, whether it likes it or not.