SPECIAL HEISEI SERIES

Defining the Heisei Era: Part 1

Excess

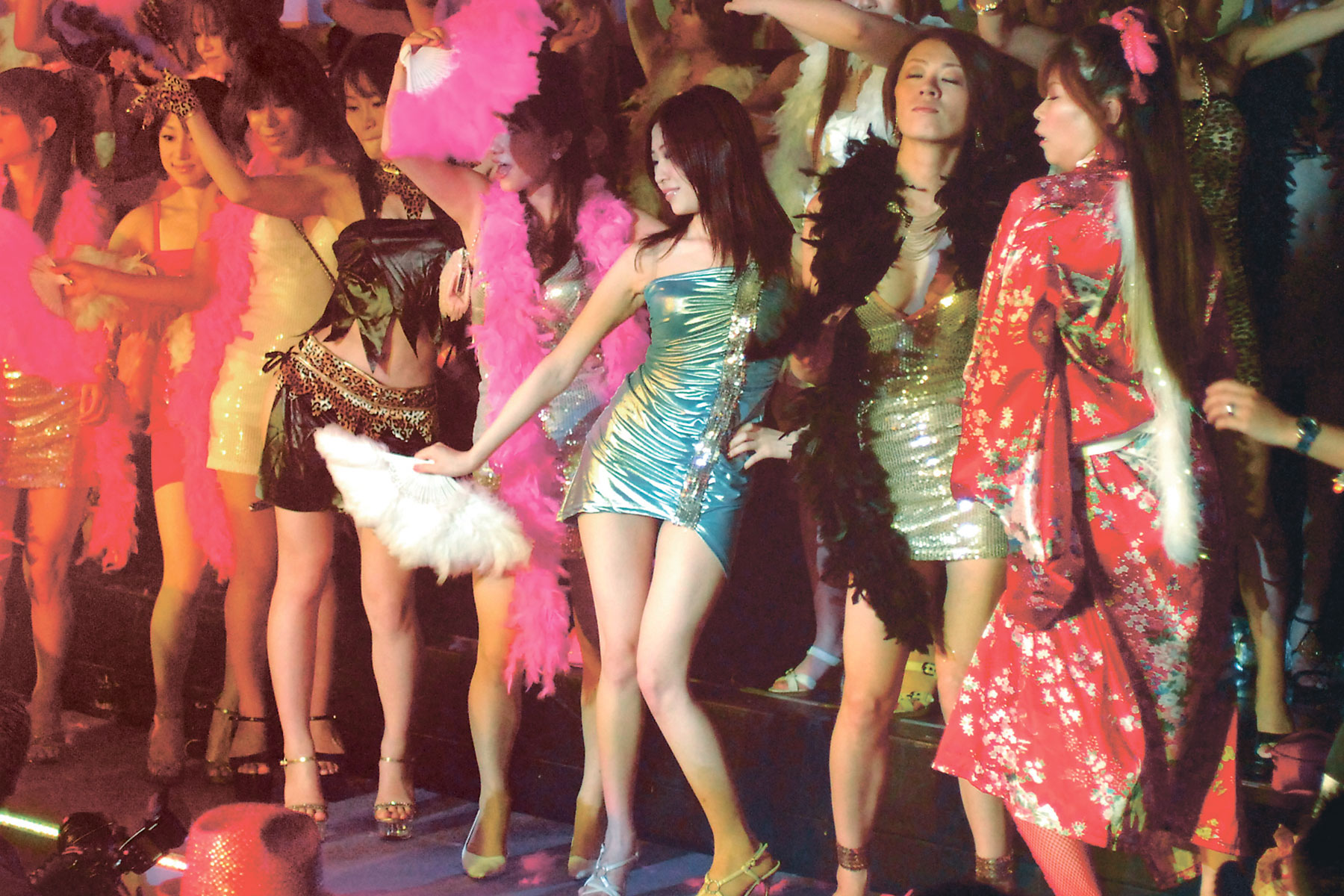

Women dance at Juliana's Tokyo in August 1994. | KYODO

As we count down to the end of the Heisei Era, The Japan Times presents the first installment of a monthly 12-part series that looks back at the leading issues of the past three decades

ROB GILHOOLY

Contributing writer

It’s Golden Week, 1991, and a line of hundreds of party-goers snakes its way along a rain-drenched street in a Tokyo bayside district toward the entrance of one of Japan’s biggest postwar nightlife sensations.

