Boiling Point

Japan’s schools battle to keep kids cool, with or without AC

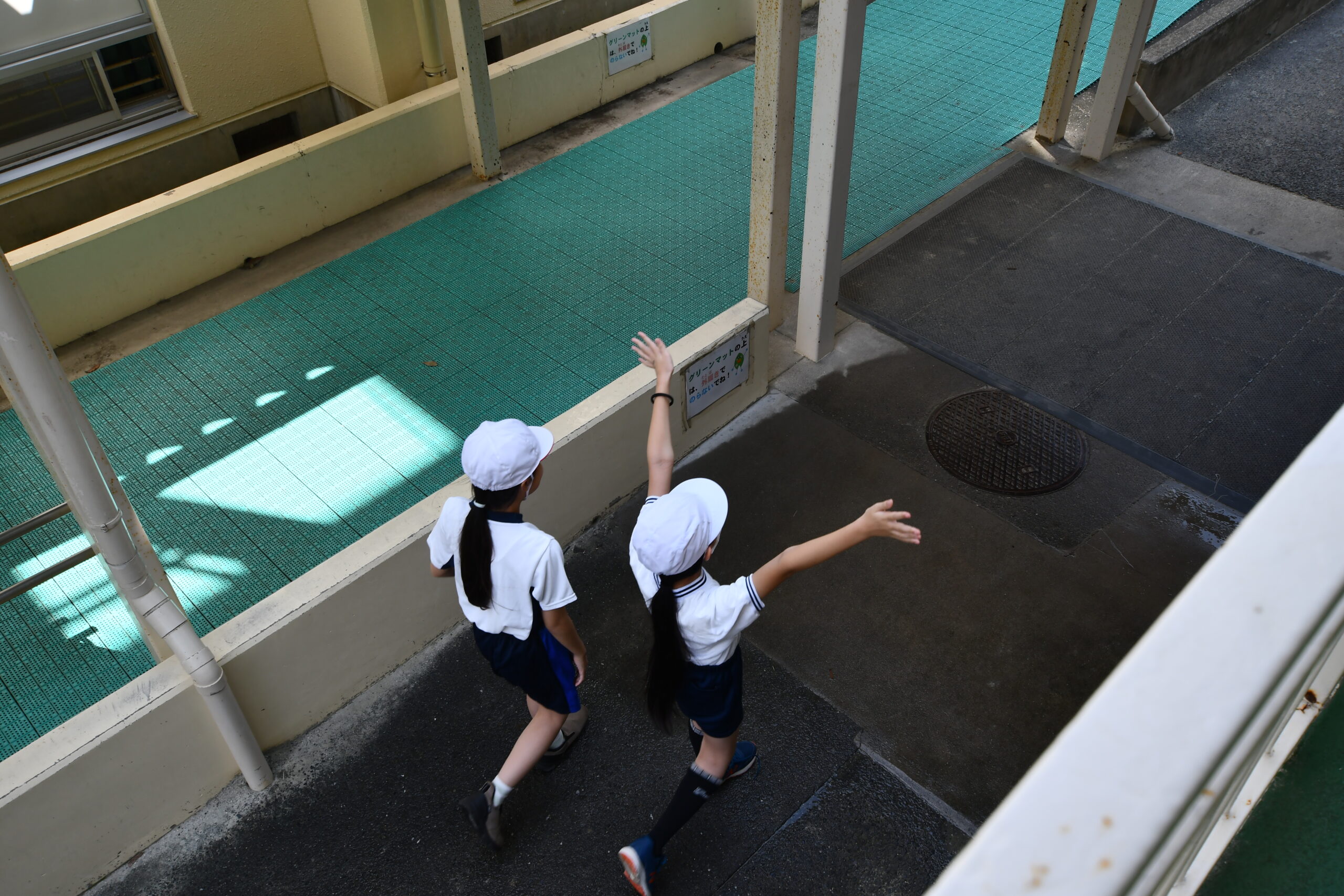

The bell rings to indicate the start of recess, and the students at Hikarigaoka Haru no Kaze Elementary School in Tokyo’s Nerima Ward rush out into the playground — and a fiercely sunny day in early September, the temperature of which is climbing toward a peak of 34.5 degrees Celsius.

