SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 11

Insecurity

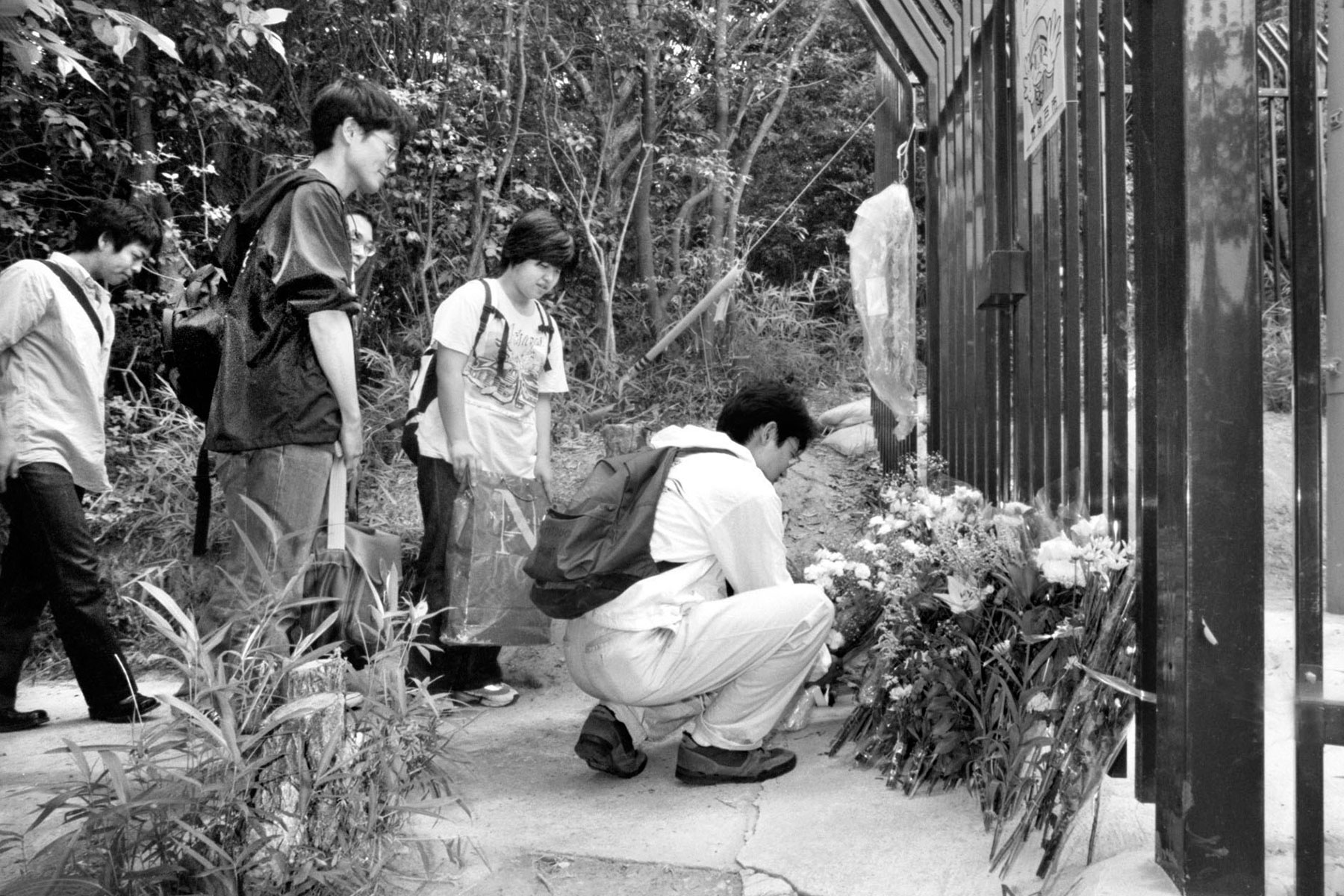

Coming together: Good Samaritans deliver relief supplies to survivors of the Great Hanshin Earthquake days after the magnitude 7.3 temblor struck the Kansai region on Jan. 17, 1995. The disaster killed more than 6,000 people and caused catastrophic damage to infrastructure, including the collapse of portions of elevated railway lines. | KYODO

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the 11th installment of a series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades. This contribution examines the shifting perception of safety over the past 30 years

ALEX MARTIN

Staff writer

Post-disaster Tohoku has been rife with supernatural sightings.

