SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 2

Hangover

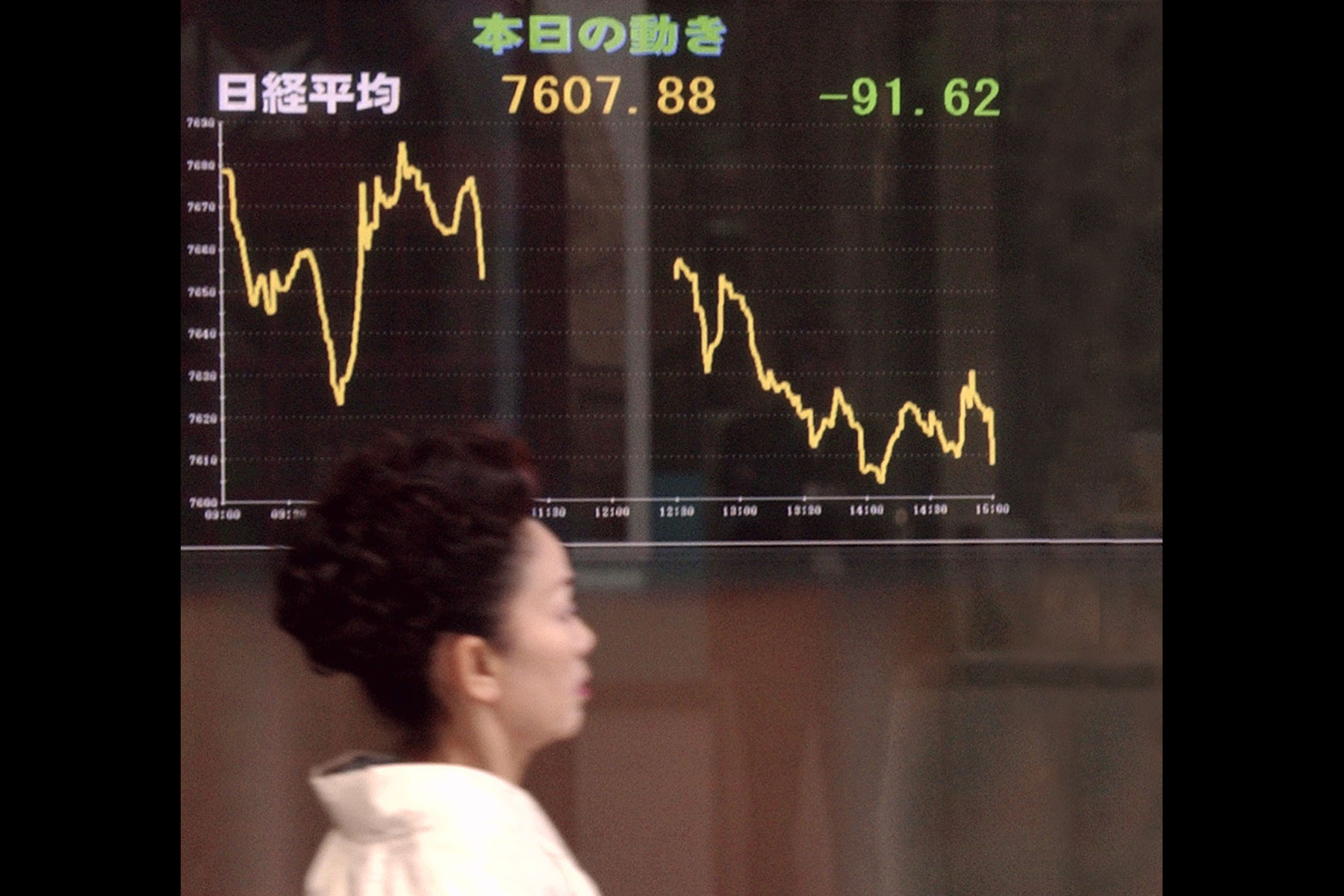

Lost confidence: A woman walks past an electronic stockboard in Tokyo's Yurakucho district that shows the Nikkei index ending trade at 7,607.88 on April 28, 2003. | KYODO

The second installment of a monthly 12-part series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades

ALEX K.T. MARTIN

Staff writer

Living out of the capital’s ubiquitous 24-hour internet cafes and capsule hotels, Sachihiko Kawamata is plotting a comeback.

The 70-year-old who provided accommodations to millions of Japanese no longer has a place to call home. Once lauded as one of the nation’s wealthiest men, Kawamata has seen his real estate empire whittled down to oblivion in the years following the burst of the economic bubble.

He filed for bankruptcy in 2009 after nearly two decades of endless calls from debt collectors. His family deserted him shortly afterward, and over the past 10 years he suffered two strokes, one heart attack and a life-threatening accident when he fell off a cliff while operating a bulldozer, leaving a noticeable dent in his forehead.