Among those braving the elements are men in turtleneck sweaters and baggy suits and their female fashion antitheses who are crammed into ultrashort, ultratight bodi-kon (a Japanese portmanteau of “body conscious”) dresses, their long, wan-ren (one length) hair unable to disguise enough bling-bling to start a metal works.

Some have traveled the length and breadth of the country to pirouette their pin-heels on the raised platforms and dance floors of what is an already near-mythical institution: Juliana’s Tokyo.

“I’ve been lining up for more than 50 minutes,” a woman who had traveled from Okayama to visit the discotheque, a joint venture between trading company Nissho Iwai Corp. and British gaming group, Wembley PLC, told me at the time.

“I came to Tokyo to dance here,” said another from Hiroshima, whose shoulder pads — another trend of the times — were struggling for shelter under her flowery umbrella.

Those times — the tail end of the Showa Era (1926-89) until the early part of the subsequent Heisei Era, which has been slated to end on April 30, 2019 — are commonly referred to as Japan’s “bubble era,” a relatively short-lived span of unsurpassed affluence that was packed with enough extravagance and revelry to make even Comus blush.

At its peak, which started around late 1985 following the signing of the Plaza Accord by Japan and five other nations in an attempt to depreciate a rampant U.S. dollar, businesspeople waved ¥10,000 bills to catch the eyes of overworked cabbies, and well-heeled women in Kyoto and Nara splashed almost 10 times that on a cup of coffee sprinkled not with cinnamon, but gold dust.

The 1-square-kilometer of land on which Tokyo’s Imperial Palace sits was reportedly worth more than Canada, while the value of Metropolitan Tokyo’s 620 square kilometers was estimated to exceed that of the entire United States.

