SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 10

Solidarity

On their own: Commuters stand in a women-only carriage of a train car on the Higashiyama Subway Line at Nagoya Station in 2002. The subway line was the first of its kind to begin operating such a service as a way to deal with the problem of groping by men on train carriages. Critics argue that women-only carriages are not a real solution. | KYODO

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the 10th installment of a series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades. This installment examines the shifting state of women in society

MASAMI ITO

Contributing writer

Last April, a female reporter from TV Asahi accused Junichi Fukuda, the top bureaucrat at the Finance Ministry, of sexual harassment.

The woman recorded the conversation, excerpts of which were later published by weekly magazine Shukan Shincho.

The magazine also released an edited audio clip said to be of Fukuda telling the woman: “Can I touch your breast?” “Should we have an affair when the budget is enacted?” and “I will tie your hands.”

Fukuda initially denied the allegations but resigned after other media outlets jumped on the story and his position became untenable.

The above case is just one example of increasing efforts being made by women in Japan to speak out against sexual harassment and violence.

Such conduct was certainly rare at the start of the Heisei Era 30 years ago, when there was much less public conversation about such issues in society. Although times have changed, the Emperor will abdicate the throne in April and yet, as things stand, his granddaughter has been barred from ever sitting on the throne. With this in mind, it’s worth examining whether the state of women in Japan has changed significantly over the past three decades — if at all.

Speaking out

Journalist Shiori Ito has spoken out publicly against sexual violence, doing so about five months before the #MeToo movement started to gain traction overseas.

Ito appeared at a news conference at the end of May 2017 and accused journalist Noriyuki Yamaguchi of rape, asking members of the press to use her first name in their reports in order to protect the privacy of her family. She had previously filed a complaint with the police, but Yamaguchi has repeatedly denied the allegations and prosecutors have never formally charged him with anything.

People close to Ito had warned her that she would never be able to work in Japan again if she made the allegations public. However, Ito says she simply couldn’t remain silent.

“I had no other choice,” Ito says. “I had tried every other way but nothing had worked. I realized we really had to discuss (issues related to sexual violence against women) openly for a change. … I had to talk about it without hiding my face or my name because, otherwise, people can easily dismiss it.”

Almost immediately, people started to blame Ito for what had happened. Numerous men and women attacked her via email or on social media, suggesting that the alleged assault was more than likely the result of the way she was dressed, her behavior, the situation in which the reported incident took place and so forth.

In the end, Ito left Japan for London, where she has made a fresh start as a journalist.

In October 2017, the #MeToo movement began to spread virally on social media, but it took a little longer to start making waves in Japan.

“On the other side of the world, the #MeToo movement was being discussed in a different way,” Ito says. “There were so many women who were supporting each other and raising their voices together. I felt so alone.”

Scale of harassment

Although women in Japan didn’t embrace the #MeToo movement as quickly as their contemporaries in Europe and North America, they did eventually start to speak out.

At first, people were quick to blame the victims, but slowly, over time, a stronger sense of solidarity began to develop.

Immediately after the allegations against Fukuda came to light, online news website Business Insider Japan conducted a survey of around 120 women in the media industry and asked them whether or not they had encountered sexual harassment.

According to the responses, more than 80 percent had encountered some form of harassment, with as few as 30 percent talking to anyone about it.

Keiko Hamada, editor-in-chief of Business Insider Japan, says she was initially shocked that female reporters were still encountering so much harassment in the workplace, something that was common when she was in her 20s and 30s.

During a recent interview with The Japan Times, Hamada says she continues to feel guilty for not speaking up back then.

“We ignored what was happening,” Hamada says. “We pretended that nothing had happened because women who spoke out were viewed as an embarrassment. If we had called out sexual harassment — a word that was barely used back then — people would have considered us to be a nuisance and we would have been removed from the job.”

Equal opportunities

Hamada, 52, started working as a reporter for the Asahi Shimbun in 1989, the same year that the Heisei Era commenced.

It was also a year that featured other significant incidents related to women. The country’s first sexual harassment lawsuit was filed in 1989, while a couple filed an appeal to the Family Court after being denied separate surnames after marriage.

1989 was also the same year in which the country’s birth rate fell to an all-time low of just 1.57.

Just four years earlier, the government had passed the Equal Employment Opportunity Law, which aimed to eliminate discrimination based on gender.

Hamada is a member of the “equal opportunity law generation,” a group of women who finally, by law, had the same opportunities in the workplace as their male counterparts.