Greeting them on the way out is a recently upgraded misting system that offers a degree of respite from the heat. The mist evaporates before it has a chance to get anyone wet.

“It’s cool!” some students shout out.

“Is it rain?” others ask as they raise their arms up to capture the most benefit from the mist.

Such initiatives at schools are becoming more important as temperatures continue to move into unprecedented territory due to climate change.

“I wouldn’t say that air conditioning and water mist make us fully prepared for a changing climate,” assistant principal Hiroo Fujita says. “We have AC but they won’t keep rooms cool enough when the outside temperature is 34 C or higher. We’d like to get outdated units replaced with new ones, ones that aren’t gas-powered. And fix insulation problems, too.”

Schools such as the government-run Haru no Kaze have good reason to improve cooling for students beyond health concerns — several studies point to how extreme heat negatively impacts academic performance.

Indeed, there is a Japanese saying that goes: Those who conquer summer, conquer entrance exams.

On the face of it, Japanese schools are well prepared to handle increasingly extreme heat — 95.7% of regular classrooms at public elementary and junior high schools have air conditioning, according to a 2022 education ministry survey.

But AC only goes so far and its impact is diminished by poorly insulated buildings constructed for a cooler climate — a time when fans and open windows did the job during summer — that is receding in the rear-view mirror. And the encouraging figure masks inconsistent AC coverage within schools and disparities between prefectures, while failing to account for the education that goes on outside the classroom.

Against this backdrop, schools and local governments are racing to plug AC gaps while experimenting with creative, cheaper solutions to keep students’ minds focused on textbooks and not the rising mercury.

Too hot to think

The long-term rate of increase in Japan's average annual temperature is currently estimated to be 1.35 C per 100 years, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency. This year and last, Japan also saw its joint hottest summers on record, and unlike many education systems overseas, Japan’s summer break typically runs from late July to late August, meaning school is open for significant portions of the hottest time of year.

And while the official end of summer is approaching, heat is and will remain a big study distraction for students, with the Meteorological Agency forecasting unseasonably warm temperatures through the end of October. Without proper countermeasures, it’s simply too hot to learn.

Studies show students perform worse on tests when they're hot.

A Harvard study of 44 college students during the summer of 2016 found that those living in buildings without air conditioning performed over 13% worse on both math and memory tests than their air-conditioned classmates.

Meanwhile, a 2018 working paper published by the U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research suggests that for every 1 degree Fahrenheit (0.56 degree Celsius) increase in temperature for the school year in the U.S., student learning drops by 1%.

“The ideal room temperature for cognitive tasks is generally between 21 and 22 C,” says Kikunori Shinohara, a neurologist and a professor at the Suwa University of Science in Nagano Prefecture who was not involved in either study. “When it goes above 25 C, it gets difficult to focus, and when it hits 28 C it can hurt cognitive performance scores.”

Japan has come a long way since 1998, when the nation’s regular classroom AC installation rate at public schools covering grades 1 to 9 stood at 3.7%. But today, many “special classrooms” — which include science labs, computer rooms, home economics rooms and libraries — as well as gymnasiums still lack air conditioning: Only 63.3% and 15.3% have it, respectively.

There are also gaps in air conditioning coverage across the country, with 24 out of 47 prefectures — including Tokyo, Saitama, Chiba, Kanagawa, Shizuoka, Aichi, Hyogo, Hiroshima — having an installation rate of 100% in regular classrooms, while Hokkaido’s was only 16.5% as of 2022.

Schools that are not able to maintain cool temperatures during extreme heat events jeopardize child health and safety, not just test scores.

Children are more vulnerable to heat than adults. The Japan Sport Association says children’s bodies absorb heat much faster because they have a higher body surface area-to-weight ratio, higher metabolic rate and less efficient sweat glands.

“When it goes above 25 C, it gets difficult to focus, and when it hits 28 C it can hurt cognitive performance scores.”