Hauntings have been reported at homes and workplaces, in ruined towns and on beaches devastated by giant tsunami that crashed into hundreds of kilometers of Japan’s northeastern coast on March 11, 2011, following a magnitude 9 earthquake that left more than 15,000 people dead and thousands missing.

Among the numerous tales, those recounted by taxi drivers in the city of Ishinomaki, one of the hardest hit areas in Miyagi Prefecture, have struck a nerve due to their chilling realism.

One driver swears that a woman in her 30s wearing a fur coat ordered him to take her to a coastal area pummeled by the tsunami on a summer night, only to ask him whether she was dead before disappearing into thin air.

Then there was an elementary school-aged girl, also dressed too warm for the season, who asked another driver to take her home. When the cab reached its destination, she thanked the driver who went to help her out of the car before realizing she had vanished.

In both cases, the taxis’ meters were running and the drivers clearly remember chatting with their passengers. They say they weren’t scared but awestruck by the experience, adding that they’d be willing to serve their ghostly customers again if they ever flagged them down.

Some might argue that such encounters are a reflection of uncontainable despair, a paranormal manifestation of collective sorrow that helps us cope with a lingering sense of loss. The accounts were gathered by Tohoku Gakuin University student Yuka Kudo for her graduation thesis and later published as part of a book titled “Reisei no Shinsaigaku,” which translates along the lines of “Spirtualism and the Study of Disaster.” It was edited by Kiyoshi Kanebishi, a sociology professor at the institution who oversaw the fieldwork, and its tales of cab-hailing spooks quickly went viral and were widely cited in the media as examples of how residents were coping with a tragedy of unprecedented scale. The disaster, and others like it, contributed to what felt like an ever-present threat to safety during the Heisei Era.

When the quake hits

The abdication of Emperor Akihito on April 30 will mark an end to a tumultuous three decades sometimes referred to as the “era of natural disasters.” The past 30 years saw the eruption of Mount Unzen’s Fugen peak in 1991 and two major earthquakes — the Great Hanshin Earthquake of 1995 that destroyed the city of Kobe and the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011, which triggered deadly tsunami and the most frightening nuclear crisis since Chernobyl in 1986. In addition to those events came the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system in 1995 — the worst act of terrorism in modern Japanese history — and several notorious crimes involving serial killers and mass murderers.

“Call it my imagination, but when I contemplate the meaning of the end of the Heisei Era, I’m drawn toward the idea that it’s about putting to rest a period of disasters and starting fresh,” Kanebishi says.

The 43-year-old sociology professor experienced both the 1995 and 2011 quakes, which led him to coordinate a series of projects with his students examining how survivors of natural disasters adapt to loss over time.

Prior to the Meiji Restoration of 1868, when era names were formalized and designated to a single reign, emperors frequently changed them, often after natural disasters and other inauspicious events. For example, Emperor Komei, the predecessor to the Meiji Emperor and the current Emperor’s great-great-grandfather, oversaw seven era names during his time on the throne.

“I know the Emperor is abdicating because of old age,” Kanebishi says, “but perhaps he also has in mind that bit of history.”

Kanebishi was 19 and living with his parents on the border between Hyogo and Osaka prefectures, caught up in studying for his college entrance exam, when a magnitude 7.3 earthquake struck the Kansai region on Jan. 17, 1995. At 5:46 a.m., his house began to rock violently, and the concrete wall surrounding the house next door was knocked down.

His aunt’s home in Kobe was closer to the epicenter and was utterly demolished. Kanebishi was lucky in that no one in his family was killed, though the catastrophe would eventually claim 6,434 lives.

“We were glued to the television for days,” he recalls. “The test center was in one of the hardest hit areas, and I remember cowering from aftershocks while taking the exam. Watching aerial footage of the mess also made me wonder how ordinary folks were dealing with the situation, teaching me the importance of an eye-level approach to disasters.”