These days Kawamata usually heads to Okachimachi, a working-class shopping and entertainment district in northeastern Tokyo, to find affordable lodgings in the form of fake leather armchairs and narrow mattresses. It’s a taxing lifestyle for a pensioner, but Kawamata claims he has never felt this relieved. He doesn’t need to worry about keeping his company afloat and meeting debt payments. He only needs to concentrate on his next project, which he believes can help alleviate some of the myriad socio-economic problems Japan has been saddled with since entering the Heisei Era — a period that began with the popping of one of the world’s biggest stock market bubbles in history.

The cataclysmic event ushered in what economists describe as the lost 10 or 20 years when the nation saw plummeting property values, persistent deflation, declining and stagnant GDP, rising unemployment and the unprecedented aging and graying of the population that still gnaws at the country like a bad hangover.

At least Kawamata — a short, unassuming man with an affable smile — seems to have found peace.

“I know I may appear to be a sorry old man who lost everything and has nowhere to go,” he says. “But I’ve never been happier in my life.”

Kawamata’s assets totaled ¥300 billion at the height of the bubble. The Feb. 6, 1988, issue of the weekly Shukan Gendai magazine lists him as one of Japan’s 63 richest people, ranking him above legendary business leaders such as Masatoshi Ito, founder and honorary chairman of Japan’s biggest retail group, Seven & I Holdings, and Isao Nakauchi, founder of Daiei Inc., one of the nation’s largest supermarket chains.

Much of this was a mirage, of course — an illusion of affluence built on financial deregulation, monetary easing and excess liquidity in the banking system combined with robust domestic demand that led to aggressive speculation in real estate and the stock market.

Kawamata, who is credited for introducing short-stay apartments to Japan under the moniker “Tsukasa’s Weekly Mansion” (Tsukasa being a name derived from a cheap brand of shōchū — a type of distilled liquor — his mother used to serve at her yakitori restaurant in Tokyo before the family ventured into property), got his first taste of the era’s free-lending fervor in the mid-1980s.

A branch of the then-Mitsubishi Trust and Banking Corp. offered to loan him ¥960 million to purchase a planned 92-room apartment in Minato Ward’s pricey Shirokane neighborhood. Incredulous but encouraged by the exuberant vibes of the times, he signed the contract. Once the building’s construction was completed the following year, the property’s value had doubled to ¥1.8 billion.

By the time the Nikkei stock average hit a record-high 38,916 in December 1989, Kawamata had 180 employees operating 47 apartments and 4,000 rooms for rent in and around Tokyo. He owed more than 50 banks a whopping ¥150 billion despite his business churning out ¥6 billion in annual sales.

So when the government moved to rein in the craze, Kawamata was in trouble.

The Bank of Japan began raising interest rates sharply and the Finance Ministry issued limits on real estate-related lending, a combination of moves that saw the stock market tilt and then spiral into a nauseating fall. This was soon followed by a slump in property prices that jolted Japan’s three-decade “economic miracle” to a halt.

Over-generous banks were now left with piles of bad loans. Panicking, the lenders began summoning Kawamata, scrutinizing him over repayments. With what his company was earning, he could only come up with a small portion of the principal and interest he owed.

“At least we had a steady source of income to keep us limping forward,” Kawamata says. “Other real estate companies that borrowed far greater amounts went down like flies since they depended on selling property for profit. When they could no longer sell, they had no choice but to go belly up.”

The carnage extended far beyond realtors since firms used land as collateral for business loans and banks also held a significant amount of stock. When one side toppled, the other side reeled.

Data from Tokyo Shoko Research shows the number of annual corporate bankruptcies climbed from 7,234 in 1989 to 14,069 in 1992, by which time asset prices had visibly sunk. Total liabilities from defaults during the same period skyrocketed to ¥7.6 trillion from ¥1.23 trillion, a figure that would continue to balloon over the following years.

These developments took an obvious toll on consumer confidence and weighed on spending, which took a further hit when the government raised the consumption tax from 3 percent to 5 percent in 1997, miring the nation into a deflationary spiral it would struggle to shake off for the next two decades.

Scrambling to restore demand, the government ran massive budget deficits to fund various fiscal and economic stimulus measures. It invested more than ¥100 trillion in public works projects throughout the 1990s, but economists generally agree that these efforts were temporary remedies that ultimately proved futile.

Corporations were also forced to cut costs, but Japan’s lifetime employment system saw employers stuck with surplus staff they couldn’t fire.

What followed is known as the “hiring ice age,” a period generally considered to have lasted from 1993 to 2005, when strapped companies slashed recruitment and many young university and high school graduates found themselves in insecure jobs as part-timers, contract workers and temporary staff.

Sixty-four firms rejected Yuki Yoshida, a 37-year-old freelance writer and author of books on urban legends and unsolved mysteries, when he graduated from the prestigious Waseda University in 2002.