Professor Kikunori Shinohara

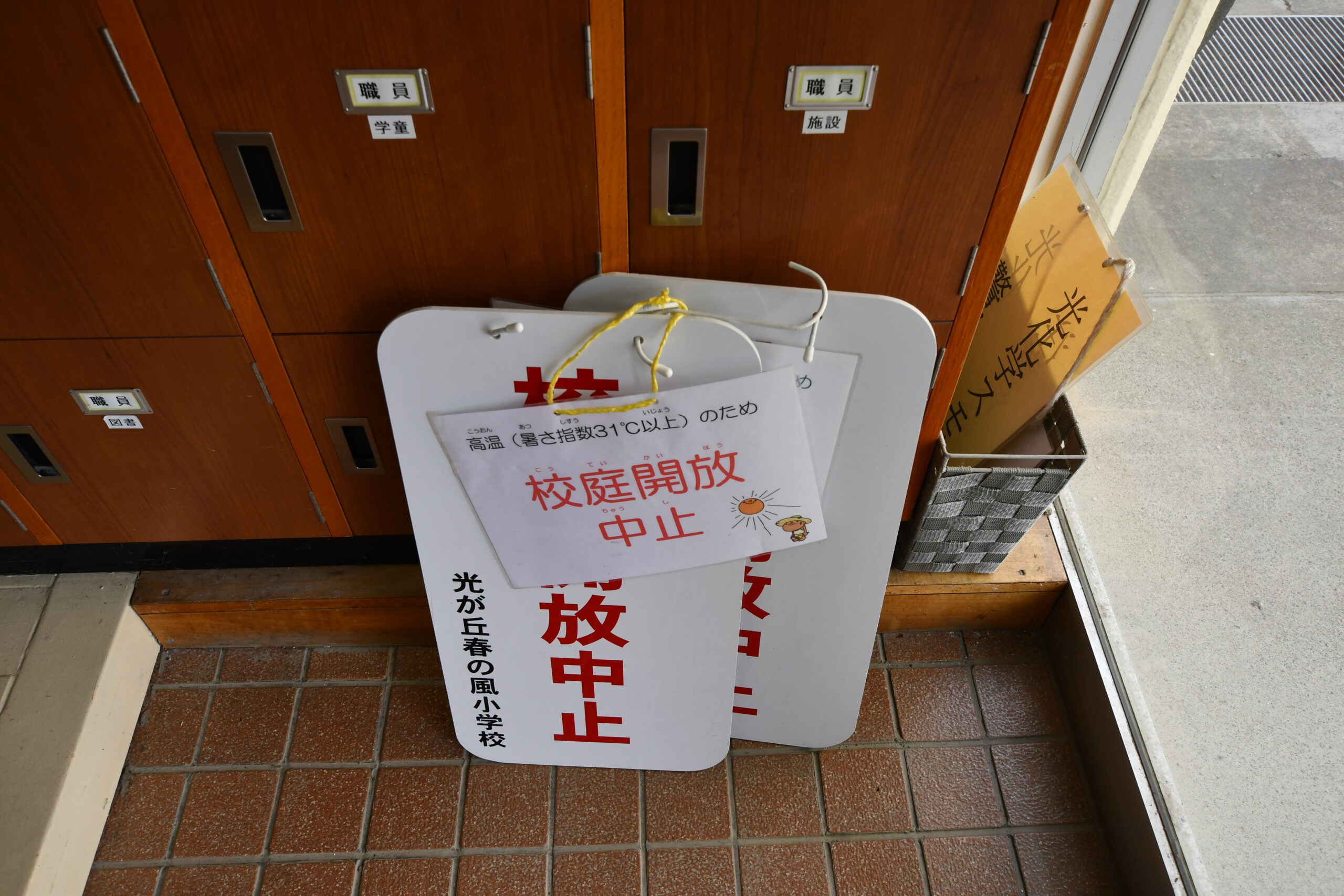

One particular area of concern is physical education classes and school clubs, when students play sports and exercise outdoors. The Environment Ministry says that when the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT) — a measure of heat stress in direct sunlight — hits 31 C, which in Japan generally means 35 C or higher in normal temperature terms, all forms of exercise should be stopped.

Between April 24 and Thursday, 1,585 heatstroke alerts had been issued. The warnings are issued in 58 forecast areas across Japan when the WBGT is predicted to be 33 C or above.

Thousands of cases of heat illness occur annually during P.E. class and school sports club activities, but some happen indoors, too, according to the education ministry.