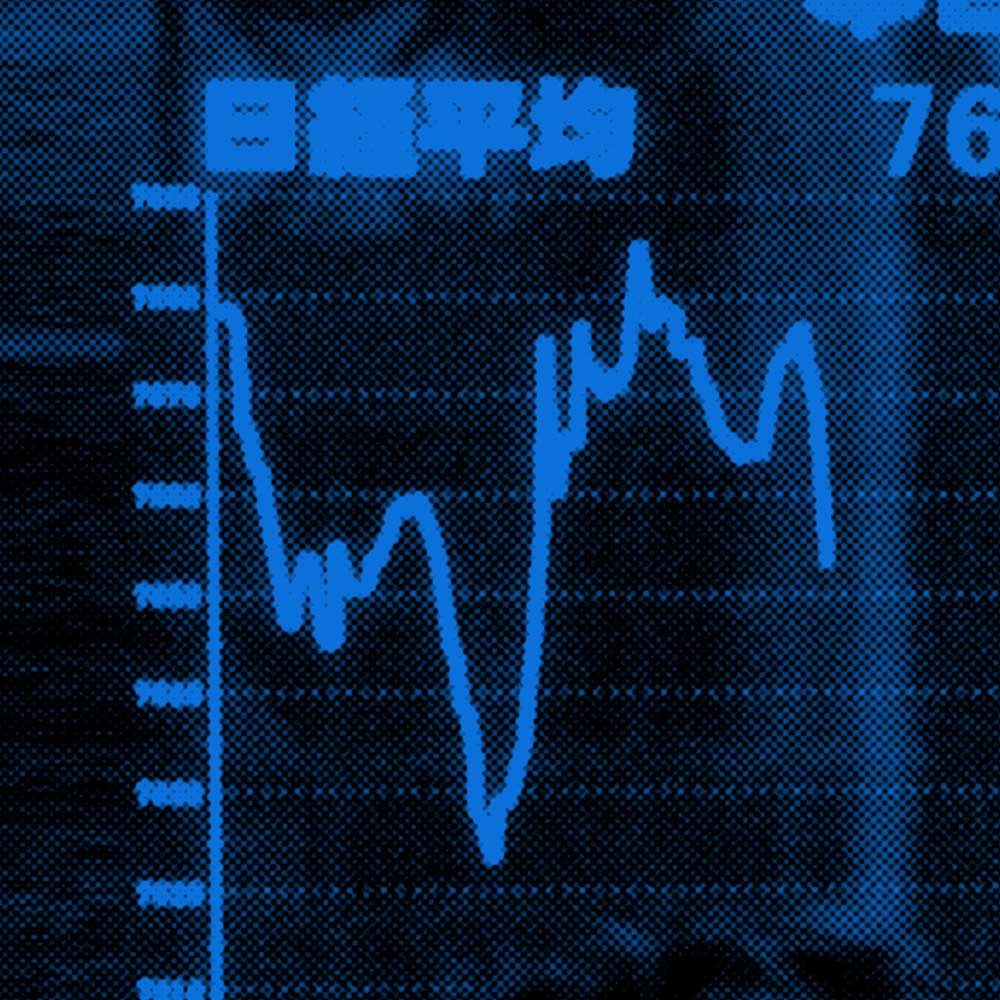

In the end, a stock market meltdown brought about a massive drop in real estate value and asset losses amounting to more than ¥10 trillion, the kind of forfeiture more commonly associated with war.

With its vivacity and razzle-dazzle, Juliana’s is often cited as a symbol of the bubble years. Ironically, at the time of its opening inside a disused storage facility in Minato Ward on May 15, 1991, that bubble had well and truly popped. The Nikkei index on the Tokyo Stock Exchange closed at just below 20,000 — half of its record high 17 months earlier.

Like many regular folk, however, the 4,000 or so revelers at Juliana’s seemed oblivious, swept along as they were by the unique techno-driven atmosphere of the club, where foreign, ponytailed DJs screamed “Everybody, come on!” and a woman’s goal was to get ahold of a juri-sen (a Juliana’s fan made from feathers) and strut her stuff atop three 1.2-meter-high dance platforms while men kept their lower jaws in check as they glanced up furtively from below.

“People turned up in droves night after night, even during the week,” says Hirofumi Takano, 52, who was a member of the disco’s management at the time.

Celebrities and business executives rolled up in their Ferraris, and were escorted past the queuing club-goers up flights of stairs to the VIP rooms that looked down on the dance floor, adding to the “high-flyer” ambience, Takano says.

“They had dedicated waiters who served them champagne and other expensive drinks and received decent tips in return,” he says. “If a bubble had burst you couldn’t hear it at Juliana’s. It was smokin.'”

In a sense, the club created its own micro-bubble, its success spawning a copycat culture of clubs in the capital and other major conurbations such as Nagoya and Osaka. One Roppongi disco convened a “bodi-kon night,” where women who turned up in tight-fitting outfits were let in for ¥100 — significantly less than Juliana’s ¥5,000 entrance fee. Another, in Nagoya, cheekily adapted the idea, letting women in for free if they also wore a G-string.

“Juliana’s success was down to a number of factors that just happened to click,” Takano says. “Most importantly, though, was its foreignness, which was like nothing seen before in Japan. The Japanese, especially in those days, tended to go all jelly-kneed at anything foreign.”

While the asset bubble precipitated calamity in the economy, politics and, ultimately, in society, it prompted a variety of changes in Japanese cultural sensibilities — some connected to that foreign weakness — that would evolve throughout the Heisei years.

Some of the earliest of those changes were inextricably linked to the nature of the bubble economy itself and ostensibly only skin deep.