An erosion of security

While the wider Kansai area was still reeling from the aftermath of the giant quake, Tokyo was thrown into a state of chaos on March 20 when a series of chemical attacks on the city’s subway system left 13 people dead and injured around 6,300.

Masterminded by Shoko Asahara, the hirsute former acupuncturist who led the Aum Shinrikyo cult, the sarin gas attacks resulted in widespread police raids and the arrests of hundreds of the cult’s members. Nonstop media coverage of the incident gradually began to erode postwar Japan’s long-held sense of security, sending politicians, academics and counterterrorism experts scrambling to make sense of the new threat posed by religious extremism.

Following the attacks, Japan implemented stronger surveillance measures — security cameras were installed at train and subway stations, and trash cans were removed and redesigned to feature transparent panels that would allow you to see their contents. The Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States only heightened the notion that danger was imminent, and Japan responded with public ad campaigns imploring citizens to be on guard for suspicious people and objects.

Meanwhile, Asahara was found guilty in 13 different indictments that claimed a total of 27 lives and was sentenced to death in 2004. As many as 191 other Aum members were found guilty of crimes including murder, attempted murder, abduction, and the production of nerve gas and automatic rifles.

Last year, all 13 cult members on death row, including Asahara, were hanged, bringing both a sense of closure and disappointment to Aum’s victims while rekindling a national debate on capital punishment.

At a news conference following Asahara’s execution, Shizue Takahashi, whose husband was killed in the subway attacks, lamented that those who met their end on the gallows could have shed more light on the cult’s operations.

“There are many things I wanted them to talk about so we can learn more about future counterterrorism,” she said. “I really wanted them to speak to some experts.”

Those who were a part of the cult were similarly perplexed at the timing and scale of the executions.

“The executions of condemned Aum inmates may have been inevitable in terms of societal trends in Japan, but I still think carrying them all out in July was extreme,” says Orie Miyama, a 58-year-old former Aum member who now uses a pseudonym to protect her privacy.

While the hangings may reflect the Justice Ministry’s efforts to be sensitive toward Aum’s victims and a broader public desire for an appropriate punishment, critics have said they also sealed any possibility of uncovering the truth behind the cult’s atrocities, leaving many questions unanswered. During his trial, Asahara never explained his motives for the crimes, baffling the court with confusing comments and rants that caused some to doubt his sanity.