Starting her career as a reporter for the Asahi Shimbun, Hamada eventually became the first female editor-in-chief of the Asahi Shimbun Publications Inc.’s weekly magazine Aera.

Writing in a 2018 book titled “Working Woman and Sense of Guilt,” however, Hamada found that little changed after the legislation came into effect.

Hamada, like many other female jobseekers at the time, was asked the typical question of whether or not she would be able to continue in the position even if she were to get married or have children.

While the problematic nature of such an inquiry is obvious these days, it was a loaded question that was actually difficult to answer, as some companies wanted women to quit after a certain period of time so that they could hire younger female employees as replacements.

Female reporters were rare at the time and Hamada recalls standing out wherever she went. She struggled to fit in easily with her male colleagues, who would typically discuss sports when they went out drinking with interview subjects.

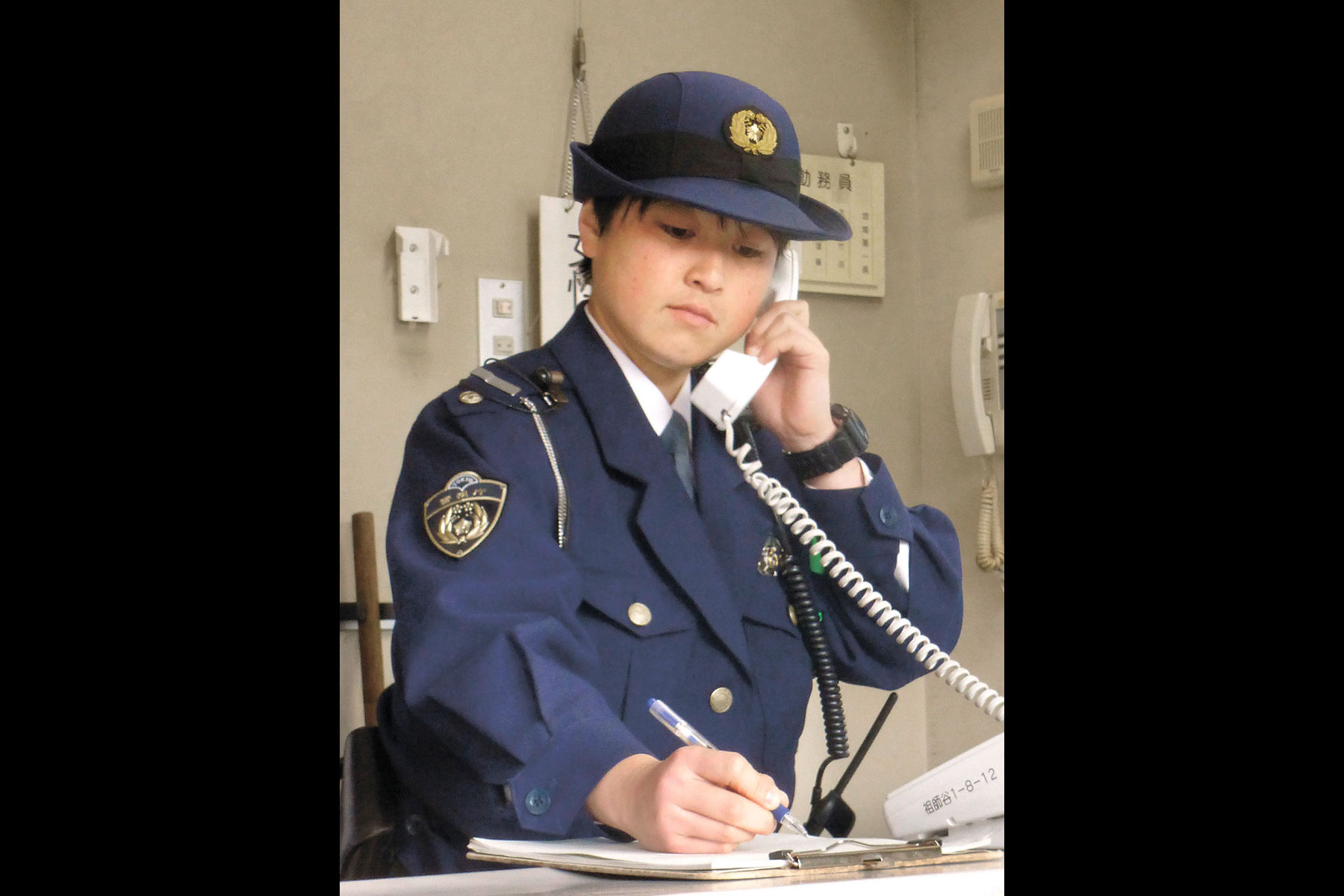

Readers would often ask to speak to “a reporter” when they phoned the newspaper, not realizing that the woman on the other end of the line could just as easily be a journalist.