“It’s best to use AC efficiently in classrooms and reduce the risk of overheating, but if that’s not an option, cooling your neck or other areas rich in blood vessels, scheduling regular breaks and keeping rooms ventilated can help,” Shinohara says.

No magic bullet

July this year was Japan’s hottest July on record. Schools simply weren’t built for this level of heat.

As of 2021, nearly 80% of public elementary and junior high school buildings in Japan had been built more than 25 years earlier, when summers were cooler, according to government data. Many of the older schools are not sufficiently insulated.

Masayuki Mae, an associate professor of architectural environmental engineering at the University of Tokyo, thinks all classrooms should be insulated by 2035 — when most public schools are set to finish their air conditioning upgrades.

“The heat inside classrooms is unbearable — it’s a health danger,” says Mae, explaining that during heat waves students can suffer in temperatures that exceed 30 C even with the AC on because of hot air trapped at ceiling level. “It’s not just a nuisance to students, it’s a barrier to learning.”

Mae says that installing AC requires more than purchasing a unit and plugging it in.

“Many schools have AC units in rooms without proper insulation, solar shading and ventilation. Not only will the room not cool down, this can significantly impair air quality and use extensive amounts of energy, leading to higher electricity bills and carbon dioxide emissions,” he says.

In August 2023, Mae and other insulation advocates turned in a petition with about 27,000 signatures calling on the government to insulate classrooms. Mae has also been sharing his research online to improve awareness of a three-step strategy to address heat in schools: 1) wall and ceiling insulation 2) solar screens for windows and 3) demand-controlled ventilation.

One teacher who works in a public high school in Tokyo points out that it’s not just students who are affected by heat. The English teacher, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, says that in many public schools like hers, teachers have limited control over the thermostat settings because it is controlled by the central office.

“In Tokyo public schools, the AC is set to keep the room temperature at 26 C year round. At our school, teachers can turn the switch on and off, but we can’t adjust the thermostat. You have to have a pretty good reason to get them to alter the settings,” she says.

“Classrooms contain as many as 40 students, so I would turn the AC down another degree or two in the summer if I could — by the afternoon, students lose concentration.”

The education ministry recommends that classroom temperatures be between 18 C and 28 C, depending on the season.

By contrast, a private school teacher in Tokyo says she gets to crank the AC as high as she wants.

The woman, who asked not to be named, says she has been teaching P.E. at the same private high school for 33 years and has never had to worry about being uncomfortable or sweaty in class. She finds it hard to believe some schools don’t have adequate cooling in 2024.

“We’re not a rich school, but overheated classrooms have never been a problem,” she says. “I think the school charges extra fees for air conditioning, but when a unit is broken it gets fixed right away. The students might be asked to move to another room, but we make sure they’re learning in cool, safe temperatures.”

Seeking refuge

School facilities are just one part of the education equation.

In addition to sports clubs and P.E. classes, walking to school and back home with the sun beating down on them can also put children at higher risk of dehydration and heat-related illness.

Despite the dangers, school is a place of refuge for some students, particularly those that come from poorer backgrounds.

In Japan, the summer school break usually lasts for about 40 days. That period can be especially hard for low-income families, who have to worry about feeding children and keeping them cool when school is out.

Approximately 1 in 9 children in Japan lives in relative poverty, according to the welfare ministry.

A recent survey conducted by nonprofit organization Kidsdoor found that 60% of low-income families with children want summer vacations to be shortened or eliminated because of the additional financial strain.

“I wouldn’t say that air conditioning and water mist make us fully prepared for a changing climate.”

Hikarigaoka Haru no Kaze Elementary School assistant principal Hiroo Fujita

Of the 1,821 respondents from families in need — 90% of them single mothers — 61% said high energy costs make them reluctant to use air conditioning.

“The heat has been so intense this summer that even low-income parents have said it’s hard for them to tell their kids not to use AC at home. We found that many junior high school and high school students study at public libraries or shopping mall food courts,” Kidsdoor public relations officer Kyoko Meguri says.

“Children from disadvantaged backgrounds don’t have access to a study desk at home. Poor academic performance is a concern for parents,” she says, adding that the nonprofit offers learning support programs for children and teenagers.