Another 20 or so companies turned him down the following year, upon which he gave up on a full-time white-collar job and decided to pursue his current vocation.

“At the time I felt I must be a social varmint for not landing a job despite the enormous amount of effort I put in,” he says. “In retrospect, that experience was a catalyst that led me to make a living writing about unconventional topics like the occult. I’d like to tell everyone who may be in a similar situation now to stop blaming themselves like I did, because it really doesn’t have anything to do with your skill set.”

It took several years after the bubble’s burst, however, for the full impact of the crisis to surface.

Kawamata had somehow survived the asset price and stock market crash with his business intact. The Tsukasa brand was well-known by then, thanks to a series of television commercials starring a bespectacled Kawamata. The short advertisements featured a catchy, if not borderline annoying, jingle that many Tokyoites can still recognize and hum along with today.

However, things began looking murkier in the mid-1990s starting with the collapse of several regional banks. A sense of panic began to set in after Sanyo Securities defaulted in November 1997, immediately followed by the fall of the Hokkaido Takushoku Bank and Yamaichi Securities, the latter at the time being Japan’s No. 4 brokerage with a century-old history.

A dozen more banks and security firms shut down by 1999, culminating in a full-blown systemic crisis.

In many cases, these financial institutions had failed to improve their balance sheets that had been damaged over the years by excessive investments in real estate or stocks during the bubble era.

The flurry of bankruptcies and the tens of thousands of jobs lost also signaled a new period in Japanese business governed by market forces and all its side effects, including reduced job security and wider income and wealth disparities.

The situation posed a dire threat for Kawamata, who had been repaying his debt incrementally but still owed around ¥80 billion.

“When all those banks crashed in 1999, I thought I was done for,” he recalls. “However, I always seemed to be saved at the last minute.”

To the rescue came the Lehman Brothers, the fourth-largest investment bank in the United States whose downfall a decade later played a prominent role in the global financial crisis.

Lehman offered to shoulder Kawamata’s debt in return for taking over operations of his short-stay apartment business. That left Kawamata with around 30 employees and 10 apartment buildings he leased out as small offices.

Kawamata’s enterprise shrunk considerably, but he had somehow dodged another crisis.

Kenji Yumoto, vice chairman of the Japan Research Institute, says the impact of the bubble’s burst reverberated throughout much of the Heisei Era, a period that began in 1989 and is slated to come to a close on April 30, 2019.

“The magnitude of the collapse of the bubble economy was so incredible that Japan’s unique employment, management and financial systems no longer became sustainable. That breakdown and the adjustments it forced created an enormous amount of pain,” he says.

That meant simply settling bad loans wouldn’t bring an end to Japan’s malaise, he says.

When Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, known for his unruly mane of hair and love of Elvis Presley, came to power in 2001, the economy was — pun intended — “all shook up.” The financial system was in shambles and large banks were hamstrung by bad loans.

Koizumi promised economic recovery based on an overhaul of banks and wide-ranging administrative reforms that included the privatization of postal services. He tasked prominent economist Heizo Takenaka, whom he appointed as financial services minister, to push debt-laden lenders to write off trillions of yen in bad loans and unload their huge stock portfolios.

By April 2003, the Nikkei had sunk to 20-year lows of 7,607.88, but gradually began to climb as the economy showed signs of bottoming out. Domestic demand recovered and exports picked up with the weaker yen and strong appetite from the United States, China and Europe, bringing with it a period of modest economic growth.

The numbers, however, belied a darker societal change that was taking place in Japan — the emergence of poverty.

Makoto Yuasa, one of Japan’s most famous social activists, has been supporting the homeless in Tokyo since 1995.

Back then most Japanese had little sympathy for these people, he says, regarding their plight as a result of laziness.

Since emerging as an industrial powerhouse in the 1960s and ’70s, Japan had been proud of what it considered a nation of middle-class citizens. The jobless and homeless represented an embarrassment it could not tolerate, a sentiment that persisted even in the years following the bubble’s burst.

But as the 1990s wore off, Yuasa began detecting a disturbing trend. The number of homeless people he found living on the streets of Shibuya, one of the city’s busiest neighborhoods, soared from around 100 in 1995 to 600 in 1999.

“It was happening everywhere in the nation,” he recalls. “It felt like the bottom was falling out of this world.”

Following the turn of the millennium, media coverage of the widening wealth gap grew as the nation embraced a more open style of capitalism under Koizumi that also saw a rapidly growing number of lowly paid temporary laborers prone to job cuts.

The term “working poor” entered the lexicon when NHK aired a documentary in 2006. In the same year, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development said in a report that the rate of relative poverty in Japan was one of the highest among its member nations. Internet cafes became temporary shelters for the hordes of laid off workers who would otherwise find themselves homeless, coining the phrase, “net cafe refugee.”