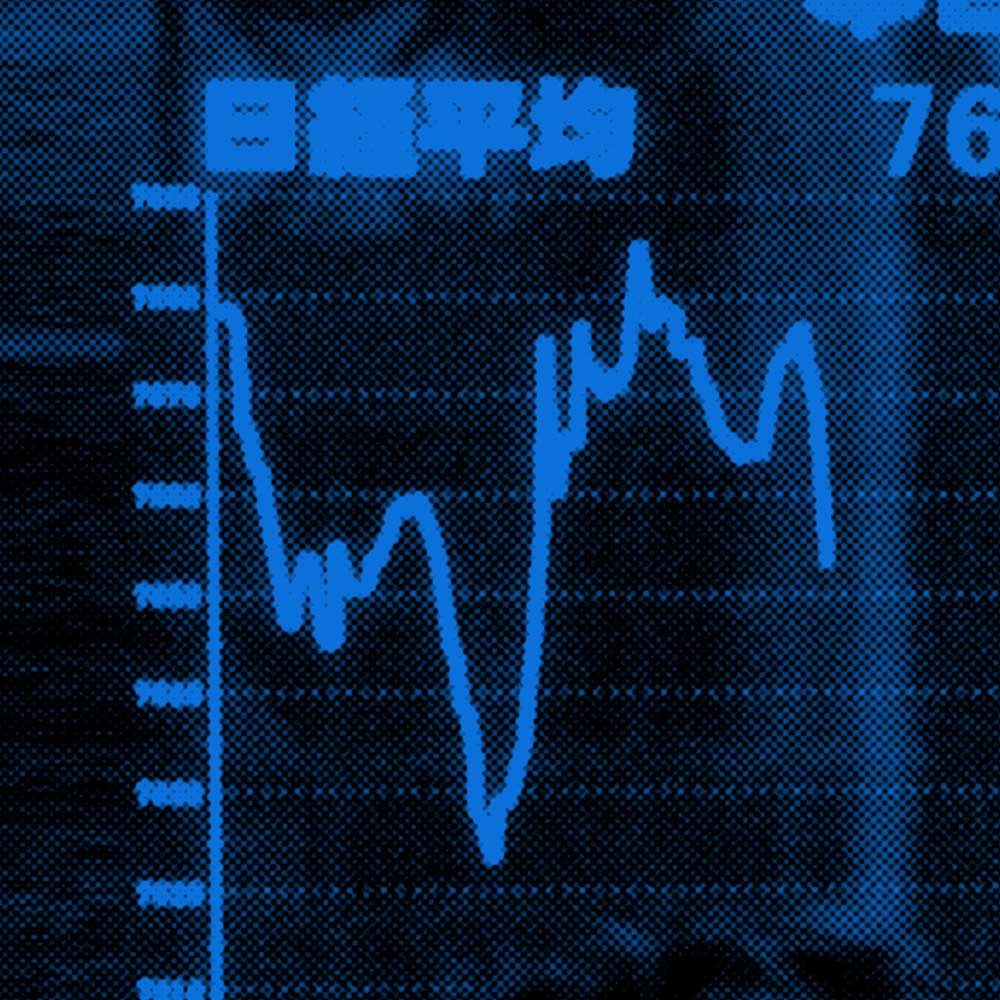

Miyama and her husband, Takenori Hayasaka, joined the cult in the late 1980s and were among the droves of young Japanese who felt alienated by the consumerist ethos fueled by the bubble economy of the time.

While the couple say they found peace in the Buddhist- and Hindu-influenced teachings espoused by Asahara, they would spend years coming to terms with the atrocities the cult committed. Since leaving more than two decades ago, the couple has been living quietly in Kanagawa Prefecture, hiding their involvement in Aum and working part-time jobs.

“There’s a certain level of difficulty and inconvenience living in this society as a former Aum member, and I know there are no small number of people who are suffering from their past affiliations,” says Hayasaka, who also goes by an alias. “The most I could ask for since leaving Aum has been to be able to live undisturbed.”

Murder most foul

Most of those who followed Shoko Asahara aren’t monsters but regular people who were searching for meaning in life,” says Takayuki Harada, a clinical and criminal psychologist, and professor at the University of Tsukuba. He interviewed Aum members who were behind bars but not on death row while working for the Justice Ministry.

“Asahara is an anomaly,” he says, adding that the Aum guru displayed the typical traits of a psychopath: He was manipulative, charismatic and without remorse. Unfortunately, one person can have an impact on many others.”

Another killer who sent a collective chill down spines during the Heisei Era was Seito Sakakibara, which is a pseudonym for a teenage serial killer jailed for some of the most gruesome murders in modern Japanese history.

In May 1997, the then-14-year-old Sakakibara strangled and decapitated an 11-year-old boy, placing his head in front of a junior high school gate in Kobe. He later confessed to the murder of a 10-year-old girl, as well as assaults on three other girls in a series of attacks that triggered calls for harsher punishment for underage offenders. The Juvenile Law was stiffened in response, in what would become a trend toward tighter control by authorities during Heisei.

In 2008, 25-year-old Tomohiro Kato drove a rented Isuzu truck into a crowd in Tokyo’s Akihabara district, killing three people and injuring two before embarking on a stabbing rampage that killed an additional four people and injured eight before being stopped by police. The so-called pedestrian paradise in Akihabara was suspended for a few years following the murders while the government revised laws in order to ban the possession of daggers and other double-edged knives with blades of 5.5 centimeters or longer.

It was on July 26, 2016, when 26-year-old Satoshi Uematsu committed the worst single-murder killing spree since the end of World War II at a care home for people with intellectual disabilities in Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture. He stabbed 19 patients to death and injured 26 others, later telling authorities that he thought people with disabilities should “disappear.” The case prompted the government to review its mental health system.

And in 2017, 27-year-old Takahiro Shiraishi killed and dismembered nine people, eight of them young women whom he also sexually assaulted, at his apartment in Zama, Kanagawa Prefecture. Shiraishi used the social media platform Twitter to contact suicidal women, luring them in by offering to help them fulfill their suicidal requests. As was the case with previous mass murders, the incident ignited debate on stricter regulations, this time with regards to social networking services.