If Hamada managed to prize information out of a source, her male colleagues and reporters from other companies would say such things as “women are lucky” in the background.

What’s more, Hamada struggled to feel comfortable in a variety of clothes. If she wore a skirt, her supervisor would scold her and, if she wore pants, the person she was interviewing would suggest she wear a skirt. She simply couldn’t win either way.

Hamada didn’t let it rattle her and, instead, tried to focus on her job.

“A male-oriented society had certain rules and, if you didn’t abide by them, you weren’t even allowed in the ring,” Hamada says. “Women were terrified of being kicked out of that male-oriented society.”

The number of working women increased from 53.1 percent in 1986 to 56.9 percent in 1992 as female workers benefited from the Equal Employment Opportunity Law and the surge in confidence brought on by the bubble economy.

However, the number of women in the workplace stagnated for about a decade from 1992 after the bubble burst and opportunities started to dry up.

“It was the lost decade, the ‘Dark Ages’ of the 1990s, and I almost felt that time had stopped,” Hamada says. “Looking back at the past 30 years, I think the state of women was deeply affected by the economy.”

Turning point

One year before the implementation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Law in 1986, Japan ratified the U.N. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

A decade later, in 1995, the Fourth World Conference on Women was held in Beijing, which experts agree was a turning point for women around the world, including Japan.

At the conference, 189 participating countries and territories worldwide endorsed the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, with U.S. first lady Hillary Clinton declaring that “women’s rights are human rights.”

Following the international conference, Japan enacted the Basic Law for Gender Equal Society in 1999, which aims to form a society in which “every citizen is able to fully display their individuality and ability regardless of gender.” The Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office described the law as “a new step engraved in the history” of building a gender-equal society.

But Tomomi Yamaguchi, an expert on gender studies at Montana State University, is not as enthusiastic, noting that the Japanese name of the law doesn’t even include “equality” or “discrimination.”

While the English translation of the law includes the word “equal,” a direct translation of the original Japanese would be to create a society based on “joint participation of men and women.”

Furthermore, the preamble of the legislation identifies Japan’s rapidly changing socioeconomic situation, including a “trend toward fewer children.” Yamaguchi specifically criticizes this, arguing that low birth rate measures have nothing to do with discrimination against women.

“The law should have been based more on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, with a stronger aspect to abolish gender discrimination,” Yamaguchi says. “It became extremely difficult to differentiate between gender equality and low birth rate policies.”

An expert on feminism and social movements, Yamaguchi says one major setback for women’s rights in Japan was the backlash against feminism in the early 2000s led by conservatives, including Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

In 2005, Abe headed a Liberal Demographic Party team to investigate “extreme sexual education and gender-free education.”

“It is necessary to take concrete measures to abolish gender discrimination … but, as a result of the backlash, the ‘joint participation of men and women’ under the leadership of the Abe administration has become a mere facade,” Yamaguchi says.

Female empowerment

In recent years, Abe has turned his attention to women in the workplace, promising to create “a society in which women can shine.”

As part of this pledge, the government enacted a law to promote the role of women in the workplace in 2015 and passed legislation to increase the number of female lawmakers in the national and local assemblies last year.

Promoting female empowerment, however, is proving to be much easier said than done.

Abe and his administration had initially wanted to increase the number of women in management positions to 30 percent across the board by 2020. In 2015, however, the government lowered the bar to more realistic targets, ensuring that women comprised 7 percent of management positions in government posts and 15 percent in companies.

As of April last year, female politicians in the Lower House accounted for 10.1 percent of total lawmakers and in the Upper House, 20.7 percent.

Meanwhile, the number of working women is on the rise. Working women totaled 29.46 million in 2018, an increase from the 26.64 million recorded in 2008. The employment rate for women aged between 15 and 64 has gone up significantly over the same period of time, rising from 59.8 percent in 2008 to 69.6 percent in 2018.

At the same time, however, the percentage of women who work irregular jobs is still high, comprising almost 70 percent of the total in 2018. Statistics from the same year show that 44.1 percent of female irregular employees made less than ¥1 million annually.

Looking specifically at regular employees, the highest 22.8 percent of men in 2018 made ¥5 million to ¥6.99 million annually, while the highest 28.1 percent of women made just ¥2 million to ¥2.99 million.