The issue reached a boiling point when Yuasa led a group of unions and nonprofits to open a makeshift shelter on the last day of 2008. He set up hundreds of recently fired workers in tents in Tokyo’s Hibiya Park, across the street from the labor ministry in a demonstration that drew thousands of volunteers and widespread media coverage.

Finally, Japan seemed to accept poverty as a real threat.

These events helped bring a shift in attitude among policymakers, as well as the general public, Yuasa says.

“To put it simply, it marked a transition from a ‘help yourself’ mind-set to one of mutual aid,” he says.

Kawamata, for his part, understands the harrowing reality many of his fellow citizens faced. He has seen the tragic consequences of unemployment firsthand — a guest at one of his company’s rental apartment rooms jumped to his death from the rooftop of a building after failing to find a job.

The incident prompted him to conjure up an unusual plan, where he solicited employment applications from guests who used his internet-equipped, ¥1,500 per day “net rooms,” offering them work as cleaning staff for his company with the possibility of permanent employment.

He would never find out whether his project would bear fruit.

In September 2008, Lehman Brothers went down in the world’s largest bankruptcy filing in history, making it the biggest victim of the U.S. subprime mortgage-induced financial crisis that swept across the globe and took millions of jobs.

Takeshi Miyashita, 62, worked at the Tokyo office of the American investment banking and financial services firm Jefferies Group when the subprime meltdown cost him and most of his colleagues their posts.

Already in his 50s and with two children getting ready for college, Miyashita clambered to find his next gig, but it took him over six months before he landed a position in a little-known technology firm involving a significant pay cut.

“Those were tough times, to say the least,” he recalls.

Lehman’s demise brought a swift and decisive end to Kawamata’s business. He and his company simultaneously declared bankruptcies totaling ¥162 billion. When all legal proceedings concluded in 2010, he was penniless and back on his own. His wife and two children had left him.

What he did have, however, was fame. Over the years he had published several books chronicling his tumultuous career and his thoughts on the economy. People still easily recognized the Tsukasa brand as well as its charismatic president, and his expertise was sought after.

Kawamata quickly embarked on a new project to revitalize Inawashiro, a graying town in Fukushima Prefecture suffering from depopulation, a typical case of the demographic dilemma the nation harbored as its birth rate fell and its citizens aged.

He offered room and board for the young volunteers who gathered from around the country to offer their help. And while he suffered severe injuries that year from the bulldozer accident, things appeared to be on track — until March 11, 2011, when a magnitude 9 earthquake set off massive tsunami that crashed into hundreds of kilometers of the country’s northeastern coast and triggered meltdowns at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

The prefecture, and the rest of the nation, was immediately engulfed by a state of confusion as it rushed to deal with the unprecedented calamity.

“That was another direct hit. First it was the bubble’s burst, then the fall of the Lehman Brothers and, finally, the 2011 disaster,” Kawamata says. “I must say, it’s been a crazy life.”

It has been six years since Shinzo Abe returned to power and launched his Abenomics stimulus policies. The economy is growing, with unemployment down and the stock market enjoying a resurgence as corporations reap record profits.

But Kawamata is skeptical, saying the increasing interdependence of world economies means a financial crisis somewhere on the globe can quickly spread like wildfire. His doubts may be understandable, considering all he has seen.

He spends his days now working on his new project, a culmination of a lifetime of experiences. Promising a 12 percent annual return, he is seeking investors for what he calls the Tokyo Business Cabin, a complex that combines the functions of a shared office, internet cafe and capsule hotel with additional networking and recruitment services for those seeking business partners or employment.

Perhaps it’s a quixotic venture taking into account Kawamata’s health, age and resources. Ever the entrepreneur, however, he’s determined to ensure it is a success.

“It isn’t some far-fetched dream, it’s based on everything I’ve done in my life,” he says. “There are still numerous people who have nowhere to go — I know this firsthand. I want to create something that reflects these times.”

Talk of the times

Kakaku hakai (価格破壊): A term that describes a sudden, widespread drop in prices.

Shūshoku hyōgaki (就職氷河期): A term used to describe the “ice age” in the job market.

Kashi shiburi (貸し渋り): Credit crunch

Kashi hagashi (貸し剥がし): The withdrawal of loan credit

Kakusa shakai (格差社会): Literally “disparate society,” this term was used to describe the widening income inequality that prevailed following the bursting of the bubble economy.

Haken giri (派遣切り): To downsize by laying off part-time or temporary staff.

Ushinawareta jūnen (失われた10年): Literally the “lost decade” — the period of economic stagnation that followed the bursting of the economic bubble.

Netto kafe nanmin (ネットカフェ難民): Net cafe refugee. A term used to describe a class of homeless people who live in internet cafes.