“These sensational events have led to tougher laws and more control,” Harada says. “Despite the media frenzies, though, the crime rate in Japan has been falling for some time. The amount of attention these occasional cases get may reflect how the nation is becoming safer than ever.”

The number of recorded crimes fell to 817,338 last year, the lowest level in the postwar era, according to the National Police Agency. As the nation ages, however, it’s interesting to note that the proportion of crimes committed by those over 65 has been steadily on the rise for the past 20 years.

According to Harada, one common thread running through these gruesome murders is a growing sense of alienation and an erosion of interpersonal relationships.

“While most murder victims are killed by people they know, such as family members or lovers, that’s not the case with the Zama and Sagamihara murders, and that seeming randomness scares people into thinking they could be next,” he says.

The business of security

The fear instilled by sensationalist coverage of serial killers, mass murderers and stalkers seems to be fueling the success of a handful of home security firms.

Secom Co., which was established in 1962 and is now Japan’s largest home and office security company, has seen its security contracts soar over the past few decades and now boasts 1.28 million household and more than 1.04 million corporate clients.

“Our services aren’t limited to homes and buildings but include moving things such as cars and people,” says Hiroaki Ibumi, head of Secom’s corporate communications department.

“The number of crimes may be in decline, but there’s been an increase in demand for monitoring services for children and the elderly,” he says, citing worried parents and the prevalence of kodokushi, or “lonely deaths,” where senior citizens living alone are found dead at home after going unnoticed for days or even weeks.

Technological advancements have allowed companies like Secom to take advantage of demographic trends by offering innovative gadgets. For example, in 2017 Secom began marketing a wearable device called My Doctor Watch, which can detect trouble and issue an emergency notification calling for assistance even if the wearer becomes unconscious.

Japan’s vulnerability to natural disasters has also helped the company’s emergency preparedness business gain traction, with its safety confirmation service now adopted by 7,000 firms covering 6.2 million employees.

“With so many earthquakes, there’s been a surge in demand from corporations concerned about business continuity management,” Ibumi says.

A spiritual transformation

Earthquake resistance was the primary factor that Tohoku Gakuen’s Kanebishi took into account when looking for a place to live after moving to Sendai in 2005.

Having lived through one major quake and relocating to an area historically prone to them, he bought an apartment in a building that was equipped with shock absorbers designed to dissipate kinetic energy. However, no amount of preparation would ready him for what came at 2:46 p.m. on March 11, 2011.

While his apartment largely withstood the powerful convulsions that lasted for several minutes, with only books and plates falling from their shelves, he was eventually stranded without electricity.

“I found out about the tsunami through radio broadcasts but wasn’t aware of the extent of the damage for some time,” he recalls.

After a week or so, Kanebishi began contacting his students at Tohoku Gakuin and instructed them to record everything they experienced after the quake.

“I knew from the Hanshin earthquake that it was important to gather the small details, which could easily be obscured or forgotten,” he says

The students were later mobilized to collect personal accounts from survivors of the disaster spanning the three prefectures that were most affected: Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima. Compiled into a book that was published in 2012, their efforts to give voices to those who would have otherwise struggled to express themselves under the weight of the tragedy were met with universal praise.

“It was from that time that we began to focus on selecting a theme to explore every year, through fieldwork and interviews,” Kanebishi says. “These themes have so far included ‘letters to the dead,’ ‘dreams’ and, currently, one on those who remain missing.

“Academics tend to look at subjects from their own vantage point and have difficulty incorporating outside views, whereas students tackle their subjects with a clear and open mind. As with the case of ghost sightings, I’ve been continuously surprised by my students’ capabilities to discover new angles.”

Drawing a comparison to the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, which had a long-lasting impact on European religion, philosophy and seismology, Kanebishi suspects the triple disaster in Tohoku may have triggered a spiritual transformation that transcends the physical damage and death tolls, and is an area that requires further exploration.

In a disaster-prone nation, what we can learn from these calamities could be of great significance for when the next crisis hits.

“I’ve experienced two major earthquakes so far,” Kanebishi says. “If I live for another, say, 60 years, I wouldn’t be surprised if I were to experience two or three more.”