A single mother in Tokyo relying on public assistance while raising two neurodiverse children says that when her boys — now 13 and 15 — were younger, she had to skip work and take them to the jidōkan children’s center, which she calls her “safe haven,” to escape from the heat in the summertime, but now she has them go alone.

“When school’s closed I tell them to find a cool place that doesn’t cost money to do homework. We have AC at home but I’m trying not to use it because of the already high electric bills,” she says.

“My kids are always tired and have no motivation to study. I don’t know if it’s the heat or their mental health condition,” she says. “They’re always complaining, saying it’s hot at home and hot at school.”

Getting creative

Adapting to the reality of hotter summers comes at a price.

The cost of installing a new AC unit is ¥2.2 million (about $15,600) per classroom, according to the education ministry.

The central government covers one-third of the installation costs through a subsidy to improve school facilities, with this being increased to half for gymnasiums through March 2026, but with tight budgets, education providers are having to think smarter to make less go further.

Saitama Prefecture’s Kumagaya, dubbed Japan’s hottest city, and Fukuoka Prefecture’s Chikugo are among the municipalities that have taken to giving out parasols to elementary school students, while all elementary schools in the Hyogo Prefecture town of Inami have had a parasol rental system since 2020.

Nagoya-based umbrella manufacturer Ogawa says sales of sun protective umbrellas for children have almost doubled this year, with stock running out at one point. The majority of customers are parents with school-age children, but according to Yuki Yato, a product planner at Ogawa, they’re also popular gifts for grandchildren.

“We’ve created children’s sun umbrellas because extreme heat is putting children’s health at risk and some of our employees were worried about their own children walking to school on sizzling hot pavement every day, and we wanted to do something,” Yato says.

Having their own patch of shade following them everywhere may make a heat wave far more bearable, but not all schools allow children to carry sunblock umbrellas due to safety and injury concerns.

At the same time, some schools are investing in infrastructure to withstand extreme heat, while others with less wiggle room to adjust expenditures are coming up with low-tech, low-cost cooling solutions.

In Nerima Ward, about 46,000 children are enrolled in public elementary and junior high schools, including Haru no Kaze, that are implementing heat resilience measures.

This year, the ward spent ¥200 million to set up mist spray systems and canopy tents at all of its 98 public elementary and junior high schools. According to a ward official, the measures were taken after heat caused record-high rates of health emergencies last year.

Haru no Kaze saw its old, worn-out misting system — which connects to a water faucet and can be hung from a roofline — replaced with a brand new one. The school first requested the system six years ago, when the ward conducted a survey to assess cooling needs across schools.

“We turn the water on during recess and lunch breaks. We’ll use it while it’s hot, probably through October. I don’t know how effective it is as heatstroke prevention, but children are kept entertained. They cool off before going back to their classrooms,” principal Tsutomu Naiki says.

Haru no Kaze is also wrapping up the installation of eight new AC units in its 40-year-old gymnasium, bringing air conditioning to the building for the first time.

There are cheaper ways to help students deal with heat, like ensuring a regular supply of drinking water and adopting school uniforms better suited to hot weather, such as polo shirts, shorts and P.E. attire. In a growing number of schools, students are allowed to temporarily ditch their box-like randoseru backpacks and use lightweight, breathable bags instead.

Elsewhere, schools are turning to nature to help them conserve energy, creating “green curtains” by growing climbing plants, such as bitter gourd and morning glory, to shade their windows and cover walls.

Green curtains lower indoor temperatures and reduce the need for air conditioning. The curtains have a shielding effect that blocks about 80% of the sun's heat energy, compared with 55% for solar control glass and 50% to 60% for sudare bamboo blinds, according to the Environment Ministry.

Every year since 2014, Tokyo’s Sumida Ward has been organizing the Green Curtain Contest, an initiative aimed at recognizing and rewarding schools, businesses and individuals that are dedicated to promoting sustainable cooling.

Such interventions underline the fact that schools will need to adopt a variety of approaches to keep students cool.

“We’re a public school so generally our rules are made by Nerima Ward, based on the guidelines set by the national and local governments,” Haru no Kaze’s Fujita says. “But schools are having to get creative to protect children from heatstroke, using their limited financial resources to do what they can.”