“Abe’s attempt to empower women is part of his economic policy, Abenomics, but has nothing to do with women’s human rights,” Yamaguchi says. “He’s focused on the limited number of women who can contribute to the economy.”

Support for women inside the family home also remains limited. According to data compiled by the Cabinet Office in 2016, women in households with children who are 5 years old or younger, spend 7.34 hours a day on household chores including child rearing. Men, on the other hand, spend 1.23 hours a day, the lowest number among developed countries. Women in the United States, for example, spend 5.4 hours a day on household chores, whereas men spend 3.1 hours.

It’s perhaps not surprising that Japan’s ranking on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report, which calculates the gap between men and women in health, education, economy and politics, is low every year.

In 2018, Japan ranked 110th out of 149 nations, placing Japan at the bottom of Group of Seven nations.

Making headway in Nagatacho

Japan still appears to be struggling to become a more gender-equal society, especially as far as national politics goes, but there have been a couple of times during the Heisei Era when female lawmakers made waves at the heart of Japanese politics in Nagatacho.

One of the most memorable of these times came in July 1989, when 22 female lawmakers won seats in the Upper House election, an achievement that was dubbed the “Madonna whirlwind.”

Then-Japan Socialist Party President Takako Doi, the first female leader of a major political party, delivered a strong blow to the ruling LDP at the time. Doi later became the first female speaker of the House of Representatives.

Hiroko Goto, a professor at Chiba University and an expert on gender issues, says having influential female politicians such as Doi helped push forward key measures to prevent violence against women that were eventually implemented during the early 2000s.

In 2000, the first anti-stalking law was enacted after a 21-year old female university was stabbed to death in 1999 after being stalked by a man she had dated. The man had stalked and harassed her, her family and her friends, but the police failed to take action.

In 2001, a domestic violence prevention law for the first time stipulated that physical spousal violence was a crime. The law was later revised in 2004, which expanded the definition of violence to include psychological abuse.

Goto says the enactment of legislation related to violence against women has been groundbreaking.

“Without equality inside a family, there is no social equality,” she says. “I believe that once we ensure equality inside families, it could lead to equality in society as well.”

In 2017, the country’s sex crime law was revised for the first time in 110 years to expand the acts that constitute rape. Previously limited to vaginal penetration by a penis, the new definition now includes forced anal and oral sex, meaning men can be rape victims. The minimum sentence in the legislation was raised from three years to five years imprisonment.

Experts, however, point out that a major obstacle in the law remains: In order to establish an assault as rape, a perpetrator must have used physical force or have threatened the victim. In many cases, however, victims are too terrified to resist.

Goto notes that the international trend has transitioned from “no means no” to “yes means yes.”

“The revision does not help women much in the sense that the law still requires an assault to involve force or a threat (of force),” Goto says. “It’s a completely outdated clause.”

Another unresolved issue pertains to surnames. By law, married Japanese couples must use the same family name and more than 95 percent of couples take the husband’s name. In the past 30 years, opportunities to revise the Civil Law have arisen but the legislation has yet to pass the Diet.

The U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women has also called on Japan to amend the law in order to enable women to retain their maiden names.

“The Heisei Era didn’t go as far as to overthrow patriarchy,” Goto says. “Japan has made some progress regarding violence against women but the family system and patriarchy, which shape the fundamental values of Japanese society, haven’t been defeated. This reality is symbolized by the existing state of the surname issue.”

Escaping the labels

In April, the Heisei Era will come to an end after 30 years.

Ito, who was born in 1989, will also turn 30 this year. Despite everything she has been through, Ito refuses to give in.

She has transitioned from being labeled a victim to becoming an international journalist.

Winning a couple of awards for her work, Ito co-founded a documentary production company with fellow journalist Hanna Aqvilin. Over the past 12 months or so, she has been flying around the world, working in locations such as the United States, Africa and Japan.

“I’m still affected by the labels people have given me but if I live my life, maybe the labels will keep changing,” Ito says. “The world is becoming more diverse and hopefully these labels won’t be so prevalent in the future. I hope the time will come when ‘me too’ is no longer needed as a phrase.”

That said, Ito believes there is still plenty of work that needs to be done before women can contribute to society on an equal footing.

“We can now talk about (sexual violence) and that’s a huge step, because we can’t really do anything about it without first knowing what’s going on,” she says. “I think we’re now at the starting line of discussing exactly what women need.”