Discouraged by low interest rates set by the Bank of Japan as the dollar got cheaper, Japanese commercial and manufacturing enterprises looked for new ways to invest their surplus millions, embarking on overseas spending sprees for paintings by the likes of Van Gogh and Picasso, movie companies such as Columbia Pictures, real estate, including New York’s Rockefeller Center, and golf courses from Hawaii to Scotland.

People in the upper echelons of politics and commerce during the bubble years were born in the 1940s, at a time when Japanese people were very poor, says Eiji Oguma, a sociology professor at Keio University’s faculty of policy management, adding that, according to one United Nations report, Japan’s average annual income in 1946 was under $100, placing it slightly above Sri Lanka ($91) and the Philippines ($88), but well behind the U.S. ($1,600) at the time.

“They wanted to acquire such luxury and Western values and aesthetics but, naturally, they were not accustomed to that,” says Oguma, who at the time of the bubble was working on the editorial staff of the left-leaning political magazine Sekai. “Culturally, socially, the Japanese simply weren’t ready — they weren’t accustomed to such luxuriousness and wealth.”

More popular examples of this cultural gorging also existed. Oguma recalls being charged with researching suitable venues for a magazine article about cultural change in the bubble years. One place he found was a lavishly decorated Tokyo restaurant, designed, the owners claimed, by a renowned Italian architect.

“It was very posh, a little kitsch … with classical statues and elaborate tableware,” Oguma says. “However, the food was terrible. Imported Western culture had yet to find any real roots in society at the time. In subsequent years cuisine became a notable exception, and the importation of cuisine culture from abroad contributed to improve cuisine quality in Japan. At that time, however, it was really quite poor.”

His own industry, publishing, experienced a similar situation, Oguma says.

By the late ’80s, the quality of magazines improved rapidly, he says, with many publishing companies making the costly move over to computerized printing, allowing designs to become more sophisticated and visuals to stand out.

Content, however, was left wanting.

“This was partly because of limited information coming in from overseas,” Oguma says. “There was no internet and many music and art critics used stories from publications imported from the West to fill that void. As many were not accustomed to reading English, content suffered.”

Many art galleries and other cultural facilities nationwide — built with huge public injections of cash and under the premise they would attract globally renowned artists and shows, which many didn’t — suffered a similar dilemma.

One that perhaps summed up the times was the Japan Louvre Sculpture Museum in Mie Prefecture, which housed 1,300 sculptures that had been replicated, albeit officially, from those on display at the Louvre in Paris. “The head of the Louvre in Paris attended the opening, but other than that my guess is nobody in Paris would have batted an eyelid,” says Kyoichi Tsuzuki, a journalist, culture critic and photographer who has published several books about the bubble years and their aftermath.

“For local people, however, it was the world’s most famous museum coming to their small town,” Tsuzuki says, adding that such government-led expansion into local areas continued well into the Heisei years, producing ambitious, and often nonviable, projects such as the Huis ten Bosch theme park in Nagasaki. “There’s undoubtedly irony there, but nonetheless it was something solid that was a product of the bubble. Over time, that kind of thing permeated Japan, especially in the provinces.”

Without the bubble that might not have happened, says Tsuzuki, whose 2006 book “Baburu no Shozo” (“Faces of the Bubble”) was a reaction, he says, to the predominantly negative views expressed in other tomes about the era.

“Intellectuals have tended to slam the period, blaming the excesses of the bubble period for all the bad things that have happened in Japan since,” Tsuzuki says. “It’s easy to come to that conclusion. Using money to make things that are beyond absolutely necessary may seem wasteful, but there’s also a kind of dynamism and energy that can result, especially in creative fields.”

This was particularly true in the world of architecture, with some of the most experimental structures being created during those heady years, Tsuzuki says.

“At the time of the bubble there were many young foreign people in creative industries such as art and architecture who came to Japan to try out more ambitious, experimental projects,” he says.

“For some, regulations back home, particularly in countries such as the United Kingdom and France, made such projects all but impossible,” he says. “Japan, however, was a different story. There was plenty of money and, in the provinces at least, space, too — but no cultural regulations. Japan ended up with some incredibly unique structures, designed by people who went on to become some of the globe’s most revered architects.”

Oguma agrees, adding that the world of film was similarly blessed. Money thrown into the industry saw an explosion in more experimental filmmaking, which was supported by a growing number of art-house cinemas, he says.

Perhaps an even more striking revolution of the times could be found in fashion, and not just the kind of fashion found on the dance floors of Juliana’s.

Interestingly, much of the bubble era fashions did conform to a basic premise also found in bodi-kon clothing: All were riddled with rules on how something should be worn, and with what and when, according to Asuka Watanabe, a professor at the life sciences department at Kyoritsu Women’s University.

While designers such as Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo were making an impression on the international stage, even getting their creations on the catwalks of the highly regarded fashions shows of Paris and New York, domestic trends were beginning to show some bubble-inspired developments, says Watanabe, who has authored several books on Japan’s postwar fashion evolution, including 2016’s “Tokyo Fashon Kuronikuru” (“Tokyo Fashion Chronicle”).

“More conventional styles such as nyu-tora (new traditional) and hama-tora (Yokohama traditional) stood in contrast to the more suggestive bodi-kon look, while ‘career fashions’ that developed against the backdrop of the Equal Employment Opportunities Act, and so-called DC Brands were also taking off,” she says.

DC Brand fashions, which mimicked some of the chic designers and were made by labels such as Comme Ca du Mode, Jun and Lopez, were particularly prevalent on department store mannequins and on the pages of fashion magazines such as Non-no, which presented them as “role model” fashions and guided readers on how and when to wear them, Watanabe says.

When it came to the early ’90s, however, Japan’s most populous generation of young adults — the baby boomer juniors — rejected such a “managed” and inflexible approach, going for a more relaxed style that started on the streets of Shibuya — the baby boomer jr. stomping ground — and came to be known as shibu-kaji (Shibuya casual). Interestingly, this was also rule-ridden, with certain must-wear items only being acceptable when made by certain labels. However, the style itself grew on the streets of Shibuya, making it the distant forerunner of the street fashion boom that would consume young trendies for the remainder of the Heisei Era, Watanabe says.

“While the ’80s had been about passing down fashions from the collections to the streets (via the store), the ’90s was the reverse of that,” Watanabe says. “Young people no longer needed ‘professionals’ to tell them how to dress and fashion designers started to refine what was happening out on the street and turn it into expensive high fashion versions.”

Critic Tsuzuki agrees, adding that one way in which culture changed most emphatically in the Heisei years was that the near obsessive use of categories through the bubble years all but disappeared.

“This was the last era of categorizations — in fashion, music,” Tsuzuki says. “Categories used to be important — new wave, techno, gosu-rori (gothic & Lolita), ganguro (tanned faces) and so on. Even art movements, the ‘isms’ in art, such as simulationism and so on. The internet has been a huge influence in this regard, but the idea of one single cultural trend sweeping society came to an end in this era. In that sense, there is a certain nostalgia about those times (up until the early 1990s).”

Former Juliana’s Tokyo official Takano agrees, adding that he occasionally welcomes former regulars at Juliana’s — which closed its doors in 1994, to his karaoke bar in Tokyo’s Nishiazabu neighborhood.

“In 2008, we organized a Juliana’s revival for one night only,” recalls Takano, who continued his career in disco management at Roppongi’s Velfarre — the self-proclaimed largest disco in Asia at one time — before joining music production giant Avex Group. “It was absolutely heaving, mostly with young people who wanted to get a sense of the Juliana’s ambience. There’s talk of doing that again to mark the end of Heisei Era. Just thinking about it sends shivers down my spine.”

Talk of the times

Asshi-kun (アッシー君): A buzzword that became popular in the early 1990s to describe a man who is used for his car and/or ability to transport a woman to places

Messhi-kun (メッシー君): A term that was used around the same time to describe a man who is willing to buy a women fancy meals

Hanakin (花金, “Flower Friday”): The name given to the last working day of the week during the bubble era (金 is the kanji for both Friday and gold)